Activating Learning Within Digital Spaces

H Carroll; S Driessens; and P Maher

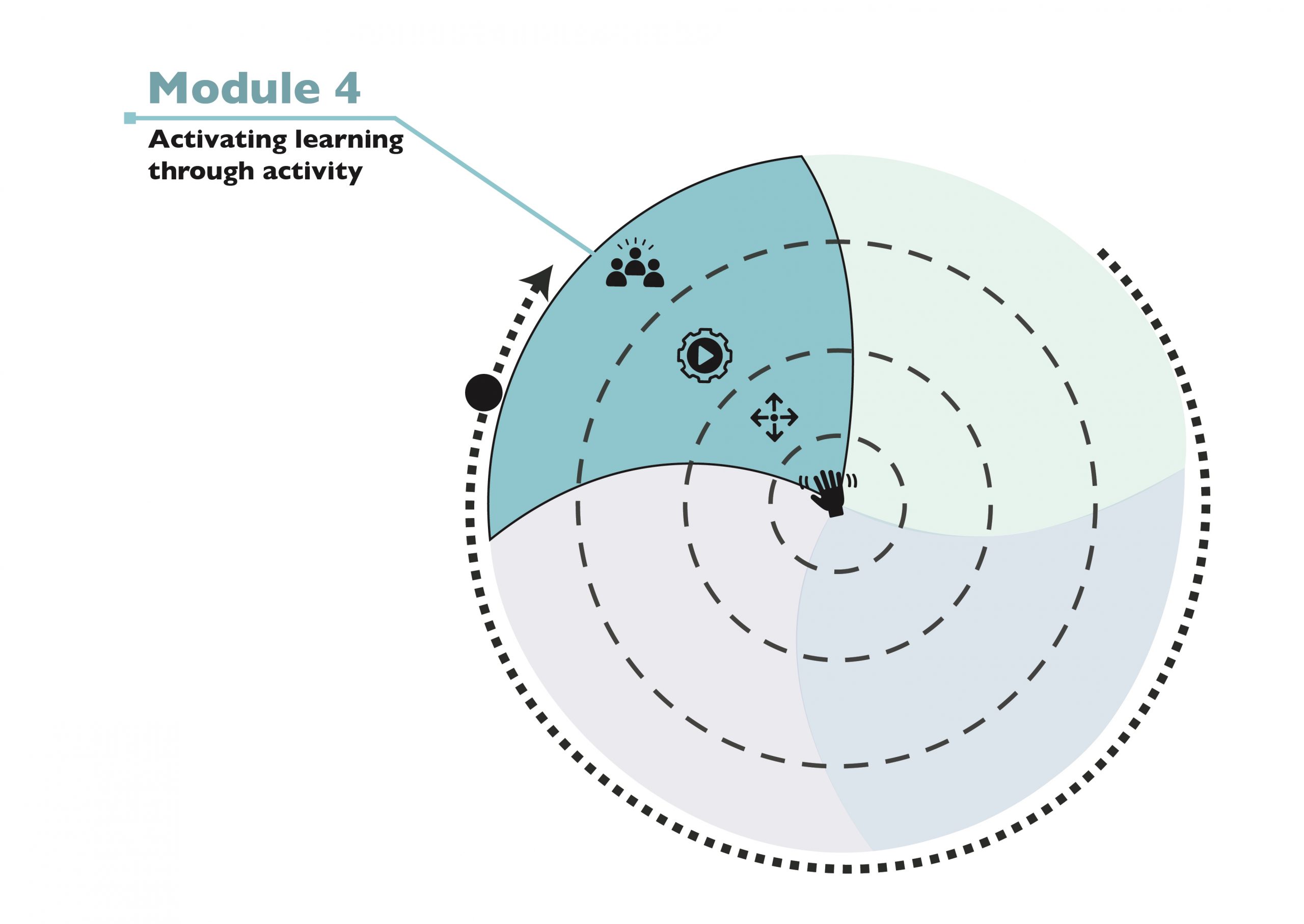

In this module, you will explore several ‘toolkits’ that demonstrate course themes in action, and analyze these toolkits and their contents to see which activities fit your own teaching.

|

Key Takeaways for this week Create a course structure that effectively activates learning within a digital space. Design and implement strategies that activate learning in ways that support learner agency for pace, place and mode of learning.

|

This module has 4 parts:

![]()

Introduction

Identifying the ‘location’ of this module within the course level learning will spark the introduction of module theories being considered(inquiry based engagement, active learning and social connectivity). Course participants will explore several ‘toolkits’ that demonstrate these themes in action, and will apply these concepts to their own work.

![]()

Expansion

You will be challenged to analyze these toolkits and their contents to see which activities fit your own teaching.

![]() Refinement/Application

Refinement/Application

Once more familiar with the toolkits you will be asked to take an example and apply it to your course/lesson design.

![]() Reflective Practice

Reflective Practice

We will ask you to return to your current and past experiences in order to protect/incorporate important practices already happening!

Introduction

Introduction

In the previous modules, you have explored course design, enhancing your course design through interaction, and resourcing learning effectively. In this final module, we are going to explore the importance of activating learning including different strategies and activities you can use to move learners from passive to active participants. We will also discuss the importance of learner agency in relation to active learning and course design more broadly.

![]() Before we dive in, take a few minutes to summarize what you have learned so far; just a few sentences to summarize each module. Then, pose one or two questions about the final module keeping in mind the theme of active or activating learning. When you are ready, watch the introductory video that maps out the final module.

Before we dive in, take a few minutes to summarize what you have learned so far; just a few sentences to summarize each module. Then, pose one or two questions about the final module keeping in mind the theme of active or activating learning. When you are ready, watch the introductory video that maps out the final module.

| Download Video file | Download transcripts | Download slides |

Active Learning: A Primer

Where Have You Been?

When thinking about designing and creating quality, technology-enabled learner experiences, a key consideration is how to move beyond passive learning to incorporate active learning. Part of this process involves a shift in how we think about learning and learners, from passive recipients of knowledge to active co-constructors of knowledge in relation with their instructor and peers. Put differently, active learning supports Freire’s (1970) belief that “the teacher-of-the-students and the students-of-the-teacher cease to exist and a new term emerges: teacher-student with students-teachers” (Freire, 1970). Within this context, instructors become learners as you consider your own knowledge, experiences, areas of strength, and opportunities for growth.

- What are my experiences with learning as a learner and teacher?

- What do I believe about how learners learn best?

- What do I already know about active learning?

- What piques my interest in active learning?

- What makes me uneasy about active learning?

Where Are You Going?

There are many factors to consider when planning and implementing active learning strategies. The final module in this course will help support your growth by offering practical strategies that you can implement into your course design. Before diving into the content, remember that the goal is to meet you where you are in your own learning journey, while similarly extending this mindset to your course design and current/future learners.

This module will help you to:

- Define active learning including its underlying assumptions and principles;

- Compare and contrast active learning with experiential learning and activating prior learning/knowledge;

- Provide examples of active learning strategies;

- Invite you to consider your strengths and areas for growth in relation to bringing active learning into your course design; and

- Offer opportunities for you to apply your learning to your course design.

What is Active Learning?

Active learning involves actively engaging learners by “involving [them] in doing things and thinking about the things they are doing” (Bonwell & Eison, 1991). For example, you might involve learners through online discussions, role playing, or case studies. The key factor to consider when designing active learning strategies is to ensure that learners have greater responsibility for their learning, thinking, and doing, but that you are still providing support and guidance.

“Active learning strategies are classroom techniques that engage students with the subject they’re studying by discussing it, writing about it, applying it in some meaningful context, or otherwise working it into the fabric of their own experience and prior knowledge. They become active creators of knowledge rather than passive recipients of information” (Worley, 2007, p. 450).

Underlying Assumptions of Active Learning

Based on a review of the literature, active learning:

- Involves dialogue with the self, as learners reflect on their learning, thinking, and doing; and dialogue with others, as learners converse (orally or in writing) with peers, as well as you (Fink, 2010).

- Looks at learning holistically by focusing on experience (e.g., doing, observing), reflective dialogue (with self or others), and information and ideas found within the content (Fink, 2003).

- Is learner-centred emphasizing exploration, growth, and development, rather than instructor-centred, which emphasizes knowledge transmission (Austin & Mescia, 2004).

- Focuses on interaction as learners encounter and engage with new information and ideas, perspectives, viewpoints, etc. (Columbia Center for Teaching and Learning, n.d.).

- Incorporates learning by doing whereby learners dive deeper into course content through active involvement (Bolliger & Des Armier, 2013).

- Involves drawing upon the learner’s prior knowledge to scaffold new information and ideas (Kinsella, Mahon, & Lillis, 2017).

- Allows learners to move beyond surface level learning by diving deeper into course content through application and knowledge transfer (Queens University, n.d).

Principles of Active Learning

‘Active Learning Overview‘ by ‘MIT OpenCourseWare‘ is Creative Commons BY-NC-SA licensed

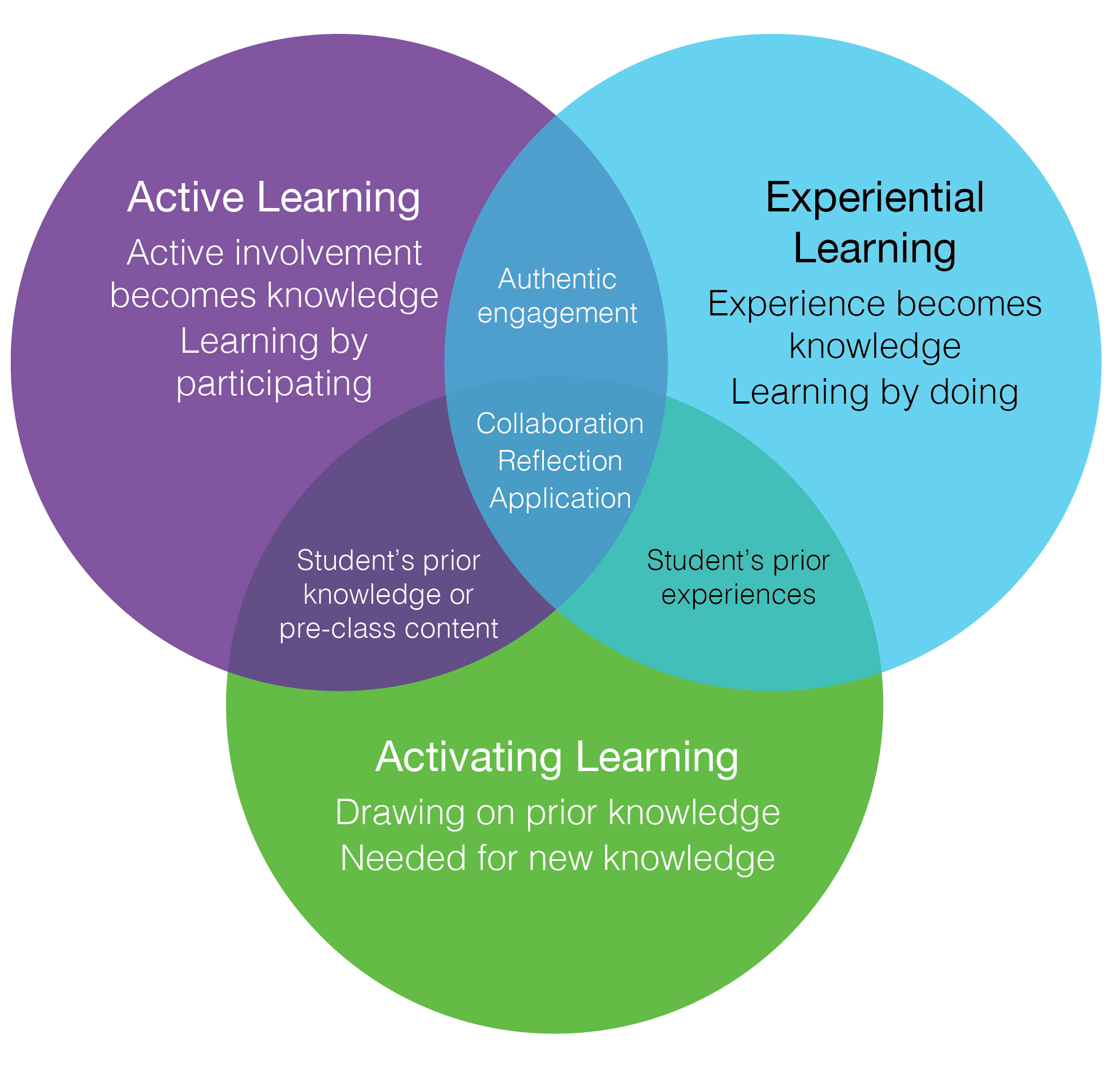

As you learned previously, constructivist learning emphasizes knowledge construction, including collaborative construction or co-construction of knowledge. Active learning applies principles of constructivism (e.g., dialogue, knowledge construction, diverse ways of knowing and thinking, learning is contextual, learning takes time) to help learners thoughtfully engage with course material, each other, and their own thinking. Active learning has roots in experiential learning, or learning by doing, whereby instructors give learners “something to do, not something to learn; and the doing is of such a nature as to demand thinking; learning naturally results” (Dewey, 1916). Active learning involves elements of, but is not necessarily synonymous with, experiential learning. Relatedly, activating learning by drawing on the learner’s prior knowledge, is equally important. The figure below compares and contrasts these three interrelated concepts.

When thinking about active learning, keep in mind that it can take a variety of forms and can occur individually, in small groups, or in large groups. Active learning shifts the onus of responsibility for learning from the instructor to the learner, but guidance and modelling are critical structures for active learning to thrive. Active learning strategies can be woven into your course design, including those strategies that tend to be more passive for learners such as lectures. The next section provides some examples of active learning strategies for your consideration.

Evidence that Active Learning Works

Active learning is a proven learning strategy that supports learner engagement as they dive deeper into course content and apply their learning. For example, active learning has been linked to:

- Increased understanding and knowledge of course material, and a more enjoyable learner experience (Braxton et al., 2008)

- Broadened scope of application (Waldrop, 2015)

- Enhanced resilience, problem-solving, and ability to overcome challenges (Lopatto, 2007)

- Improved test scores and overall passing rates (Mello & Less, 2013)

‘A Jigsaw Activity as a Capstone in a Mineralogy Classroom – Part 1 of 3’ by ‘University of British Columbia Faculty of Science’ is licensed under a CC Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.’

For us, active learning isn’t a question of what or why, it’s a question of how. How you use active learning in your course is up to you and needs to make sense in the context of your course design.

Now let’s get back to your design blueprint from Module 1. Refine the blueprint by considering how to integrate active learning either for an individual learner or a small or large group of learners.

Expansion

Expansion

What is Learner Agency and How Does it Relate to Active Learning?

According to Stommel (2020), designing quality technology-enabled learning experiences requires you to build a course and a classroom. The best learning experiences are those grounded in learner agency. You should build a course by considering who your learners are – where they come from, what they know, what they ought to know – and build pathways that empower them to own their learning journeys.

There is no universally accepted definition of learner agency. However, a review of the research literature suggests some common elements:

- A belief in learner self-efficacy on both the part of the instructor and the learner (Davis Poon, 2018);

- Choice, voice, and ownership within, throughout, and over the learning process (Driessens, Scarlett, & Parr, 2019);

- Meaningful connections between what is being learned and the learner’s lived experiences (Margolis, 2016); and

- Learners as active agents who have a desire to deeply engage with the learning process (O’Rourke & Addison, 2017).

This is not necessarily an exhaustive list, but it does at least highlight important elements that provide insight into how you can use active learning strategies to cultivate learner agency within your course design.

Grounding your course design in learner agency also demands that you recognize the inherent worth and value of learners; you must view learners as fully capable of engaging in real social change and enacting diverse destinies. In order to make this a reality, you need to wholeheartedly trust them as competent and capable learners.

Cultivating Learner Agency Online

According to Morris (n.d.), when it comes to online course design we need to “begin playfully outside the borders of how we’ve always taught and how we relate to the machines that can help us teach.” Pause for a moment to really reflect on what you believe learner agency looks, sounds, and feels like, and how that translates into a digital space. We offer a few suggestions below to get you started, but encourage you to get curious about your own understanding of learner agency in relation to yourself as instructor, your course, and your learners.

- Whether teaching fully synchronous or asynchronous, onsite, or hybrid, you need to put the work of your learners, including their lived experiences, interests, and passions, at the centre of your course. Allow their voices to be heard more than yours. For example, invite learners to create or co-create lecture videos so that they learn from each other, while simultaneously building community.

- Consider allowing your learners to ‘choose their own adventure’ when it comes to assessment. Ask yourself how you can provide multiple modes of representation to meet learners where they are, rather than where you expect them to be. For example, allow learners to choose how they represent their learning (e.g., through an essay – traditional, video, or photo -, podcast, tweets, etc.) or, better yet, plan open-ended projects that have real-world applications.

- Get curious about what you use for evaluating assignments. If you typically use traditional rubrics, consider adopting a single-point rubric. Push yourself to take this one step further by inviting learners to co-construct evaluation criteria by asking what they feel is most important and/or most representative of their learning.

- Critically reflect on your beliefs, assumptions, and practices about teaching, learning, and learners. How do you view your authority as an instructor? Remember that “active learning puts [learners] at the center of the learning space” (Stommel, 2020). How will you lean into active learning as a fully engaged learner and participant in your course?

- Get intentional about the technology you use. Remember, use the technology, don’t let it use you! Quality technology-enabled learning provides sets of tools that you can use, but they do not, and should not, dictate how you teach. Your course design needs to be grounded in pedagogically-sound principles and practices that shift learners from passive to active participants in your course. Whatever tool you select from your toolkit needs to be intentional.

Application

Application

Pause & Ponder

Pause for a moment to revisit your learning design blueprint. Put yourself in the position of a learner and ask:

- Would you feel trusted, valued, empowered?

- Would you feel like you could succeed?

Make any necessary adjustments or modifications to your design based on your answers.

Active learning can be used to introduce new topics, ideas or information (both online and face-to-face); analyze or apply course concepts and content; facilitate effective peer feedback; and apply learning. When considering which active learning strategies you will utilize, the following questions can help to facilitate your decision-making process:

| What are your time constraints? | How much time you have to focus on building and implementing active learning strategies ought to be considered during your planning process. However, even if you are pressed for time, brief active learning strategies can still help support student engagement. |

| What is your class size? | Active learning can occur in both large and small classes, you will just need to adjust your format. In a smaller class, you might be able to utilize a think-pair-share, whereas in a larger class, you may find yourself weaving in a jigsaw activity. |

| What is your comfort level? | Your own experiences with active learning, as both a learner and an educator, are important to consider. If you are new to active learning, start small and consider adding a small, low-risk active learning activity to break up the course delivery or get curious about what students learned in class that day. |

| What is your course modality? | Active learning is valuable for face-to-face, online, and hybrid course delivery. What activity you choose needs to fit both the context of your course, as well as the context of your course delivery. For a face-to-face course, students may brainstorm by creating a graffiti wall. The same activity can be utilized online (both asynchronous and synchronous) by creating a shared, interactive document for students to brainstorm such as a Jamboard or virtual whiteboard. |

We encourage you to start small in your planning and think about one active learning strategy you may want to include in your course design. As your experience and confidence builds, then so, too, can your course design.

Reflective Practice

Reflective Practice

Now that you have reviewed the content about active learning, we invite you to reflect on what you have experienced as a learner and what you have used as an instructor. Using the following reflection questions as gentle prompts, start a conversation with a peer/colleague:

-

- What active learning strategies have you experienced as a learner?

-

- What active learning strategies have you used as an instructor?

Next: Consider what areas of your course could most benefit from active learning. We invite you to get curious about one or two new activities and apply to your course design. In the spirit of collaboration, we invite you to share with the community what active strategies you hope to use and why using this collaborative Jamboard.

Finally: Twitter chats are a fun and engaging way to get intentional about social media and tech-enabled learning. We invite you to get curious about learner agency and what it means to you within the context of your course. Share your thoughts, perspectives, and experiences by using the hashtag #LearnerAgency. Please tag the creators of this resource in your tweets/retweets (@NU_TeachingHub and @LUteaching).

In closing

First off, let’s take a moment to celebrate how far you have come! From Module 1 all the way until now, you have brainstormed, drafted, edited, revised, and polished your design blueprint. Congratulations!

Remember the importance of relationality in learning – the more you put into your design and the community with whom you shared this experience, the more you will get out of the course. Moreover, seeing the work of others positively contributes to teaching excellence and creates opportunities for you to not only lean on your peers, but also adapt or modify their practices to strengthen your own. It is for this reason we hope you had a ‘learning buddy’ with you in this course.

“Success is a journey, not a destination. The doing is often more important than the outcome.” ~ Arthur Ashe

In closing, we would like to reiterate that course design is iterative; you’ll move back and forth between brainstorming, drafting, editing, back to brainstorming, and so on. Congratulations again on your journey!

Module References

Austin, D., & Mescia, N.D. (2004). Strategies to incorporate active learning into online teaching. Retrieved from https://ap.uci.edu/wp-content/uploads/102417-Austin-and-Mescia-STRATEGIES-TO-INCORPORATE-ACTIVE-LEARNING-INTO-ONLINE-TEACHING.pdf

Bolliger, D.U., & Des Armier, D. J. (2013). Active learning in the online environment: The integration of student-generated audio files. Active Learning in Higher Education, 14(3), 201-211. https://https://doi.org/10.1177/1469787413498032

Bonwell, C.C., & Eison, J.A. (1991). Active learning: Creating excitement in the classroom. Association for the Study of Higher Education. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED336049.pdf

Braxton, J. M., Jones, W. A., Hirschy, A. S., & Hartley III, H. V. (2008). The role of active learning in college student persistence. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 2008(115), 71-83. https://doi.org/10.1002/tl.326

Columbia Center for Teaching & Learning. (n.d.). Active learning for your online classroom: Five strategies using Zoom. https://ctl.columbia.edu/resources-and-technology/teaching-with-technology/teaching-online/active-learning/

Davis-Poon, J. (2018, September 11). Part 1: What do you mean when you say “student agency”? https://education-reimagined.org/what-do-you-mean-when-you-say-student-agency/

Dewey, J. (1916). Democracy and education. Courier Corporation.

Driessens, S., & Parr, M. Cultivating critical imaginations in ourselves, others, and the world. CAP Journal: The Canadian Resource for School-Based Leadership, Spring Issue. https://cdnprincipals.com/cultivating-critical-literacy-imaginations-in-our-selves-others-and-the-world/

Fink, L.D. (2003). A self-directed guide to designing courses for significant learning. https://www.deefinkandassociates.com/GuidetoCourseDesignAug05.pdf

Fink, L.D. (2010). Active learning. https://commons.trincoll.edu/ctl/files/2013/08/Week-3-Active-Learning.pdf

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed. Continuum.

Kinsella, G.K., Mahon, C., & Lillis, S. (2017). Using pre-lecture activities to enhance learner engagement in a large group setting. Active Learning in Higher Education, 18(3), 231-242. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469787417715205

Lopatto, D. (2007). Undergraduate research experiences support science career decisions and active learning. Life Sciences Education, 6(4), 297-306. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.07-06-0039

Margolis, A. (2016, March 23). What is student agency? https://inspiredteaching.org/what-is-student-agency/

Mello, D., & Less, C. (2013). Effectiveness of active learning in the arts and sciences. Humanities Department Faculty Publications & Research. 45. https://scholarsarchive.jwu.edu/humanities_fac/45

Morris, S. M. (n.d.). The failure of an online program. https://pb.openlcc.net/urgencyofteachers/chapter/the-failure-of-an-online-program/

O’Rourke, M., & Addison, P. (2017). What is student agency? https://www.edpartnerships.edu.au/file/387/I/What_is_Student_Agency.pdf

Queens University. (n.d.). Active learning. https://www.queensu.ca/teachingandlearning/modules/active/index.html

Stommel, J. (2020, May 19). How to build an online learning community: 6 theses. https://www.jessestommel.com/how-to-build-an-online-learning-community-6-theses/

Waldrop, M.M. (2015). Why are we teaching science wrong, and how to make it right. Nature, 523, 272-274. https://doi.org/10.1038/523272a

Worley, R. B. (2007). Active learning strategies, part 1. Business Communication Quarterly, 70 (4), 450-451. https://doi.org/10.1177/1080569907308961

Go beyond the Module with these Readings and Resources

- Centre for Teaching Excellence, The University of Waterloo. (2021). Active learning activities. https://uwaterloo.ca/centre-for-teaching-excellence/teaching-resources/teaching-tips/developing-assignments/assignment-design/active-learning-activities

- Centre for Teaching & Learning, Columbia. (n.d). Active learning for your online classroom: Five strategies using zoom. Active Learning for your Online Classroom: Five Strategies using Zoom (columbia.edu)

- Petersen, C.I, & Gorman, K.S. (2014). Strategies to address common challenges when teaching in an active learning classroom. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 2014(137), 63-70. https://doi.org/10.1002/TL.20086

- Wahyuningsih,D. (2016). Active learning through discussion in e-learning. International Journal of Active Learning, 1 (1), 1-4. https://www.learntechlib.org/p/208699/