12 “Ugly” Fandom

Up to this point, we have already encountered numerous instances of reminders (or warnings) about the less savoury aspects of fandom and participatory culture. Perhaps the most obvious linkage is the week on anti-fandom:

Scholarship on anti-fandom often focuses on anti-fans’ resistance to media texts and celebrities they find boring, banal, or excessive, heralding their nark, cleverness, and opposition to the powers that be. But alongside these instances of anti-fandom run darker, more ominous instances of dislike and hate. (Willson Holladay and Click, 2019, p. 164)

We end this section of the book by focusing upon these darker, more ominous instances of active audiences. The idea that we can analyze audiences and “ugly fandom” is a direct rejoinder to the first wave of fandom studies’ idea that “fandom is beautiful.” Fandom can also be ugly, a fact that is easily evident from “the proliferation of social media platforms [that] provides a figurative bullhorn for fans to celebrate and commemorate, or criticise and commiserate” (Proctor, 2017, p. 1123). Social networks are often anti-social networks and the criticism can become condemnatory, especially when it “mushrooms into harassment, bullying and other types of toxic fan practices” (Proctor, 2017, p. 1123). So what do we mean when we use the term “toxic fandom“?

When theorizing toxic fan practices, we more often than not focus on overt expressions of misogyny, racism, homophobia, and xenophobia (or some combination thereof) within fan communities. ‘Toxicity’ in this context is thus commonly, albeit problematically, positioned as an invasive and poisonous force within otherwise progressive fan cultures and communities, or perhaps simply an exposure of these always already present biases. (Scott, 2018, p. 143)

Toxicity isn’t unique to participatory culture or fandom. It is, rather, part of everyday life. “Fan cultures, like all communities, are based on the necessity of Othering and distinction. Aggression serves instrumental functions within a group byinf helping to enforce norms, build cohesion, and defend against outsiders” (Proctor, 2017, p. 1127). Similarly, toxicity isn’t a new phenomenon but “discourses labeled as toxic are a relatively recent emergence resulting from the particular circumstances of our time” (Proctor and Kies, 2018, p. 135). Toxic masculinity is perhaps the most recognizable construct, but female and queer and progressive toxicity also describe practices and performances rooted in debate and conflict. Thus toxic fandom is too easy and too broad of a label to apply to entire groups of fans, not all of whom engage in toxic fan practices. Indeed, one can even make the distinction between good and bad toxicity. As Hills notes, “toxic fan practices can be seen as ‘good’ by those carrying them out” (2018, p. 114). Activists who meet enemy combatants at their own level see the reactionary strategies of the Other as bad, but their own reactions as progressive and necessarily good. Yet this results in “a banal equation of right-wing and left-wing toxicity, where all sides are just as bad as one another and no political self-justification can survive toxic mirroring” (Hills, 2018, pp. 115-6).

Others make the association between anti-fandom and toxic fandom clear, pointing out how, “as anti-fandom has become increasingly intertwined with factors such as gender and race … often negative stereotypes of certain types of fans have emerged and been circulated to denigrate and dismiss those with opposing viewpoints or from specific demographic groups” (Williams and Bennett, 2022, p. 1037). They proceed to state how, “alongside the broadening of understandings of anti-fandom, the concept of “toxic fandom” has been used to map and understand increasingly hostile responses to media franchises” (Williams and Bennet, 2022, p. 1037). Stanfill goes even further, articulating the need for a concept such as ‘reactionary fandom.’ He argues that “‘anti-fandom’ first named by Gray indicates only opposition and does not categorize the subject matter at hand; reactionary fandoms may be either anti-fandoms of progressive causes or fandoms of reactionary causes” and suggests that “while reactionary fandoms, as sites of domination, are inherently toxic, nonreactionary fandoms can also be toxic” (Stanfill, 2020, p. 125). As clear as mud, we might suggest that “indeterminacy thus haunts any discussion of toxic fan practices: where are the lines to be drawn around ‘fandom’, and equally where should we locate conceptual boundaries around the ‘toxic’?” (Hills, 2018, p. 107).

In an explicit link to both public relations and fandom and consumer fandom, Rick and Morty fans demonstrated their ‘extremism’ in October 2017 as they directed their public sentiment toward McDonalds (demanding the return of a long discontinued sauce) and then protested when the P.R. stunt was poorly organized and public demand for the sauce was radically underestimated.

The media widely reported on the incident in hyperbolic terms, with a few isolated incidents of so-called “rabid” fans chanting, pushing, and standing on counters broadly classifed as “riots.” … The events have subsequently been held up by journalists and fans as one (if not the) prime example of how fan culture has grown increasingly “entitled” and “toxic” over the past several years.[1] (Scott, 2021, p. 59)

https://twitter.com/Chauncey_Boy/status/916793648850755584?ref_src=twsrc^tfw|twcamp^tweetembed|twterm^916793648850755584|twgr^60cbb0724e83f00d4fa71ad9c09f7a697d7b61ad|twcon^s1_c10&ref_url=https://www.polygon.com/2017/10/9/16447204/rick-and-morty-szechuan-sauce-justin-roiland-dan-harmon

Using this example, Scott reminded reader that, “when confronting reactionary instances of ‘toxic fandom,’ it is vital to consider what they are reacting to, as well as what expectations have been violated” (2021, p. 68). The Rick and Morty example is a problematic one because so much of it is tied up in toxic geek masculinity, rooted in a co-creator’s love of the sauce, a co-creator who was subsequently fired due to allegations surrounding his own toxic behaviour.[2]

toxic geek masculinity…

All in all, we might very well be operating in conditions of “digital dissensus,” the current period in politics where it seems conditions of civil discussion and the potential of general agreement is a thing of the past. Today, instead, “the internet and social media have become forums for noisy debate and extremist voices.” This is, “a period of profound and loud fragmentation and disagreement on many issues that do not neatly split into left and right, Leaver and Remainer, disabled and able-bodied, straight versus queer, or any other easy divisions.” Within these conditions, exacerbated recently with pandemic restrictions, a “retreat to the comforts of fandom and physical spaces is no longer untroubled” (Andrews, 2020, p. 902). Conditioned by digital dissensus, audiences exhibit greater affective polarization, “the tendency for partisans to view opposing partisans negatively and co-partisans positively” (Lee, Choi, and Ahn, 2023, p. 2), and are thus more likely to fall victim to (or to victimize others through) misinformation and/or conspiracy thinking given the greater propensity for differently situated audiences to feel as though they live “in different worlds, where different assertions are perceived as facts” (Overgaard and Collier, 2023, p. 2). Therefore, while the idea that “fandom is beautiful” could (or should) act as a buttress to the uglier, radicalized active audiences online, fandom is often ugly, partisan and polarized. Fans, especially the most avid among them, tend to be “flooded with affect” (Hills, 2015, p. 100) and driving this change:

Social media acts as an intensifier, and the fans are the people you hear most often and associate most with a cultural or political property in the digital dissensus. The most hardcore fans and anti-fans share receipts (screenshots of evidence, such as private messages or previous social media posts) in order to defend or discredit big names in their field and will cause social media “pile-ons” or even organised (via private group chats) “brigading” of individuals that are experienced as high-volume attacks. (Andrews, 2020, p. 903)

Just as the squeaky wheel tends to get the grease, the loudest and most disruptive fans tend to generate the most media attention[3] and dissensus and debate takes centre stage rather than people negotiating their disagreements through civil dialogue. But disagreements (both based on temporary issues and more fundamental ideological entrenchments) and uncivil behaviour comprise just the tip of the proverbial iceberg: Consider what de Vreese terms “the research agenda of a communication scholar: “a) Spread of mis- and disinformation; b) polarization of and by political elites, in the media, in media use; c) increasing distrust of journalism and news avoidance; and d) changing (read ‘worsening’) civil discourse, especially online” (2021, p. 215). These topics characterize some of the topographical character of our contemporary condition wherein audiences are subsumed by ‘dark participation,’ “the evil flip side of citizen engagement” (Quandt, 2018, p. 37). This concept was created as “a counter-concept to a ‘naïve,’ abundantly positive and ‘pure’ concept of user participation discussed in communication studies and journalism roughly around the turn of the millennium and the subsequent decade” (Quandt, 2021, p. 85). You might recognize this as the broad contours of what we earlier termed ‘participatory culture,’ rooted in “some enthusiastic and rather utopian ideas” (Quandt, 2018, p. 37). Not all audiences, as we’ve seen, are produsers or altruistic activists; many are motivated by self-interest and mercurial or sometimes even hateful agendas.

Dark participation “is characterized by negative, selfish or even deeply sinister contributions such as trolling … and large-scale disinformation in uncontrolled news environments” (Quandt, 2018, p. 40). Misinformation, propaganda, or any bullying or hate-based campaign organized against any person or group can be seen as dark participation.[4] Of course, there are important differences between such types of dark participation. Consider Quandt’s clarifications between trolling, cyberbullying, and cyber hate. The former are typically portrayed as:

angry, malevolent participants who project their personal issues and a general hatred for fellow human beings or ‘the system’ onto others with a grim will to stir up forum debates. Also, trolling seems to be sometimes motivated by the simple enjoyment of causing turmoil and seeing others react to aggressive or nonsensical posts. … In contrast to trolling, cyberbullying is “intended to harass an ‘inferior’ victim”; it is “an intentional and deliberate act” that happens “more than once.” … Both of these types of dark participation can be differentiated from the above mentioned strategic forms of cyber hate, which are typically … targeted at whole groups defined by criteria such as race, ethnicity, gender, religion, and so on—and (mostly) not at single victims or at singular events. (Quandt, 2018, p. 41).

There are also the forms of dark participation known as participatory propaganda (Wanless and Berk, 2019) and ‘participatory conspiracy culture.‘ The latter refers to “the everyday, mundane online debates people have about conspiracy theories” (de Wildt and Aupers, 2023, p. 2). Far from positing “a homogeneous community, or even a digital ‘echo chamber’ in which participants are socialized into shared, radical beliefs” (de Wildt and Aupers, 2023, p. 10), participatory conspiracy culture is an online space where “beliefs are not consolidated nor are believers radicalized … a community in which belief is, above all, contested rather than embraced” (de Wildt and Aupers, 2023, p. 15). Here, participatory culture refracted through a dark lens is a ludic space of engagement in which “different groups were either discrediting each other’s specific beliefs; were prioritizing doubt over belief itself; or were just out there to “have fun” with conspiracy theories as entertainment” (de Wildt and Aupers, 2023, p. 10). And within conspiracy theory communities (like QAnon), leveraged participants draw upon “the participatory affordances of the social web to collectively construct knowledge that maintains the social and political cohesion of the conspiracy across time.” Alternative facts emerge from “populist expertise, the rejection of legacy media accounts, scientific consensus, or elite knowledge in favor of a body of ‘home-grown’ forms of expertise and meaning-making generated by those who may feel disenfranchised from mainstream political participation” (Marwick and Partin, 2022, p. 3).[5]

Trolling, I think, deserves special mention.

Because of the varieties (and visibility) of dark participation, Quandt suggests differentiating between five main dimensions of the concept: “(a) wicked actors, (b) sinister motives and reasons for participation, (c) despicable objects/targets, (d) intended audience(s), and (e) nefarious processes/actions” (2018, p. 41). Individuals, groups, social movements can all be motivated to act in a wicked fashion by sinister reasons, targeting a variety of social actors in order to, in turn, affect a wider intended audience. And, of course, this can happen in unstructured and random moments or via strategic and concerted long-term campaigns. The really significant factor is how normalized this type of participation is, for unlike the utopian strain of participatory culture asking individuals to connect with others as ideal citizens, dark participation does not require people to work together towards a higher good. Rather,

[It] does not rely on an idealistic general audience as participators, but is driven by very particular, often selfish interests of specific individuals and groups. The dark participators have extreme ideas and messages, and they try to get these out into the public with missionary zeal and by any means necessary. So while the enthusiastic concept of participation expected exceptional motivation from the normal audience, dark participation merely assumes motivated exceptions from the norm. (Quandt, 2018, p. 43)

To be honest, “the dark participation concepts can leave a scholar or citizen in a depressed mood” (de Vreese, 2021, p. 215), but that is not the goal of concluding this section on this note. Instead, the goal was to present a counter-point to the evangelizing of those who would have you think that participatory culture was all about positive engagements with media and with each other. Negative or regressive engagement is also a hallmark of the most emotion-laden audience activity in the participatory era, challenging progressive hopes and dreams with open-eyed acknowledgement of “trolling, incivility, conspiracy, mis- and disinformation, automated pollution of the information environment, populism, and democratic backsliding” (de Vreese, 2021, p. 216). But still, darkness is not all-encroaching. While de Vreese asks the question, I assert that there is (and must be) “space for optimism and a positive research agenda” (2021, p. 216).[6] This need not be the false optimism of always looking on the bright side of life.

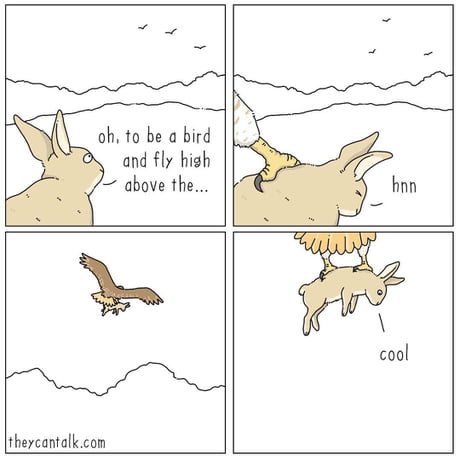

Perspective is everything! (as the following two images depict).

Perspective is everything! (as the following two images depict).

![Always look on the bright side of life [OC] | r/wholesomememes | Wholesome Memes | Know Your Meme](https://i.kym-cdn.com/photos/images/original/001/536/211/ca8.jpg)

Rather, it entails a “light after darkness” philosophy – the kind of thing Leonard Cohen sang about when he proclaimed “There’s a crack in everything, that’s how the light gets through.” This means going beyond bemoaning dark participation and digital dissensus (or even the fatalistic attitude of “if you can’t beat them, join them”) and looking for moments of (and mechanisms for) audiences contributing positively to their communities and to healthy public debate. Rather than assuming something is clearly either good or bad content, we maybe ought to look through an open lens (or at least a widened aperture) at both light and dark content, toxic and not, in order to fully explore the implications of and potential for the wide variety of participation available to audiences today. It also suggests that audiences have power beyond that of reacting to media. The concept of reactionary fandom is a good one, but I like the idea of response-able fandom too. Click on the following (non course-based, non-academic, just generally insightful albeit neoliberal-esque) link to learn more:

How we can take control of our reactions

How do we want to respond to the current circumstances? What do we want to do, how will you choose between dark and light and not get sucked into an endless miasma of grey? The prospects for us as audiences are exciting. It reminds me of the phrase, “May we live in exciting times”. This is both a blessing and a curse. And it is a great way to end, just as Quandt (2021, p. 84) began, with the famous opening paragraph from Charles Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities:

It was the best of times, it was the worst of times,

it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness,

it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity,

it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness.

References

Andrews, P. (2020). Receipts, radicalisation, reactionaries, and repentance: the digital dissensus, fandom, and the COVID-19 pandemic. Feminist Media Studies, 20(6), pp. 902–907.

de Vreese, C. (2021). Beyond the Darkness: Research on Participation in Online Media and Discourse. Media and Communication, 9(1), pp. 215-216.

de Wildt, L., & Aupers, S. (2023). Participatory conspiracy culture: Believing, doubting and playing with conspiracy theories on Reddit. Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, 0(0) 1–18

Hills, M. (2015). Doctor Who: The unfolding event: Marketing, merchandising and mediatizing a brand anniversary. London: Palgrave Pivot.

–. (2018). An extended Foreword: From fan doxa to toxic fan practices? Participations 15(1), 105-126.

Jenkins, H. (2006). Convergence Culture.Where Old and New Media Collide. New York: New York University Press.

Lee, S., Choi, J., & Ann, C. (2023). Hate prompts participation: Examining the dynamic relationship between affective polarization and political participation. new media & society, 1–19.

Marwick, A. E., and Partin, W. C. (2022). Constructing alternative facts: Populist expertise and the QAnon conspiracy. new media & society, 1–21.

Overgaard, C. S. B., & Collier, J. R. (2023). In different worlds: The contributions of polarization and platforms to partisan (mis)perceptions. new media & society, 1–19.

Proctor, W. (2017). ‘“Bitches ain’t gonna hunt no ghosts”: totemic nostalgia, toxic fandom and the Ghostbusters platonic’, Palabra Clave 20(4), 1105-1141.

Proctor, W., & Kies, B. (2018). Editors’ Introduction: On toxic fan practices and the new culture wars. Participations 15(1), 127-142.

Quandt, T. (2018). Dark Participation. Media and Communication, 6(4), pp. 36–48.

–. (2021). Can We Hide in Shadows When the Times are Dark? Media and Communication, 9(1), pp. 84–87.

Scott, S. (2018). Towards a theory of producer/fan trolling. Participations 15(1), 143-159.

— (2021). Food poisoning: The Rick and Morty Szechuan Sauce debacle and the temporalities of toxic fandom. In CarrieLynn D. Reinhard, Julia E. Largent, and Bertha Chin (Eds). Eating Fandom: Intersections Between Fans and Food Cultures (pp. 59-70). Routledge.

Wanless, A. and Berk, M. (2019). “The audience is the amplifier: Participatory propaganda.” The Sage Handbook of Propaganda. Sage: London.

Williams, R., & Bennett, L. (2022). Editorial: Fandom and Controversy. American Behavioral Scientist, 66(8), 1035–1043.

Willson Holladay, H., & Click, M. A. (2019). Hating Skyler White: Gender and Anti-Fandom in AMC’s Breaking Bad. In M.A. Click (ed.), Anti-Fandom: Dislike and hate in the digital age (pp. 147-165). New York University Press.

- For further details, see https://www.polygon.com/2017/10/9/16447460/rick-and-morty-szechuan-sauce-mcdonalds-fans-anger ↵

- see https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/tv/tv-features/justin-roiland-animation-empire-implosion-rick-and-morty-1235319366/ ↵

- see the way the media covered the great McDonalds Szechwan sauce freak-out for clear evidence of how boisterous and unruly fans tend to become the hallmark fans in the public imagination. ↵

- Interestingly, the International Association for Mass Communication Research has a special section dedicated to audiences and it identified the following theme as its first specific area of interest for those thinking of proposing a paper for their 2024 conference: "Authentic and inauthentic audiences. During the past years the media landscape has been plagued by the concept of post-truth, thus reconfiguring audiences and reception of the content and information. Audiences are reconfigured in the context of the regimes of truth, post-truth; information and mis-disinformation. These contexts include not only authentic actors but also algorithmic, bot-based behaviors" (see https://iamcr.org/christchurch2024/cfp-aud). Interesting, this aligns quite well with the announcement of 'authentic' as the Merriam-Webster 2023 word of the year, a word redolent with meaning for influencers and anyone confronting artificial intelligence, deep-fakes, etc. ↵

- All of this talk of propaganda, conspiracy theories, misinformation, disinformation, and so on leads me to make one final appeal - if you're interested in these contemporary concerns (and related concepts like manipulative strategic communication, post-truth, alternative facts, etc), don't forget that they form the basis of my Winter 2024 course COMM 3P51 (Language and Public Communication). Interestingly, I've changed the course calendar description so future versions of the course will describe it better as "Communication and Public Manipulation." Yes, the content that forms the basis of the ending of this course also serves as the foundation for my next course. Keep this stuff in mind if, in January, you're thinking 'dang, I sure would like to take another course with that Foster cat' (because that's how everyone talks these days...) ↵

- Super stealth (and self-interested) footnote here: My last addition of information that might otherwise interrupt the flow of the main text but which is interesting or contextually relevant... If you read the last footnote about how this course relates to a course I'm teaching next term, this one references a course I'm teaching next year. COMM 2Q93 "Positive Communication" will deal with exactly this question that is too often marginalized from research agendas primarily occupied with a critical perspective and aiming to tear something down. The course calendar description reads: A critical focus on how communication and media facilitate people to “feel good” and to lead a “good life.” Topics may include happiness, flow in professional pursuits, peak communication experiences, relational well-being, and positive experiences that can be obtained through the consumption of media content. It is envisioned as a course that focuses on the link between communication, happiness, health (in its broadest sense - mental, emotional, physical, spiritual), and wellness. It speaks exactly to these memes and cartoons I've included in the main text too: Positive communication is not about naively attending to only good things (i.e. being overly optimistic or avoiding a critical perspective), but about applying and studying communication that allows us to thrive and flourish. I envision this course touching upon topics that might normally fall under the rubric of interpersonal communication (optimism, hope, affection, celebratory support, excellence, forgiveness, fun, humor, interpersonal growth, interpersonal synchrony, intimacy, listening, positive conflict, social support, and virtue) but also explore these within the context of what a ‘good life’ might look like in a contemporary, mediatized society. If you've read this far, your curiousity is piqued at least. So, yeah, if you've liked the "vibe" in this course, and you're looking for an extra elective credit to pick up next year, consider COMM 2Q93. Its status as a COMM xx9x level course means it can be flexibly fit in to almost any course plan where an option (and an interest) exists. That's it! My final personal aside to you in this course. Take care! ↵