4 The Audience Commodity

So far, we have placed the focus on the activity of audiences, exploring how audiences participate in the media circuit of culture and communication. This chapter shifts the focus to highlight how media industries understand, control, and commodify audiences (especially in a participatory culture). To put it simply and to contextualize earlier material, “the more people occupy fandom as an identity, the more media industries will capitalize on turning that identity into a site of commodification.”[1] We have, to this point, emphasized the explosion of (and the implications for) opportunities for user generated content, charting the ways in which audiences have been viewed as passive receivers, and then active consumers, and finally productive users. But it is useful to also clarify that audiences are not simply players in an information society, but players in an information economy. And as much as we can celebrate the resistant practices of fandoms revelling in their exploits, we must also recognize that these same fans are being exploited by the media industries in which they operate.

For “media still depend on human participation, but now users are also supplying content. And they are doing so free of charge to media owners who profit from their labor in blogs, vlogs, social-networking sites, citizen journalism, and even advertising.”[2]

We exist in a situation where we can profit as individuals from our active engagement in participatory culture, but at the same time, others profit from our activity. Audiences don’t just consume media commodities; in the act of consumption, audiences become commodities. Before we examine how this happens with produsers, we need to widen our aperture a bit and examine how this happens with everyone. And to do so, we ought to clarify what this perspective on audiences is all about (hint: it’s about power, but it doesn’t presume that audiences have it or are simply taking it back).

The concept of the “audience commodity” comes from the Canadian Political Economist Dallas Smythe who “stressed the importance of studying media and communication in a critical and non-administrative way”[3] He argued that too much marxist critique of the media focused on their ideological manipulation of audiences. Instead of emphasizing the degree to which the media operated as part of the “superstructure” of society, influencing the way people think and shaping their consciousness, Smythe emphasized the economic base of the media, focusing on the economic functions they serve in capitalism. While media obviously still function ideologically, encouraging beliefs, attitudes and ideas, the construction of “false consciousness” wasn’t as important as its material function, both encouraging audiences to buy commodities and delivering those audiences to advertisers as commodities. Smythe “wanted to open up the debate for also giving attention to the media’s capital accumulation strategies that are coupled to its role as mind manager.”[4]

“At its core, political economy focuses broadly on social theory by connecting the systems of the economy—the organization of corporations, the structures of a marketplace, and the behavior of market players—with notions of resource availability and power.” Beyond media, it “is critical in nature, centering on problems of inequality and social justice by exploring the economic, social, and institutional forces that support the status quo.” When it comes to media, “political economic analyses place particular emphasis on the social and economic transformations that have occurred as a result of industrialization and rise of corporations within a capitalist system.” This system creates a divide between ‘spaces of production’ such as the workplace in which “workers expect to be closely monitored by their employers—and spaces of leisure—where the home and domestic sphere are separated from the public realm and individuals are granted autonomy and privacy.” And more than just producing products for people to consume in their homes (like TV series, music, podcasts, sporting events, etc.), “media corporations must find some way to break into this private realm to measure and catalog consumers’ behaviors for commercial purposes.” When it comes to audiences in particular, taking the example of a TV production, “at the same time that the television program is being “sold” to the audience, the attention of the audience is being ‘sold’ to advertisers.”[5] Smythe suggested that a lack of attention to the

issue of audience labour was the “blindspot” of communication research. So much attention being spent on media content (that we can see) and debate over representations and media effects allowed the real importance (and real danger) of media to go unnoticed. We ought to be aware, instead, of how audiences function within the economic system of capitalism, generating value for advertisers.

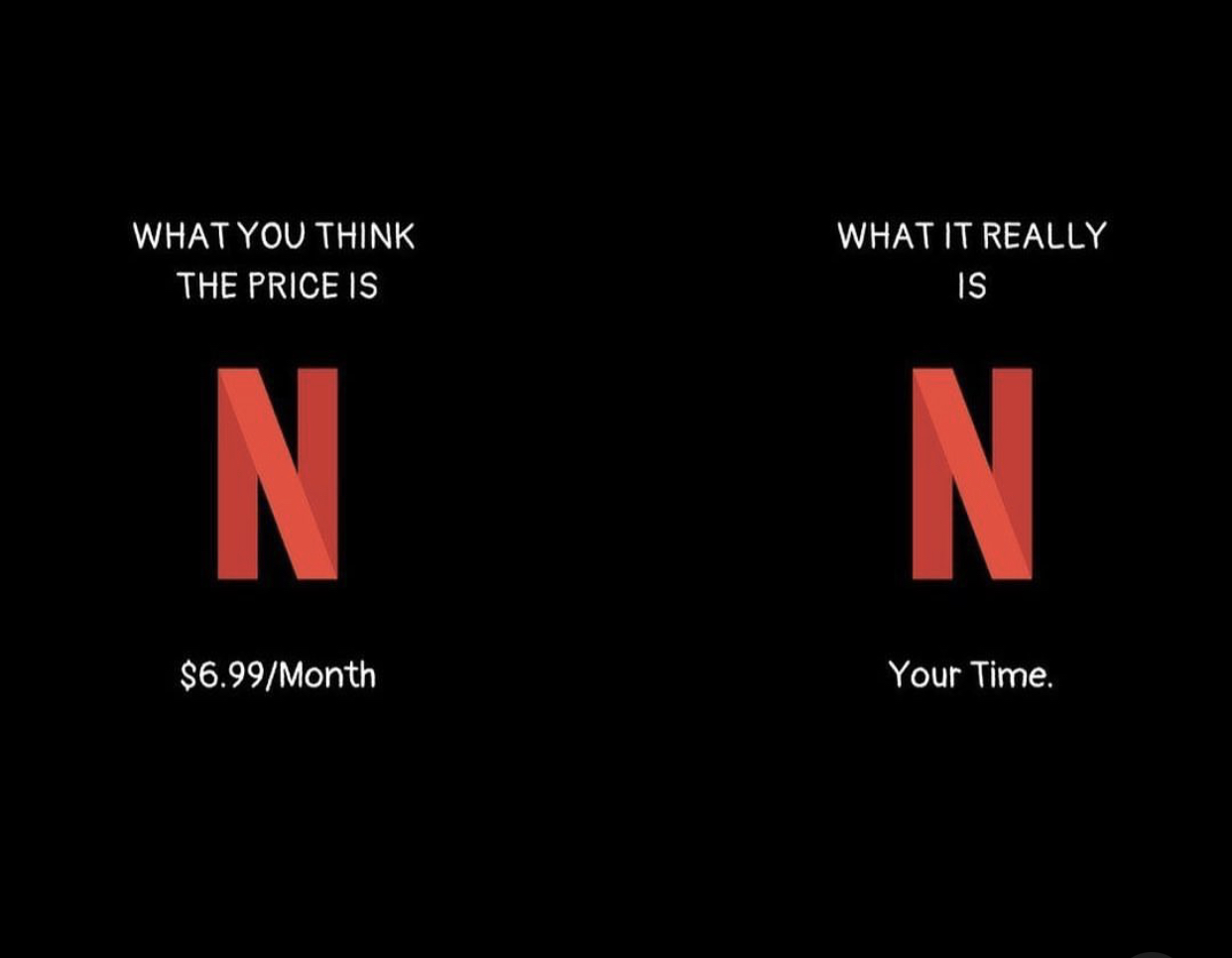

If we are to take this metaphor of the blindspot literally, we ought to ask what is being missed when we focus on audiences consuming content rather than audiences existing as content. What is the danger that lies beyond our (myopic) view? If we shift our focus, instead of producing content for audiences, we see producers in capitalist media systems producing audiences that can then be sold to advertisers (or really, exchanged for advertiser dollars). Media industries are akin to a “cat burglar” distracting a guard dog with a juicy steak. The content is the steak.[6] Distracted by the “juicy piece of meat” (and often engorged on it), we lose sight of what’s really happening, too happy with what we’ve already received. But what’s really happening is something of value is being taken from you, not given to you. Your time is valuable. But we so often give it away for free (as the following image depicts):

In capitalism, making meanings is secondary to making products (because we make profit off of products, not meanings). Most of us aren’t used to thinking about all of our time being profitable, much less valuable, but some, like lawyers, are. Their value, to the law firm, is in the billable hours they can bring in. All time spent on an account is billable.

As Smythe argued, under capitalism, when you’re not sleeping, you’re working.[7] All time in capitalism = worktime (not just when you’re working). We are labouring all the time, except most of the time, we aren’t paid for our labour. And since when we’re working at our jobs, we get paid for our labour, we tend to devalue all the labour we put into our other activities. Hence, even though we spend an awful lot of time with our media, we think of it as a leisure activity rather than a productive one. Yet when we are consuming, media platforms extract value from us and our attention (really the time we spend on their platforms) in the form of user data that is then sold to advertisers who, knowing more about us, can better target us and our wallet knowing about our demographics, habits and propensities. What the audience does or what it thinks is secondary to the media business that is the production and sale of the commodity audience. Here, all content of commercial media, in essence, is offered as a “free lunch” to get you – the audience to come and pay attention. Then, the audience can be measured and categorized and you as an audience member can be then offered for sale to advertisers.

Far from a cultural studies view of audiences that located their productivity in the meanings they generate from media texts, a critical political economy view sees audiences’ productivity in terms of their economic activity. While both cultural studies and political economic studies of audiences rejected earlier traditions of viewing the audience in technical, administrative terms, they tend to approach the need for research into public interests, communication rights, and consumption practices in different ways. “Cultural studies scholars challenge the presumption that audiences are easily manipulated by mass media”[8] while a political economic view tends to take a more critical and industrial view of cultural participation, public engagement, and the dispersal of power. Whereas a cultural studies point of view tends to discuss audiences as citizens, fans, and players, a political economic point of view tends to debate audiences’ role as victims, consumers, and commodities.

Of course, “claims about ‘the audience’ shift as political economy and cultural climates shift, enabling different constituencies to argue their case and so advance their interests.”[9] Produsers are clearly a different kind of commodity audience than the person sitting at home merely enjoying the content of mass media as a viewer-bystander. Smythe’s writing related to a pre-internet era. It was arguably a more radical idea, then, to consider the act of watching TV (and therefore the consumption of commercials) as a “form of productive labor that generates economic value (and surplus value) for broadcasters, for which the audience receives “payment” in the form of the programming itself.” Today, with the platforms that people depend upon for their daily lives (much less entertainment) themselves depending on advertising[10], we can almost take for granted that, as audiences, we are being bought and sold as commodities. The more productive we are as consumers and users of online content, the more valuable our data is to someone else. We are our eyeballs. Commercial media, whether it be traditional mass broadcasting or niche streaming of digital content, depends upon the sale of audiences’ attention to advertisers.[11]

Participatory culture, in fact, while it has a long history of seeming laudatory when it comes to audience practices, has always had a connection to economics with Jenkins’ early conceptualization of affective economics: “According to the logic of affective economics, the ideal consumer is active, emotionally engaged, and socially networked.”[12] For instance, it has been argued that YouTube operates within an “affective economy” in which success is determined by participation, interaction, and the sharing of seemingly ‘authentic’ emotion.[13] When he first used the term, Jenkins classified affective economics as “a new discourse in marketing and brand research that emphasizes the emotional commitments consumers make in brands as a central motivation for their purchasing decisions.”[14] This leveraged the blending of producer and consumer power via interactive media, “allowing advertisers to tap the power of collective intelligence [of consumers and] … allowing consumers to form their own kind of collective bargaining structure that they can use to challenge corporate decisions.”[15]. Clearly, this concept invokes producers with the power to exploit audiences’ emotional connections with their products, even as it suggests that audiences’ have the relative power to either bestow or withdraw their emotional capital in the media marketplace. Fans who bestow their capital (both emotional and monetary) “feel the love,” and the most participatory of fans engage in “labours of love” for their fellow fans, creating new texts and new meanings within their communities.

This discussion of love, either to be manipulated by corporations’ gain or operationalized for consumers’ benefit, reminds me of the idea of a ‘lovemark,’ used “to illustrate how brands often try to make their consumers fall in love with them.”[16] Lovemarks are seen quite often in “brandom,”[17] a term used to describe controlled and uber-commodified brand-focused fandom, “the pseudo-fan culture engineered by brand managers eager to cultivate consumer labour and loyalty while preempting the possibility of resistance that participatory fan culture promises.”[18] Lovemarks, or positive affective impressions left upon the consumer, transcend mere products or brands. Products are base commodities, purchased out of necessity or habit, but with a low investment of love and respect. Brands tend to be respected more (i.e., a trusted brand), but still not loved by consumers whereas the lovemark is the brand with which one has a high emotional connection. “In short, affective economics mobilises a concept of emotional engagement between consumers and branded goods in order to position itself as beyond mere ‘commodification.’”[19] The “lovemark” is like a trademark, but suffused with affective intensity and, thus, it is no longer the exclusive purview of owner-producers. Instead, “lovemarks are not owned by the manufacturers, the producers, the businesses. They are owned by the people who love them.”[20] In participatory culture, affective economics is more than just a marketing strategy designed to cultivate and embrace fans; more than just ‘exploiting’ fan engagement, it acknowledges the (market) power of audiences’ emotional involvement with the stuff that they love. The lovemark is not possible without the affective labour of audiences:

Consumer activities ranging from purchase and use to displaying and advocating for the brand in social networks, responding to invitations from the brand to participate in events and online communities, and generally embedding the brand in their everyday lives, can be understood as necessary affective labor without which the brand has no sustainable value.[21]

Just as the commodification of the audience was a blindspot of communication research, but no longer operates in the background of more manifest concerns about the media, a focus on affect suggests that “the function of media as a socialising/ideological mechanism has become secondary to its continuous modulation, variation and intensification of affective response in real time.”[22] It is important to note that, just like fandom is never individual, “affect is not the property or creation of the labourer, but is found in the capacity of the labourer to channel and modulate social connections, ideas and feelings.”[23] Fans are the most organic of affective labourers, producing affects “such as feelings of ease, well-being, satisfaction, excitement, or passion”[24] within themselves and within fan communities (even as marketing professionals seek to exploit those feelings also). Affective labor, then, can be considered as “any commodified activity that is not, in a conventional sense, considered ‘work.’”[25] In participatory culture, all produsers (fans or otherwise) are labouring.

It would be erroneous, however, not to acknowledge that even with participatory audiences expressing more power, “a shifting logic of media engagement is accompanied by revamped strategies for managing and manipulating audiences.”[26] Clearly, not all media engagement is of a utopian nature. To address this, one way of speaking critically of participatory culture is by invoking the concept of communicative capitalism. This is “the common-place idea that the market, today, is the site of democratic aspirations.”[27] Far from seeing twenty-first-century media prosumers expressing their agency and deploying convergence culture to participate in ‘knowledge communities’, communicative capitalism “tricks citizens into believing that the volume of information surfacing in new communication venues generates real institutional transformation, political resistance, and democratic outcomes.”[28] Digital interconnection does not mean digital empowerment. According to this view, “the trumpeting of convergence culture … underestimates the political-economic vulnerability of the populace. They can use digital networks to amplify their voices, but they are rarely heard by political or corporate elites who still dictate the distribution of societal resources, including capital and the information and communications technology (ICT) infrastructure.”[29]

“Under communicative capitalism … everyone not only has a right to express an opinion, but each is positively enjoined to—vote, text, comment, share, blog. Constant communication is an obligation” (p. 92) and all the communication is tracked, quantified, and ultimately sold as “big data.” Our contemporary communication takes place not only via affective networks, but capitalistic ones. And while the fun and the promise of participatory culture motivates audiences to participate more, we can also understand this as a disciplinary practice:

Pervasive communication can be a regime of control in which the people willingly and happily report on their views and activities and stalk their friends. We don’t need spectacles staged by politicians and the mass media. We can make and be our own spectacles—and this is much more entertaining. There is always something new to be found on the internet. Corporate and state power need not go to the expense and trouble of keeping people entertained, passive, and diverted. We prefer to do that ourselves.[30]

Indeed, communicative platforms feed on the affective behaviour of audiences, both positive (liking and sharing posts) and negative affect such as, “flame wars, spam, and strategic friending (friending not as a sign of affiliation but in order to track one’s enemy)”[31] The link between a critical political economic view of media audiences and the circulation of affect (goading those same audiences to immerse themselves ever more with participatory culture) is real:

Communicative capitalism relies on networks that generate and amplify enjoyment. People enjoy the circulation of affect that presents itself as contemporary communication. The system is intense; it draws us in. Even when we think we aren’t enjoying, we enjoy (all this email, I am so busy, so important; my time is too precious to waste on another Facebook game … but my score is going up; it’s such a burden having so many, many friends—oh, and I should tweet it so they know how busy I am).[32]

The appeal of communicative capitalism seems relatively obvious. In addition to an inherent democratizing aura, “capital not only “extracts” affect, but magnifies its impacts and unleashes its productive capacities through processes of circulation.”[33] So even though many feel a sense of community in participatory culture, we must recognize that “both community interaction and affect exist on a continuum (changing between different people and even within a person over time).”[34] And within capitalism, one has to wonder how legitimate the feelings of community are in a scene that so often privileges neoliberal tactics of self-improvement and market-based empowerment with the goal of the monetization of everything. One could go so far as to suggest that rather than producing community, “affective networks produce feelings of community, or what we might call ‘community without community.'”[35] Perhaps even community is branded in the era of the commodity audience, a promise (much like a free lunch) that keeps people coming back for more.

The casual use of the term “audience commodity” tends to ask us to focus our attention on audiences who are labouring (often becoming unwitting media commodities). Certainly fan labour is “closely linked to ‘immaterial labour’ and ‘affective labour,’ as for a ‘brand advocate’ the real reward is to help others and to spread the word about the fantastic brand they are supporting — to convert people into customers who will consume the brand, product or service.”[36] Fan-trepreneurs are an especially interesting case of this, selling their fan-made merchandise to others. But insofar as participatory culture muddies easy distinctions between producers and consumer-users, we must also remember that producers actively labour to produce media commodities to attract audiences too. This has been termed “relational labor”[37] and is especially true of influencers working to maintain their cultural capital and audience appeal. This has also been discussed relative to the K-pop industry (producing “idols” who sacrifice their privacy, education, family life, friendships and romances to maintain a loyal fan base: “They are not simply musicians but also affective labourers who perform ‘fan service’ – that is, verbal, physical, physical, textual, and/or musical performances that offer pleasure – and work ceaselessly to maintain a close relationship with their fans”[38]

This example reinforces how media texts are not simply either bearers of meanings and ideology or agents of commodification and profit making. They are, instead, always both. We need to develop a picture of audiences that are active between the twin poles of media and consumer power. It is not simply about who has the power – this debate is artificial and can never be won. Rather, an intelligent (or at least finessed) study of audiences will recognize that audiences negotiate media content delivered to them by producers. And sometimes audiences can be producers. Always, however, the encoder and decoder are in a position of asymmetry. It isn’t about saying “oh, look at the poor victimized audiences subject to exploitation by bad corporations” or “look at that, audiences now have the power!” – it’s about realizing how communication needs both, and the conditions wherein producers and audiences are situated are always shifting. Of course meaning construction (and textual construction) on the part of audiences occurs! But this doesn’t mean producer power over audiences disappears! Everyone in participatory culture is exercising their relative power and is thus an affective labourer. In the end, any level-headed study of audiences has to take into account that “the ‘cultural circuit’ linking processes of the production and consumption of mediated meanings demands a multidimensional and multilevel analysis that respects people’s agency while recognizing the significant degree to which institutions, culture, and political economy shape the contexts within which people … act.”[39]

This chapter spent some time discussing affective economics and affective labour, but still maintained an emphasis upon positive affect, only hinting at the power of negative responses. Critique focused upon corporate exploitation of affect and the capitalistic framing of participatory culture, rather than nature of the appeals and the invective that comprises that culture. The next chapter explodes the idea of negative affect. We take seriously the idea that not all participatory culture is positive and a lot of audience responses that may appear to be “fannish” in intensity are negative in content.

- Booth, Paul (2015) Playing Fans: Negotiating Fandom and Media in the Digital Age. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, p.1 ↵

- Gibbs, Anna (2011) “Affect Theory and Audience.” In The Handbook of Media Audiences (Virginia Nightingale, ed.). Malden, MA: Blackwell, p. 261 ↵

- Fuchs, Christian (2012) "Dallas Smythe Today - The Audience Commodity, the Digital Labour Debate, Marxist Political Economy and Critical Theory. Prolegomena to a Digital Labour Theory of Value." tripleC: Communication, Capitalism, and Critique, 10(2) , p. 692. ↵

- Fuchs, Christian (2012) "Dallas Smythe Today", p. 694 ↵

- Sullivan, John L. (2020) Media Audiences: Effects, Users, Institutions, and Power. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. ↵

- While maybe awkward, I really like this extra metaphor - used by Marshall McLuahan in "Understanding Media" when he suggested that "Our conventional response to all media, namely that it is how they are used that counts, is the numb stance of the technological idiot." ↵

- Smythe, Dallas. (1977) "Communications: Blindspot of Western Marxism." Canadian Journal of Political and Social Theory 1(3): p. 1. ↵

- Butsch, Richard (2011) “Audiences and Publics, Media and Public Spheres.” In The Handbook of Media Audiences (Virginia Nightingale, ed.). Malden, MA: Blackwell, p. 153 ↵

- Livingstone, Sonia, and Peter Lunt (2011) "The Implied Audience of Communications Policy Making Regulating Media in the Interests of Citizens and Consumers." In The Handbook of Media Audiences (Virginia Nightingale, ed.). Malden, MA: Blackwell, p. 185 ↵

- According to James Ball's article, "Online Ads Are About to Get Even Worse" in The Atlantic (June 1, 2023), about 80% of Google’s revenue comes from ads, while Meta makes more than 90% of its revenue from advertising. "All told, outside of China, the online-ad industry was worth about $500 billion [in 2022] ... and Google, Meta, Amazon, and Apple are believed to have taken some $340 billion of that. Companies that traditionally opposed advertising are looking for their way in too: After resisting ads since its inception, Netflix introduced an ad-supported version of its streaming service last year, as did Disney+." ↵

- Sullivan, John L. (2020) Media Audiences: Effects, Users, Institutions, and Power. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. ↵

- Jenkins, Henry (2006) Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide. New York: New York University Press, p. 20. ↵

- Burgess, Jean, and Joshua Green (2009) "The Entrepreneurial Vlogger: Participatory Culture beyond the Professional-Amateur Divide" in The YouTube Reader (Pelle Snickars and Patrick Vonderau, eds.), Stockholm: National Library of Sweden, p. 95. ↵

- Jenkins, Henry (2006) Convergence Culture, p. 319 ↵

- Jenkins, 2006, [. 63 ↵

- Linden, Henrik, and Sara Linden (2017) Fans and Fan Cultures: Tourism, Consumerism and Social Media. London: Palgrave Macmillan, p. 15. ↵

- We will address this concept in greater detail in the unit on "sport(s) fandom" ↵

- Guschwan, Matthew (2012) "Fandom, Brandom and the limits of participatory culture." Journal of Consumer Culture 12(1), p. 26 ↵

- Hills, Matt (2015) "Veronica Mars, fandom, and the ‘Affective Economics’ of crowdfunding poachers." new media & society, Vol. 17(2), p. 185. ↵

- Roberts, Kevin (2005) Lovemarks: The Future beyond Brands. New York: powerHouse Books, p. 74. ↵

- West, Emily (2017) "Affect Theory and Advertising: A New Look at IMC, Spreadability, and Engagement." in Explorations in Critical Studies of Advertising (James F. Hamilton et al., eds.) New York, NY: Routledge, p. 250. ↵

- Clough, Patricia (2008) “The Affective Turn: Political Economy, Biomedia and Bodies.” Theory, Culture & Society 25 (1), p. 16. ↵

- Carah, Nicholas (2014) "Brand value: how affective labour helps create brands," Consumption Markets & Culture, 17:4, p. 348. ↵

- Hardt M and Negri A (2004) Multitude: War and Democracy in the Age of Empire. New York: Penguin Press, p. 108. ↵

- Psarras, Evie (2022) "'It’s a mix of authenticity and complete fabrication' Emotional camping: The cross-platform labor of the Real Housewives." new media & society, Vol. 24(6), p. 1384. ↵

- Andrejevic, Mark (2011) "The work that affective economics does." Cultural Studies Vol. 25(4-5), p. 606. ↵

- Dean, Jodi. 2005. “Communicative Capitalism and the Foreclosure of Politics.” Cultural Politics 1 (1), p. 54 ↵

- Yoshinaga, Ida (2018) "Convergence Culture: Media Convergence, Convergence Culture, and Communicative Capitalism." In The Routledge Companion to Media and Fairy-Tale Cultures (Pauline Greenhill et al., eds.) New York, NY: Routledge, p. 162. ↵

- Yoshinaga, Ida (2018), p. 162. ↵

- Dean, Jodi (2015) "Affect and Drive", p. 93 ↵

- Dean, Jodi (2015) "Affect and Drive" in Networked Affect (Ken Hillis, Susanna Paasonen, Michael Petit, eds.). Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, p. 91 ↵

- Dean, Jodi (2015) "Affect and Drive" in Networked Affect (Ken Hillis, Susanna Paasonen, Michael Petit, eds.). Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, p. 90 ↵

- Emily West, "Affect Theory and Advertising," p. 251. ↵

- Busse, Kristina, and Jonathan Gray (2011) "Fan Cultures and Fan Communities." In The Handbook of Media Audiences (Virginia Nightingale, ed.). Malden, MA: Blackwell, p 434. ↵

- Dean, Jodi (2015) "Affect and Drive", p. 91. ↵

- Linden and Linden, (2017) Fans And Fan Cultures, p. 71. ↵

- Duffy, B. E. (2017). (Not) getting paid to do what you love. Yale University Press. ↵

- Choi, Stephanie (2023) "K-Pop Idols: Media Commodities, Affective Laborers, and Cultural Capitalists" in Suk-Young Kim (ed.) The Cambridge Companion to K-Pop. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, pp. 139, 141. ↵

- Livingstone, Sonia and Kirsten Drotner (2011) "Children’s Media Cultures in Comparative Perspective." In The Handbook of Media Audiences (Virginia Nightingale, ed.). Malden, MA: Blackwell, p. 410. ↵