6 Political Fandom

This chapter is termed “political fandom” – a concept in circulation to mean “’the regular, emotionally involved consumption of a given popular narrative or text’ in a political context” (Sandvoss, cited by Rodriguez and Goretti, 2022, p. 66). The ‘text’ to which people cultivate an affective attachment can be wide-ranging, given that “political fandom can be defined as the emotional investment in and active support for political figures, parties, or ideologies” (le Clue, 2023, p. 3). But this chapter should perhaps be more accurately called “Fandom is political” rather than “political fandom” because while sometimes political fandom can mean a focus on fans of politics or politicians, this is not the end of the story. It is, however, a good beginning of the story, since so much of this affect-fuelled audience activity focuses on specific politicians. So, let us start by considering the example of Donald Trump. Not a traditional politician, he was a celebrity who, upon deciding to run for office, automatically became a celebrity politician. He had pre-existing fans when he hosted The Apprentice who helped bolster his cult of personality on reality TV.

But when Trump ran for President of the United States he certainly generated a lot more ‘fan’ activity.

Trump was a celebrity brand who became a celebrity politician. Similarly, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez turned her social media savviness and outsider moxy into a political brand, leveraging fans’ user generated content and spreadable media to great effect in a Web 2.0 environment. This makes sense considering that “the fan object, in political fandom … resembles the vague textual formation we also describe as ‘brand’” (Sandvoss, 2013, p. 278), and “media fragmentation also authorizes brand membership as a form of civic participation” (Ouellette, 2012, p. 188). Thus, following and engaging with Trump or AOC on platforms like Twitter counts as an act of citizenship, a form of political fandom. With the right fans prepared to show their support and share their love, political branding burnished by participatory culture can be more valuable than public service (Ouellette, 2012, p. 191). And even though Dean goes so far as to declare the equation of politicised fandom with ‘fans of (specific) politicians’ as ” rather banal” (2017, p. 411), the more generic suggestion that, “political participation can be seen as a form of (political) fandom” (Sandvoss, 2019, p. 125) can be equally frustrating. After all, is all political participation fan-like?

Certainly, if the extent of one’s participation in politics is voting once every four years (or even occasionally discussing political events or figures), I’d wager the answer is no. This level of commitment and engagement is so insignificant that it does not rise to the level of participatory culture. But if one’s engagement with the world of politics demonstrates “political enthusiasm,” then one’s passion for politics (and political debate, not just delivered to you but constituted by your own participation in it) mirrors that of fans of other phenomena. Sandvoss articulates the parallels between political enthusiasts and sports fans: “Both articulate and perform a strong association with the fan object built upon a partisan identification that in turn is reflected in the presence of a strong competition narrative in fans’ discourses.” Both celebrate among remarkably similar lines, revealing “the deep emotional significance and the depth of affective investments in given causes.” Thus, “this bond – whether in political enthusiasm or other forms of fandom – reflects central aspects of the fan’s identity and her values and is therefore both political and personal. Political fandom thus articulates both ideology and identity” (2013, p. 266). If one’s relationship with politics prompts one to chart “paths through the wilderness of facts, policies, movements, issues and spin,” then fandom offers us an instructive lens for this kind of active audience behaviour (Sandvoss, 2013, 254). We can go even further. Should one “engage in commenting, relaying and ‘remixing’ mainstream media sources as part of a wider activist agenda which includes portraying one’s own point of view, fostering critical debate and broadening support for chosen causes” (Sandvoss, 2013, p. 262), that is clear evidence of fannish devotion (not just to one’s object of affection but also one’s own active role in participatory culture).

Of course, we know that not all fans are “participatory fans,” thus not all political fans are so active. But especially for those who are intensely politically involved, “participants in politics fandom … treat politics as akin to a sport, game or form of entertainment, with commentary offered on political events in much the same way that one would expect on a football match or television series” (Allen and Moon, 2023, p. 6). At the end of the day, political fandom includes both ‘fans of politics’ and ‘political fans’ as long as we can see what they care about through their practices and affective engagements in the political realm.[1] People participating in politics (from commenting online about policies or politicians, to creating content for campaigns, volunteering or protesting) are certainly political fans, but insofar as they are fans of ‘the political’ they are distinct from fans (of popular culture texts) who are political. This chapter focuses on fans of politics, a particular subsection of political fandom.

As Sandvoss argued, labels such as ‘blogger,’ ‘citizen journalist,’ or ‘activist’ are insufficient descriptors for those who are passionate about politics and for whom participation in online forums discussing and debating politics is an important part of their identity; we ought to conceptualize them as fans:

If fandom is the most personal, most dedicated form of media consumption and production – articulating a sense of who we are and strive to be through our fan engagement with the object of fandom from television shows and musicians to sports teams … then political discourses, causes and politicians appear to offer equally meaningful textual spaces for being a fan. (Sandvoss, 2013, p. 260)

Of course, even though ‘we have entered a historical moment in which political communication is filled with fandom’ (Hinck and Davisson, 2020), it behooves us to remember that “no fandom is necessarily or intrinsically political. The task at hand, then, is to theorise the conditions under which fan communities become political” (Dean, 2017, p. 411). Take, for instance, fans of “the Rock” — those who celebrate his success as a wrestling and movie icon do not necessarily dip their toes in political waters, but those who question his depictions of masculinity or ethnicity clearly get political.[2] Those fans whose media activism critiques the Rock’s own efforts at activism demonstrate how “fandom becomes politicised and takes on political significance under particular circumstances” (Dean, 2017, p. 411).[3] Dean highlights four key features of fandom and emphasizes that, “while all these features are present, to some degree, in all forms of fandom, they assume particular characteristics as fandoms become more politically charged.” These factors are (1) productivity and consumption (because audiences today are both actively producing and consuming information), (2) affect (because politics depends upon strong embodied and emotional attachments to a particular political ideal or (more usually) individuals in politics), (3) community (because to be a part of a fandom is to imagine one is part of something larger than oneself, connected to others with shared interests and concerns), and (4) contestation (because fandoms stand for something, and thus also stand against something else). “Fan communities become politicized when they speak up for and act out on behalf of particular constituencies” (2017, pp. 411-415).

A few quick emphases are in order, specifically regarding affect: We already know that the more one feels affective attachment to something, the more they will likely participate as an actively engaged audience with it. Interestingly, politics is often understood as a rational game where participation is based on intellect compared to the irrational effervescence of popular culture fandom wherein participation is often fuelled by emotion. But affect (and especially political affect) transcends ‘mere’ emotion. As Dean clarifies, beyond being ‘affected’ by an encounter, affect “references the felt change in the power of the body, the increase or decrease in perfection, felt as sadness or joy, that is, something akin to what we might ordinarily call emotion but that is not reducible to it” (2017, p. 413).

When it comes to politics, the importance of this affective response does not lie in the content of the communication that one is affected by, but rather the direction of the affective flow: “Within ordinary fandoms, the affective ‘charge’ runs primarily between fan, fan object and fellow fans. As fandoms become politicised, however, fans’ affective investments become more ‘outwardly’ oriented in the sense of being constituted by a desire to change wider society” (Dean, 2017, p. 413). As one finds others who share their affective investment in an object of affection, they also find the possibility of a community. But just as not all fans operate in fandoms, not all fandoms are equally communal. Indeed, political fandom might exhibit a certain degree of “affective shrinkage,” not in terms of intensity but in terms of scope. Just as most fans are not “participatory fans,” most engage in more of an “interpretative fair” than an “interpretative community”:

[People seek] narratives… that correspond with their expectations and that support their affective reading of the fan object. It is in this process of seeking to maintain the horizon of expectation through textual selection that underpins the affective bond of fans’ investment in a given fan object, that, I think, the real impact of fandom on the political process can be found. (Sandvoss, 2013, p. 278)

Put simply, not all (political) fandoms look outward; many end up reflecting their own distorted views back to their members, naturalizing them, almost in a carnival-like, fun-house of mirrors style, or what Sandvoss terms “communicative silos” (2013, p. 279). Communities vary in the level of intensity and commitment with which fandom is felt and enacted, and communities also vary in terms of power dynamics and their sense of inclusion. “While this may mean that all fandoms are political in the broad sense constituted by diverse modes of power, inclusion and exclusion, it is still … fruitful to identify fandoms which are more overtly politicised than others” (Dean, 2017, p. 414). And this is where we see fandom as a series of affect-fuelled contests.

While less politicized fandoms may still contest certain readings of texts, resisting apolitical or mainstream interpretations, “more politicised fandoms … are sustained by the intentional collective pursuit of a particular vision of socio-political change, in opposition to, rather than to merely distinct from, some aspect of wider society as it is presently constituted” (Dean, 2017, p. 415). A fandom becomes politicized when its political enthusiasms get focused outward, rather than inward, and when its affective intensities are directed toward challenging aspects of politics and society. Rather than just standing for something or railing against some external object, politicized fandoms “are proleptic; that is, oriented towards impacting upon future society” (Dean, 2017, p. 415).

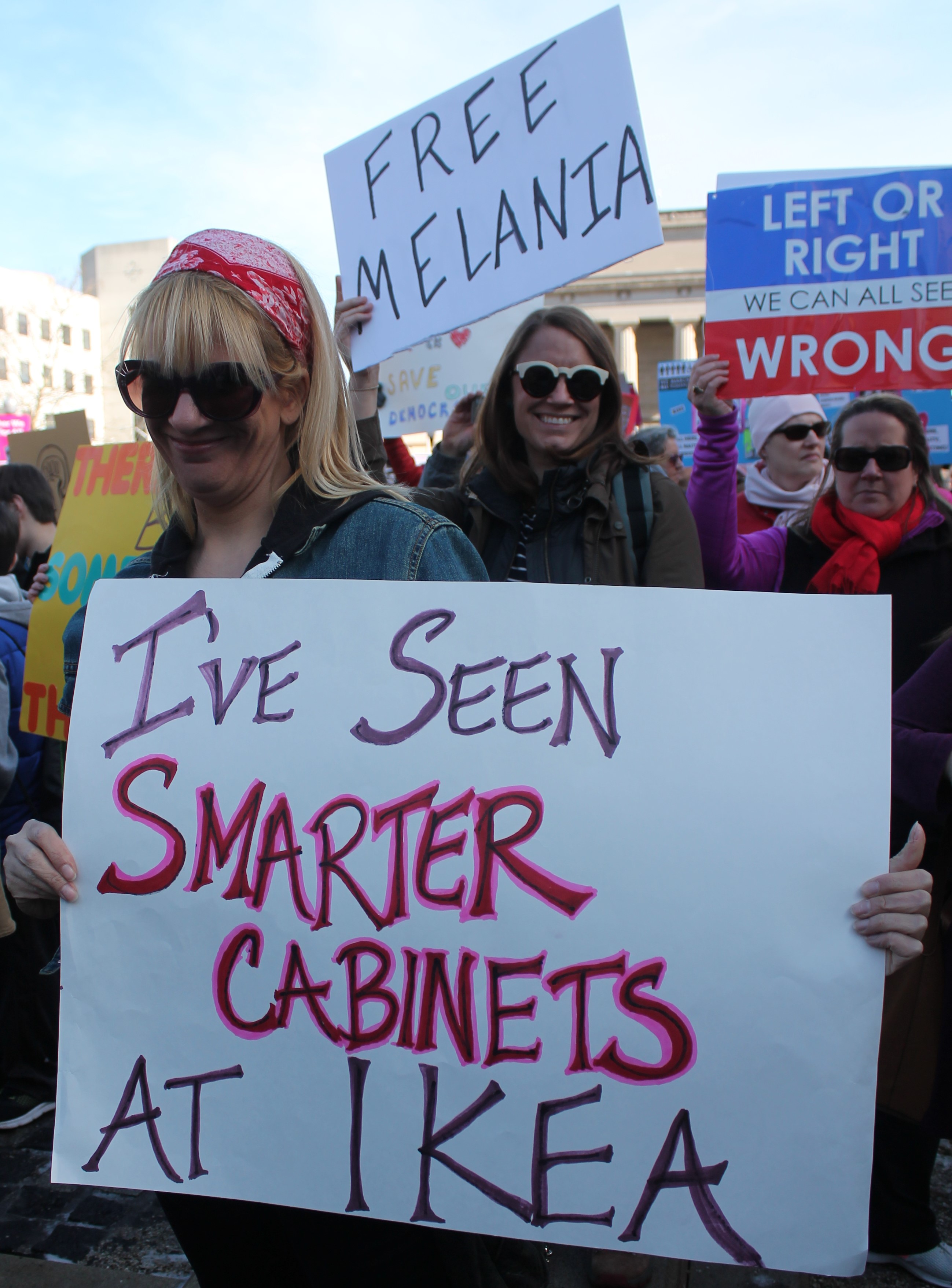

Inspired by their fandom, and motivated to transform current political parties and policies that they reject, fandoms contest the injustices that typify the present. Thus, politicized fandom is always constituted by anti-fans. “As in other fan cultures, the textual field of mediated politics thus serves as a cultural language in which meaning is signified through its antonyms as much as through its positive affirmations” (Sandvoss, 2013, p. 266). Obviously, some political ‘fans’ are fans of the political in general, but more accurately ‘anti-fans’ of certain political figures:

These examples highlight the highly polarized nature of the hyper-partisan contemporary political scene. The roots of this contemporary division can be found in the modern fragmentation of the media communication environment. Whereas once upon a (recent) time, people received their news and information through broadcasting, with choices limited to a few broadcasters all sharing relatively the same content and producing ‘aggregate audiences for national culture’, today the splintering of that audience with specialized cable channels and individualized programming via various digital platforms and the World Wide Web manifests as narrowcasting. This is predicated upon audiences who

are deeply divided by lifestyle and taste; nationalist popular culture manifests ‘more as another niche market (those people who hang flags on their cars) than as a unifying cultural dominant.’ … Something similar has happened with political culture, when differences steeped in class, region, race, gender, and generation, as well as party membership, are amped onto taste cultures and consumer markets. (Ouellette, 2012, p. 188)

Clearly, just like Trump acts as a lightning rod for people’s political opinions, anti-vaccine and anti-Trudeau ‘fans’ (flying flags and banners from their cars) similarly demonstrate how fannish behaviour translates to the political realm. “Fan identity provides a useful vocabulary for understanding politics in a time of increasing antagonism”[4]. The previous chapter ended by emphasizing how certain topics, like politics for instance, are ripe with antifandom. In fact, “although relatively uncommon in entertainment fandom, anti-fandom is particularly prevalent in the more tribal and antagonistic terrains of sport and politics” (Dean and Andrews, 2021, p. 325). In fact, Gray’s (2019) typology of anti-fans can be explicitly tied to the political realm: Competitive anti-fandom can be seen when someone in the United States who is a Republican is expected to hate the Democrats or, by extension, Liberal voters (or N.D.P. or even Green Party supporters in Canada) are pitted against Conservative voters. In contrast, bad objects anti-fandom can be seen in the anti-vaccine, anti-lockdown movement, which was arguably driven by a collective dislike of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau rather than a unified vision behind the 2020 Freedom convoy and trucker protest that shut down Parliament and turned downtown Ottawa into a spectacle of hostility cum community. Anti-fans antifandom can be seen in those who direct their anti-fandom against fans of a political party or particular politician simply because something is important or popular with them, i.e. bemoaning the stupidity of those who follow Trudeau’s “radical woke agenda.” Disappointed anti-fandom can be seen in the textual productivity of those rejecting contemporary policies of a political party that they traditionally supported, or those critical of current leadership while expressing nostalgia for the leaders and the ideological positioning of the party in the past. Monitorial hatewatching is evidenced in those who consume but also deride political coverage, often to ensure that they are up to date for their casting-of-shade. This can overlap with cynical hatewatching (those whose political consumption (and production) are typified by a lament for politics in general) or visceral hatewatching (those who tune into political news that they hate simply to feel annoyed or anger because it is better to feel something than nothing at all). This kind of zeal, while maybe not typically seen as political fandom, will never be mistaken as political apathy. We can see deep anti-fandom in someone who may identify as liberal and therefore refuse to engage with any ideas put forth by a conservative. Finally, fleeting anti-fandom can be seen in temporary aggregations of dislike, dislike, or disgust, typically focused on some momentary “Other” in order to rally disparate groups to a political cause. “NIMBY” (or “not in my backyard”) issues such as debates over safe-injection sites in neighbourhoods are a clear example of this.[5]

In order to go into greater detail about how fandom and participatory culture intersect with the world of politics, we should clarify the concept of a “politics of against,” the generative force behind a lot of anti-fandom in general and political anti-fandom, in particular. Sandvoss examined a case of political activism that was derived less from an initial positive identification with a given fan object, and more from a politics driven by acts of dislike, rejection and anti-fandom. He termed this a “politics of against” or, “the essence of a political movement primarily formulated against a symbolic Other, devoid of any material objectives” (2019, p. 131). This politics is defined by fan-like activism motivated by the rejection of “an anti-fan object – a text or textual field (such as a politician, political party, or political cause) with which users regularly and emotively engage, yet through strongly negative emotions” (p. 131-2). It acknowledges that even as much as politics is about forming connections with others (and forming communities of interest with them), “politics is about who we are – often in contradiction to ‘them,’ to the types of people that are not fully part of our imagined community” (p. 132). This politics is driven by dislike, fear, hatred, disillusionment, and finds an easy association with fandom which “effectively operates through a matrix of binary distinctions,” (p. 134) often organizing itself against the mainstream (first wave), against other fandoms (second wave), and against perceived but associated injustices in the world (third wave). Key to this idea is a sense of “othering” that is necessary to form the collective, where we see how “hatred or dislike is the rallying point for activism and enthusiasm rather than being ‘for’ a particular cause” (Barnes and Middlemost, 2022, 1126). We can see this foregrounded in QAnon’s radicalization of “normies” against mainstream politics and in the background of fans’ identification with Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, motivated by a resistance to and disidentification with President Trump.[6]

While there are, naturally, differences in textual and enunciative productivity in communities that coalesce around popular entertainment versus political information, a point acknowledged by Sandvoss (2019, 129), engagement with politics can also be entertaining too.[7] And Web 2.0 makes such engagement easier than ever before to both see and share such productivity. Beyond the spreading of political viewpoints online and the greater access to others who share similar political affiliations, we can also see how textual poaching can be recast as “political poaching” or the idea that participatory culture forces a re-evaluation of “the relationship between citizen and political campaigns” (Booth et al., 2019, p. 2). Through interventions such as the playful deployment of memes and the use and coopting of hashtags, we can see how the empowerment of “everyday non-institutional individuals to manipulate existing public discourse in new ways’ (Booth et al., 2019, p. 4).

To wit, Dean and Andrews note the fanification of political culture with citizens’ “fan-like attachments to politicians, whereby selfies with politicians, or the sharing of memes of gifs of politicians one admires, have become part of everyday political discourse” (2021, p. 325). Hills similarly introduces the concept of ‘always-on fandom‘ “as the realm wherein instantaneous access and response becomes not only inexhaustible but also shifts the notion of fandom towards an integral part of daily life” (2017, p. 20). This ‘always-on politics’ uses “the language of fandom: emotive, passionate, and focused on feeling rather than rationality” (Booth et al., 2019, p. 42) such that le Clue argues that “a new, popularized [and politicized] form of online participation and communication is determining a clear shift towards a new normal” (2023, p.5).

It is not a coincidence that Hills also observed how ‘othering and aggression between different fan communities/groups have become more central in the digital age’ (2017:18). Perhaps the lens of political fandom can counter widespread notions of political apathy and disengagement, as less people may be participating in formal politics, more people are seemingly participating in the everyday sharing of political opinions. This seems especially true with anti-fans derisively mocking and hate tweeting their vitriol towards politicians rather than hate watching.[8]

Beyond antagonism seemingly being an increasingly prevalent mode of contemporary politics (and perhaps fandom), we ought to recognize that political fandom extends beyond those social aggregations that adopt politics and politicians as their object of affection (or disaffection). Fandoms are political, too, insofar as they have their own politics. To be clear, this is introducing a new notion of “politics” than has been discussed up to this point. So far, most of the focus has been on politics as it is traditionally understood (the business of governments governing, politicians seeking support, political parties jockeying for public support, etc). This view of largely institutional, formal politics has been termed an “arena” view of politics (examining the politicking that takes place in the traditional ‘arenas’ where power is contested — elections, representative bodies, political parties and interest groups). There is, however, a contrasting view – the “process” based understanding of politics (see Foster et al., 2013, p. 568). This latter view is more concerned with how individuals experience politics in everyday life. It broadens the arena view of public contests beyond formal places for political engagement meant to be representative, public spaces for everyone and instead takes seriously the idea that politics exist everywhere, even in people’s private lives. With interactive media, people now have the tools of participatory culture at their fingertips and can make representative claims for themselves, taking their private concerns public. Communities can be politicized not just because they concern themselves with (formal) politics, but because they can mobilize their collective concerns and adopt political identities, which are in turn assemblages of all the individual fans’ personal political identities. This “process” view of politics resonates with the “personal is political” ethos, concerned with “power relations outside the overarching settings of the state and/or economy and the various ways in which subjects and identities, and consequently citizens, are constructed through everyday social interactions” (Foster et al., 2013, 568). It is less focused on concerns of occupying power and more interested in the construction of identities.

The process view of politics is sometimes colloquially known as “little ‘p’ politics” (compared to the capital-letter ‘P’ associated with the “P”olitics of the “S”tate. This does not focus only on government (and how people are governed), but rather highlights how people often govern themselves, how they negotiate the power relations of everyday life. Another term for this is “micro-politics,” recognizing that power is diffused throughout all our communication, decentralized in our private acts of audience consumption, present in the representations we consume and the symbolic and textual productivity we create. Moving away from the macro field of state towards the micro fields of the social, through one’s individual subjective experience of the world, one always is political, even without being involved in formal politics. In turn, fandom can be political in an arena-mode (influencing political events or politician pronouncements), but its truly politicized character is revealed in the changing modes of political engagement that audiences actively manage in the digital world of networked media.

Any time you’ve encountered the concept of a ‘culture war,’ this is the phenomenon of publics (productive-audiences sharing certain political ideologies) contesting other audience-publics over perceived differences (and different priorities) when it comes to micro-politics. “Culture war” is a politically useful, thoroughly anatagonistic discourse that depends on “the politics of against.” In the 1980s, this battle arose over “textbooks, abortion, prayer in school, affirmative action, and funding of the arts. This war pitted conservative defenders of tradition and morality against liberal defenders of modernity and pluralism” (Foer, 2004, pp. 239-40). More recently, it tends to focus on battles between the alt-rights and its discursively manufactured opponent, i.e. the emotionalized, monstrous-feminine figure of the ‘SJW’ (see Hills, 2018, p. 114). No matter the target, politicized fandoms struggle to communicate different visions of ‘the good life’ and seek dominance for their virtues, beliefs, and practices The label “culture war” tends to flatten political nuances, emphasizing polarized identities and minimizing the fact that everyone has a stake in identity politics (whether from a majoritarian or minority perspective). Similarly, any time you run up against the claim of ‘identity politics,’ “a form of political activity based on the collective experiences and memories of injustices affecting identity-based social groups” (Bliss, 2013, p. 1013), you’re seeing the process model of relational, contingent, and personalized politics at work.[9] Informed by feminist politics, “at the level of representation, gender remains a problem mainly for women; however, at the level of identity, it becomes a problem for everyone” (Foster et al., 2013, p. 582). Even one’s own individual use of social media can be seen as a personal and political project of the self, maintaining an image, disciplining oneself either in the ongoing effort at self-promotion and personal-brand management or simply by selectively promoting a version of one’s self for public consumption (see Hockin-Boyers et al., 2020).

To be clear, the participatory culture of claims-making regarding the politics of identity is greatly indebted to (wait for it – no surprise!…) the interrelated factors of affect and the interactive contemporary media environment. As Landau and Seeley-Jonker point out, “affect is biological and physiological but it is also intertwined with the social and political” (2018, p. 169). Cultural politics built on identity is something one feels, not something that one thinks. Thus, process-oriented participatory political culture is built upon public feelings:

We use the overarching terms of public feeling(s) or affect-emotion to encompass the entire phenomenon and movement of affects and emotions. … Even though public feeling is an umbrella term, it evokes a lineage dating to “the personal is political” feminist mantra and reclamation of emotion. When we refer to public feeling, we put the public and feeling back together again. (Landau and Seeley-Jonker, 2018, p. 170)

And just as “the fanization of politics takes place mainly in the social sphere of what we might label ‘everyday politics’,” (Petersen, 2022, p. 95), so too do we see and experience affect in the everyday. When engaging with identity politics, the informal pluralized, polycentric political space on digital media (where ordinary people share their feelings, experiences and values while navigating everyday relationships) can seem ‘intense.’ But our quotidian affective intensities are not always that extreme:

Affect inquiry easily focuses on instances of peak intensity, on events, yet there’s much to be said for studying the more ambiguous and “flat” aspects of media, too, as this is where much of the politics of everyday life takes shape. So, for example, boredom, a site of affective flatness or even nothingness, plays with excitement and interest, rather than simply being opposite to them. Rather, the issue is one of patterns in affective fabrics that shift in intensity and tone from the heightened to the flat, and many things in-between. (Boler and Davis, 2021, p. 64)

Today, our politicized daily lives takes place in the postmodern marketplace of ideas as we play with identity in “large, decentralized and often leaderless networks facilitated by new communication technologies [and] a form of politics that is based on the participation of all citizens rather than the hierarchical model of traditional politics” (Fenton, 2008, p. 236). Our public feelings take shape not in the agora of Ancient Greece (the original political arena where citizens gathered to adjudicate their concerns), or the abstract public of a national imagined community in political elections, but in the messy public working-out of social bonds and individual identities via participatory media. Participatory culture and political fandom is all about expanding participatory democracy beyond formal voting every four years and creating opportunities for political/civic engagement in all the spaces of our contemporary always-connected lives. Here, it is not just media that are fragmented, but the very idea of mediation also, so that audiences no longer simply consume politics but produce it too. As Fenton argues, “the internet has become home to mediated activity that seeks to raise people’s awareness, to give a voice to those who do not have one, to offer social empowerment, to allow disparate people and causes to organize themselves and form alliances, and ultimately to be used as a tool for social change” (2008, p. 233). While this might sound a tad optimistic with fifteen years of hindsight and toxic fandom percolating in the petri dish of political hope, it nonetheless speaks to the potential for political engagement of contemporary audiences with participatory culture at their disposal.

To suggest that fandoms that don’t focus on politics can be political indicates an erosion of the boundaries between spheres of political and popular communication (Sandvoss, 2013, p. 253).[10] There is a political discourse to the participatory culture of active and interactive fan practices that is sometimes explicit (i.e., when “Democratic Socialist Bernie Sanders appealed to fans of The Hunger Games [and] future White House Chief Stragist Steve Bannon rallied supporters of Donald Trump among the fans of World of Warcraft” (Mueller, 2022, p. 5). Sometimes it is far more implicit. For instance, fans often conceive of themselves as members of quasi-political bodies:

As members of communities, fans are always at world to establish the borders of their invisible townships, and to regulate the rules of inclusion and exclusion that determine access to their communities. As participants in alternative public spheres, fans constantly engage in the negotiation of public opinion and in the (re)evaluation of communal consensus. As members of constituencies, fans establish authorities and hierarchies, develop processes of decision-making, and determine courses of action in order to resolve conflicts with their groups. (Mueller, 2022, p. 10)

Whether it is political commentary directed at a politician or political issue, or fan productions that are somehow political (related to micro-politics or cultural politics, for instance), we can see the prevalence of participatory culture, and this raises numerous very important considerations. First, what is the text with which fans engage? “Like television, music or sports fans, supporters of political figures or parties are committed and regular readers, viewers and listeners to a wide range of mediated text” (Sandvoss, 2021, p. 70), using “mobile and domestic media whose textuality is both more ephemeral and limitless” (Sandvoss, 2021, p. 71). Political fans are active audiences, not just reading multiple discrete texts to inform their viewpoints, but producing and circulating political opinions by participating in a diffused cultural conversation with ever shifting boundaries. “In political fandom … formerly distinct texts, such as news, are intersected with paratexts, including user-created content, and integrated into wider textual fields, in which boundaries around textual formations such as fan objects are drawn by users rather than textual producers.” (Sandvoss, 2019, p. 141). This highlights the need for “forensic fandom” (Reinhard et al., 2022, p. 1159) and is evidence of the fact that “becoming a (political) fan with its associated need to select from the plethora of associated media content across different platforms … is a means of building media literacy” (Sandvoss, 2012, p.79). Second, with whom (or what) are political fans interacting? “The algorithms and recommendation systems used by social media platforms often reinforce existing biases and amplify extreme political views, further entrenching political fandoms and creating an echo chamber effect. This can lead to the spread of misinformation and the further polarization of political discourse” (le Clue, 2023, p.4). Sandvoss sees the dangers of shifting fandom away from popular texts and towards the political realm where selectivity and cultural projection has a greater impact than idiosyncratic readings of popular culture texts (like song lyrics or TV series). Beyond a loss of faith in politicians or the political system, political enthusiasm fuelled by “affective misinvestment” (2013, p. 288) can have even more profound consequences: “Put simply, studying fans and anti-fans in politics shifts the question from which news and information we believe to which news and information we choose to believe” (Sandvoss, 2019, p. 141).[11] Again, our affective investment in “stuff” is likely to be algorithmically augmented which could be especially worrying given that “fandom has long established the relationship between affect, interpretative textual reading and community and belonging—all factors that can drive political discussions at the expense of truth, fact and reason” (Barnes, 2022, p. 53).

Third, what is the nature of that participation? In addition to high levels of engagement and participation, “toxic fan practices are a defining characteristic of political fandom” (le Clue, 2023, p.4).[12] But our most immediate concern should be to distinguish between citizens-as-fans and fans-as-citizens. This chapter has focused on the former, considering “how beliefs drive orientation to a political entity or ideology” and understanding how citizens with “political motivations and beliefs as representing a fandom” (Reinhard et al., 2022, pp. 1153-4). The next chapter will focus on the latter orientation, examining “how fan activism becomes political activism based on the fan community’s shared ideologies” (Reinhard et al., 2022, p. 1153). The next chapter will shift attention to “political fandom as a form of engaged citizenship” (le Clue, 2023, p. 7), and highlight the notion of “civic fandom” to explore “the many groups of fans who have used fandom to develop new public values, envision a different status quo, and find passion, enthusiasm, and commitment for public issues” (Hinck, 2019, p.2). It pivots from fans of politics to fans who are political.

WORK CITED

Allen, Peter, and David S Moon (2023) “‘Huge fan of the drama’: Politics as an object of fandom.” Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, Vol. 0(0) 1–15.

Barnes, Renee (2022) Fandom and Polarization in Online Political Discussion: From Pop Culture to Politics. New York, NY: Springer

Barnes, Renee, and Middlemost, Reneé (2022) “’Hey! Mr Prime Minister!’ – The Simpsons Against the Liberals, Anti-fandom and the ‘Politics of Against’” American Behavioral Scientist, 66(8), 1123–1151.

Bliss, Catherine (2013) “The Marketization of Identity Politics.” Sociology 47(5), 1011–1025, DOI: 10.1177/0038038513495604

Boler, Megan, and Davis, Elizabeth (2021) “Affect, Media, Movement: Interview with Susanna Paasonen and Zizi Papacharissi,” In M. Boler & E. Davis (eds.), Affective Politics of Digital Media: Propaganda by Other Means. New York, NY: Routledge, 53-68.

Booth P, Davisson A, Hess A, et al. (2019) Poaching politics: online communication during the 2016 US presidential election. New York: Peter Lang.

Dean, Johnathan (2017) “Politicising fandom.” The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 19(2), 408–424.

Dean, Jonathan, and Andrews, Phoenix (2021) “Celebritization from Below: Celebrity, Fandom, and Anti-Fandom in British Politics.” New Political Science, 43(3), 320–338 https://doi.org/10.1080/07393148.2021.1957602

Fenton, Natalie (2008) “Mediating hope: New media, politics and resistance.” International Journal of Cultural Studies, 11(2): 230–248 DOI: 10.1177/1367877908089266

Foer, Franklin (2004) How Soccer Explains the World: An unlikely theory of globalizationI. HarperCollins.

Foster Emma, Peter Kerr, Anthony Hopkins, Christopher Byrne and Linda Ahall (2013) “The personal is not political: At least not in the UK’s top politics and IR departments.” The British Journal of Politics & International Relations 15(1): 566–585.

Gray, Jonathan (2019) “How do I dislike thee? Let me count the ways.” In Melissa A. Click (ed.) Anti-Fandom: Dislike and Hate in the Digital Age. New York: New York University Press

Hills, Matt (2018) “An extended Foreword: From fan doxa to toxic fan practices?” Participations: Journal of Audience & Reception Studies, 15(1), 105-126.

—. (2017) “Always-on fandom, waiting and bingeing: Psychoanalysis as an engagement with fans’’infra-ordinary’ experiences.” In The Routledge Companion to Media Fandom. New York, NY: Routledge.

Hinck, Ashley (2019) Politics for the Love of Fandom: Fan-Based Citizenship in a Digital World. LSU Press

Hinck, Ashley, and Davisson, Amber (2020) “Fandom and politics.” Transformative Works and Cultures, Vol. 32, https://journal.transformativeworks.org/index.php/twc/article/view/1973/2433

Hockin-Boyers, Hester, Stacey Pope, and Kimberly Jamie (2020) “Digital pruning: Agency and social media use as a personal political project among female weightlifters in recovery from eating disorders.” New Media & Society, 23(8), https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444820926

Landau, Jamie, and Bethany Keeley-Jonker (2018) “Conductor of public feelings: An affective-emotional rhetorical analysis of Obama’s national eulogy in Tucson.” Quarterly Journal of Speech, 104(2), 166–188.

le Clue, Natalie (2023) “The new normal: Online political fandom and the co-opting of morals.” Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, Vol. 0(0) 1–11 DOI: 10.1177/13548565231190343

Mueller, Hannah (2022) The politics of fandom: Conflicts that divide communities. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc.

Ouellette, Laurie (2012). “Branding the right: The affective economy of Sarah Palin.” Cinema Journal, 51(4), http://www.jstor.org/stable/23253593

Petersen, Line Nybro (2022) Mediatized Fan Play Moods, Modes and Dark Play in Networked Communities. New York, NY: Routledge.

Reinhard, CarrieLynn D., David Stanley, and Linda Howell (2022) “Fans of Q: The Stakes of QAnon’s Functioning as Political Fandom.” American Behavioral Scientist, 66 (8), 1152–1172.

Sandvoss, Cornel. (2019) “The Politics of Against: Political Participation, Anti-Fandom and Populism.” In Anti-Fandom: Dislike and Hate in the Digital Age, ed. Melissa Click, 125–146. NYU Press.

—. (2013) “Toward an understanding of political enthusiasm as media fandom: Blogging, fan productivity and affect in American politics.” Participations: Journal of Audience & Reception Studies, 10(3), 252–296.

—. (2012) “Enthusiasm, trust and its erosion in mediated politics: On fans of Obama and the Liberal Democrats.” European Journal of Communication 27(1), DOI: 10.1177/0267323111435296, 68–81

- The next chapter will focus on 'political fans' which is to say people who activate their membership in fandom to act as members of the wider public, advocating for political, civic change. This chapter focuses on how the world of politics and fandom often operate in parallel fashion. ↵

- See, for example, https://www.elitedaily.com/entertainment/people-upset-the-rock-moana/1536404 ↵

- See, for instance, the controversy over Dwayne Johnson and Oprah's Maui wildfire fund: https://www.usatoday.com/story/entertainment/celebrities/2023/10/09/dwayne-johnson-maui-fundraiser-oprah-winfrey-backlash-response/71116245007/ ↵

- Butterworth, Michael (2022) "Imagining the Citizen-Fan Sport Metaphor in American Politics and Implications for Democratic Culture." in The Routledge Handbook of Sport Fans and Fandom . New York, NY: Routledge, p. 10. ↵

- This overview is deeply indebted to the similar treatment provided by Barnes (2022, pp. 49-9). ↵

- See Reinhard, CarrieLynn D., David Stanley, and Linda Howell (2022) “Fans of Q: The Stakes of QAnon’s Functioning as Political Fandom.” American Behavioral Scientist 66 (8), 1152–1172; Shae Rodriguez, Nathian, and Nadia Goretti (2022) “From Hoops to Hope- Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Political Fandom on Twitter.” International Journal of Communication 16, 65–84. ↵

- A curious instance of this is the fact that the song Ding Dong! The Witch is Dead from The Wizard of Oz entered the UK singles chart at number 2 immediately following Margaret Thatcher’s death, selling 52,605 copies in 2013, seventy-four years after the song was originally featured in the 1939 film. See Dean and Andrews (2021, p. 330) and https://abcnews.go.com/International/margaret-thatchers-death-irreverently-marked-ding-dong-song/story?id=18939709 ↵

- Consider, for example, the January 23, 2023 headline "F-CK Trudeau banner second best selling flag on Amazon Canada" (https://www.westernstandard.news/bc/f-ck-trudeau-banner-second-best-selling-flag-on-amazon-canada/article_82e657b8-9e8a-11ed-ae22-ff8a4cc80df7.html) ↵

- While it might seem we're always debating identity politics today, and is "often associated with the political upheavals of the 1960s, it goes back much further; for instance the Suffragette movement of the 1900s was an earlier form of identity politics" (as John Hartley observed in the 5th edition of Communication, Cultural and Media Studies, p. 157) ↵

- This is a horribly phrased sentence. It's use of the passive voice mangles the intent and subverts its power. The use of a contraction makes it sound better, but is also a bit casual... The paraphrasing makes it also seem like Sandvoss said this, and he didn't! It was me! All in all, it's a bit of a train wreck but I'm leaving it here as a "teaching moment." Try to write a lot more directly and succinctly than this! ↵

- If anyone is interested, I also teach a course on "language and public communication" that should really be called "the language of public manipulation" -- it focuses on varieties of propaganda, misinformation, or just general B.S. designed to get audiences to not just believe certain things, but also interrogates the narrowing and polarization of what we choose to believe as we navigate algorithmic message massaging and negotiate the nature of information and truth itself. ↵

- Chapter 12 on "ugly fandom" devotes more in-depth focus on toxic and harassing behaviour. ↵