65 From Inklings to Interactions: Unraveling the Culture of Division in the Splatoon Twitter Community

Introduction

With the prevalence of information communication technologies, the modern world is constantly interconnected in a way that has never been experienced before. Several institutions have been transformed by these new technologies, and new forms of human interaction using and contextualized by these technologies have emerged as a result. Most notably, the emergence of social media platforms like Twitter, and many others. These developments have had both positive and negative effects in regard to aspects like privacy, socialization, and efficiency. What is definite, however, is that information communication technologies and social media have transformed fandom spaces and allowed fans to meet and interact with one another more easily than ever. Every media in the world today has at least one, if not multiple fandom spaces online associated with it, each with their own unique characteristics. Many of the creators of these media have even encouraged or curated these spaces, and such is the case with Nintendo and their newest installment in the Splatoon video game franchise. Released worldwide on September 9th, 2022, Splatoon 3 took Nintendo Switch owners by storm, selling 3.45 million copies in Japan in just three days (Minotti, 2023). The main way Nintendo drives fan engagement in the Splatoon fandom is through Splatfests, in-game events that occur every other month. These events occur on weekends and are competitive in nature, beginning with a question that asks for the player’s opinion about things that are not necessarily related to the game. In-game characters referred to as idols present the options to answer the query and serve as representatives for a select option, written to be that character’s own opinion within in-game narrative. Players then pick the team that aligns with their opinion and battle all weekend for their idol’s team, with points being assigned depending on the results of individual “turf war” games. The winner is announced within 24 hours of the end of fest. What is important to note here is that Splatoon 3 made significant changes to the Splatfest format, including three idol characters rather than two, creating three teams for fest for the first time in the series’ history as well as a new “turf war” mode where all three teams could battle. For clarity, the most recent Splatfest at the time of writing was based upon the question “What’s your go-to greeting?” and featured Team Handshake, Team Fist Bump, and Team Hug. This Splatfest will serve as a main site of analysis because of its recency and relevance to current fandom discussion. The three team change in the Splatfest formula has intensified the online participation and discussion of Splatoon players worldwide for better or worse and has been the result of much discourse in the fandom, touching on politics, hate, and parasocial relationships, to name a few aspects. While the online Splatoon fandom always experienced some level of division because of the inherently competitive nature of Splatfests, the disturbance of core series features has caused this division to deepen in a way that may not be what Nintendo has intended. The Splatoon 3 Twitter fandom presents a compelling case study for examining the ways in which the emotional investment and attachments of contemporary fans shape a fandom and the participatory culture within them. By conducting an analysis of Splatoon 3 Twitter fandom interactions and discourse through the lens of participatory culture and ordinary fandom theory, it will become evident that Splatoon’s vibrant colour scheme masks a fandom that was designed by its makers to forever be divided.

Ink it Your Way: How the Splatoon Fandom Embodies Participatory Culture

In the vibrant and still-evolving world of the Splatoon 3 Twitter fandom, participatory culture emerges as a dynamic force, fueling creativity, engagement, and community interaction amongst fans of all ages. Because of its colourful and cartoony appearance, Splatoon, alongside many other Nintendo franchises, has been mischaracterized as being only for children. In the era of the internet, this misunderstanding is fast evaporating as many adults and teenagers alike occupy the fandom spaces for these games, with much to say online about their chosen media. The term participatory culture combines the words “participation” and “culture,” and its ideas encompass a variety of communities, not just fandom. As Raymond Williams (2011) wrote, culture is defined as a way of life that encompasses beliefs, values, practices, traditions, social behaviours, arts, and more of a select group of people. As one of the founders of Cultural Studies today, he believed that culture was a complex web of details that could be analyzed to gain a deeper understanding of a group of people. The addition of the word participation here with his definition of culture thus defines participatory culture as a set of practices that bind members of a group together. The term is often used to describe online fandoms such as the Splatoon 3 Twitter fandom. Notable Pop Culture theorist Henry Jenkins (2018) supports this idea of online fandoms as embodying participatory culture, writing in his analysis of the Harry Potter fandom that fandom should be understood “as a form of negotiation that suggests a continuum of possible relations to popular texts, as well as an ongoing process of negotiation with changing meanings that reflect changing times” (p. 16). Participation is a continuum (Bury, 2018): a spectrum of activities that range from low to high fandom involvement, and the range of these activities can be seen in the Splatoon 3 Twitter fandom (Figure 1 & 2). Produsers and prosumers (O’Boyle, pp. 154 & 160), combinations of the words “producer,” “consumer,” and “user,” make up much of online fandom spaces. These are fans with significant community value within their chosen fandom, online users who produce new fandom content for others to consume while consuming content themselves. Low-range activities in the Splatoon 3 fandom are mirrors of those in other fandoms: engaging with content creators who are part of the fandom, responding to community opinion polls, sharing and “liking” Splatoon artwork or other related content, and more. High-range activities in the Splatoon 3 fandom are also like those in other fandoms: Writing fanfiction, creating fan artworks or zines, and fan-hosted game tournaments or events. Beyond regular fandom activities, Splatfests are unique to Splatoon in how they epitomize participatory culture. They provide incentive for further gameplay and solicit the opinions of players on various themes, some of these themes having in-game implications within the game’s ongoing narrative. For example, the final Splatfest of Splatoon 1 and Splatoon 2’s “Final Fest: Splatocalypse” had player-determined results that directly shaped the narrative development of their successors. It is likely that Splatoon 3’s final Splatfest will follow this trend, once again asking for player contribution to the narrative of the next installment in the series. These collective endeavors highlight how the Splatoon 3 fandom transcends traditional boundaries of consumerism, transforming players into co-weavers of the ongoing tapestry that is the Splatoon series. Fans from all levels of the participation spectrum can achieve high value within the Splatoon series just by playing the game, showcasing again how the emergence of online technologies is addressing and potentially even equalizing power inequalities (Tombleson, & Wolf, pp. 14). Nintendo has capitalized upon information communication technologies and their democratizing power by designing the Splatoon series in this way. Consistent game updates keep players engaged and participating in the online fandom, and Splatfests keep competition and anticipation alive, further driving produser and prosumer activity. However, what was intended by Nintendo to be healthy competition has led to much discourse and division within the Splatoon 3 Twitter fandom. This division has resulted in much debate about the health of Splatfests (Figure 3). These debates touch upon the identity politics of Splatoon players, bringing to the fandom table issues of racism and favouritism within the Splatoon 3 Twitter community in regard to Splatfest results.

Ideological Ink: Politics and Competition Within the Splatoon Fandom

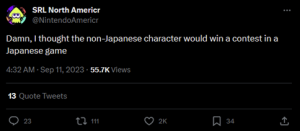

Just as every community in history before it, the Splatoon 3 Twitter fandom possesses division and can never be fully unified on certain subjects. Disagreement is natural and should be anticipated, especially in video game communities where competition is intense. But not every media can boast that its creators share responsibility for the seeding of divisions, like Splatoon 3 can with its Splatfests. Competition lends itself well to the creation of anti-fans or anti-fandom within a fandom, manifesting itself in what is referred to as competitive anti-fandom. Coined by Jonathan Gray (2019, p. 26), competitive anti-fandom refers to when one object becomes beloved by members of a fandom and disliked by others. He uses sports rivalries as an example, where teams must defeat each other to advance (p. 27), inherently creating competition. Splatfests in Splatoon three are like sports in this sense: players must select one of three teams and play to defeat the other two. The player’s own team becomes the beloved object that they must defend, and the opposing enemy teams become disliked objects. The teams are not the only objects at play here, however. The other notable objects that players of Splatoon 3 are committed to defending or disliking are the game’s idol characters, otherwise known as Deep Cut. Deep Cut is a fictional, in-game musical group consisting of three members: Shiver, Frye, and Big Man, an Octoling, an Inkling, and an anthropomorphic Manta ray, respectively. These characters are seen for the first time when the player launches the game, serving as the voice of the game’s developers when updates occur as well as being distinct members of a musical group with their own voices and personalities. They announce the beginning of new Splatfests with unique and character-driven dialogue, with each team representing the opinion of a member of Deep Cut. During the event, players can take pictures of and with the idols after winning a high-value battle for their team, with their player names being announced for everyone who is currently online to see. When Splatfests end, Deep Cut announce the results with more special dialogue and directly congratulate players who played for their team. Deep Cut are not the first of their kind, the successors of two other idol groups from the two Splatoon series installments. They represent the continuation of one of Splatoon’s core elements: 2.5-dimensional culture, which is a space between the two-dimensional spaces of human imagination and the three-dimensional spaces of reality (Sugawa-Shimada, 2020, p. 2). 2.5-D culture is prevalent in Japan, revolving around character-oriented consumption by fans. Another example of a character who was born from this 2.5-D culture is Crypton Future Media’s Hatsune Miku, a virtual idol with the ability to sing, dance, and interact with fans in the real world in whichever ways they choose. Splatoon’s idols are fictional, but have real-life performances hosted by Nintendo and interactions with fans using virtual elements. This and their centering of the narrative of each game makes them important objects in the fandom, arguably more important than the teams they are representing, with many fans even stating online that they want to fight for the idol, rather than feeling aligned with the theme (Figure 9). This culture of idol obsession is expected and was deliberately constructed by Nintendo to drive fan engagement through competition. Fans can spend the game’s lifespan constantly putting their beloved objects against those of others, distancing themselves from their losses and feeling increased ego as well as deeper connections with their idols upon victory (Downs & Shyam, 2011). However, this culture is also responsible for debate and division about the health of Splatfests in Splatoon 3. The most prevalent discourse in fandom is about the idols themselves, namely its members that are Octoling and Inkling like the playerbase themselves: Shiver and Frye. Of the 11 Splatfests that have taken place in Splatoon 3 since its release, Shiver’s team was victorious in 8, with 6 of those wins being consecutive. The victor of the most recent Splatfest was also Shiver, where she represented Team Handshake. In comparison, her bandmate Frye has had 1 Splatfest victory overall. Winstreaks to this extent had never been seen before in Splatoon, and Splatfest discourse reached, and is continuing to reach an all-time high. Fans took to Twitter once again to lament that Splatfests had become unfun events with predictable outcomes, posting memes about their dislike for Shiver, posting in support of Frye, and making nostalgic callbacks to previous Splatoon games (Figure 3-6). The competitive anti-fandom of Splatoon 3 has splintered into a disappointed anti-fandom, defined by Gray as fans who love one portion of their chosen text, but find other aspects of it to be repellant (2019, p. 30). Though much of Splatoon’s appeal is in its Splatfests and its characters, these two aspects have become a source of significant unrest in the Twitter fandom. Sizeable anti-fan sentiment and hate has been directed towards Shiver’s character, with backlash from fans of Shiver. Accusations of favouritism or rigging have been thrown at Nintendo, with others even hinting at Japanese xenophobia, homophobia, or racism as the cause for Frye’s loss streak (Figure 7 & 8). Splatoon is most popular in Japan, and Splatoon 3’s Splatfests are the first in the series to be international, counting votes and gameplay from fans across the world collectively. Fans argue that Shiver’s Japanese-inspired design is winning more favour than Frye’s Indian-inspired one because of racism towards darker-skinned characters, and that they are at the mercy of a Japanese majority who will continue to propel Shiver’s teams to victory (Figure 11). Rather than disengage with Splatfests or Splatoon 3 as a whole because of their dissatisfaction, fans are having negatively charged relationships with the idol who is their disliked object. Just as consumers choose to participate in anti-fan communities for newly disliked social media influencers (Mardon et al., 2023), Splatoon fans are choosing to participate in anti-fan community behaviour towards fictional characters. Although Nintendo may not have intended for the division to occur to this degree, their Splatfest system is responsible. The unrest in the Splatoon 3 Twitter fandom was inevitable because of Nintendo’s injection of idol culture and celebrity obsession into a video game.

Starry-Eyed Squids: Celebrity Obsession in The Splatoon Fandom

In the Splatoon 3 fandom, the allure of celebrity and the development of parasocial relationships intertwine, creating an intriguing facet of fan engagement. In Splatoon, characters have always forged attachments and emotional connections to the idol characters, and Splatoon 3 is no exception. Fans invest heavily in the virtual personas of Shiver, Frye, and Big Man, celebrating their victories and developments, while empathizing with their struggles. This serves to foster a sense of closeness that is akin to, if not equal to, real-life celebrity admiration. This relationship is one of parasociality, a one-sided love that can never be more because of the fictional nature of the characters on the receiving end. However, celebrities’ communication with fans through social media gives the greater impression of two-way communication and serves to create new expectations of intimacy and deepen fan relationships regardless (Click et. al, 2017, p. 608). In this case, the “social media” in question is Deep Cut’s announcement stage and their direct acknowledgement of fans in-game. The members of the group also acknowledge players in the world of the game, able to be seen waving at the player if looked at in their studio. This once again ties into the intended 2.5-D culture (Sugawa-Shimada, 2020, p. 2) of Splatoon, feeding the player’s idol obsessions. As further evidence of fan’s ties with the in-game idols, much of the content being made in the fandom is centered around the idols. Fans create polls asking others who their favourite Splatoon idol of choice is, share artwork of the idols, create fanfiction about them, and gush online about their attractiveness (Figure 10). Many go as far as to describe themselves as “simps” of the characters, which is African American slang that describes a man who invests too much time in women who are not interested (María, 2021). This idolization culture of memes around the idols is typical celebrity fan behaviour: fans create and circulate memes to develop a sense of closeness with someone who is famous (Nielsen & Nititham, 2022, p. 160). While parasocial relationships in fan communities carry a sense of closeness and engagement, often resulting in impactful fanworks and discussion, they also have downsides that are being seen in real time. Excessive investment in one-sided connections with the Splatoon 3 idols has caused skewed expectations for the characters regarding Splatfest victories and popularity. The intensity of these parasocial relationships have contributed to heightened emotions within the fandom, which has led to conflict when the expectation for the idol, in this case their Splatfest victory, has not been met. These connections can offer solace and a sense of belonging, particularly when fans gather to discuss their favourite idol or favourite songs by said idols in the series. But the inherent overemphasis on idol-fan relationships in Splatoon by Nintendo can and has led to emotional distress, with some fans of Shiver even receiving threats for their love of the character (Figure 12). The celebrity and idol obsession in Splatoon is a core feature of the series, but it is also the main source of much of the discourse and division within its fandom. This division is manufactured by the creators of the series themselves, and the consequences of this design choice are continuing to expand and develop in real time.

Conclusion

The transformative influence of information communication technologies has undeniably redefined the contours of fan engagement within the Splatoon 3 community. The amalgamation of interactive gaming experiences, social media platforms, and the evolution of participatory events like Splatfests forms the basis of this new intertwined relationship between technology and fandom culture. However, this amalgamation has revealed a duality within the Splatoon 3 Twitter fandom. While these developments have helped to foster unprecedented levels of interaction and creative expression amongst fans of the series, they have also exposed fractures within the Splatoon community’s fabric. The recent changes in the Splatfest formula effected in Splatoon 3, most notably its shift to a three-team competition from two, were intended to intensify fan participation but have inadvertently created an even deeper division. Previously envisioned as a central point of celebratory camaraderie and shared experiences, the Splatoon 3 Twitter fandom is undergoing a transformation into a mess of conflicting ideologies and emotional investments. This points to the inherent challenges of contemporary fan cultures, especially with creator interference, as well as emphasizing the need for delicate interplay between fan attachments, technological advancements, and the fostering of a cohesive fan environment. Nintendo can and should learn from the Splatfests of Splatoon 3 and their resulting fandom discourse to help cultivate a better space for the next installment. While the competitive and idolatry aspects of Splatoon 3 and its Splatfests will likely always remain a core element, representing much of the series’ appeal, they can be improved on in ways that will mitigate the formation of disappointed anti-fandoms within the fandom. The Splatoon 3 Twitter community serves as a multifaceted case study that illuminates the intricate dynamics of participatory culture within online fan spaces and advocates for improved producer-consumer relationships, particularly within contemporary gaming communities. It also serves as an example of what happens within a fandom when the creator of their chosen text makes decisions deliberately designed to cause discourse and division. Not only is Nintendo responsible for the fractures within the Splatoon 3 fandom, the unintended consequences of their innovations and restructuring efforts have also inadvertently deepened the existing fault lines within this vibrant and passionate community.

Appendix

Figure 1: One Splatoon 3 player’s quote retweet of another player’s tweet, using imagery of said player being aimed at by the sights of the entirety of the enemy team as a meme to drive community engagement.

Figure 2: A member of the Splatoon 3 Twitter fandom calling for the participation of artists in the fandom who have created artwork for the game.

Figure 3: A Splatoon 3 player’s tweet featuring a screenshot of Splatoon 2 Splatfest results. They are responding to the results of the most recent Splatfest in Splatoon 3 at the time of writing, wishing for the return of “good” Splatfest results.

Figure 4: A Splatoon 3 player’s tweet featuring their own original artwork in response to recent Splatfest results. It features two members of in-game musical group Deep Cut, announcing a new dish at a restaurant that appears to be made from the third member’s tentacles.

Figure 5: A Splatoon 3 player’s tweet emulating the would-be Twitter account of Frye, a member of Deep Cut. They are hoping that her team will win the upcoming FrostyFest.

Figure 6: A Splatoon 3 player’s tweet lamenting that Splatfests are no longer enjoyable because of favouritism within the fandom.

Figure 7: A Splatoon 3 player’s tweet discussing racism within the fandom, featuring an image of an in-game idol character.

Figure 8: A Splatoon 3 player’s tweet discussing homophobia within the fandom.

Figure 9: A screenshot of the Twitter search showcasing fan loyalty to an idol in Splatoon 3, with fans stating they will fight for her.

Figure 10: A screenshot of the Twitter search results showcasing fan reactions to an idol’s new look in Splatoon 3.

Figure 11: A Splatoon 3 player’s commentary on the Splatfest discourse.

Figure 12: Splatoon 3 players discussing the death threats they and their mutual followers have received for being a fan of Shiver.

References

[@aceofdarts68]. (2023, August 11). What are some splatoon opinions that’ll get you like this?

[@Barbie_pinke]. (2023, September 11). If I see one more white Splatoon fan dismiss the racism issue in the community I’m going to say something. [Tweet]. Twitter. https://twitter.com/Barbie_pinke/status/1701366074447688069

[@booparoos]. (2023, March 5). guys i didnt know the homophobic straight splatoon fans were real i thought you were all kidding. [Tweet]. Twitter. https://twitter.com/booparoos/status/1632483432457543681

[@kaasiand]. (2023, September 11). aftermath. [Tweet]. Twitter. https://twitter.com/kaasiand/status/1701287707379421190

[@Maskavado]. (2023, November 19). getting tired of this splatfest cycle… [Tweet]. Twitter. https://twitter.com/Maskavado/status/1726450843405451584

[@NintendoAmericr]. (2023, September 11). Damn, I thought the non-Japanese character would win a contest in a Japanese game.

[@yggdrasilsaltar]. (2023, November 19). we need to go back to when splatfest results were good. [Tweet]. Twitter. https://twitter.com/yggdrasilsaltar/status/1726425155948167205

[@Zimmly]. (2023, September 10). Listen, I like Shiver, but I won’t lie, Splatfests are getting less fun or motivating to participate in. [Tweet]. Twitter. https://twitter.com/Zimmly/status/1701070083194585452

[Tweet]. Twitter. https://twitter.com/NintendoAmericr/status/1701151830183424334

Bury, R. (2018). We’re not there: Fans, Fan Studies, and the Participatory Continuum. In The Routledge Companion to Media Fandom (1st ed., pp. 123–131). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315637518-16

Click, M. A., Lee, H., & Holladay, H. W. (2017). ‘You’re born to be brave’: Lady Gaga’s use of social media to inspire fans’ political awareness. International Journal of Cultural Studies, 20(6), 603-619. https://doi-org.proxy.library.brocku.ca/10.1177/1367877915595893

Downs, E., & Shyam Sundar, S. (2011). “We won” vs. “They lost”: Exploring ego-enhancement and self-preservation tendencies in the context of video game play. Entertainment Computing, 2(1), 23–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.entcom.2011.03.012

Gray, J. (2019). How Do I Dislike Thee? Let Me Count The Ways. In Anti-fandom : dislike and hate in the digital age. (pp. 25-41). New York University Press.

Hills, M. (2017). Always-on fandom, Waiting and Bingeing. Taylor and Francis. In The Routledge Companion to Media Fandom. (pp. 18-26). Taylor and Francis.

Jenkins, H. (2018). Fandom, Negotiation, and Participatory Culture. In A Companion to Media Fandom and Fan Studies (pp. 11–26). John Wiley & Sons, Inc. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119237211.ch1

Mardon, R., Cocker, H., & Daunt, K. (2023). When parasocial relationships turn sour: social media influencers, eroded and exploitative intimacies, and anti-fan communities. Journal of Marketing Management, 39(11–12), 1132–1162. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2022.2149609

María, A. (2021). Here’s why people are calling each other “simps” online. The Daily Dot. https://www.dailydot.com/unclick/what-does-simp-mean-meme/

Minotti, M. (2023). Splatoon 3 sells a massive 3.45 million copies in Japan in first three days. VentureBeat. https://venturebeat.com/games/splatoon-3-sells-a-massive-3-45-million-copies-in-japan-in-first-three-days/

Nielsen, D., & Nititham, D. S. (2022). Celebrity memes, audioshop, and participatory fan culture: a case study on Keanu Reeves memes. Celebrity Studies, 13(2), 159–170. https://doi.org/10.1080/19392397.2022.2063397

O’Boyle, N. (2022). Produsers: New Media Audiences and the Paradoxes of Participatory Culture. In Communication Theory for Humans (pp. 153–181). Springer International Publishing AG. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-02450-4_7

Sugawa-Shimada, A. (2020). Emerging “2.5-dimensional” Culture: Character-oriented Cultural Practices and “Community of Preferences” as a New Fandom in Japan and Beyond. Mechademia, 12(2), 124–139. https://doi.org/10.5749/mech.12.2.0124

Tombleson, B., & Wolf, K. (2017). Rethinking the circuit of culture: How participatory culture has transformed cross-cultural communication. Public Relations Review, 43(1), 14–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2016.10.017

Tweet]. Twitter. https://twitter.com/aceofdarts68/status/1690007036539400193

Twitter. (2023, December 3). Twitter Search: Fight For Frye. [Digital Image]. Twitter. https://twitter.com/search?q=fight%20for%20frye&src=typed_query

Twitter. (2023, December 8). Twitter Search: Shiver Death Threats. [Digital Image]. Twitter. https://twitter.com/search?q=shiver%20death%20threats&src=typed_query

Twitter. (2023, December 3). Twitter Search: Shiver Simp. [Digital Image]. Twitter. https://twitter.com/search?q=shiver%20simp&src=typed_query&f=top

Williams, R. (2011). Culture is Ordinary. In The Everyday Life Reader. (pp. 91–100). London: Routledge.