85 Country Music Sucks, But Does it Actually?

An Auto-Ethnography of Anti-Fandom Affiliation Turned Fandom

mf20al

Country Music Sucks, But Does it Actually?

An Auto-Ethnography of Anti-Fandom Affiliation Turned Fandom

Ella Ferrell – Brock University – COMM 3P18: Audience Studies – December 5, 2023

I’ve always hated country music; and when I say hated, I mean fully, actively, wholeheartedly hated country music. It was a huge part of my music identity, let alone my full identity. Music has always meant so much to me. Growing up I gained my music taste and knowledge from my parents and started exploring new music as soon as I could. This led to the consumption of a wide range of music genres in my created playlists; however, no country was to be found.

This auto-ethnography is a dive into how I placed myself in the anti-fandom of country music and my reasoning for that. I will look at how my environment, identity, and political placement all enforced my anti-fandom participation. I will then move into how and when my fandom status started to change and my position moved from anti-fandom to a slight consumer; the emphasis being on a consumer rather than a fan, yet on being a fan at the same time. Lastly, I will evaluate where I see my fandom status going in the future and how these factors can not be predicted.

What is an Anti-Fan?

First, I want to evaluate what an anti-fan is. Asking the question of what is an anti-fan is equivalent to asking the question: “What is the opposite of fandom?”, with the answer being: “Disinterest. Dislike. Disgust. Hate.” (Click, 2019, pg. 1). This is a good introduction to what it means to be more than a non-fan, to be more than a bystander, to actually interact in a hateful manner. This is because anti-fans “love to hate” (Click, 2019, pg. 1), they hate certain media, certain subcultures, and certain content; they have an active dislike of something and they decide to share this with others.

We see this above with Phy. They very clearly hate country music and decided to share this via Twitter (Phy, 2023).

Then with David Halley. They believe country music is not a valid music genre and shared this via Facebook (Halley, 2023).

Anti-fans love to participate in a collective interaction, sharing this experience with someone else. “Anti-fan is the new fan” (Click, 2019, pg. 17); a fan of the community they created, a fan of the connection, a fan of the hate-driven content created.

The fan content has been memes; a few examples of this memeification, shared by Mike Primavera, give insight into how country music anti-fans feel and what methods they use to make fun of their own position as well (2023).

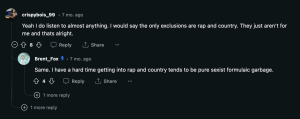

Alongside these posts, we see groups that “anti-fan [groups] are united through dislike” (Barnes & Middlemost, 2022). A post seen on Reddit shows a quick back and forth from two country music haters and examples a moment of bonding (Crispybois_99 & Fox, 2023):

There is a sense of justification in conversation. People trying to prove their point in order to hold onto their anti-fandom community. They do this as a form of “defense against perceived threats to one’s fan affiliation.” (Barnes & Middlemost, 2022), because the other side of the argument speaks like this (Penumbra, AZSuburbs, & Lyssa, 2023):

Each group is trying to maintain their sense of community, their interests, and their sense of self. “The more [these] signs circulate, the more effective they become”, causing the emotions of fans and anti-fans to be held secure within their separate social hierarchy (Click, 2019, pg. 13). These expressions are “tools for creating unity and for maintaining community borders” (Click, 2019, pg. 15), which can be seen in both fandom and anti-fandom proving that “anti-fans can be just as engaged, committed, and beneficial as fans” (Pyo, 2023).

When I was an Anti-Fan

Now that I’ve established what it means to be an anti-fan, I want to outline my experience within the country music anti-fandom. My hate for country music started in my childhood, molded by my parents. They started and reinforced my hate for country music with their active hate. They never played country radio stations, they showed disgust when country music would play in public, criticized their friends for going to country music concerts, never played any in the house while cooking, eating dinner, etc. Growing up, I listened to alternative, rock, indie, radio pop, and folk; “considering folk’s traditional alliance with the left” (Willman, 2005, pg. 11). I liked folk music even though it was borderline country, but refused to listen to anything actually labeled country. Let’s say I heard a song on the radio or online and liked it, if I found out that it was country I would skip it, turn it off, or change the station. Part of me still didn’t realize why I hated it so much. I was the girl who said, “‘Anything but country’” (Arnold, 2014, pg. 23) when asked what type of music she liked. Arnold outlines these wonders through the use of a few questions: “Why is ‘Anything but country’ such a common refrain? Who invokes it? What does it mean? And is it really about music?” (2014, pg. 23). The last question in this quote really resonates with me and my past. Was it really about the music? Because I think now I can sit here and say no; it had barely anything to do with the actual music and so much to do with the artists, the political views, and the people who liked the music. Overall, the culture, identity, and lifestyle were not for me.

This reinforcement of music taste from my parents goes hand and hand with the reinforcement of political views. I grew up in a very liberal household, my parents have leftist views and I became a slight product of my environment. My morals were shaped by my parents but I recognize now that I am not reliant on them for my political views. They introduced me to politics with their views, but within my education, I was able to maintain my views in my own way. I am emphasizing that my views are my views, regardless of how I was raised; however, most of my views and my parents’ views remain the same. This started my position within a political fandom. I started to become passionate about legal, humanity, and discriminatory issues within society. I joined the “tendency [to] fandomize political supporters” (Moon, 2018, pg. 1) yet it was actually about the fandomization of the community. Having my political views being part of my identity, being able to relate to the people I surround myself with, and participating in practices that guarantee I can maintain my political views and stay true to them. This meant that I could not participate in country music because of what comes with that.

My political fandom was a reason for not respecting certain artists who created music and the people who listened to it. This behaviour was an example that I can now see as “further investigations into citizens’ perceptions and behaviors as related to the political fandom.” (Moon, 2018, pg. 2). My behaviour was justified based on my perception of country music, country artists, country listeners and how these actions and people were not on the same page as me in terms of morals and politics. It was then easy to deem country music as politically conservative based on how there has “always been politically [biased] songs in country music’” (Willman, 2005, pg. 3). Even with as much as we were taught to not stereotype people, I confess to being prejudiced against those who make and listen to country music because “when it comes to country conservatism, ‘the stereotype is very well documented, and the perception is pretty much the reality’…” (Willman, 2005, pg. 8). My political views were threatened by those who listen to country music and these stereotypes were reinforced by the artists and the people I knew who listened to the music.

The artists of country music make it very easy to be an anti-fan. Three bold examples are Morgan Wallan, Jason Aldean, and Jimmie Allen. Morgan Wallen is a country singer who has gained a lot of popularity recently; with a huge following and fan base. However, Wallen was “heard using the N-word to address his friend as they returned to Morgan’s house after a night out in Nashville.” (Lane, 2023). This was from February of 2021, a time when people should have understood why we don’t say racial slurs. Wallan, of course, put out an apology video soon after addressing his regret, but you can see in the original video that he had no remorse. He regrets it because he got caught. That is a type of person that I find hard to respect, so when they release music, it is very compelling to not engage whatsoever. Then we see Jason Aldean, another very popular country singer who has gained a large following. A couple of headlines about Aldean were about him “[wearing] a Confederate flag shirt onstage” and being “a proud conservative and Donald Trump supporter.” (Grow, 2023). Lastly, we see Jimmie Allen. A country musician who “is facing another sexual assault lawsuit” (Blistein, 2023). This example is less about politics and more about country singers proving themselves to be horrible people.

These are, again, reasons for me to be fully against a person’s music and them as a person. The majority of the time, I am understanding of other people’s beliefs, choices, political views, and religious affiliations. However, violating basic morality and human rights is something I can not, and will not, support. People who have a lack of respect, who wear Confederate merchandise, who support a man like Donald Trump, and who harmfully disrespect women, are people who I can not engage with. It’s less about politics at that point, and more about respect, and I do not respect that side of country music and can not validate with my support.

In addition to not respecting the artists, I had trouble respecting the people who listened to the music. In high school especially, I noticed there was a correlation between the music people listened to and their presumed political views. The people, at least in my hometown, who openly listened to country music agreed with politics that I did not, so I did not talk to or have friendships with those individuals. Specifically because if they were anything like the artists mentioned above, I did not want to be associated with them and I expressed a “disgust [that was] permeated by power relations” (Click, 2019, pg. 14). I thought I was better than them, on a musical, moral, and human being basis. Not liking country music in my hometown puts you in a minority, but a minority I’d rather be part of than associated with the cruelness these people shared.

After hating country music up until I started university, I, of course, brought my dislike into my post-secondary life. It turned out to be a bonding point for many of my new friends. Music was important to me and hearing that my new friends liked the music I liked was so exciting. Then on top of that, they also voiced how they disliked country music. I was floored, I was so happy that I shared this experience, shared this anti-fandom, with these people I just met. It put us on the same level, the hierarchy that I created based on my political affiliation, was satisfied by these answers.

After first year and into second year, I noticed a shift in the music my friends were listening to. We met some new people who happened to like country music and my friends started to bond with our new friends over this. My close friends then suddenly started listening to the country music our new friends liked. They started to play it in our apartment and talk about it amongst themselves. I felt betrayed; one of the deep-rooted bonding points I had with my friends was dismantled so quickly. I took this personally and was genuinely heartbroken. Looking back, it is so interesting to see just how much it upset me. Since then, once all my friends started to enjoy the music, I felt pressured to like it. I fell into the fifth antecedent of consumer fandom: subjective norms, which is “defined in a broader scope as the social pressure from others including friends and family, any significant others as well as fans of the same fandom.” (Hao, 2020). I was forcefully exposed when all my friends started playing the music when I was around, I was resistant but had no choice.

I was still very against the music, but would tolerate it when I had to. This led to a cottage trip over the summer that changed my perspective. I was introduced to songs I had never heard before and artists that I didn’t even know existed. After the cottage trip, I walked away with a little more twang in my step and would listen to the songs I heard to be able to relive the memories of the trip. It reminded me of the amazing time I had as I can now re-experience those memories. I felt guilty for liking the music, but as I had more conversations about the songs and the artists, I realized that these artists were good people with good intentions, unlike those mentioned above, and it started to change my view. My friends, my close friends, now like country music. People I share space and morals with, like country music; maybe it’s not all bad.

Learning to Accept

Not all country singers are bad. The music is inherently sexist, racist, and homophobic, and the examples earlier in this paper show the bad, but that does not mean all artists agree with those views. The people who indulge in the music created by progressive artists aren’t automatically bad people. Examples of progressive country artists are Zach Bryan, Thomas Rhett, and Tyler Childers. Country artist Zach Bryan “showed solidarity with the transgender community by publicly criticizing his fellow musicians for their intolerance of transgender people.” (Wiggins, 2023). This was regarding the Dylan Mulvaney and Bud Light partnership. Bryan made sure to show his support for the transgender community. We see Thomas Rhett, another country artist, and his wife, “sharing messages of support for [the] Black Lives Matter movement” (Norris, 2020). They share that they stand with the Black community and all those hurt by the tragedy of George Floyd, and all other families who suffer from losing loved ones in similar ways (Norris, 2020). Then there’s Tyler Childers. A modern country artist with “a powerful protest song and a video message aimed at his ‘white rural listeners’ expressing solidarity with the Black Lives Matter movement.” (Havighurst, 2020). Childers also shared “LGBTQ representation in [the music video for] ‘In Your Love’” by having a gay relationship share the story of the song (Hudak, 2023). Alongside being outspoken about BLM and LGBTQ matters, Childers is also openly supportive of democratic politicians (Horn & Duvall, 2023).

Seeing the good within the country music genre is a reminder to see the bad in every other genre. The good in country music goes hand and hand with the fact that all musical artists do bad things, not just country ones. If I am going to boycott all of country music because of a few bad apples, then, with that logic, I also need to boycott alternative, pop, and folk music for their bad apples. But I’m not going to do that, if I did, I’d have absolutely no music to listen to because no genre is perfect. A few bad apples from other genres of music are Rex Orange County, Winston Marshall, and Jacob Hoggard. Earlier this year, Rex Orange County, an indie/alternative singer, had a legal scandal. The singer had six sexual assault charges against him. The “charges against him [were] dropped, shortly before he was due to stand trial.” (Youngs, 2022). Regardless of whether these allegations are true or not, they instilled a sense of distrust and discomfort in the artist for his fans. The next example is actions by Winston Marshall, a former member of the folk-rock band Mumford & Sons. Marshall “faced online backlash in March 2021 after tweeting praise for a book by the controversial US journalist Andy Ngo titled Unmasked: Inside Antifa’s Radical Plan To Destroy Democracy.” (Jones, 2022). His political views pressured him to leave the band, even after Marcus Mumford, lead singer of the band, “begged him not to leave” and believed that people with differing political beliefs “can disagree and [still] work together.” (Jones, 2022). A third example is when Jacob Hoggard, “former lead singer of [pop] band Hedley, was found guilty of sexual assault causing bodily harm in June [2022] after raping an Ottawa woman in 2016.” (Benchetrit, 2022). These reminders are eye-opening to the reality of the music industry as a whole. Now, we can not compare sexual assault allegations with differing political views, but we can see that when grouped together, they show examples of the harmful negativity that is all around us.

Concluding Thoughts

Coming to the end of this auto-ethnography, I hope to have properly explored my position and experience within the country music anti-fandom. I was part of the community for family, political, and personal reasons. This was reinforced by those in the media and those around me who had a lifestyle based on country music that I did not agree with. I grew out of anti-fandom because of the new people who were around me and learned more about what the music industry really is and how often we see bad people in all genres. Even with all the negativity, I was able to find positivity within the genre and be able to relive exciting memories because of the music I was introduced to. I became a consumer, not because I was a fan, but because it fit into my life. It made sense for me to listen to the music and it was a natural transition because of my friends. When I first started writing this paper, I thought I was stuck between a fan and an anti-fan. However, after researching the good that many country artists do and being able to see my political views in relation to their work, it makes me want to be a fan, and it makes me want to share my support. I do not consider myself a fan of country music, I consider myself a fan of certain country artists. I feel as though I am in a neutral position where I still carry an active dislike of certain people and the fandoms that follow them, but I can enjoy the music of those whom I respect. I will continue to remind myself that liking country music does not change who I am as a person, and I can still maintain my values while liking progressive artists. Even though they are part of a historically negative genre, that doesn’t mean they can’t be the good aspects within.

In the future, I hope to not be embarrassed to consider myself a fan. Doing more research and being a more ethical consumer will help me to fully enjoy the music. I may even see myself going to a concert, or purchasing merchandise related to the artist. I will continue to not glorify artists as well, in any genre, because there are individuals all around who deserve the anti-fandom following they have. In the end, I fear I have betrayed part of my upbringing by associating with country music to a certain extent, but as I move forward, this growth was about finding community and finding a new part of my music identity; and that is not something I can not resent myself for.

References

Arnold, D. (2014). Rednecks, queers, and country music [Review of Rednecks, queers, and country music]. Choice, 52(2), 303-. American Library Association dba CHOICE.

Barnes, R., & Middlemost, R. (2022). “Hey! Mr Prime Minister!”: The Simpsons Against the Liberals, Anti-fandom and the “Politics of Against.” The American Behavioral Scientist (Beverly Hills), 66(8), 1123–1151. https://doi.org/10.1177/00027642211042292

Benchetrit, J. (2022, October 20). Former Hedley frontman Jacob Hoggard sentenced to 5 years in prison for sexual assault: RCI. Radio-Canada. https://ici.radio-canada.ca/rci/en/news/1926221/former-hedley-frontman-jacob-hoggard-sentenced-to-5-years-in-prison-for-sexual-assault

Blistein, J. (2023, June 9). Jimmie Allen hit with second sexual assault lawsuit by woman claiming he filmed her without consent. Rolling Stone. https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-country/jimmie-allen-second-sexual-assault-lawsuit-1234767916/amp/

Click, M. A. (Ed.). (2019). Anti-fandom : dislike and hate in the digital age. New York University Press.

Crispybois_99, & Fox, B. (2023, May 5). Anything but country. Reddit. https://www.reddit.com/r/dankmemes/comments/1394npa/anything_but_country/

Grow, K. (2023, July 20). A timeline of Jason Aldean’s controversies: Blackface and Confederate flags. Rolling Stone. https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-features/jason-aldean-controversy-timeline-try-that-in-a-small-town-1234791576/

Halley, D. (2023, May 21). I Hate Country Music. Facebook. https://www.facebook.com/groups/480185765495354/

Hao, A. (2020). Understanding Consumer Fandom: Literature Review and Conceptual Framework. In Handbook of Research on the Impact of Fandom in Society and Consumerism (pp. 18–37). https://www-igi-global-com.proxy.library.brocku.ca/gateway/chapter/full-text-html/237683

Havighurst, C. (2020, September 21). Tyler Childers goes there, challenging fans on black lives matter and the confederate flag. WMOT. https://www.wmot.org/roots-radio-news/2020-09-21/tyler-childers-goes-there-challenging-fans-on-black-lives-matter-and-the-confederate-flag

Horn, A., & Duvall, T. (2023, November 30). Country music star, Ky. native Tyler Childers to Perform at Beshear inauguration. Herald Leader. https://www.kentucky.com/news/politics-government/article282511613.html

Hudak, J. (2023, August 1). Why Tyler Childers put a gay love story in his new video. Rolling Stone. https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-features/tyler-childers-in-your-love-video-gay-cast-colton-haynes-1234798414/

Jones, D. (2022, August 12). Marcus Mumford says he “actually really begged” Winston Marshall not to leave mumford & sons. NME. https://www.nme.com/news/music/marcus-mumford-says-he-actually-really-begged-winston-marshall-not-to-leave-mumford-sons-3288188

Lane, B. (2023, August 1). Morgan Wallen has dominated the US charts this year, even after famously using a racial slur. Here is a complete timeline of his biggest controversies. Insider. https://www.insider.com/morgan-wallen-timeline-controversies-racial-slur-2023-3#february-2-2021-video-emerges-of-wallen-using-a-racial-slur-6

Moon, W. (2018). Fandom In Politics: Scale Development And Validation. (Master’s thesis). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/4879

Norris, R. (2020, June 1). Thomas Rhett and Lauren Akins share their support for black lives matter. Country Living. https://www.countryliving.com/life/a32731514/thomas-rhett-and-lauren-akins-black-lives-matter-movement/

Penumbra, AZSuburbs, & Lyssa. (2023, November 21 & 25) X. Twitter. https://twitter.com/search?q=country+music+hate&src=typed_query&f=top

Phy. (2023, November 26). X. Twitter. https://twitter.com/search?q=country+music+hate&src=typed_query&f=top

Primavera, M. (2023, August 22). 20+ memes for everyone who straight up hates country music. Pleated Jeans. https://pleated-jeans.com/2023/08/22/people-who-hate-country-music-memes/

Pyo, J. Y. (2023). Haters as Anti-Fans? Accruing Capital through Audiences Who Hate Journalists. Digital Journalism, ahead-of-print(ahead-of-print), 1–17. https://www-tandfonline-com.proxy.library.brocku.ca/doi/full/10.1080/21670811.2023.2191331

Wiggins, C. (2023, May 31). Country music star Zach Bryan calls out transphobia. Advocate.com. https://www.advocate.com/people/zach-bryan-calls-out-transphobia

Willman, Chris. (2005). Rednecks & bluenecks : the politics of country music. New Press.

Youngs, I. (2022, December 22). Rex orange county: Singer has sexual assault charges dropped before trial. BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/entertainment-arts-64063665