62 Quality over Quantity: K-Pop Fans and Physical Album Deterioration

Brynna Rafferty

Brynna L. Rafferty

Department of Communication, Pop Culture, and Film, Brock University

COMM 3P18: Audience Studies

Professor Derek Foster

December 4, 2023

Quantity over Quality: K-Pop Fans and Physical Album Deterioration

With the rise of digital communications, a third wave of fandom studies has emerged focusing on the normalcy of fan activity (Guo, 2017, p. 148). This third wave differs from its predecessors in that it observes fandom as part of everyday life. Fandom is now a form of activism, not resistance from the mainstream nor mere participation in attempts to integrate fan practices into other aspects of life. Activism in this third phase of fandom study is best defined by Fuschillo (2020) as, “[when] fans use all their consumption-related skills, practices, and competences with the support of net-worked communications to make a difference” (p. 356). This idea of making a difference in a fandom can be social, political, or financial. Essentially, the goal of fan-activism is using digital means to rally around a cause and change the market for the benefit of a fandom or fan-object.

Social media platforms, such as X (formerly Twitter), Facebook, Instagram, Discord, etc., are all essential mediums for fan-activism, hosting the majority of modern online fandoms. Anyone who regularly frequents these different platforms and observes users’ behaviours can vouch for the intensity of today’s active online fandoms. This intensity is evident because the Internet provides an ease of access to fandom that never existed before. Through the Internet, “faster and easier access has also facilitated an increase in the sharing of information about media content, often by so called multipliers” (Linden & Linden, 2017, p. 10). An increase in sharing of fandom information globally suggests a natural progression of fandom as normalcy. The more these multipliers share information by online means, the larger a fandom grows, and the larger a fandom grows, the more consumers exist in the digital fandom space. Following this progression, Linden & Linden (2020) suggest multipliers participate in shaping the landscape of online consumer markets (p. 10).

One fandom filled with multipliers and effective for further third wave fan research is Korean Pop (K-Pop), visible on almost every current social media platform, most notably X and TikTok. K-Pop fans are notorious for sharing clips of their favourite idols as well as buying and creating their own merchandise representing their favourite group(s). The reason for this intense degree of fandom can be summated to the relationship K-Pop companies form between idols and fans. Through exclusive K-Pop streaming platforms like the now-annulled V Live app, idols are able to display a constructed ‘authentic’ version of themselves to their massive audiences (King-O’Riain, 2020). By being involved in different media contents daily such as livestreams, variety shows, vlogs, etc., K-Pop group members show fans a side of themselves that most Western celebrities tend to hide. This display of a genuine self, one that can relate to the lives and experiences of an audience, causes fans to put a level of emotional investment into K-Pop idols/groups not seen in other fandoms. As King-O’Riain (2021) puts it, “often garnering upward of hundreds of thousands of viewers at a time, this has meant that K-pop idols must learn to create a sense of intimate connection while still addressing a mass crowd via V Live” (p. 2822). King-O’Riain explains here that because idols are trained to create an emotional connection with their digital audiences, it is only natural that international fans display an intense passion for K-Pop that they may not hold for other fandoms they are part of.

This passion for K-Pop has translated into global online communities where fans are able to discuss their favourite groups and become multipliers. Fans become multipliers by garnering attention for their respective groups through music videos, funny variety show clips, live performances, and even creating edits of their favourite idol. These K-Pop multipliers are taken advantage of through free labour by K-Pop companies to promote their groups, Guo (2017) noting, “media corporations are eager to employ, or perhaps exploit, online fan communities that are eager to discuss anything related to their favorite media topics…companies view fan discussions as a form of free advertising” (p. 155). This is not news to K-Pop fans, however, as many are self-aware of their power, evident through complaints on social media. This point is discussed further throughout the paper, focusing on the recent outrage K-Pop fans have displayed over the quality of physical albums they are buying—a major source of profit for these companies.

This paper argues through primary and secondary research of consumer behaviours in fandom that the collective voice of an audience matters for a musical act’s online presence and reflected album sales. Research on K-Pop fans as a consumer fandom is introduced prior to the study to give an overview of just how important these consumers are to the industry at large. Through social media posts on X of self-identified “stans” of K-Pop group Stray Kids, the scope of the research is limited to their opinions regarding an alleged decrease in quality of the group’s physical music albums. The goal of this research is to provide evidence concerning the self-aware nature of an audience consuming material merchandise.

Consumer Fandom and K-Pop

K-Pop can easily be categorised as an active consumer fandom because, as described by Linden and Linden (2020), an active audience is one that “is busy making meaning. This involves our senses… Anything we take in through the senses has to be processed, interpreted, fit into our expectations of what the world looks, sounds, and feels like” (p. 69). On social media, K-Pop fans are constantly “making meaning.” Through edits, self-made merch, and even fan theories surrounding groups with an established fictional storyline like BTS, fans have proven they are not passively listening to a group’s next album. They are consuming and creating new meanings regarding their favourite musical groups.

Part of what defines a consumer fandom is just that, being a consumer. Not only do K-Pop fans listen to music, but can be described as idealconsumers. Linden and Linden (2017) find:

The ideal consumers are active “co-producers”…with “followers” of their own. This places certain demands on the consumer—he or she needs to participate and co-create the product and experience, as well as market it actively and passionately. The new contract between the producer and the user stipulates the customers have to…spread the word and prolong—and amplify—the “text.” (p. 4).

This idea of K-Pop fans as “ideal consumers” sometimes comes in the form of their well-known intense political and social activism. Bruner (2020) highlights this activism by noting, “[K-Pop fans] have been known to deploy their influence over the years in the service of causes ranging from human rights campaigns to education programs, often in the names of the idols they support.” While touching on political fandom, this example still applies to Linden and Linden’s notion that as ideal consumers, K-Pop fans are passionate about causes in the names of their fan-object. Through this, they are able to reach communities outside of K-Pop which in turn only widens their audience, garnering the attention of like-minded people.

“Spreading the word” about music and important social causes is not the only way K-Pop fans act as “ideal consumers.” They are also active participants in buying large numbers of physical albums to elevate their status in their respective fandoms. So much so that “South Korea is one of the only music markets in the world where physical CD albums are on the rise” (Gloria 2021). This is partially because of the aforementioned passion fans possess for K-Pop that is not typically seen in Western media. Feeling like they “know” their favourite celebrities is part of the fun in the community, buying albums to prove just how much their fan-object has affected them. Passion, however, is not the only reason fans buy physical albums in K-Pop. Hedonic motivations as well as how these albums are strategically marketed play a major role in why K-Pop fans are such intense material consumers.

When studying the buying habits of K-Pop fans, Lestari and Tiarawati (2020) categorise consumer motivation into hedonic and utilitarian. Utilitarian motivation is based upon one’s physiological needs like food or clothing (p. 68). Hedonic motivation, on the other hand, is “motivation that arises because of psychological needs such as satisfaction, prestige, emotions and other subjective feelings” (p. 68). Given the nature of K-Pop, it is obvious consumers of the genre are buying physical albums for hedonic motivations. These psychological “needs” go beyond passion for music or idols, however. Album buying has created another subculture within the larger K-Pop digital community: photocard trading and its material relation to fandom status.

Collecting physical K-Pop albums is so much more than having pretty CDs to display on your shelf. In online communities, owning albums is about showing others those albums. In a study discussing brand loyalty and digital music fandoms, Obiegbu et al. (2019) find through interviews with fans of the band U2 that “fans provide evidence for their claims of obsession by drawing parallels with money spent in engaging their fandom, and stressing their collecting behaviour, and frequency of activity [online]” (p. 472). Much like older Western bands, K-Pop fans find validation in others approving of their collection. What sets K-Pop apart, however, is the inclusion of photocards in their albums.

Gloria (2021) describes photocards as, “special cards [which] typically have unreleased selfies or pictures of K-pop group members printed on them and are inserted into merchandise packages, the most common being music albums and video CDs…” (para. 5). Essentially, think of something like a baseball card, but with a funny selfie of a K-Pop idol rather than a professional baseball player. These cards are placed into albums at random, so a fan never knows what member they are going to receive. Due to financial reasons, rather than buying multiple albums until obtaining a desired member, K-Pop fans take to social media and trade and sell these photocards amongst each other. This creates a subculture within the overall K-Pop fandom and keeps physical album sales on the rise. Fans place these photocards in special binders or display them in an “aesthetic” way to post on social media and prove their status in their respective sub-fandom. An example of this display of status is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1

Aesthetic Display of BTS’s Jimin Photocards

Note. Image comes from user fairyprincejm on Instagram.

Given the intensity of K-Pop fan culture as proven by aforementioned online practices, there is a term that would be more fitting for the community than just a fan: a stan. For the purpose of this research, a “stan” is defined as “an overzealous or obsessive fan of a particular celebrity” (Oxford Languages, n.d.). Recently integrated into the English dictionary due to its frequent use, the slang originates from rapper Eminem’s allegory of a song, “Stan,” depicting a man being pushed to insanity when his idol does not respond to his mail (Madden 2019). Given its origin and dictionary definition, it is easy to give “stan” a negative connotation. Fans of K-Pop, however, take pride in being called the term. Reddit user mycatlikesmaths writes, “…People will expect that you not only know the group’s entire discography and keep up with their musical releases, but also keep up with their other schedules, vlogs, follow them on some social media, perhaps have an active fan account where you post about them a lot compared to other groups, etc.” Here is an example of the word stan being used as what most know as a traditional fan rather than an obsessed stalker, keeping up with a group’s activities. Since Eminem’s release of the song, it is evident the definition of the slang term has been diluted to an everyday term describing an online fan. For the purpose of this research, K-Pop fans interacting online will be interchangeably called stans given the frequency and relevancy of the term.

Stray Kids and Physical Albums

Stray Kids is a male idol group who made their debut in 2018 under J.Y.P Entertainment (JYPE). Since their debut, they have made waves not only in South Korea, but in the West as well, most notably the United States. With their bombastic, almost “in-your-face” sound, they have been able to garner attention that may soon parallel the success of BTS. According to Caulfield (2023), Stray Kids’s most recent album ROCK-STAR debuted at “No. 1 on the Billboard 200 albums chart (dated Nov. 25), scoring the Korean pop ensemble its fourth chart topper” (para. 1). So, not only did the group score a No. 1 on a U.S. music chart, but this is the group’s fourth time doing so. To further emphasise the group’s recent success, Zellner (2023) notes “Stray Kids are officially Billboard Hot 100-charting artists, as the group scores its first entry on the Nov. 25-dated list with ‘LALALALA’” (para. 1). Both their album and title track from said album have charted on the top of two different charts from Billboard, suggesting the size of their fanbase and intensity of their consumer practices both traditionally and online.

Given the group’s success, Stray Kids have acquired a passionate community online through their fanbase, Stay. Stay have been loud and proud on different social media platforms, celebrating every win in both the East and West no matter the hate received from other competing K-Pop fanbases, including BTS’s ARMY. No matter the support from Stay, however, Stray Kids’s recent albums do not come without criticism. It is important to note this criticism is not aimed at the group, but rather those in charge of selling their albums, their company: JYPE. Provided there are a number of issues Stay have with JYPE, the focused issue for this research is the fanbase’s very vocal opposition regarding how Stray Kids’s latest albums have been packaged.

While similar issues have been found throughout K-Pop stan circles online, including BTS’s last few albums, Stray Kids and Stay are the focus of this research because of the recency of the group’s latest album and its popularity online. To add, BTS has been the centre of K-Pop stan culture for nearly a decade given their unparalleled success. Researching a newer group offers a new perspective regarding the state of the K-Pop community as a whole rather than one faction of the fandom.

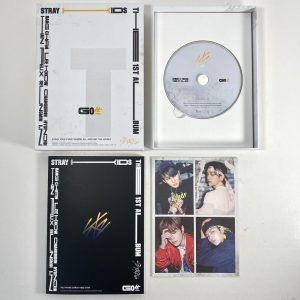

When discussing the current iteration of Stray Kids’s physical album quality, it is important to discuss what a usual K-Pop album looks like. They are much different from the physical albums of Western artists. Rather than a CD placed in a square plastic container, also known as a jewel case, K-Pop albums are packaged “in various formats, including slip cases, box sets, and custom packages…often housing additional merchandise, such as photo books or DVDs” (Kinsher, 2023, para. 10). Figure 2 shows an example of an earlier Stray Kids album, GO LIVE, for reference.

Figure 2

Go Live Album

Note. The image includes a large white box which houses a CD, black photo book, and a 4-cut photo of the members—photocards are also included, just not present in the image.

It is this large DVD-like display that adds to the collectability of these albums. Given this orientation with inclusions like photocards, posters, and a photo book of the group, K-Pop albums are not cheap, usually fetching a price of $25-$35 USD. With average prices like these, Stay have become restless on social media over the quality of Stray Kids’s recent physical albums. ROCK-STAR, for instance, provides an unstable, almost flimsy cover with only one photocard included compared to Stray Kids’s usual three to four photocards per album. User jedeviennefou on X proves this with a picture including the group’s latest four albums (Figure 3). From the left is ODDINARY, a Stray Kids album from March 2023 and the oldest album in the figure. This album boasts a red box made of a hard cardboard material for an impactful display that will last a collector a long time. From then on, the following albums, MAXIDENT, 5-STAR, and ROCK-STAR are pictured. The figure displays a sort of deterioration in quality, the albums getting thinner as well as weaker in material as time goes on, ROCK-STAR debuting in November of 2023. Like jedeviennefou, most of Stay’s outcries come from X given that the K-Pop fandom “has been a major contributor to [its] growing popularity as a social media platform” (Malik & Haidar, 2019, p. 734). Stay is now a major part of the larger K-Pop community on X, and because of their overwhelming presence as multipliers on the app, their voice matters.

Figure 3

Stray Kids Albums over Time

Note. Earliest to latest albums are displayed from left to right.

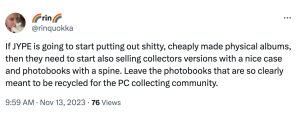

If X is the most frequented platform for K-Pop stans, it is also where they are most influenced. This means stans are listening to other stans—if a Stay creates a post giving a negative opinion on the state of the Stray Kids album they paid full price for, others will listen and likely be hesitant to continue buying. For instance, user sunnyhyunnie on X posts “ …if their next physical album is the same design/quality I’m just not gonna buy it…they need to know it’s unacceptable.” ‘They’ here refers to JYPE, or the company in charge of Stray Kids, which is usually who stans point fingers to regarding issues such as album quality. Another user, rinquokka, even offers a new angle to market, using harsh language to enhance the anger they and many other Stay feel regarding the digression of albums (Figure 4).

Figure 4

Statement from User rinquokka on X

Along with harsh language comes gentler words, user Ashaskz posting, “I love [Stray Kids] physical albums and it’s the reason I keep buying but the quality is so sad…” This range of emotions displayed through a variety of users all have something in common: there is no positive connotation associated with Stray Kids’s latest physical album release. There is a clear surplus of backlash JYPE has received from Stay within the last month at the time this research is being done, the posts mentioned above proving so, being only a miniscule percentage. With this current discourse throughout X and other platforms, JYPE may see a decline in physical unit sales if the company continues with this level of quality.

Discussion

Stay’s opinions reflect that the higher the sales, the more JYPE and other media companies believe they can exploit consumers by mass producing albums on a scale that leads to a lack of quality. This fact is further proven through previous research provided by Shihab and Putri (2019) about negative online reviews and popular products. In their study they conclude, “A high proportion of negative online reviews of a popular product was shown to significantly depress consumers’ attitude when compared to a low proportion of negative online reviews” (p. 174). This outcome coincides with Stay and the many negative reviews found on X of Stray Kids’s recent physical album. Because albums are the most popular merchandising product from the company, it is important that stans are heard where they frequent the most, online global communities on platforms such as X. If not, these “depressed attitudes” of Stay seen in consumers of popular products could translate to a decline in overall sales.

Conclusion

Companies like JYPE bank on the parasocial relationships stans form with their favourite idols to accelerate music video views, online discourse, and physical album sales. It has been made clear through sub-fandoms like Stay, however, that it is these same stans that hold the power to change the growth of K-Pop as multipliers. An increase in sales has led to a decrease in a once major appeal to the K-Pop community. This exploitation of passionate fans online spreading the word of their favourite groups has not gone unnoticed, proven throughout the essay that stans such as Stay are self-aware of their buying habits. They understand that such a drastic decrease in album quality is not worth interfering with their utilitarian purchases necessary to live comfortably.

K-Pop has proven in recent years to be a large market, connecting people globally through digital means. It is just a small example, however, of overall consumer fandom practices. If K-Pop stans can take control of the narrative regarding how products of their fan-object(s) are marketed, the same can be said for a plethora of other consumer fandoms, proving the research’s importance.

References

[mycatlikesmaths]. (2022, June 22). These days “stan” is just used as a subcategory. Reddit. https://www.reddit.com/r/kpophelp/comments/vhpv9n/comment/idb7y7v/?utm_source=share&utm_medium=web3x&utm_name=web3xcss&utm_term=1&utm_content=share_button

이리노야. [@Ashaskz]. (2023, November 13). i love skz physical albums and it’s the reason i keep buying but the quality is so sad…[Post]. X. https://x.com/Ashaskz/status/1724032622840738097?s=20

Bruner, R. (2020). How K-Pop Fans Actually Work as a Force for Political Activism in 2020. TIME. Retrieved December 12, 2023, from https://time.com/5866955/k-pop-political/.

Caulfield, K. (2023). Stray Kids Score Fourth No. 1 on Billboard 200 With ‘ROCK-STAR’. Billboard. Retrieved December 4, 2023, from https://www.billboard.com/music/chart-beat/stray-kids-rock-star-number-1-billboard-200-1235494895/

Fuschillo, G. (2020). Fans, fandoms, or fanaticism? Journal of Consumer Culture, 20(3), 347–365. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469540518773822

Gloria, G. (2022). Why K-Pop Fans Are Buying, Trading, and Selling Photos of Their Idols. Vice. Retrieved December 4, 2023, from https://www.vice.com/en/article/qjbenx/what-kpop-photocard-why-collect-price-expensive

Guo, S. (2018). Charging Fandom in the Digital Age: The Rise of Social Media. In C. Lu Wang (Ed.), Exploring the Rise of Fandom in Contemporary Consumer Culture (pp. 147-162). IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-5225-3220-0.ch008

King-O’Riain, R. C. (2021). “They were having so much fun, so genuinely . . .”: K-pop fan online affect and corroborated authenticity. New Media & Society, 23(9), 2820–2838. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444820941194

Kinsher, P. (2023). What You can Learn from K-Pop Album Packaging. Disk Makers. Retrieved December 12, 2023. https://blog.discmakers.com/2023/08/kpop-album-packaging-to-boost-cd-sales/

Lestari, D. A., & Tiarawati, M. (2020). The Effect of Hedonic Motivation and Consumer Attitudes Towards Purchase Decision on K-Pop CD Albums (Study on KPOPSURABAYA Community). Spirit of Society Journal: International Journal of Society Development and Engagement (Online), 3(2), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.29138/scj.v3i2.1084

Linden, H., & Linden, S. (2017). Introduction. In Fans and Fan Cultures (pp. 1–7). Palgrave Macmillan UK. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-50129-5_2

Linden, H., & Linden, S. (2017). Fans, Followers and Brand Advocates. In Fans and Fan Cultures (pp. 9–35). Palgrave Macmillan UK. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-50129-5_2

Madden, S, (2019). The 2010s: Social Media And The Birth Of Stan Culture. NPR. Retrieved December 12, 2023. https://www.npr.org/2019/10/07/767903704/the-2010s-social-media-and-the-birth-of-stan-culture

Malik, Z., & Haidar, S. (2023). Online community development through social interaction – K-Pop stan twitter as a community of practice. Interactive Learning Environments, 31(2), 733–751. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2020.1805773

Mel. [@fairyprincejm]. Happy Jimin Day!! [Photograph]. Instagram. https://www.instagram.com/p/CyTZeG9vBHp/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link&igshid=N2ViNmM2MDRjNw==

Obiegbu, C. J., Larsen, G., Ellis, N., & O’Reilly, D. (2019). Co-constructing loyalty in an era of digital music fandom An experiential-discursive perspective. European Journal of Marketing, 53(3), 463–482. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-10-2017-0754

Rin. [@rinquokka]. (2023, November 13). If JYPE is going to start putting out shitty, cheaply made physical albums, then they need to start also selling collectors versions with a nice case and photobooks with a spine. [Post]. X. https://x.com/rinquokka/status/1724079522343956908?s=20

Sate. [@jedeviennefou]. (2023, November 12). [Image attached]. [Post]. X. https://twitter.com/jedeviennefou/media

Sunny. [@sunnyhyunnie]. (2023, November 13). Fr though if their next physical album is the same design/quality i’m just not gonna buy it. [Post]. X. https://twitter.com/sunnyhyunnie

Shihab, M. R., & Putri, A. P. (2019). Negative online reviews of popular products: understanding the effects of review proportion and quality on consumers’ attitude and intention to buy. Electronic Commerce Research, 19(1), 159–187. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10660-018-9294-y

Zellner, X. (2023). Hot 100 First-Timers: Stray Kids Debut With ‘LALALALA’ From New No. 1 Album ‘ROCK-STAR’. Billboard. Retrieved December 4, 2023, from https://www.billboard.com/music/chart-beat/stray-kids-hot-100-debut-lalalala-1235500331/