1 Introduction to Child Development

Chapter Objectives

After this chapter, you should be able to:

- Describe the principles that underlie development.

- Differentiate periods of human development.

- Understand issues in development.

- Distinguish the different methods of research.

- Explain what a theory is and compare and contrast different theories of child development.

Introduction

“Early child development sets the foundation for lifelong learning, behaviour, and health” (Mustard, 2006).

Welcome to Child Growth and Development. This text is a presentation of how and why children grow, develop, and learn from conception to adolescence. Registered early childhood educators (RECEs) draw from their professional knowledge of child development, learning theories, and pedagogical and curricular approaches to plan, implement, document and assess child-centered inquiry and play-based learning experiences for children (College of Early Childhood Educators, 2017, p. 10). Understanding the patterns of development help early childhood educators build caring and responsive relationships (College of Early Childhood Educators, 2017) with the children in their care as well as design safe and accessible environments which support children’s play and learning (College of Early Childhood Educators, 2017), both of which contribute to a sense of belonging and overall well-being (Ontario Ministry of Education, 2014b).

The content in this text is being shared with pre-service early childhood educators with an Ontario context, referring to foundational documents that support the early learning and care profession, including, but not exclusive of: The Code of Ethics and Standards of Practice for Early Childhood Educators in Ontario, How Does Learning Happen? and Excerpts from ELECT.

Principles of Development

There are several underlying principles of development to keep in mind:

- Development is lifelong and change is apparent across the lifespan (although this text ends with adolescence). Early experiences affect later development.

- Development is multidirectional. We show gains in some areas of development while showing a loss in other areas.

- Development is multidimensional. We change across three general domains/dimensions: physical, cognitive, and social-emotional.

In Ontario, the Continuum of Development can be found in the Excerpts to ELECT. It outlines the sequence of steps across the five domains of development (social, emotional, communication/language/literacy, cognition, physical) that are typical for the majority of children. It is not an assessment tool, rather it was designed to support RECEs as they observe and document children’s emerging skills (Ontario Ministry of Education, 2014). It should be noted that all five domains are interrelated and no one domain is more important than another (Ontario Ministry of Education, 2014a).

Research in child development tends to fall into one of the following four themes:

- Early Development is related to later development but not perfectly. Can you think of examples?

- Development is always jointly influenced by heredity and environment (nature/nurture).

- Children help to determine their own development. Can you think of examples?

- Development in different domains is connected.

The physical domain includes changes in height and weight, changes in gross and fine motor skills, sensory capabilities, the nervous system, as well as the propensity for disease and illness.

The cognitive domain encompasses the changes in intelligence, wisdom, perception, problem-solving, memory, and language.

The social and emotional domain (also referred to as psychosocial) focuses on changes in emotion, self-perception, and interpersonal relationships with families, peers, and friends.

All three domains influence each other. It is also important to note that a change in one domain may cascade and prompt changes in the other domains.

Development is characterized by plasticity, which is our ability to change, and that many of our characteristics are malleable. Early experiences are important, but children are remarkably resilient (able to overcome adversity).

Development is multicontextual (Lally & Valentine-French, 2019). We are influenced by both nature (genetics) and nurture (the environment) – when and where we live and our actions, beliefs, and values are a response to circumstances surrounding us. The key here is to understand that behaviours, motivations, emotions, and choices are all part of a bigger picture (Lumen Learning, n.d.).

Now let’s look at a framework for examining development.

Periods of development

Consider what periods of development you think a course on Child Development would address. How many stages are on your list? Perhaps you have three: infancy, childhood, and teenagers.

Developmentalists (those that study development) break this part of the life span into these five stages as follows:

- Prenatal Development (conception through birth)

- Infancy and Toddlerhood (birth through 30 months)

- Early Childhood (2.5 to 5 years)

- Middle Childhood (6 to 12 years)

- Adolescence (13 years to adulthood)

The scope of practice of a registered early childhood educator in Ontario is to work with children twelve years old and younger (College of Early Childhood Educators, 2017), thus the first four stages in this list will be explored in this book. So, while both an 8-month-old and an 8-year-old are considered children, they have very different physical, social, emotional, language, and cognitive skills and abilities.

prenatal development

Conception occurs and development begins. All of the major structures of the body are forming and the health of the mother is of primary concern. Understanding nutrition, teratogens (or environmental factors that can lead to birth defects), and labor and delivery are primary concerns.

infancy and toddlerhood

The first two years of life are ones of dramatic growth and change. A newborn, with a keen sense of hearing but very poor vision is transformed into a walking, talking toddler within a relatively short period of time. Caregivers are also transformed from someone who manages the feeding and sleep schedules to a constantly moving guide and safety inspector for a mobile, energetic child.

Early childhood

Early childhood is also referred to as the preschool years and consists of the years which follow toddlerhood and precede formal schooling (grade 1). As a three to five-year-old, the child is busy learning a language, is gaining a sense of self and greater independence and is beginning to learn the workings of the physical world. This knowledge does not come quickly, however, and preschoolers may initially have interesting conceptions of size, time, space, and distance such as fearing that they may go down the drain if they sit at the front of the bathtub or by demonstrating how long something will take by holding out their two index fingers several inches apart. A toddler’s fierce determination to do something may give way to a four-year-old’s sense of guilt for action that brings the disapproval of others.

middle childhood

The ages of six through twelve comprise middle childhood and much of what children experience at this age is connected to their involvement in the early grades of school. Now the world becomes one of learning and testing new academic skills and of assessing one’s abilities and accomplishments by making comparisons between self and others. Schools compare students and make these comparisons public through team sports, test scores, and other forms of recognition. Growth rates slow down and children are able to refine their motor skills at this point in life. Children begin to learn about social relationships beyond the family through interaction with friends and fellow students.

adolescence

Adolescence is a period of dramatic physical change marked by an overall physical growth spurt and sexual maturation, known as puberty. It is also a time of cognitive change as the adolescent begins to think of new possibilities and to consider abstract concepts such as love, fear, and freedom. Ironically, adolescents have a sense of invincibility that puts them at greater risk of dying from accidents or contracting sexually transmitted infections that can have lifelong consequences (Lumen Learning, 2019).

Issues in Development

There are some aspects of development that have been hotly debated. Let’s explore these in a bit more detail.

Nature and Nurture

Why are people the way they are? Are features such as height, weight, personality, being diabetic, etc. the result of heredity or environmental factors-or both? For decades, scholars have carried on the “nature/nurture” debate. For any particular feature, those on the side of Nature would argue that heredity plays the most important role in bringing about that feature. Those on the side of Nurture would argue that one’s environment is most significant in shaping the way we are. This debate continues in all aspects of human development, and most scholars agree that there is a constant interplay between the two forces. It is difficult to isolate the root of any single behaviour as a result solely of nature or nurture. This said, research does consistently point to the fact that healthy child development depends on the relationships children have with parents and other important people in their lives (Bisnaire, Clinton & Ferguson, 2014).

Continuity versus Discontinuity

Is human development best characterized as a slow, gradual process, or is it best viewed as one of more abrupt change? The answer to that question often depends on which developmental theorist you ask and what topic is being studied. The theories of Freud, Erikson, Piaget, and Kohlberg are called stage theories. Stage theories or discontinuous development assume that developmental change often occurs in distinct stages that are qualitatively different from each other, and in a set, universal sequence. At each stage of development, children and adults have different qualities and characteristics. Thus, stage theorists assume development is more discontinuous. Others, such as the behaviourists, Vygotsky, and information processing theorists, assume development is a more slow and gradual process known as continuous development. For instance, they would see the adult as not possessing new skills, but more advanced skills that were already present in some form in the child. Brain development and environmental experiences contribute to the acquisition of more developed skills.

Active Vs Passive

How much do you play a role in your own developmental path? Are you at the whim of your genetic inheritance or the environment that surrounds you? Some theorists see humans as playing a much more active role in their own development. Piaget, for instance, believed that children actively explore their world and construct new ways of thinking to explain the things they experience. In contrast, many behaviourists view humans as being more passive in the developmental process (Lally & Valentine-French, 2019).

How do we know so much about how we grow, develop, and learn? Let’s look at how that data is gathered through research.

Research Methods

An important part of learning any science is having a basic knowledge of the techniques used in gathering information. The hallmark of scientific investigation is that of following a set of procedures designed to keep questioning or skepticism alive while describing, explaining, or testing any phenomenon. Some people are hesitant to trust academicians or researchers because they may seem to change their narratives. That, however, is exactly what science is all about; it involves continuously renewing our understanding of the subjects in question and an ongoing investigation of how and why events occur. Science is a vehicle for going on a never-ending journey. In the area of development, we have seen changes in recommendations for nutrition, in explanations of psychological states as people age, and in parenting advice. So think of learning about human development as a lifelong endeavour.

Take a moment to write down two things that you know about childhood. Now, how do you know? Chances are you know these things based on your own history (experiential reality) or based on what others have told you or cultural ideas (agreement reality) (Seccombe and Warner, 2004, as cited in Paris, Ricardo, Raymond, & Johnson, 2021). There are several problems with personal inquiry.

Read the following sentence aloud:

Paris in the the spring

…Are you sure that is what it said?

Read it again:

Paris in the the spring

If you read it differently the second time (adding the second “the”) you just experienced one of the problems with personal inquiry; that is, the tendency to see what we believe. Our assumptions very often guide our perceptions, consequently, when we believe something, we tend to see it even if it is not there. This problem may just be a result of cognitive ‘blinders’ or it may be part of a more conscious attempt to support our own views. Confirmation bias is the tendency to look for evidence that we are right and in so doing, we ignore contradictory evidence. Karl Popper was an Austrian-British philosopher, academic and social commentator. One of the 20th century’s most influential philosophers of science, Popper is known for his rejection of the classical inductivist views on the scientific method in favour of empirical falsification. He suggests that the distinction between that which is scientific and that which is unscientific is that science is falsifiable; scientific inquiry involves attempts to reject or refute a theory or set of assumptions (Thornton, 2005, as cited in Paris, Ricardo, Raymond, & Johnson, 2021). Theory that cannot be falsified is not scientific. And much of what we do in personal inquiry involves drawing conclusions based on what we have personally experienced or validating our own experience by discussing what we think is true with others who share the same views. Science offers a more systematic way to make comparisons guard against bias.

Scientific Methods

One method of scientific investigation involves the following steps:

- Determining a research question

- Reviewing previous studies addressing the topic in question (known as a literature review)

- Determining a method of gathering information

- Conducting the study

- Interpreting results

- Drawing conclusions; stating limitations of the study and suggestions for future research

- Making your findings available to others (both to share information and to have your work scrutinized by others)

Your findings can then be used by others as they explore the area of interest and through this process, a literature or knowledge base is established. This model of scientific investigation presents research as a linear process guided by a specific research question. And it typically involves quantifying or using statistics to understand and report what has been studied. Many academic journals publish reports on studies conducted in this manner.

Another model of research referred to as qualitative research may involve steps such as these:

- Begin with a broad area of interest

- Gain entrance into a group to be researched

- Gather field notes about the setting, the people, the structure, the activities, or other areas of interest

- Ask open-ended, broad “grand tour” types of questions when interviewing subjects

- Modify research questions as the study continues

- Note patterns or consistencies

- Explore new areas deemed important by the people being observed

- Report findings

In this type of research, theoretical ideas are “grounded” in the experiences of the participants. The researcher is the student and the people in the setting are the teachers as they inform the researcher of their world (Glazer & Strauss, 1967, as cited in Paris, Ricardo, Raymond, & Johnson, 2021). Researchers are to be aware of their own biases and assumptions, acknowledge them, and bracket them in efforts to keep them from limiting accuracy in reporting. Sometimes qualitative studies are used initially to explore a topic and more quantitative studies are used to test or explain what was first described.

Let’s look more closely at some techniques, or research methods used to describe, explain, or evaluate. Each of these designs has strengths and weaknesses and is sometimes used in combination with other designs within a single study.

Observational Studies

Observational studies involve watching and recording the actions of participants. This may take place in the natural setting, such as observing children at play at a park, or behind a one-way glass while children are at play in a laboratory playroom. The researcher may follow a checklist and record the frequency and duration of events (perhaps how many conflicts occur among 2-year-olds) or may observe and record as much as possible about an event (such as observing children in a classroom and capturing the details about the room design and what the children and teachers are doing and saying). In general, observational studies have the strength of allowing the researcher to see how people behave rather than relying on self-report. What people do and what they say they do are often very different. A major weakness of observational studies is that they do not allow the researcher to explain causal relationships. Yet, observational studies are useful and widely used when studying children. Children tend to change their behaviour when they know they are being watched (known as the Hawthorne effect) and may not survey well.

Experiments

Case Studies

Case studies involve exploring a single case or situation in great detail. Information may be gathered with the use of observation, interviews, testing, or other methods to uncover as much as possible about a person or situation. Case studies are helpful when investigating unusual situations such as brain trauma or children reared in isolation. And they are often used by clinicians who conduct case studies as part of their normal practice when gathering information about a client or patient coming in for treatment. Case studies can be used to explore areas about which little is known and can provide rich detail about situations or conditions. However, the findings from case studies cannot be generalized or applied to larger populations; this is because cases are not randomly selected and no control group is used for comparison.

Surveys

Surveys are familiar to most people because they are so widely used. Surveys enhance accessibility to subjects because they can be conducted in person, over the phone, through the mail, or online. A survey involves asking a standard set of questions to a group of subjects. In a highly structured survey, subjects are forced to choose from a response set such as “strongly disagree, disagree, undecided, agree, strongly agree”; or “0, 1-5, 6-10, etc.” This is known as the Likert Scale. Surveys are commonly used by sociologists, marketing researchers, political scientists, therapists, and others to gather information on many independent and dependent variables in a relatively short period of time. Surveys typically yield surface information on a wide variety of factors, but may not allow for an in-depth understanding of human behaviour.

Of course, surveys can be designed in a number of ways. They may include forced-choice questions and semi-structured questions in which the researcher allows the respondent to describe or give details about certain events. One of the most difficult aspects of designing a good survey is wording questions in an unbiased way and asking the right questions so that respondents can give a clear response rather than choosing “undecided” each time. Knowing that 30% of respondents are undecided is of little use! So a lot of time and effort should be placed on the construction of survey items. One of the benefits of having forced-choice items is that each response is coded so that the results can be quickly entered and analyzed using statistical software. The analysis takes much longer when respondents give lengthy responses that must be analyzed in a different way. Surveys are useful in examining stated values, attitudes, opinions, and reporting on practices. However, they are based on self-report or what people say they do rather than on observation and this can limit accuracy.

Developmental Designs

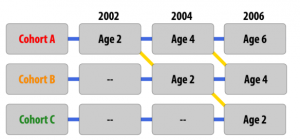

Developmental designs are techniques used in developmental research (and other areas as well). These techniques try to examine how age, cohort, gender, and social class impact development.

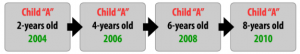

Longitudinal Research

Longitudinal research involves beginning with a group of people who may be of the same age and background, and measuring them repeatedly over a long period of time. One of the benefits of this type of research is that people can be followed through time and be compared with them when they were younger.

A problem with this type of research is that it is very expensive and subjects may drop out over time.

In Canada, the National Longitudinal Survey of Children and Youth which began in 1994 is an example of a longitudinal study that provided data on children’s development. Surveys were conducted every 2 years with the last survey conducted in 2008-2009. The sample size was roughly 26,000 children aged 0-23 years.

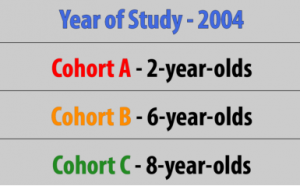

Cross-Sectional Research

Cross-sectional research involves beginning with a sample that represents a cross-section of the population. Respondents who vary in age, gender, ethnicity, and social class might be asked to complete a survey about television program preferences or attitudes toward the use of the internet. The attitudes of males and females could then be compared, as could attitudes based on age. In cross-sectional research, respondents are measured only once.

This method is much less expensive than longitudinal research but does not allow the researcher to distinguish between the impact of age and the cohort effect. Different attitudes about the use of technology, for example, might not be altered by a person’s biological age as much as their life experiences as members of a cohort.

Sequential Research

Sequential research involves combining aspects of the previous two techniques; beginning with a cross-sectional sample and measuring them through time.

This is the perfect model for looking at age, gender, social class, and ethnicity. But the drawbacks of high costs and attrition are here as well (Lumen Learning, n.d.).

| Type of Research Design | Advantages | Disadvantages |

| Longitudinal |

|

|

| Cross-sectional |

|

|

| Sequential |

|

|

Table 1.1: Advantages and disadvantages of different research designs, (Lukowski & Milojevich, 2021).

Qualitative Research in Early Childhood

Qualitative research involves describing and explaining an individual or group experience, a phenomenon or a situation. Such research is conducted with a focus on discovery and therefore open-ended. Information (data) collected and analyzed are in the form of narratives and images obtained from in-depth interviews, observations, documents, and physical artifacts. The following are some research methods used in qualitative research.

|

Method |

Purpose |

|

Biography |

To study lives of individuals. Collect stories and report individual experiences. E.g.. Early educator’s living and working experience in northern rural communities in British Columbia. |

|

Grounded theory |

To generate a theory that explains a phenomenon. Study processes, activities and events that occur. E.g. Coping strategies of children and families living with aplastic anemia. |

|

Ethnography |

To study culture of a particular group. Describe and interpret shared patterns of behaviour, beliefs and language. E.g. Children, families and educators in Forest Schools. |

Table 1.2: Qualitative research methods, (Lukowski & Milojevich, 2021)

Canada’s Contribution to Child Development Research

Canada has a long history of contributing to child development research.

In 1892, James Mark Baldwin was appointed the first social scientist at the University of Toronto where he set up Canada’s first psychological research laboratory. Baldwin proposed a social psychological perspective in studying child development and believed that development occurs in stages. He explained that development of physical movement proceeds from simple to complex and eventually leads to more sophisticated mental processes. Jean Piaget (1896 – 1980) later advanced this idea further.

Dr. Jean Clinton of McMaster University (Hamilton, Ontario) is an internationally renowned advocate for children’s issues. Her research focus is in brain development and the role social relationships play in development.

Dr. Fraser Mustard (1927-2011) created the “Canadian Institute for Advanced Research”. Of particular interest to Dr. Mustard was the role of communities in early childhood. In 1999, along with Dr. Margaret McCain (1934- ), he prepared the influential report “The Early Years Study – Reversing the Real Brain Drain” for the Ontario government. The report emphasized promoting early child development centres for young children and parents by: boosting spending on early childhood education to the same levels as in K to 12, making programs available to all income levels, and encouraging local parent groups and businesses to set up these programs instead of the government, when possible. In 2007, Dr. Mustard, Dr. McCain and Dr. Stuart Shanker wrote a follow-up report critical of Ontario’s progress and calling for national early childhood development programs.

Dr. Stuart Shanker (1952- ) is Canada’s leading expert in the psychosocial theory of self-regulation. Richard Tremblay (1944- ) holds the Canadian Research Chair in Child Development. His research focusses on the development of aggressive behaviour in children and whether early intervention programs can reduce chances of children turning to crime as adults. Dr. Mariana Brussoni of the University of British Columbia is currently active researching the developmental importance of risky play in childhood. Her focus is child injury prevention as well as the influence of culture on parenting in relationship to risky play and safety.

In 1925, Professor Edward Alexander Bott established the St. George’s School for Child Study at the University of Toronto, which would eventually come to be known as The Institute for Child Study. It has been and continues to be, highly influential in developing Ontario’s early childcare and education system.

Statistics Canada, in partnership with Human Resources Development Canada, undertook a major Canadian research initiative in 1994 titled “National Longitudinal Survey of Children and Youth (NLSCY)”. Researchers tracked multiple variables affecting children’s emotional, social and behavioural development over a period of time, using both longitudinal and cross-sectional sampling. Families from all 10 provinces and territories were included with the exception of families living on First Nations reserves, in extremely remote areas of Canada and full-time members the Canadian Armed Forces. These exclusions should be kept in mind when extrapolating the data.

This is just a small selection of Canadian researchers who have contributed, and continue to contribute, to our knowledge of how best to support the development of young children.

Consent and Ethics in Research

Research should, as much as possible, be based on participants’ freely volunteered informed consent. For minors, this also requires consent from their legal guardians. This implies a responsibility to explain fully and meaningfully to both the child and their guardians what the research is about and how it will be disseminated. Participants and their legal guardians should be aware of the research purpose and procedures, their right to refuse to participate; the extent to which confidentiality will be maintained; the potential uses to which the data might be put; the foreseeable risks and expected benefits; and that participants have the right to discontinue at any time.

But consent alone does not absolve the responsibility of researchers to anticipate and guard against potential harmful consequences for participants (Lumen Learning, n.d.). It is critical that researchers protect all rights of the participants including

Confidentiality.

The Canadian Psychological Association (2017) has published the Canadian Code of Ethics for Psychologists, which sets out four ethical principles Canadian psychologists must consider when conducting research: In order of priority, the four principles are:

- Principle I: Respect for the Dignity of Persons and Peoples

- Principle II: Responsible Caring

- Principle III: Integrity in Relationships

- Principle IV: Responsibility to Society

While all four principles should be taken into account, there may be times when there is a conflict between the principles. For example; what is best for society might not respect the dignity of persons and people. In this situation, more weight should be given to Principle 1 than Principle 4 in order to make an ethical decision.

Child development is a fascinating field of study – but care must be taken to ensure that researchers use appropriate methods to examine infant and child behaviour, use the correct experimental design to answer their questions, and be aware of the special challenges that are part-and-parcel of developmental research. Hopefully, this information helped you develop an understanding of these various issues and to be ready to think more critically about research questions that interest you. There are so many interesting questions that remain to be examined by future generations of developmental scientists – maybe you will make one of the next big discoveries! Another really important framework to use when trying to understand children’s development are theories of development.

Let’s explore what theories are and introduce you to some major theories in child development.

Developmental Theories

The College of Early Childhood Educators (2017), clearly articulates in a number of places in the Code of Ethics & Standards of Practice for Early Childhood Educators in Ontario, the expectation that RECEs are as knowledgeable about research and theories related to children’s development. Let’s explore what is meant by a child development theory and why they are important to practice.

What is a theory?

In our attempts to make sense of the world and our human experience, it is in our nature to ask questions and develop theories, both formal and informal. This begins at an early age and as we move through this text, we will explore examples of children developing and testing their theories.

While it is true that students sometimes feel intimidated by theory; even the phrase, “Now we are going to look at some theories…” is met with blank stares and other indications that the audience is now lost. But theories are valuable tools for understanding human behaviour and development. Indeed, they are proposed explanations for the “how” and “whys” of development. Have you ever wondered, “Why is my 3 year old so inquisitive?” or “Why are some fifth graders rejected by their classmates?” A theory is an organized way to make sense of information. Theories can help to make predictions and explain these and other occurrences. Theories can be further tested through research. Developmental theories offer explanations about how we develop, why we change over time, and the kinds of influences that impact development.

Further, a theory guides how information is collected, how it is interpreted, and how it is applied to real-life situations. It provides the researcher with a blueprint or model to be used to help piece together various studies. Think of theories as frameworks or guidelines much like directions that come with an appliance or other object that requires assembly. The instructions can help one piece together smaller parts more easily than if trial and error are used.

Theories can be developed using induction in which a number of single cases are observed and after patterns or similarities are noted, the theorist develops ideas based on these examples. Established theories are then tested through research; however, not all theories are equally suited to scientific investigation. Some theories are difficult to test but are still useful in stimulating debate or providing concepts that have practical application. Keep in mind that theories are not facts; they are guidelines for investigation and practice, and they gain credibility through research that fails to disprove them (Lumen Learning, n.d.).

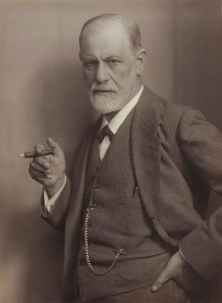

Before we examine some foundational child development theories, let’s take a preliminary look at the theorists who have contributed to our current understanding of child development. Take a moment to scan the images of the theorists included in the next few pages. Find some words to describe what you notice. Can you identify groups who are not represented in this group of theorists? If your answer included women, people of colour, visible minorities and/or Indigenous people as examples you are correct!

Academics and researchers have, and do, develop theories and frameworks for thinking critically about human knowledge and systems. Critical theory is an example of a postmodern theory the aim of which is to unmask the ideology that falsely justifies some form of economic or social oppression and to see it for what it is…ideology! This can set in motion the task of ending the oppression.

Today many nations are actively addressing the legacies of colonialism that brought with it such things as patriarchy, eurocentrism, and structuralism. It has been feminist theory, queer theory, Indigenous peoples, and other marginalized groups who, over the past few years, have helped to draw attention to, and disrupt, what, in socio-cultural terms are often referred to as dominant discourses and grand narratives. These ways of describing the world and human experience tend to align with a Western ideology with embedded hierarchies and colonist world views. Historically, these narratives have served to advantage certain populations while pathologizing and further marginalizing others. The process of reconceptualizing is embraced as a way to move forward with social justice.

For more information check out Reconceptualizing Early Childhood Education.

Critical theory demands that we adopt a postmodern perspective of child development and encourages early educators to reexamine ideologies, beliefs, and assumptions and to question and look beyond the fixed views of children proposed by existing theories. In everyday practice, this may look like critically examining a storybook for any hidden political or social points of view ( e.g. gender, race, class) made through the stories and images. Posing questions such as whose story is this? Who gets to tell the story? Is it a true representation? Who has been left out? Educators are encouraged to engage in conversations with families and children about representations, a practice that lives into the four foundations of How Does Learning Happen?

In sum, postmodernism denies the existence of one objective view of child development but rather encourages multiple perspectives of viewing how children develop and learn.

Within the dominant discourse described above, the scientific method was lauded as the way to objectively quantify and describe the world, including human development and diversity. We are reconceptualizing science as one of many ways to describe and make meaning of the world and human experience. We are only here today because our ancestors survived and flourished for millennia. They shared their experiences across generations through oral tradition and art as examples.

Indigenous Perspectives

In Indigenous cultures, children are viewed as sacred gifts from the Creator and therefore their growth is seen as a spiritual journey of development and learning. The Medicine Wheel that symbolizes stages of life is used to represent this sacred journey. First Nation, Inuit, and Metis families are interdependent and with each stage of life, each member brings special gifts as well as responsibilities to the family and community. Elders, who are considered knowledge keepers, bring teachings from ancestors to help children understand their sacred place in the universe. Indigenous communities view child development as a journey that is closely bound by the natural and spiritual world and therefore the developing child is shaped by unique ways of knowing and teachings.

For further reading:

A child becomes strong: Journeying through each stage of the life cycle.

We are now beginning to embrace these ways of living in the world. One way to begin to integrate these world views is through ‘Two-Eyed Seeing’. This guiding principle refers to learning to see from one eye with the strengths of Indigenous knowledges and ways of knowing, and from the other eye with the strengths of Western knowledges and ways of knowing … and learning to use both these eyes together, for the benefit of all. Shared by Elder Albert Marshall in 2004 ‘Two-Eyed Seeing’ is the gift of multiple perspective treasured by many Indigenous peoples (Institute for Integrative Science and Health, n.d.), and refers to shifting from the Western binary dualism of ‘either/or’ to embracing the positive in both of these world views as ‘both/and’.

Please note that the above is not a critique of science. We do not have to look too far to see evidence of just how much science has contributed to global human health and well-being. It is about HOW science has been used to often deny rather than embrace human diversity.

Let’s take a look at some key theories in Child Development.

Sigmund Freud’s Psychosexual Theory

We begin with the often controversial figure, Sigmund Freud (1856-1939). Freud has been a very influential figure in the area of development; his view of development and psychopathology dominated the field of psychiatry until the growth of behaviourism in the 1950s. His assumptions that personality forms during the first few years of life and that the ways in which parents or other caregivers interact with children have a long-lasting impact on children’s emotional states have guided parents, educators, clinicians, and policy-makers for many years. We have only recently begun to recognize that early childhood experiences do not always result in certain personality traits or emotional states. There is a growing body of literature addressing resilience in children who experience trauma and yet develop without damaging emotional scars (O’Grady and Metz, 1987, as cited in Paris, Ricardo, Raymond, & Johnson, 2021). Freud has stimulated an enormous amount of research and generated many ideas. Agreeing with Freud’s theory in its entirety is hardly necessary for appreciating the contribution he has made to the field of development.

Table 1.3 Sigmund Freud’s Psychosexual Theory

| Name of Stage | Description of Stage |

| Oral Stage | The oral stage lasts from birth until around age 2. The infant is all id. At this stage, all stimulation and comfort is focused on the mouth and is based on the reflex of sucking. Too much indulgence or too little stimulation may lead to fixation. |

| Anal Stage | The anal stage coincides with potty training or learning to manage biological urges. The ego is beginning to develop in this stage. Anal fixation may result in a person who is compulsively clean and organized or one who is sloppy and lacks self-control |

| Phallic Stage | The phallic stage occurs in early childhood and marks the development of the superego and a sense of masculinity or femininity as culture dictates. |

| Latency | Latency occurs during middle childhood when a child’s urges quiet down and friendships become the focus. The ego and superego can be refined as the child learns how to cooperate and negotiate with others. |

| Genital Stage | The genital stage begins with puberty and continues through adulthood. Now the preoccupation is that of sex and reproduction. |

Strengths and Weaknesses of Freud’s Theory

Erik Erikson’s Psychosocial Theory

Erikson expanding on Freud’s theories by emphasizing the importance of culture in parenting practices and motivations and adding three stages of adult development (Erikson, 1950; 1968, as cited in Paris, Ricardo, Raymond, & Johnson, 2021).

Table 1.4 Erik Erikson’s Psychosocial Theory

| Name of Stage | Description of Stage |

| Trust vs. mistrust (0-1) | |

| Autonomy vs. shame and doubt (1-2) | Mobile toddlers have newfound freedom they like to exercise and by being allowed to do so, they learn some basic independence. |

| Initiative vs. Guilt (3-5) | |

| Industry vs. inferiority (6- 11) | School-aged children focus on accomplishments and begin making comparisons between themselves and their classmates |

| Identity vs. role confusion (adolescence) | Teenagers are trying to gain a sense of identity as they experiment with various roles, beliefs, and ideas. |

| Intimacy vs. Isolation (young adulthood) | In our 20s and 30s we are making some of our first long-term commitments in intimate relationships. |

| Generativity vs. stagnation (middle adulthood) | The 40s through the early 60s we focus on being productive at work and home and are motivated by wanting to feel that we’ve made a contribution to society. |

| Integrity vs. Despair (late adulthood) | We look back on our lives and hope to like what we see-that we have lived well and have a sense of integrity because we lived according to our beliefs. |

These eight stages form a foundation for discussions on emotional and social development during the life span. Keep in mind, however, that these stages or crises can occur more than once. For instance, a person may struggle with a lack of trust beyond infancy under certain circumstances. Erikson’s theory has been criticized for focusing so heavily on stages and assuming that the completion of one stage is a prerequisite for the next crisis of development. This theory also focuses on the social expectations that are found in certain cultures, but not in all. For instance, the idea that adolescence is a time of searching for identity might translate well in the middle-class culture of Canada, but not as well in cultures where the transition into adulthood coincides with puberty through rites of passage and where adult roles offer fewer choices (Lumen Learning, n.d.).

BehavioUrism

Ivan Pavlov

John B. Watson

B.F. Skinner and Operant Conditioning

Social Learning Theory

Jean Piaget’s Theory of Cognitive Development

Table 1.5 Piaget’s Theory of Cognitive Development

| Name of Stage | Description of Stage |

| Sensorimotor Stage | During the sensorimotor stage children rely on use of the senses and motor skills. From birth until about age 2, the infant knows by tasting, smelling, touching, hearing, and moving objects around. This is a real hands on type of knowledge. |

| Preoperational Stage | In the preoperational stage, children from ages 2 to 7, become able to think about the world using symbols. A symbol is something that stands for something else. The use of language, whether it is in the form of words or gestures, facilitates knowing and communicating about the world. This is the hallmark of preoperational intelligence and occurs in early childhood. However, these children are preoperational or pre-logical. They still do not understand how the physical world operates. They may, for instance, fear that they will go down the drain if they sit at the front of the bathtub, even though they are too big. |

| Concrete Operational | Children in the concrete operational stage, ages 7 to 11, develop the ability to think logically about the physical world. Middle childhood is a time of understanding concepts such as size, distance, and constancy of matter, and cause and effect relationships. A child knows that a scrambled egg is still an egg and that 8 ounces of water is still 8 ounces no matter what shape of glass contains it. |

| Formal Operational | During the formal operational stage children, at about age 12, acquire the ability to think logically about concrete and abstract events. The teenager who has reached this stage is able to consider possibilities and to contemplate ideas about situations that have never been directly encountered. More abstract understanding of religious ideas or morals or ethics and abstract principles such as freedom and dignity can be considered. |

Criticisms of Piaget’s Theory

Lev Vygotsky’s Sociocultural Theory

Comparing Piaget and Vygotsky

Indigenous Perspectives

Comparing Piaget and Vygotsky – both statements are right for indigenous culture, the child is seen as “actively discovering the world through individual interactions with it (children are encouraged to play outside) and, as more of an apprentice, learning through a social environment of others who had more experience and were sensitive to the child’s needs and abilities.” (Leon, n.d) Boys were around their mothers until the age of 7; subsequently, they would go with the men to learn the skills of protection and hunting (i.e. flint making, arrows, making nets, snowshoes, etc.) Today, in some families who are keeping the traditional ways of life alive, boys go hunting, trapping and, fishing with their father, a community member or another male relative; some as early as 7 or 8 for small game. When they reach the age of 11 or 12 they are encouraged to kill big game which is celebrated. They are encouraged to share the game with elders and/or other community members. Girls were traditionally taught skills such as cooking, tanning hides, putting up the teepee (or other forms of habitats), rearing children, fetching wood and water, as well as other chores. Today, it is not uncommon for girls to do the same as the boys with their father or with the whole family. Both girls and boys help with younger siblings, especially if there are many. Some of these may defer from nation to nation.

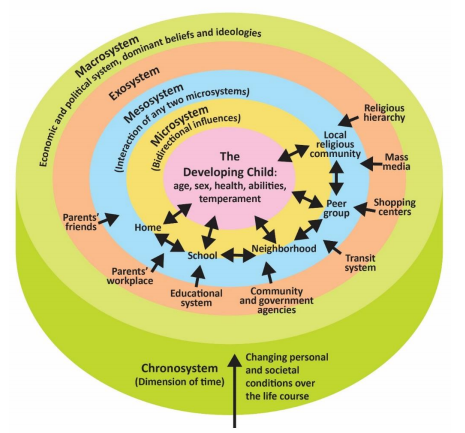

Urie Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Model

Table 1.6 Urie Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Model

| Name of the System | Description of System |

| Microsystems | Microsystems impact a child directly. These are the people with whom the child interacts such as parents, peers, and teachers. The relationship between individuals and those around them need to be considered. For example, to appreciate what is going on with a student in math, the relationship between the student and teacher should be known. |

| Mesosystems | Mesosystems are interactions between those surrounding the individual. The relationship between parents and schools, for example, will indirectly affect the child. |

| Exosystem | Larger institutions such as the mass media or the healthcare system are referred to as the exosystem. These have an impact on families and peers and schools that operate under policies and regulations found in these institutions. |

| Macrosystems | We find cultural values and beliefs at the level of macrosystems. These larger ideals and expectations inform institutions that will ultimately impact the individual. |

| Chronosystem | All of this happens in a historical context referred to as the chronosystem. Cultural values change over time, as do policies of educational institutions or governments in certain political climates. Development occurs at a point in time. |

Indigenous PerspectiveS

As for Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Model: it seems the same as the saying: It takes a community to raise a child. In some indigenous communities, the aunts and uncles are the ones who “discipline” children to keep harmony in the family. Discipline in the sense that they talk to the children when they are not contributing to the household or when they are giving their parents a hard time. It is common for children to go live with either aunts and uncles, or grandparents for periods of time to learn different skills, knowledge and/or teachings as well as to go help out with child-rearing. There is a strong sense of sharing our gifts from the Creator, the children, with our extended family. They are considered to be lent to us by the Creator.

Summary

In this chapter we looked at:

- underlying principles of development

- the five periods of development

- three issues in development

- various methods of research

- important theories that help us understand the development

References

Baker, D. B. & Sperry, H. (2021). History of psychology. In R. Biswas-Diener & E. Diener (Eds), Noba textbook series: Psychology. Champaign, IL: DEF publishers. Retrieved from http://noba.to/j8xkgcz5

Bisnaine, L., Clinton, J., & Ferguson, B. (2014). Understanding the whole child and youth; A key to learning. Retrieved from http://www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/policyfunding/leadership/spring2014.pdf

Canadian Psychological Association. (2017). Canadian Code of Ethics for Psychologists (4th Ed.). Ottawa, ON: Canadian Psychological Association. Retrieved from https://cpa.ca/docs/File/Ethics/CPA_Code_2017_4thEd.pdf

College of Early Childhood Educators. (2017). Code of ethics and standards of practice for early childhood educators in Ontario. Retrieved from https://www.college-ece.ca/en/documents/code_and_standards_2017.pdf

Institute for Integrative Science and Health (n.d.). Two-eyed seeing. Retrieved from http://www.integrativescience.ca/Principles/TwoEyedSeeing/

Lally, M. & Valentine-French, S. (2019). Lifespan development: A psychological perspective. Retrieved from http://dept.clcillinois.edu/psy/LifespanDevelopment.pdf

Leon, A. (n.d.). Children’s development: Prenatal through adolescent development. Retrieved from https://docs.google.com/document/d/1k1xtrXy6j9_NAqZdGv8nBn_I6-lDtEgEFf7skHjvE-Y/edit

Lukowski, A. & Milojevich, H. (2021). Research methods in developmental psychology. In R. Biswas-Diener & E. Dinner (Eds), Noba textbook series: Psychology. Champaign, IL: DEF publishers. Retrieved from https://nobaproject.com/modules/research-methods-in-developmental-psychology

Lumen Learning. (n.d.). Introduction to lifespan, growth and development. Retrieved from https://courses.lumenlearning.com/lifespandevelopment2/

Mustard, J. F. (2006). Early child development and experience-based brain development: The scientific underpinnings of the importance of early child development in a globalized world. Washington, DC: Brookings Institute.

Ontario Ministry of Education. (2014a). Excerpts from ELECT: Foundational knowledge from the 2007 publication of “Early learning for every child today: A framework for Ontario early childhood settings”. Retrieved from https://www.dufferincounty.ca/sites/default/files/rtb/Excerpts-from-Early-Learning-for-Every-Child-Today.pdf

Ontario Ministry of Education. (2014b). How does learning happen? Ontario’s pedagogy for the early years: A resource about learning through relationships for those who work with young children and their families. Retrieved from https://files.ontario.ca/edu-how-does-learning-happen-en-2021-03-23.pdf

Overstreet, L. (n.d.). Psyc 200 lifespan psychology. Retrieved from: http://opencourselibrary.org/econ-201/.

Rasmussen, E. (2017). Screen time and kids: Insights from a new report. Retrieved from https://www.pbs.org/parents/thrive/screen-time-and-kids-insights-from-a-new-report