5 Cognitive Development in Infancy and Toddlerhood

Chapter Objectives

After this chapter, you should be able to:

- Describe the substages of the Piaget’s sensorimotor stage.

- Explain how the social environment affects cognitive development according to Vygotsky’s theory.

- Define classical and operant conditioning.

- Summarize the different types of memory.

INTRODUCTION

Infant and toddler development is rapid and complex, and cognitive development is no exception. Cognitive development includes such skills as maintaining attention, problem solving, memory and representation. You will find details of these skills and their indicators in Domain 4 in the Continuum of Development (Ontario Ministry of Education, 2014). Several theorists have contributed to our understanding of human cognition. They include: Piaget, Vygotsky, Chomsky, Skinner, Pavlov, Watson, Bandura, and Bronfenbrenner. In this chapter we will explore and analyze their perspectives.

In Chapter One, you were introduced to Jean Piaget’s perspectives on human cognitive development. Piaget is the most noted theorist when it comes to children’s cognitive development. He believed that children’s cognition develops in stages.

He explained this growth in the following stages:

- Sensory Motor Stage (Birth through 2 years old) with 6 substages detailed below.

- Preoperational Stage (2-7 years old)

- Concrete Operational Stage (7-11 years old)

- Formal Operational Stage (12 years old- adulthood)

In this cognitive chapter we will focus on his first stage which occurs in infancy (Leon, n.d.). We will also examine more closely the aspects of his theories that apply to cognitive development during infancy and toddlerhood. These include the six substages of sensorimotor development, schemas, assimilation, accommodation, equilibrium, disequilibrium and object permanence.

Piaget was one of the first theorists to map out and describe the ways in which children’s thought processes differ from those of adults. More specifically he identified that children of differing ages interpreted the world differently. He stressed that cognitive development occurs through constant interaction between their maturation and their experiences of the world. This interaction piece represented new thinking. Piaget believed that children were naturally curious. They want to make sense of their experiences, and in doing so, construct their understanding of the world. They are like scientists and construct theories about the world. Of course, these theories are often incomplete but they help them to reach more advanced levels of maturation. The theories also help to make the world more predictable. Piaget identified that knowledge and understanding moves from physical or concrete understanding of abstract thinking.

One of the mechanisms that children use to understand the world is through schemas. A schema is a psychological structure to organize information. We can think of this as a mental category or a conceptual model of interrelated events, objects or knowledge that children build as they gain experience. They learn how aspects of their world relate to each other. They collect this knowledge together in schemas which help them to navigate events and relationships. In infancy most schemas relate to their own actions….How can I control my body? How do parts of my body relate to each other? How can I use my body to manipulate objects? For example, infants eventually learn how to control their hands to interact with objects external to them. Then children’s thinking and understanding increases in complexity as they learn that the world can be represented through words, gestures, objects and concepts.

Assimilation and accommodation

These two processes, identified by Piaget, work together. Assimilation occurs when new experiences are incorporated into the existing schemas. Infants whose schemas are about their actions may have a schema for grasping. They understand that grasping is an effective action for picking up toys, and they learn that this action also works for other things as well such as food. When they encounter a situation where the schema doesn’t work, based on experience, they modify it. For example, they learn that some objects can be lifted with one hand while other objects are larger or heavier and require two hands to move them. These examples illustrate Piaget’s perspective that learning occurs through interaction between maturity and their experiences of the world.

In their cognitive development children frequently encounter situations where it is simply not possible to assimilate an experience into an existing schema or category. In this situation a new schema has to be developed. Piaget used the term accommodation to describe this mental process.

Perhaps a child’s family has a dog. The infant develops a schema for ‘dog’. This includes information about the dog including physical characteristics such four legs, a tail, fur, the food it eats and its name. Then the child meets a neighbour’s dog. The child observes that the dog does not look exactly like their family dog and learns that it has a different name than their family pet, but they can readily make these mental adjustments and add the neighbour’s dog into their schema for dogs. One day, when out on a walk in the neighbourhood the child sees a cat sunning itself in a driveway. They observe that this creature has four legs, a tail and is covered in fur and the child accessing their schema for dogs, points to the cat and says ‘Dog!’ The family explains that this is not a dog, but rather a cat. In this case this new information cannot be assimilated into the existing schema for dogs so a new category is created for cats. The child would add information about the characteristics of cats, the fact that they are pets, they are given names and eat special food. This is an example of accommodation. New experiences of cats and dogs will continue to be assimilated into these schemas and the child will create new schemas to organize information about other animals.

Piaget described equilibrium as a period when accommodation and assimilation are usually in balance but sometimes more time is spent on accommodating than assimilating. The balance is upset and he referred to this as disequilibrium. This occurs when outmoded ways of thinking are replaced by more advanced schemas. As far as theories, they may find a critical flaw in their theory making it no longer effective to make predictions about the world. It is time to develop a new theory. This happens at three different times over the life span at age 2, 7 and 11. Piaget identified 4 stages of cognitive development which all children go through in sequence. Each stage is marked by a distinct way of understanding the world.

Object Permanence

Object permanence refers to the understanding that objects exist independent of one’s self and one’s actions.

This understanding takes place over time.

- 1-4: months an object disappears from view then it no longer exists

- 8-10: understanding is incomplete…if a child sees an object under container 1 and then under container 2. The child will look under container 1 even if they can see the outline of the object under contain 2. The child does not distinguish between the actual object and the actions they used to locate it such as lifting the container.

- At 12 months: child will look for the object in several different locations

- At 18 months: they understand that an object is moved it still exists (e.g. parent tidies up toys while child is sleeping)

There have been minor revisions made to Piaget’s theory, for example, Baillargeon (1987) demonstrated that infants understand objects much earlier than Piaget claimed. Some of Piaget’s observations and findings could have been more about memory and not about an understanding of objects and that this understanding may occur earlier than Piaget believed. It does not mean that his theory was fundamentally wrong, just that it may need some revision.

Piaget and Sensorimotor Intelligence

Piaget describes intelligence in infancy as sensorimotor or based on direct, physical contact. Infants taste, feel, pound, push, hear, and move in order to experience the world. Let’s explore the transition infants make from responding to the external world reflexively as newborns to solving problems using mental strategies as two years old. Piaget identified six substages with in the sensorimotor stage of development. These sub stages represent a distinct way of representing the world. While Piaget maintained that all children move through the stages in order, the age ages may vary from child to child. Thus, the ages listed in the table below are only approximate.

Piaget’s Six Stages of Sensorimotor Development

| Substage | Age (months) | Accomplishments | Examples |

| 1 | 0-1 | Reflexes become coordinated | Sucking a nipple |

| 2 | 1-4 | Primary circular reactions appear. First learned adaptations to the world | Thumb sucking. This active learning begins with automatic movements or reflexes. A ball comes into contact with an infant’s cheek and is automatically sucked on and licked. |

| 3 | 4-8 | Secondary circular reactions emerge allowing children to learn about the world | Shaking a toy to hear it rattle in being able to make things happen. Repeated motion brings particular interest as the infant is able to bang two lids together from the cupboard when seated on the kitchen floor. |

| 4 | 8-12 | Means-end sequencing develops making the onset of intentional behaviour | The infant can engage in behaviours that others perform and anticipate upcoming events. Perhaps because of continued maturation of the prefrontal cortex, the infant becomes capable of having a thought and carrying out a planned goal directed activity such as seeking a toy that has rolled under the couch. The object continues to exist in the child’s mind even when out of sight and the infant is now capable of making attempts to retrieve it. |

| 5 | 12-18 | Tertiary circular reactions appear. allowing children to experiment with new behaviours. | Shaking different toys to hear the sounds they make. |

| 6 | 18-24 | Metal representations of the world |

Deferred imitation, the beginning of make-believe play

The infant more actively engages in experimentation to learn about the physical world. Gravity is learned by pouring water from a cup or pushing bowls from high chairs. The caregiver tries to help the child by picking it up again and placing it on the tray. And what happens? Another experiment! The child pushes it off the tray again causing it to fall and the caregiver to pick it up again!

The child is now able to solve problems using mental strategies, to remember something heard days before and repeat it, to engage in pretend play, and to find objects that have been moved even when out of sight. Take for instance, the child who is upstairs in a room with the door closed, supposedly taking a nap. The doorknob has a safety device on it that makes it impossible for the child to turn the knob. After trying several times in vain to push the door or turn the doorknob, the child carries out a mental strategy learned from prior experience to get the door opened-he knocks on the door! The child is now better equipped with mental strategies for problem-solving. |

Table 5.1: Piaget’s Six Stages of Sensorimotor Development (Paris, Ricardo, Raymond, & Johnson, 2021)

Evaluating Piaget’s Sensorimotor Stage

Piaget opened up a new way of looking at infants with his view that their main task is to coordinate their sensory impressions with their motor activity. However, the infant’s cognitive world is not as neatly packaged as Piaget portrayed it, and some of Piaget’s explanations for the cause of change are debated. In the past several decades, sophisticated experimental techniques have been devised to study infants, and there have been a large number of many research studies on infant development. Much of the new research suggests that Piaget’s view of sensorimotor development needs to be modified (Baillargeon, 2014; Brooks & Meltzoff, 2014; Johnson & Hannon, 2015, as cited in Paris, Ricardo, Raymond, & Johnson, 2021).

Object Permanence

One necessary modification would be when children develop object permanence. Infants seem to be able to recognize that objects have permanence at much younger ages than Piaget proposed (even as young as 3.5 months of age).

The A-not-B Error

The data collected in more contemporary research (see examples below) does not always support Piaget’s claim that certain processes are crucial in transitions from one stage to the next. For example, in Piaget’s theory, an important feature in the progression into substage 4, coordination of secondary circular reactions, is an infant’s inclination to search for a hidden object in a familiar location rather than to look for the object in a new location. Thus, if a toy is hidden twice, initially at location A and subsequently at location B, 8- to 12-month-old infants search correctly at location A initially. But when the toy is subsequently hidden at location B, they make the mistake of continuing to search for it at location A. A-not B error is the term used to describe this common mistake. Older infants are less likely to make the A-not-B error because their concept of object permanence is more complete. Researchers have found, however, that the A-not B error does not show up consistently (Sophian, 1985, as cited in Paris, Ricardo, Raymond, & Johnson, 2021). The evidence indicates that A-not-B errors are sensitive to the delay between hiding the object at B and the infant’s attempt to find it (Diamond, 1985, as cited in Paris, Ricardo, Raymond, & Johnson, 2020). Thus, the A-not-B error might be due to a failure in memory. Another explanation is that infants tend to repeat a previous motor behaviour (Clearfield & others, 2006; Smith, 1999, as cited in Paris, Ricardo, Raymond, & Johnson, 2021).

Vygotsky: Development is Determined By Environmental Factors

Piaget certainly developed many theories during his career, but they have also received a great deal of criticism. Many believe that Piaget ignored the significant influence that society and culture have in shaping a child’s development. Lev Vygotsky (1896–1934), another child development researcher working at the same time as Piaget. He had come to similar conclusions as Piaget about children’s development, in thinking that children learned about the world through physical interaction with it. However, where Piaget felt that children moved naturally through different stages of development, based on biological predispositions and their own individual interactions with the world, Vygotsky claimed that adult or peer intervention was a much more important part of the developmental process. Vygotsky concentrated more on the child’s immediate social and cultural environment and his or her interactions with adults and peers. He argued that development occurred first through children’s immediate social interactions, and then moved to the individual level as they began to internalize their learning. While Piaget saw the child as actively discovering the world through individual interactions with it, Vygotsky saw the child as more of an apprentice, learning through a social environment of others who had more experience and were sensitive to the child’s needs and abilities (Leon, n.d.).

When infants, children and adults are presented with a strong or unfamiliar stimulus, an orienting response usually occurs. The person reacts, looks at the stimulus and experiences changes in heart rate and brain wave activity. These indicate that the person has noticed the stimulus. After repeated presentations they become familiar with it and the response disappears. This is referred to as habituation. For newly born infants everything in their environment is unfamiliar, the doorbell, the dog barking, the television as examples. The infant may react to these stimuli, however, within a few days an infant may appear to hardly notice them. This means they have become accustomed to them.

Dishabituation occurs when a person becomes actively aware of the stimulus again. Orientation is important to keep us safe, but constantly responding to an insignificant stimulus is unnecessary so habituation keeps infants from wasting energy on insignificant events (Rovee-Collier, 1987). An infant may start to lose interest in playing peek a boo, but if you change the object that is hiding or the expression on your face they may become interested again.

theories of cognitive development, learning and memory

Pavlov

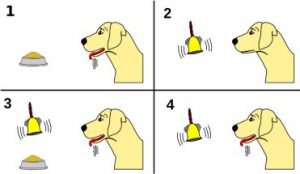

Ivan Pavlov (1880-1937) was a Russian physiologist interested in studying digestion. As he recorded the amount of salivation his laboratory dogs produced as they ate, he noticed that they actually began to salivate before the food arrived as the researcher walked down the hall and toward the cage. The dogs knew that the food was coming because they had learned to associate the footsteps with the food. The keyword here is “learned”. A learned response is called a “conditioned” response.

Pavlov began to experiment with this “psychic” reflex. He began to ring a bell, for instance, prior to introducing the food. Sure enough, after making this connection several times, the dogs could be made to salivate to the sound of a bell. Once the bell had become an event to which the dogs had learned to salivate, it was called a conditioned stimulus. The act of salivating to a bell was a response that had also been learned, now termed in Pavlov’s jargon, a conditioned response.

Notice that the response, salivation, is the same whether it is conditioned or unconditioned (unlearned or natural). What changed is the stimulus to which the dog salivates. One is natural (unconditioned) and one is learned (conditioned).

Figure 5.1: Pavlov’s experiments with dogs and conditioning. (Image by Maxxl² is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0)

Classical Conditioning

Classical conditioning is a form of learning whereby a conditioned stimulus (CS) becomes associated with an unrelated unconditioned stimulus (US), in order to produce a behavioural response known as a conditioned response (CR). The conditioned response is the learned response to the previously neutral stimulus. The unconditioned stimulus is usually a biologically significant stimulus such as food or pain that elicits an unconditioned response (UR) from the start. The conditioned stimulus is usually neutral and produces no particular response at first, but after conditioning, it elicits the conditioned response.

If we look at Pavlov’s experiment, we can identify these four factors at work:

- The unconditioned response was the salivation of dogs in response to seeing or smelling their food. The unconditioned stimulus was the sight or smell of the food itself.

- The conditioned stimulus was the ringing of the bell. During conditioning, every time the animal was given food, the bell was rung. This was repeated during several trials. After some time, the dog learned to associate the ringing of the bell with food and to respond by salivating.

- After the conditioning period was finished, the dog would respond by salivating when the bell was rung, even when the unconditioned stimulus (the food) was absent.

- The conditioned response, therefore, was the salivation of the dogs in response to the conditioned stimulus (the ringing of the bell) (Leon, n.d.).

Neurological Response to Conditioning

Consider how the conditioned response occurs in the brain. When a dog sees food, the visual and olfactory stimuli send information to the brain through their respective neural pathways, ultimately activating the salivary glands to secrete saliva. This reaction is a natural biological process as saliva aids in the digestion of food. When a dog hears a buzzer and at the same time sees food, the auditory stimuli activate the associated neural pathways. However, since these pathways are being activated at the same time as the other neural pathways, there are weak synapse reactions that occur between the auditory stimuli and the behavioural response. Over time, these synapses are strengthened so that it only takes the sound of a buzzer to activate the pathway leading to salivation.

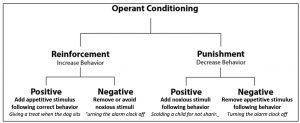

Operant Conditioning

Operant conditioning is a theory of behaviourism, a learning perspective that focuses on changes in an individual’s observable behaviours. In operant conditioning theory, new or continued behaviours are impacted by new or continued consequences. Research regarding this principle of learning was first studied by Edward L. Thorndike in the late 1800’s, then brought to popularity by B.F. Skinner in the mid-1900’s. Much of this research informs current practices in human behaviour and interaction.

Skinner’s Research

Thorndike’s initial research was highly influential on another psychologist, B.F. Skinner. Almost half a century after Thorndike’s first publication of the principles of operant conditioning, Skinner attempted to prove an extension to this theory—that all behaviours were in some way a result of operant conditioning. Skinner theorized that if a behaviour is followed by reinforcement, that behaviour is more likely to be repeated, but if it is followed by punishment, it is less likely to be repeated. He also believed that this learned association could end, or become extinct if the reinforcement or punishment was removed. To prove this, he placed rats in a box with a lever that when tapped would release a pellet of food. Over time, the amount of time it took for the rat to find the lever and press it became shorter and shorter until finally, the rat would spend most of its time near the lever eating. This behaviour became less consistent when the relationship between the lever and the food was compromised. This basic theory of operant conditioning is still used by psychologists, scientists, and educators today.

Shaping, Reinforcement Principles, and Schedules of Reinforcement

Operant conditioning can be viewed as a process of action and consequence. Skinner used this basic principle to study the possible scope and scale of the influence of operant conditioning on animal behaviour. His experiments used shaping, reinforcement, and reinforcement schedules in order to prove the importance of the relationship that animals form between behaviours and results. All of these practices concern the setup of an experiment. Shaping is the conditioning paradigm of an experiment. The form of the experiment in successive trials is gradually changed to elicit a desired target behaviour. This is accomplished through reinforcement, or reward, of the segments of the target behaviour, and can be tested using a large variety of actions and rewards. The experiments were taken a step further to include different schedules of reinforcement that become more complicated as the trials continued. By testing different reinforcement schedules, Skinner learned valuable information about the best ways to encourage a specific behaviour, or the most effective ways to create a long-lasting behaviour. Much of this research has been replicated on humans, and now informs practices in various environments of human behaviour (Leon, n.d.).

Positive and Negative Reinforcement

Positive reinforcement involves adding something to the situation in order to encourage a behaviour. Other times, taking something away from a situation can be reinforcing. For example, the loud, annoying buzzer on your alarm clock encourages you to get up so that you can turn it off and get rid of the noise. Children whine in order to get their parents to do something and often, parents give in just to stop the whining. In these instances, negative reinforcement has been used.

Figure 5.2: Reinforcement in operant conditioning. (Image by Curtis Neveu is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 and Modified from source image)

Operant conditioning tends to work best if you focus on trying to encourage a behaviour or move a person into the direction you want them to go rather than telling them what not to do. Reinforcers are used to encourage a behaviour; punishers are used to stop behaviour. A punisher is anything that follows an act and decreases the chance it will reoccur. But often a punished behaviour doesn’t really go away. It is just suppressed and may reoccur whenever the threat of punishment is removed.

Perhaps a family feels very strongly about swearing and the children have lost privileges such as a special treat or an outing because they have used inappropriate language in the house. However, when the children are with their peers and out of earshot they frequently use swearwords in their speech.

Think of human behaviour in general. Many drivers, including those who have received speeding tickets in the past, go over the posted speed limit and are more likely to do this if they do not perceive the presence of police or a device to monitor speed.

Another problem with punishment is that when a person focuses on punishment, they may find it hard to see what the other does right or well. And punishment is stigmatizing; when punished, some start to see themselves as bad and give up trying to change.

Reinforcement can occur in a predictable way, such as after every desired action is performed, or intermittently, after the behaviour is performed a number of times or the first time it is performed after a certain amount of time. The schedule of reinforcement has an impact on how long a behaviour continues after reinforcement is discontinued. So a parent who has rewarded a child’s actions each time may find that the child gives up very quickly if a reward is not immediately forthcoming. Think about the kinds of behaviours that may be learned through classical and operant conditioning. But sometimes very complex behaviours are learned quickly and without direct reinforcement. Bandura’s Social Learning covered later in the chapter explains how.

Watson and Behaviourism

Another theorist who added to the spectrum of the behavioural movement was John B. Watson. Watson believed that most of our fears and other emotional responses are classically conditioned. He had gained a good deal of popularity in the 1920s with his expert advice on parenting offered to the public. He believed that parents could be taught to help shape their children’s behaviour and tried to demonstrate the power of classical conditioning with his famous experiment with an 18-month-old boy named “Little Albert”. Watson sat Albert down and introduced a variety of seemingly scary objects to the child: a burning piece of newspaper, a white rat, etc. But Albert remained curious and reached for all of these things. Watson knew that one of our only inborn fears is the fear of loud noises so he proceeded to make a loud noise each time he introduced one of Albert’s favourites, a white rat. After hearing the loud noise several times paired with the rat, Albert soon came to fear the rat and began to cry when it was introduced.

Watson filmed this experiment for posterity and used it to demonstrate that he could help parents achieve any outcomes they desired, if they would only follow his advice. Watson wrote columns in newspapers and in magazines and gained a lot of popularity among parents eager to apply science to household order. Parenting advice was not the legacy Watson left us, however. Where he really made his impact was in advertising. After Watson left academia, he went into the world of business and showed companies how to tie something that brings about a natural positive feeling to their products to enhance sales. For example, in advertising products are often intentionally aligned with images of attractive models engaging in appealing activities. Sometimes we do things because we’ve seen it pay off for someone else. They were operantly conditioned, but we engage in the behaviour because we hope it will pay off for us as well. This is referred to as vicarious reinforcement (Bandura, Ross and Ross, 1963, as cited in Paris, Ricardo, Raymond, & Johnson, 2021).

Figure 5.3: A photograph taken during Little Albert research. (Image is in the public domain)

Do parents socialize children or do children socialize parents?

Bandura (1986) suggests that there is interplay between the environment and the individual. We are not just the product of our surroundings, rather we influence our surroundings. There is interplay between our personality and the way we interpret events and how they influence us. This concept is called reciprocal determinism. An example of this might be the interplay between parents and children. Parents not only influence their child’s environment, perhaps intentionally through the use of reinforcement, etc., but children influence parents as well. Parents may respond differently with their first child than with their fourth. Perhaps they try to be the perfect parents with their firstborn, but by the time their last child comes along they have very different expectations both of themselves and their child. Our environment creates us and we create our environment.

Goodness of fit

Figure 5.4: A smiling infant playing with toys. (Image by OmarMedinaFilms on Pixabay)

A child’s temperament will influence how the caregivers respond to them. Thomas, Chess, & Birch (1985) identified three temperaments – easy, difficult and slow to warm up.

Goodness of fit is a term borrowed from statistics to describe the compatibility between a person’s temperament and their surrounding environment. There are two aspects involved: how the trait interacts with the environment and how it interacts with the people in that environment. Any trait itself is not a problem, but it is the degree to which that trait is accepted that determines the goodness of fit. When the child’s temperament, skills and abilities match the expectations of the environment well this supports success and positive self-esteem. Difficulties can result when there is not a good fit. Examples: a naturally active child who lives in a small apartment compared to a child who lives in a larger home with a large back yard (Center for Parenting Education, n.d.).

Indigenous Perspective

A toddler’s responsibility is about safety. As they explore the world around them, they like touching everything; hence learning through their interactions with the environment. Indigenous children are encouraged to explore the environment around them; especially outdoors to further their connection to the land.

When it comes to the fit with people in the child’s world, sometimes it is challenging for families, caregivers and educators to understand traits which differ greatly from themselves or traits which remind them about aspects of themselves that they do not like or that have been problematic in their lives. Examples: a child who does not enjoy physical activity in a family that does or a child who has a slow to warm up temperament (Thomas, Chess & Birch, 1985) in a family where members are very social and enjoy parties and social gatherings.

Social Learning Theory

Albert Bandura is a leading contributor to social learning theory. He calls our attention to the ways in which many of our actions are not learned through conditioning; rather, they are learned by watching others. Young children frequently learn behaviours through imitation. Sometimes, particularly when we do not know what else to do, we learn by modelling or copying the behaviour of others. A new employee, on his or her first day of a new job might eagerly look at how others are acting and try to act the same way to fit in more quickly. Adolescents struggling with their identity rely heavily on their peers to act as role-models. Newly married couples often rely on roles they may have learned from their parents and begin to act in ways they did not while dating and then wonder why their relationship has changed.

memory and attention

If we want to remember something tomorrow, we have to consolidate it into long-term memory today. Long-term memory is the final, semi-permanent stage of memory. Unlike sensory and short-term memory, long-term memory has a theoretically infinite capacity, and information can remain there indefinitely. Long-term memory has also been called reference memory, because an individual must refer to the information in long-term memory when performing almost any task. Long-term memory can be broken down into two categories: explicit and implicit memory.

Explicit Memory

Explicit memory, also known as conscious or declarative memory, involves memory of facts, concepts, and events that require conscious recall of the information. In other words, the individual must actively think about retrieving the information from memory. This type of information is explicitly stored and retrieved—hence its name. Explicit memory can be further subdivided into semantic memory, which concerns facts, and episodic memory, which concerns primarily personal or autobiographical information.

Episodic Memory

Episodic memory is used for more contextualized memories. They are generally memories of specific moments, or episodes, in one’s life. As such, they include sensations and emotions associated with the event, in addition to the who, what, where, and when of what happened. An example of an episodic memory would be recalling your family’s trip to the beach. Autobiographical memory (memory for particular events in one’s own life) is generally viewed as either equivalent to or a subset of episodic memory. One specific type of autobiographical memory is a flashbulb memory, which is a highly detailed, exceptionally vivid “snapshot” of the moment and circumstances in which a piece of surprising and consequential (or emotionally arousing) news was heard. For example, many people remember exactly where they were and what they were doing when they heard of the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001. This is because it is a flashbulb memory.

Semantic and episodic memory are closely related; memory for facts can be enhanced with episodic memories associated with the fact, and vice versa. For example, the answer to the factual question “Are all apples red?” might be recalled by remembering the time you saw someone eating a green apple. Likewise, semantic memories about certain topics, such as football, can contribute to more detailed episodic memories of a particular personal event, like watching a football game. A person that barely knows the rules of football will remember the various plays and outcomes of the game in much less detail than a football expert.

Implicit Memory

In contrast to explicit (conscious) memory, implicit (also called “unconscious” or “procedural”) memory involves procedures for completing actions. These actions develop with practice over time. Athletic skills are one example of implicit memory. You learn the fundamentals of a sport, practice them over and over, and then they flow naturally during a game. Rehearsing for a dance or musical performance is another example of implicit memory. Everyday examples include remembering how to tie your shoes, drive a car, or ride a bicycle. These memories are accessed without conscious awareness—they are automatically translated into actions without us even realizing it. As such, they can often be difficult to teach or explain to other people. Implicit memories differ from the semantic scripts described above in that they are usually actions that involve movement and motor coordination, whereas scripts tend to emphasize social norms or behaviours.

Figure 5.5: A toddler walking. (Image on Public Domain Pictures)

Short-Term Memory Storage

Short-term memory is the ability to hold information for a short duration of time (on the order of seconds). In the process of encoding, information enters the brain and can be quickly forgotten if it is not stored further in the short-term memory. George A. Miller (n.d., as cited in Paris, Ricardo, Raymond, & Johnson, 2021) suggested that the capacity of short-term memory storage is approximately seven items plus or minus two, but modern researchers are showing that this can vary depending on variables like the stored items’ phonological properties. When several elements (such as digits, words, or pictures) are held in short-term memory simultaneously, their representations compete with each other for recall, or degrade each other. Thereby, new content gradually pushes out older content, unless the older content is actively protected against interference by rehearsal or by directing attention to it.

Information in the short-term memory is readily accessible, but for only a short time. It continuously decays, so in the absence of rehearsal (keeping information in short-term memory by mentally repeating it) it can be forgotten.

Figure 5.6: Diagram of the memory storage process. (Image by Wikipedia is licensed under CCBY-SA3.0)

Long-Term Memory Storage

In contrast to short-term memory, long-term memory is the ability to hold semantic information for a prolonged period of time. Items stored in short-term memory move to long-term memory through rehearsal, processing, and use. The capacity of long-term memory storage is much greater than that of short-term memory, and perhaps unlimited. However, the duration of long-term memories is not permanent; unless a memory is occasionally recalled, it may fail to be recalled on later occasions. This is known as forgetting.

Long-term memory storage can be affected by traumatic brain injury or lesions. Amnesia, a deficit in memory, can be caused by brain damage. Anterograde amnesia is the inability to store new memories; retrograde amnesia is the inability to retrieve old memories. These types of amnesia indicate that memory does have a storage process (Leon, n.d.).

Information Processing theory

Infants learn to process information fairly quickly. When they are first brought home, everything is new and startling: the family dog, the doorbell, the television as examples. However, within a few days the infant may hardly seem to notice them and may even sleep through such sounds. They have learned to ignore sounds which had once startled them. This capacity helps to reduce stress and preserve energy for other tasks.

Information Processing Approach

This is an approach to human cognition which makes a distinction between computer hardware and computer software. This approach arose in the 1960s and is now considered a useful one to explain human cognition (Kail & Bisanz, 1992, as cited in Paris, Ricardo, Raymond, & Johnson, 2021).

This approach sees human thinking as based on both mental hardware and mental software.

Mental hardware refers to neural structures that are built in and allow the mind to operate. Mental hardware has three components: sensory memory, working memory and long-term memory.

Sensory memory refers to information which is held in a raw and unanalyzed form, literally for a few seconds.

Working memory is the site of ongoing cognitive activity. Some theorists compare this to a carpenter’s bench where there is space for storing materials as well as space to work with them (sawing, nailing, gluing etc.) (Klatzky, 1980).

Long term memory refers to the limitless, permanent storage of knowledge of the world. It is like a computer’s hard drive. Our long term memory stores facts (Ottawa is the capital of Canada), personal information (my neighbours have a new dog), and skills (how to ride a bike).

Some researchers have noted other forms of memory which include:

- procedural memory which is memory of how to do things

- semantic memory which is memory for particular facts

- autobiographical memory which is memory for specific events which have occurred for an individual.

Infantile Amnesia

While memory begin in infancy, children, adolescents and adults report remembering little from the first few years of life (Kail, 1990) What is your earliest memory? Do you truly remember this or is it more about having heard family members speak about it? If you recall a memory from when you were around three or four years of age then you have a typical capacity to remember memory (for example Eacott,1999). Most individuals are unable to report a memory form before this age. This inability to remember events from early in one’s life is referred to as infantile amnesia. Very early memories of events may arise because we have heard others speak of them or from seeing images such as photographs for videos.

Explaining Infantile Amnesia

Language Acquisition: There is a significant language component to memory where language is used to represent past events (Nelson, 1993, as cited in Paris, Ricardo, Raymond, & Johnson, 2021). Events which occurred in a prelingual stage may be difficult for an individual to retrieve.

Sense of self: It takes time for children’s sense of self to develop. Children under the age of three years may not yet an organized sense of self which acts as a framework for organizing memories of events from their own live (Harley & Reese, 1999; Howe & Courage, 1997, as cited in Paris, Ricardo, Raymond, & Johnson, 2021).

Culture: Other research (e.g. Wang, Conway & Hou, 2007) has identified a cultural component in experiences of infantile amnesia. These researchers found that in cultures which have a relational sense of self such as Chinese cultures where collective identities are valued, individuals tended to have longer periods of infantile amnesia. In contrast cultures that promote autonomy and an individualized sense of self, tend to see shorter periods of infantile amnesia and individuals reporting more early childhood memories.

Early memories: It is a common practice in many societies to practice family planning and space the birth of children. This often results in a child becoming a sibling for the first time between the ages of two and three years of age. The birth of a sibling is often reported as a dramatic event in one’s life and the ‘bringing home’ of a sibling is a commonly reported first memory. The event is dramatic, and the timing may align the development language and a sense of self, the conditions for organizing memories.

Summary

- Piaget’s sensorimotor stage.

- The impact of the social environment on children’s learning.

- The progression and theories of language development.

- Classical and operant conditioning and systems of reinforcement.

- The types of memory and how they work together.

References

Baillargeon, R. (1987). Object permanence in 3.5 and 4.5-month-old infants. Developmental Psychology, 23: 655–664.

Center for Parenting Education. (n.d) Understanding “Goodness of Fit”. Retrieved from https://centerforparentingeducation.org/library-of-articles/child-development/understanding-goodness-of-fit/

Eacott, M.J. (1999). Memory for the events of early childhood. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 8, 46-49.

Kail, R. (1990). The development of memory in children (3rd ed.). New York, NY: W.H. Freeman.

Kail, R. & Bisanz, J. (1992). The information processing perspective on cognitive development in childhood and adolescence. In R.J. Sternberg & A. Berg (Eds.) Intellectual development. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Klatzky, R.L. (1980). Human Memory (2nd ed.) San Francisco, CA: Freeman.

Ontario Ministry of Education. (2014). Excerpts from “Elect”. Retrieved from https://www.dufferincounty.ca/sites/default/files/rtb/Excerpts-from-Early-Learning-for-Every-Child-Today.pdf

Rovee-Collier, C. (1987). Learning and memory in infancy. In J. D. Osofsky (Ed.), Handbook of infant development (pp. 98–148). John Wiley & Sons.

Thomas, A. Chess, S. & Birch, H.G. (1985). Temperament and behavior disorders in children. New York, NY: University Press.

Wang, Q., Conway, M., & Hou, Y. (2007). Infantile amnesia: A cross-cultural investigation. In M.K. Sun (Ed.), New research in cognitive sciences (pp. 95-104). Hauppauge, NY: Nova Science.