4 Physical Development in Infancy and Toddlerhood

Chapter Objectives

After this chapter, you should be able to:

- Describe the physical changes that occur during the first two years of life.

- Identify common infant reflexes.

- Discuss the sleep needs during the first two years of life.

- Summarize the sequence of both fine and gross motor skills.

- Recognize the developing sensory capacities of infants and toddlers.

- Explain how to meet the evolving nutritional needs of infants and toddlers.

Introduction

Welcome to the story of physical development from infancy through toddlerhood; in Ontario the Continuum of Development considers infants ranging in age from birth to 24 months, and toddlers from 14 months to 3 years of age (Ontario Ministry of Education, 2014). When referring to infants and toddlers together in this text, we will focus on children less than 30 months old. Researchers have given this part of the life span more attention than any other period, perhaps because changes during this time are so dramatic and so noticeable and perhaps because we have assumed that what happens during these years provides a foundation for one’s life to come.

Rapid Physical Changes

As mentioned in the previous chapter, the average birth weight for babies is around 3.5 kg (7.5 lb), although between 2.5 kg (5.5 lb) and 4.5 kg (10 lb) is considered normal. Newborns often lose around 230 g (8 oz) in the first 4 to 5 days after birth but regain it by about 10 to 12 days of age. In the first month, the typical newborn gains about 20 g (0.7 oz) a day, or about 110 g (4 oz) to 230 g (8 oz) a week.

The average length of full-term babies at birth is 51 cm. (20 in), although the normal range is 46 cm (18 in.) to 56 cm (22 in.). In the first month, babies typically grow 4 cm (1.5 in.) to 5 cm (2 in.). (Government of Alberta, 2021).

Two hormones are very important to this growth process. The first is Human Growth Hormone (HGH) which influences all growth except that in the Central Nervous System (CNS). The hormone influencing growth in the CNS is called Thyroid Stimulating Hormone. Together these hormones influence growth in early childhood

Proportions of the Body

The increased weight that takes place in the first several years of life results in a change in body proportions. The head initially makes up about 50 percent of our entire length when we are developing in the womb. At birth, the head makes up about 25 percent of our length (think about how much of your length would be head if the proportions were still the same!). By age 25 it comprises about 20 percent our length. Imagine now how difficult it must be to raise one’s head during the first year of life! And indeed, if you have ever seen a 2 to 4 month old infant lying on the stomach trying to raise the head, you know how much of a challenge this is. The comparison in this graphic was originally introduced in the last chapter.

Figure 4.1: (Image: © TheVisualMD/Science Source. )

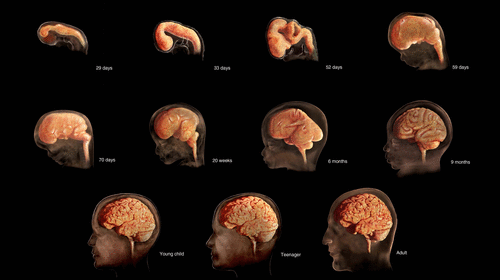

Some of the most dramatic physical changes that occur during this period happen in the brain. At birth, the brain is already about 25 percent its adult weight and this is not true for any other part of the body. By age 2, it is at 75 percent its adult weight, at 95 percent by age 6 and at 100 percent by age 7 years.

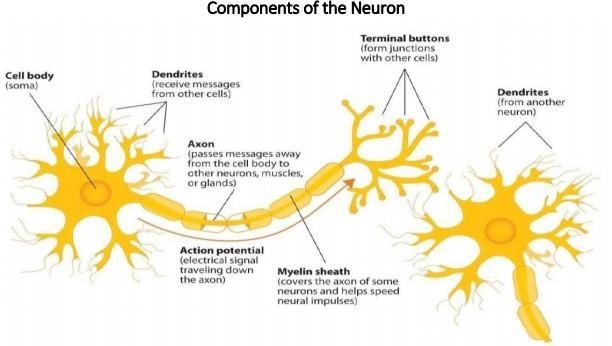

The basic building blocks of the brain are specialized nerve cells called neurons. These neurons proliferate before birth. In fact, a fetus’ brain produces roughly twice as many neurons as it will eventually need — a safety margin that gives newborns the best possible chance of coming into the world with healthy brains. Most of the excess neurons are shed in utero, leaving approximately 100 billion of these brain nerve cells left present at birth. As a child matures, the number of neurons they have will remain relatively stable, but each brain nerve cell will grow, becoming bigger and heavier. This happens with both regular growth, and as the dendrites connect the neurons together (Graham & Forstadt, 2011).

Figure 4.2: Components of the Neuron

There is a proliferation of these dendrites during the first two years so that by age 2, a single neuron might have thousands of dendrites. After this dramatic increase, the neural pathways that are not used will be eliminated thereby making those that are used much stronger (Lumen Learning, n.d.). Because of this proliferation of dendrites, by age two a single neuron might have thousands of dendrites.

Synaptogenesis, or the formation of connections between neurons, continues from the prenatal period forming thousands of new connections during infancy and toddlerhood. This period of rapid neural growth is referred to as Synaptic Blooming (Lumen Learning, n.d.). This activity is occurring primarily in the cortex or the thin outer covering of the brain involved in voluntary activity and thinking. The prefrontal cortex that is located behind our forehead continues to grow and mature throughout childhood and experiences an additional growth spurt during adolescence. It is the last part of the brain to mature and will eventually comprise 85 percent of the brain’s weight. Experience will shape which of these connections are maintained and which of these are lost. Ultimately, about 40 percent of these connections will be lost (Webb, Monk, and Nelson, 2001, as cited in Paris, Ricardo, Raymond, & Johnson, 2021). As the prefrontal cortex matures, the child is increasingly able to regulate or control emotions, to plan activity, strategize, and have better judgment. Of course, this is not fully accomplished in infancy and toddlerhood but continues throughout childhood and adolescence.

Another major change occurring in the central nervous system is the development of myelin, a coating of fatty tissues around the axon of the neuron. Myelin helps insulate the nerve cell and speed the rate of transmission of impulses from one cell to another. This enhances the building of neural pathways and improves coordination and control of movement and thought processes. The development of myelin continues into adolescence but is most dramatic during the first several years of life (Lally & Valentine-French, 2019).

Reflexes

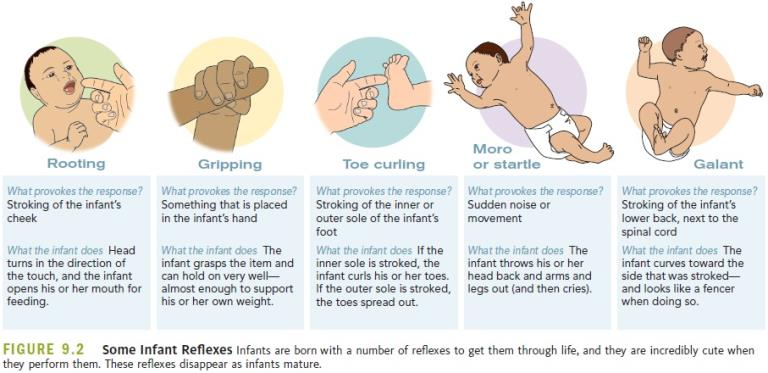

Infants are equipped with a number of reflexes which are involuntary movements in response to stimulation. These include the sucking reflex (infants suck on objects that touch their lips automatically), the rooting reflex (which involves turning toward any object that touches the cheek), the palmar grasp (the infant will tightly grasp any object placed in its palm), and the dancing reflex (evident when the infant is held in a standing position and moves its feet up and down alternately as if dancing). These movements occur automatically and are signals that the infant is functioning well neurologically. Within the first several weeks of life these reflexes are replaced with voluntary movements or motor skills.

Figure 4.3: (Image: https://www.sutori.com/en/item/untitled-4f52-ab3f)

As discussed earlier, the Continuum of Development is a guide, produced by the Ontario Ministry of Education, that identifies sequences of development across five domains. A domain is a broad area or dimension of development. One of the five domains outlined in the Continuum of Development is Physical. Physical skills learned by an infant are: Gross Motor Skills, Fine Motor Skills, Senses and Sensory Motor Integration (Ontario Ministry of Education, 2014).

Gross Motor Skills

Gross motor skills are voluntary movements which involve the use and coordination of large muscle groups and are typically large movements of the arms, legs, head, and torso. They are also referred to as large motor skills. These skills begin to develop first. Examples include moving to bring the chin up when lying on the stomach, moving the chest up, rocking back and forth on hands and knees, and then locomotion. It also includes exploring an object with ones feet as many babies do as early as 8 weeks of age if seated in a carrier or other device that frees the hips. This may be easier than reaching for an object with the hands, which requires much more practice (Berk, 2007, as cited in Paris, Ricardo, Raymond, & Johnson, 2021). Sometimes an infant will try to move toward an object while crawling and surprisingly move backward because of the greater amount of strength in the arms than in the legs! This also tends to lead infants to pull up on furniture, usually with the goal of reaching a desired object. Usually, this will also lead to taking steps and eventually walking (Leon, n.d.).

When considering gross motor movements, the Continuum of Development focuses on the following:

- Reaching and holding: reaching towards objects as well as reaching and holding with palmar grasp;

- Releasing objects: dropping and throwing objects;

- Holding Head up: lifting one’s head while held on a shoulder;

- Lifting upper body: lifting one’s upper body while lying on the floor;

- Rolling: rolling from side to back and rolling from back to side;

- Sitting: sitting without support;

- Crawling: crawling on hands and/or knees;

- Pulling self to stand: using objects/people to pull self to standing position;

- Cruising: walking while holding onto objects;

- Walking: moving on one’s feet, unassisted, with a wide gait;

- Strength: increasing strength in gross motor skills

- Coordination: using different body parts at the same time, smoothly and efficiently. (Ontario Ministry of Education, 2014)

Fine Motor Skills

More exact movements of the feet, toes, hands, and fingers are referred to as fine motor skills (or small motor skills). When considering fine motor skills, the Continuum of Development focuses on:

- Palmar grasp: holding objects with whole palm;

- Coordination: holding and transferring object from hand to hand and manipulating small objects with improved coordination;

- Pincer grasp: using forefinger and thumb to lift and hold small objects;

- Holding and using tools: making marks with first crayon, or using utensil to feed. (Ontario Ministry of Education, 2014)

the senses

The brain interprets the information that the senses collect from the environment. When considering the senses, the Continuum of Development focuses on the following:

- Visual: The Continuum of Development focuses on the following four elements of visual sense development:

- Face Perception: showing a preference for simple face-like patterns by looking longer, responding to emotional expressions with facial expressions and gestures, and/or turning and looking at familiar faces;

- Pattern Perception: showing a preference for patterns with large elements, showing a preference for increasingly complex patterns, visually exploring borders and/or visually exploring entire object;

- Visual Exploration: tracking moving objects with eyes, and/or looking and searching visually;

- Visual Discrimination: scanning objects and identifying them by sight. (Ontario Ministry of Education, 2014)

It is important to share that the womb is a dark environment void of visual stimulation. Consequently, vision is the most poorly developed sense at birth and time is needed to build those neural pathways between the eye and the brain. Newborns typically cannot see further than 8 to 16 inches away from their faces (which is about the distance from the newborn’s face to the mother/caregiver when an infant is breastfeeding/bottle-feeding). Their visual acuity is about 20/400, which means that an infant can see something at 20 feet that an adult with normal vision could see at 400 feet. Thus, the world probably looks blurry to young infants. Because of their poor visual acuity, they look longer at checkerboards with fewer large squares than with many small squares. Infants’ thresholds for seeing a visual pattern are higher than that of an adults. Thus, toys for infants are sometimes manufactured with black and white patterns rather than pastel colours because the higher contrast between black and white makes the pattern more visible to the immature visual system. By about 6 months, infants’ visual acuity improves and approximates adult 20/25 acuity.

When viewing a person’s face, newborns do not look at the eyes the way adults do; rather, they tend to look at the chin – a less detailed part of the face. However, by 2 or 3 months, they will seek more detail when exploring an object visually and begin showing preferences for unusual images over familiar ones, for patterns over solids, for faces over patterns, and for three- dimensional objects over flat images. Newborns have difficulty distinguishing between colours, but within a few months, they are able to discriminate between colours as well as adults do. Sensitivity to binocular depth cues, which require inputs from both eyes, is evident by about 3 months and continues to develop during the first 6 months. By 6 months, the infant can perceive depth perception in pictures as well (Sen, Yonas, & Knill, 2001, as cited in Paris, Ricardo, Raymond, & Johnson, 2021). Infants who have experience crawling and exploring will pay greater attention to visual cues of depth and modify their actions accordingly (Berk, 2007, as cited in Paris, Ricardo, Raymond, & Johnson, 2021).

- Auditory: The Continuum of Development focuses on the following two elements of auditory sense development.

- Auditory Exploration: making sounds by shaking and banging objects; turning to source of a sound, responding to familiar sounds with gestures and actions, and/or responding by turning towards a sound even when more than one sound is present;

- Auditory Discrimination: touching, rubbing, squeezing materials. (Ontario Ministry of Education, 2014)

The infant’s sense of hearing is very keen at birth, and the ability to hear is evident as soon as the 7th month of prenatal development. In fact, an infant can distinguish between very similar sounds as early as one month after birth and can distinguish between a familiar and unfamiliar voice even earlier. Infants are especially sensitive to the frequencies of sounds in human speech and prefer the exaggeration of infant-directed speech, which will be discussed later. Additionally, infants are innately ready to respond to the sounds of any language, but some of this ability will be lost by 7 or 8 months as the infant becomes familiar with the sounds of a particular language and less sensitive to sounds that are part of an unfamiliar language.

Newborns also prefer their mother’s voices over another female when speaking the same material (DeCasper & Fifer, 1980, as cited in Paris, Ricardo, Raymond, & Johnson, 2021). Additionally, they will register in utero specific information heard from their mother’s voice.

- Touch: As discussed above, many areas of the infant’s body respond reflectively when touched. Touching an infant’s cheek, mouth, hand and foot produces reflexive movements, signifying that the infant feels those touches. Immediately after birth, a newborn is sensitive to touch and temperature, and is also highly sensitive to pain, responding with crying and cardiovascular responses (Balaban & Reisenauer, 2013, as cited in Paris, Ricardo, Raymond, & Johnson, 2021). Newborns who are circumcised, which is the surgical removal of the foreskin of the penis, without anesthesia experience pain as demonstrated by increased blood pressure, increased heart rate, decreased oxygen in the blood, and a surge of stress hormones (United States National Library of Medicine, 2016, as cited in Paris, Ricardo, Raymond, & Johnson, 2021).

- Olfactory: Infants have a keen sense of smell. Studies have shown that they prefer the smell of their mothers. An infant only 6 days old is significantly more likely to turn toward its own mother’s breast pad than to the breast pad of another baby’s mother (Porter, Makin, Davis, & Christensen, 1992, as cited in Paris, Ricardo, Raymond, & Johnson, 2021), and within hours of birth, an infant also shows a preference for the face of its own mother (Bushnell, 2001; Bushnell, Sai, & Mullin, 1989, as cited in Paris, Ricardo, Raymond, & Johnson, 2021).

- Taste: Infants have a highly developed sense of taste. They can distinguish between sour, bitter, sweet, and salty flavours and show a preference for sweet flavours (Rostenstein & Oster, 1997, as cited in Paris, Ricardo, Raymond, & Johnson, 2021). Infants seem to have a preference for sweet tastes and responding by smiling, sucking and licking their lips (Kaijura, Cowart and Beauchamp, 1992, as cited in Paris, Ricardo, Raymond, & Johnson, 2021). Also, it has been found that they will nurse more after their mother has consumed a sweet tasting substance, such as vanilla (Mennella & Beauchamp, 1996, as cited in Paris, Ricardo, Raymond, & Johnson, 2021).

Sensory Motor Integration

According to Brown (n.d.), sensory motor integration refers to a relationship between the sensory system (nerves) and the motor system (muscles). Also, it refers to the process by which these two systems (sensory and motor) communicate and coordinate with each other. In the process of developing sensory motor integration, a child first learns to move and then they learn through movement. Learning to move involves continuous development in a child’s ability to use the body with more and more skillful purposeful movement. Then, through this movement, the child learns more about themselves as they explores their environment. The process has three parts: (1) a sense organ receives a stimulus, (2) the nerves carry the information to the brain where the information is interpreted. (3) The brain then determines what response to make and transmits its instructions to the appropriate group of muscle fibres that carry out the response.

These two systems work together as a team, and if the sending nerve impulses are problematic, the brain will not receive the message, and if the breakdown is in the motor nerves, the muscles will not get a clear message and will not be able to give the correct motor response (Brown, n.d.). Interestingly, infants seem to be born with the ability to perceive the world in an intermodal way; that is, through stimulation from more than one sensory modality. For example, infants who sucked on a pacifier with either a smooth or textured surface preferred to look at a corresponding (smooth or textured) visual model of the pacifier. By 4 months, infants can match lip movements with speech sounds and can match other audiovisual events. Although sensory development emphasizes the afferent processes used to take in information from the environment, these sensory processes can be affected by the infant’s developing motor abilities. Reaching, crawling, and other actions allow the infant to see, touch, and organize his or her experiences in new ways (Brown, n.d).

Nutrition

Feeding Infants

According to the Canadian Pediatric Society (2020), for the first six months of life, breastfed infants will get what they need from their mother’s milk. Breast milk has the right amount and quality of nutrients to suit the baby’s first food needs. Breast milk also contains antibodies and other immune factors that help infants prevent and fight off illness. There are many reasons that mothers struggle to breastfeed or should not breastfeed, including: low milk supply, previous breast surgeries, illicit drug use, medications, infectious disease, and inverted nipples. Other mothers choose not to breastfeed. Some reasons for this include: lack of personal comfort with nursing, the time commitment of nursing, inadequate or unhealthy diet, and wanting more convenience and flexibility with who and when an infant can be fed. If breastfeeding is not an option, it is recommended that families seek out a store-bought iron-fortified infant formula for the first 9 to 12 months. This formula should be cow milk-based unless the infant cannot consume dairy-based products for medical, cultural or religious reasons. It should be noted that breastfed and bottle-fed infants adjust equally well emotionally (Ferguson & Woodward, 1999, as cited in Paris, Ricardo, Raymond, & Johnson, 2021).

Introducing Infants to Solid Food

According to the Canadian Pediatric Society (2020), while breast feeding and/or bottle feeding must still occur, at about 6 months of age most babies are ready to be introduced to solid foods. Typically, infants are ready for this milestone when they:

- Can sit up without support, lean forward, and have good control of their neck muscles.

- Have the ability to pick up food and try to put it in their mouth.

- Can hold food in their mouth without pushing it out with their tongue right away.

- Show interest in food when others are eating.

- Open their mouth when they see food coming their way.

- Can let you know they don’t want food by leaning back or turning their head away.

| Age | Physical milestones | Social milestones |

| Birth to 4 months |

|

|

| 4 to 6 months |

|

|

| 6 to 9 months |

|

|

| 9 to 12 months |

|

|

| 12 to 18 months |

|

|

| 18 to 24 months |

|

|

Table 4.1: Developmental milestones related to feeding. (Canadian Pediatric Society, 2020)

How Should Foods Be Introduced?

The Canadian Paediatric Society (2020) shares that there are many ways to introduce solid food to ready infants. The first foods usually vary from culture to culture and from family to family. Healthy foods that the family is already eating are usually the best choice for the infant. It is recommended that families begin by introducing foods that contain iron, which babies need for many different aspects of their development. Meat, poultry, cooked whole egg, fish, tofu, and well-cooked legumes (beans, peas, lentils) are all good sources of iron. These foods are served to an infant in pureed form. Pureed food can be purchased commercially or can be made from home. If they are purchased, it is important to read the nutritional labels to ensure that there is no added salt or sugar. Infants should be introduced to foods with variety of textures (such as lumpy, tender-cooked and finely minced, puréed, mashed or ground), as well as soft finger foods. Staggering the introduction of new foods is always recommended. Infants should be allowed to try one food at a time at first and there should be 3 to 5 days before another food is introduced. This helps caregivers identify if the child has any reactions with that food, such as food allergies.

An allergy happens when a person’s immune system treats a substance (allergen) like an inappropriate invader. The body will try to protect itself by releasing a chemical into the body called histamine. This chemical is what causes the symptoms that are unpleasant or even dangerous. The reaction can start very suddenly, even after being exposed to a small amount of the allergen. An allergic reaction can affect many different body parts. Symptoms can include: itchy mouth and throat when eating certain foods, hives (raised red, itchy bumps on the skin), stomach trouble (diarrhea, cramps, nausea, vomiting), swelling of the face or tongue, or trouble breathing. Any food can trigger an allergic reaction, but the most common are: peanuts, tree nuts, eggs, shellfish, fish, milk, soy, wheat (Canadian Paediatric Society, 2021). Sometimes, allergic reactions can be very serious, even life-threatening. In rare cases, a child may have a rapid and severe reaction to an allergen. This is called anaphylactic shock or anaphylaxis. It can happen within minutes or up to 2 hours after being exposed to an allergen. Symptoms of anaphylaxis include: difficulty breathing, swelling of the face, throat, lips, and tongue (in cases of food allergies), rapid drop in blood pressure, dizziness, unconsciousness, hives, tightness of the throat, hoarse voice, lightheadedness.

It isn’t recommended that families wait longer to introduce common allergenic foods to their infants as there is no evidence that avoiding certain foods will prevent allergies in children. If a reaction is identified, families will typically reach out to their paediatrician for support and recommendations. Children can outgrow some types of food allergies, especially if the allergy started before age 3. Allergies to milk, for example, will usually go away. However, some allergies, like those to nuts and fish, may not go away.

Some children have reactions to foods that are not as severe as discussed above. A food intolerance is different from an allergy. It is not caused by an immune reaction. Food intolerance will cause discomfort, but it’s not dangerous. Symptoms that may be experienced include bloating, loose stools, gas or other symptoms after eating a specific food. Even though this reaction is not dangerous, families often make the choice to avoid those foods in the future and this must be respected in the early learning environment.

| Iron-rich foods | Pureed, minced, diced or cooked meat, fish, chicken, tofu, mashed beans, peas or lentils, eggs, iron-fortified infant cereal. |

| After 6 months | |

| Grain products | Iron-fortified infant cereal, small pieces of dry toasts, small plain cereals, whole grain bread pieces, rice and small-sized pasta. |

| Vegetables | Pureed, mashed, lumpy or pieces of soft cooked vegetables. |

| Fruit | Pureed, mashed or lumpy soft fruit. Pieces of very ripe soft fresh fruit, peeled, seeded and diced or canned fruit (not packed with syrup). |

| Milk products | Dairy foods like full-fat-yogurt, full-fat grated or cubed pasteurized cheeses, cottage cheese. |

| 9 to 12 months | |

| Milk | Whole cow’s milk (3.25%) can be introduced if breastmilk is no longer available, between 9-12 months.

After 12 months of age, your baby should not take more than 25 ounces (750 mL) of milk per day. Otherwise, they will fill up and won’t want to eat solid foods. Too much milk can also lead to iron deficiency anemia. |

Table 4.2: First foods – Around 6 months (Canadian Paediatric Society, 2020)

| Meal Times | 6 to 9 months |

| Early morning | Breastmilk or infant formula

Vitamin D drops for breastfed babies |

| Breakfast | Breastmilk or infant formula, iron fortified infant cereal mixed with breastmilk, formula or water

Mashed fruit like banana or pears mixed with full fat plain yogurt |

| Snack | Breastmilk or infant formula |

| Lunch | Breastmilk or infant formula, iron fortified infant cereal mixed with breastmilk, formula or water

Mashed vegetables (sweet potato, squash or carrots) Cooked ground beef, chicken, pork or fish Well-cooked chopped egg or silken (soft) tofu |

| Snack | Breastmilk or infant formula |

| Dinner | Breastmilk or infant formula, iron fortified infant cereal mixed with breastmilk, formula or water

Cooked vegetables (carrots, pieces of soft-cooked green beans or broccoli) Cooked, minced chicken or turkey or canned or cooked legumes (beans, lentils, or peas) Fruits like unsweetened applesauce, mashed banana or pureed melon mixed with full fat plain yogurt |

| Bedtime snack | Breastmilk or infant formula |

Table 4.3: Sample Meals for Baby: 6 to 9 months old (Dieticians of Canada, 2020)

| Meal times | 9 to 12 months |

| Early morning | Breastmilk, infant formula or 3.25% homogenized whole cow’s milk

Vitamin D drops |

| Breakfast | Iron fortified infant cereal mixed with breastmilk, formula, 3.25% homogenized whole cow’s milk or water

Full-fat plain yogurt, unsalted cottage cheese or grated cheese Cooked chopped egg Soft fruit (chopped banana, avocado, peach, seedless watermelon, cantaloupe, papaya, plum or kiwi) Breastmilk, formula or 3.25% homogenized whole cow’s milk |

| Morning Snack | Strips of whole-grain bread or roti

Grated apple or chopped strawberries Breastmilk, formula or 3.25% homogenized whole cow’s milk |

| Lunch | Infant cereal mixed with breastmilk, formula, 3.25% homogenized whole cow’s milk or water

Minced or chopped soft-cooked meat (lamb, pork, veal or beef) Cooked whole wheat pasta, rice or pita bread Cubed avocado or peeled and chopped cucumber Breastmilk, formula or 3.25% homogenized whole cow’s milk |

| Afternoon Snack | Cheese cubes (full fat mozzarella, Swiss or cheddar) with pieces of unsalted whole grain crackers or toast

Breastmilk, formula or 3.25% homogenized whole cow’s milk |

| Dinner | Infant cereal mixed with breastmilk, formula, 3.25% homogenized whole cow’s milk or water

Diced or cut up cooked or canned flaked fish or pieces of firm tofu or chicken Cut up vegetables (soft-cooked green beans, okra, cauliflower, broccoli or carrots) Soft fruit (chopped banana, ripe peach or mango or quartered grapes) Breastmilk, formula or 3.25% homogenized whole cow’s milk |

| Bedtime Snack | Small pieces of whole grain toast, bread, crackers or unsweetened dry O-shaped cereal

Breastmilk, formula or 3.25% homogenized whole cow’s milk |

Table 4.4: Sample Meals for Baby: 9 to 12 months old (Dieticians of Canada, 2020)

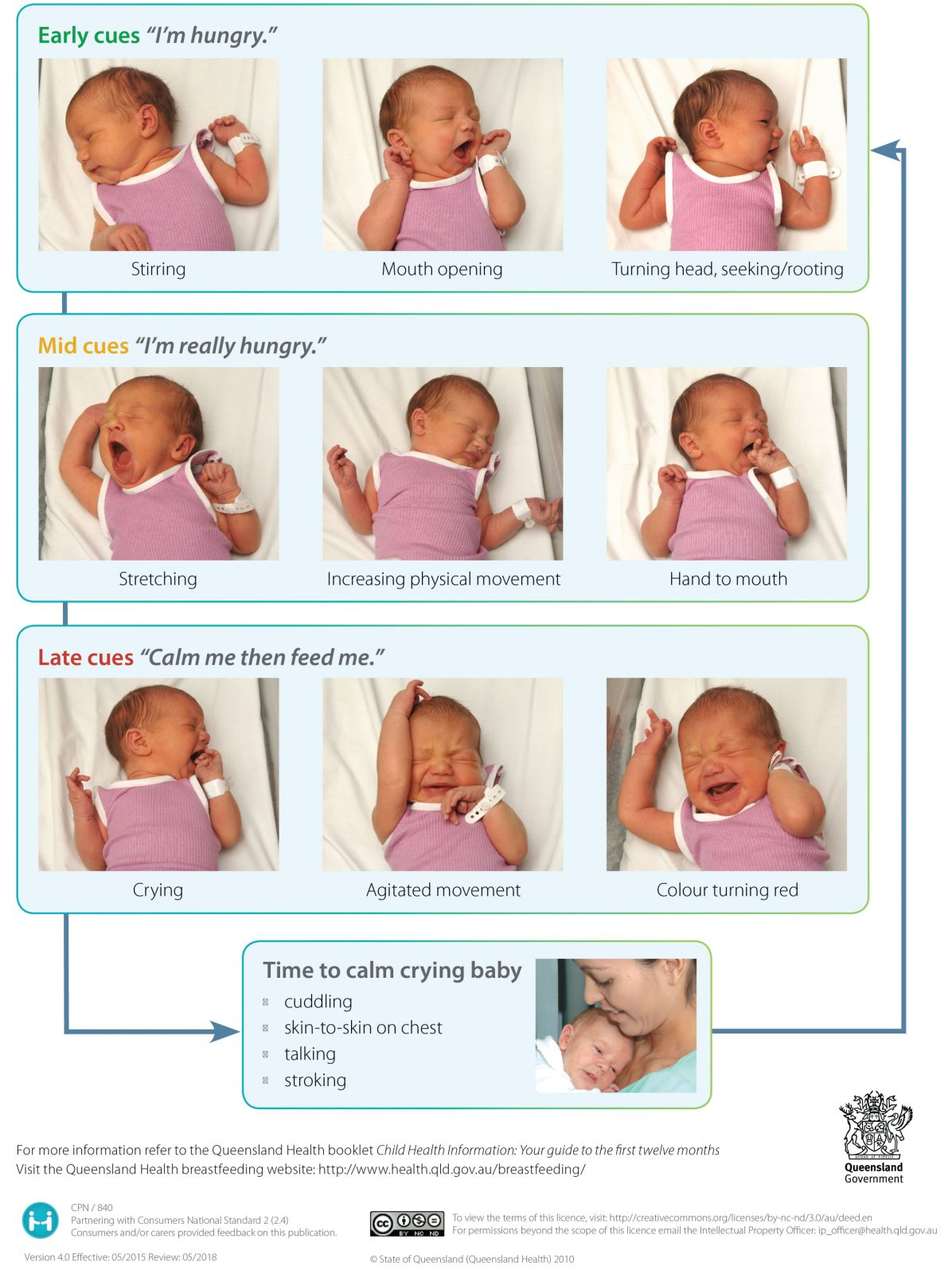

Infants attending licensed child care in Ontario will have an individualized feeding plan designed with their primary educator. Feeding can include breast/formula bottles and/or solid foods and can be done on schedule (every 3-4 hours) and on demand (as the infant shows hunger cues). Typically, one educator is assigned to the feeding of each infant. The educator is not only responsible for the actual feeding of the child, as per the plan, but also for documenting what was eaten. This documentation is communicated with the family, either through a communication book or a software application like Seesaw, HiMama or Storypark, etc.

According to Leduc (2015), understanding hunger cues in infants is very important – rapid eye movement, waking, stretching, hand-to mouth activity, sucking, licking… These are all the ways that infants can communicate what they need to you.

Figure 4.4: (Queensland Government, 2010)

When feeding infants, it is important to make feeding time calm. This time is a good opportunity for the building of rapport – talk, sing, be in the moment; let the child regulate the milk intake – do not coax/force child to drink; keep the nipple of the bottle full of milk/formula to reduce the amount of swallowing too much air (Leduc, 2015).

According to the Dieticians of Canada (2020), it is recommended that children one years old and up follow the Canada Food Guide. Children need a balanced diet with food from all 3 food groups—vegetables and fruit, whole grain products, and protein foods. Children need 3 meals a day and 2 to 3 snacks (morning, afternoon and possibly before bed). Healthy snacks are just as important as the food served at meals.

| Sample Menu 1 | |

| Breakfast | Mini Oatmeal pancakes with sliced bananas and nut butter

Breastmilk or milk in a cup |

| Morning Snack | Ripe melon pieces

Plain, vanilla or fruit yogurt Water |

| Lunch | Meatballs (cut into small pieces)

Plain macaroni or penne pasta Cooked sweet potato Breastmilk or milk in a cup |

| Afternoon Snack | 100% whole wheat unsalted crackers

Cheese cubes Water |

| Dinner | Baked risotto with salmon

Carrots and parsnips Breastmilk or water |

| Bedtime Snack | Fruity Tutti Muffins with applesauce

Breastmilk or milk in a cup |

Table 4.5: Sample Meals for Feeding Toddlers (1 to 3 years old) (Dieticians of Canada, 2020)

Remember as the educator, it is your job to:

- Set regular meal and snack times. Share mealtimes and eat with the children.

- Offer a balance and variety of foods from all three food groups at mealtimes.

- Offer food in ways they can manage easily. For example: cut into pieces, or mash food to prevent choking in younger children.

- Help children learn to use a spoon or cup so they can eat independently.

- Include the child in age-appropriate food preparation and table setting.

- Avoid using dessert as a bribe. Serve healthy dessert choices, such as a fruit cup or yogurt.

- Show children how you read labels to help you choose foods on the menu, as applicable.

- Act as a role model by making healthy food choices while working with the children.

But it is the child’s job to:

- Choose what to eat from the foods you provide at meal and snack time (and sometimes that may mean not eating at all).

- Eat as much or as little as he/she wants. (Leduc, 2015)

Child Malnutrition

There can be serious effects in the physical growth and development of children when there are deficiencies in their nutrition.

Failure to thrive is a term used to describe a child who seems to be gaining weight or height more slowly than other children of the same age and gender (SickKids, 2009). There are many reasons why a baby might be small for their age; they do not always mean failure to thrive. According to the National Institute of Health (as cited by SickKids, 2009), to be identified as an infant with failure to thrive, the child’s weight must be less than the third percentile on a standard growth chart, or 20% below the ideal weight for length or a fall-off from a previously established growth curve. There are a variety of causes for failure to thrive including maternal stress, diluted formula, feeding difficulties or specific health conditions. Infants who have untreated failure to thrive are at risk of slow development of physical skills, such as rolling over, standing, and walking (SickKids, 2009).

Health

Infants depend on the adults that care for them to promote and protect their health. The following section addresses common physical conditions that can affect infants, the danger of shaking babies, and the importance of immunizations.

Common Physical Conditions and Issues during Infancy

Some physical conditions and issues are very common during infancy. Many are normal, and the infant’s caregivers can deal with them if they occur. Mostly, it is a matter of the caregivers learning about what is normal for their infant and getting comfortable with the new routine in the household. New parents and caregivers often have questions about the following:

Bowel Movements

Infants’ bowel movements go through many changes in colour and consistency, even within the first few days after birth. While the colour, consistency, and frequency of stool will vary, hard or dry stools may indicate dehydration and increased frequency of watery stools may indicate diarrhea.

Colic

Many infants are fussy in the evenings, but if the crying does not stop and gets worse throughout the day or night, it may be caused by colic. According to SickKids (2009), colic is a term used when a baby cries frequently and intensely and is difficult or impossible to soothe. There is disagreement among experts about a formal definition for colic, or if the term colic should even be used. Colic is sometimes diagnosed by the “rule of three”: crying about three hours per day, at least three times per week, for at least three weeks straight. The excessive crying typically begins in the second week of life and continues toward the end of the second month. After that, the colicky behaviour tapers off, usually ending by three or four months of age. Some babies with colic may appear as if they are in pain. They may tend to stretch out their arms and legs, stiffen, and then draw in their arms and legs tightly to their bodies. Their stomachs may be swollen and tight. They may cry inconsolably or scream, extend or pull up their legs, and pass gas. Their stomachs may be enlarged. The crying spells can occur anytime, although they often get worse in the early evening.

It’s normal for healthy babies to cry and some babies cry much more than others. And they cannot always be consoled and caregivers can feel pushed to the limit. When caregivers lose control and shake a baby it can have devastating effects.

Shaken Baby Syndrome (SBS) is a severe form of physical child abuse. SBS may be caused from vigorously shaking an infant by the shoulders, arms, or legs. The “whiplash” effect can cause intracranial (within the brain) or intraocular (within the eyes) bleeding. Often there is no obvious external head trauma. Still, children with SBS may display some outward signs:

- Change in sleeping pattern or inability to be awakened

- Confused, restless, or agitated state

- Convulsions or seizures Loss of energy or motivation

- Slurred speech

- Uncontrollable crying

- Inability to be consoled

- Inability to nurse or eat

SBS can result in death, paralysis, developmental delays, severe motor dysfunction, spasticity, blindness, and/or seizures.

Who’s at Risk?

Small children are especially vulnerable to this type of abuse. Their heads are large in comparison to their bodies, and their neck muscles are weak. Children under one year of age are at highest risk, but SBS has been reported in children up to five years of age.

Can It Be Prevented?

SBS is completely preventable. However, it is not known whether educational efforts will effectively prevent this type of abuse. Home visitation programs are shown to prevent child abuse in general. Home visits bring community resources to families in their homes. Health professionals provide information, healthcare, psychological support, and other services that can help people to be more effective parents and care-givers.

The Bottom Line

Shaking a baby can cause death or permanent brain damage. It can result in life-long disability. Healthy strategies for dealing with a crying baby include:

- Finding the reason for the crying

- Checking for signs of illness or discomfort, such as diaper rash, teething, tight clothing; feeding or burping;

- Soothing the baby by rubbing its back; gently rocking; offering a pacifier; singing or talking;

- Taking a walk using a stroller or a drive in a properly-secured car seat; or calling the doctor if sickness is suspected

All babies cry. Caregivers often feel overwhelmed by a crying baby. Calling a friend, relative, or neighbour for support or assistance lets the caregiver take a break from the situation. If immediate support is not available, the caregiver could place the baby in a crib (making sure the baby is safe), close the door, and check on the baby every five minutes (Safe to Sleep, n.d., as cited in Paris, Ricardo, Raymond, & Johnson, 2021).

Diaper Rash

A rash on the skin covered by a diaper is quite common. It is usually caused by irritation of the skin from being in contact with stool and urine. It can get worse during bouts of diarrhea. Diaper rash usually can be prevented by frequent diaper changes.

Spitting Up/Vomiting

Spitting up is a common occurrence for young infants and is usually not a sign of a more serious problem. But if an infant is not gaining weight or shows other signs of illness, a health care provider should be consulted.

Teething

Babies are born with a set of 20 teeth hidden beneath the gums. Teething is the process of these teeth working their way through the gums. The first teeth normally appear between six and ten months of age, with the rest following over the next two to three years (Ontario Early Years, 2002). As teeth break through the gums, some infants become fussy, and irritable; lose their appetite; or drool more than usual. Teething can cause minor discomfort. Infants may:

- drool

- be more cranky and irritable;

- have red cheeks and red, swollen gums

- show a need to chew on things

While over-the-counter gels for teething should not be used unless advised by a doctor, you can help a infant/child cope safely with teething by:

- Directly massaging an irritated, swollen gum with your finger for a couple of minutes.

- Massaging the gum with a clean, wet cloth that has been chilled in the refrigerator also works well.

- Providing infants/toddlers with a teething ring, wet cloth that has been chilled or chilled foods like banana (hard foods like carrots could cause choking). Babies massage their own gums by chewing on hard, smooth objects like these.

If these suggestions don’t seem to help, an infant’s dose of acetaminophen (over-the counter pain reliever) can be given for one day (Ontario Early Years, 2002).

Urination

Infants urinate as often as every 1 to 3 hours or as infrequently as every 4 to 6 hours. In case of sickness or if the weather is very hot, urine output might drop by half and still be normal. If an infant shows any signs of distress while urinating or if any blood is found in a wet diaper medical care should be sought.

Jaundice

Jaundice can cause an infant’s skin, eyes, and mouth to turn a yellowish colour. The yellow colour is caused by a buildup of bilirubin, a substance that is produced in the body during the normal process of breaking down old red blood cells and forming new ones. Normally the liver removes bilirubin from the body. But, for many infants, in the first few days after birth, the liver is not yet working at its full power. As a result, the level of bilirubin in the blood gets too high, causing the infant’s colour to become slightly yellow—this is jaundice. Although jaundice is common and usually not serious, in some cases, high levels of bilirubin could cause brain injury. All infants with jaundice need to be seen by a health care provider. Many infants need no treatment. Their livers start to catch up quickly and begin to remove bilirubin normally, usually within a few days after birth. For some infants, health care providers prescribe phototherapy—a treatment using a special lamp—to help break down the bilirubin in their bodies.

Figure 4.5: An infant receiving treatment for jaundice. (Image by Andres and Antoinette Ricardo used with permission)

Protecting Health through Immunization

One way we can protect a child’s health (and those around them) is through immunization. The vaccines (given through injection) may hurt a little…but the diseases they can prevent can hurt a lot more! Immunization shots, or vaccinations, are essential. They protect against things like measles, mumps, rubella, hepatitis B, polio, diphtheria, tetanus and pertussis (whooping cough). Immunizations are important for adults as well as for children. Here’s why.

The immune system helps the human body fight germs and bacteria by producing substances to combat them. Once it does, the immune system “remembers” the germ and can fight it again. Vaccines contain germs and bacteria that have been killed or weakened. When given to a healthy person, the vaccine triggers the immune system to respond and thus build immunity.

Before vaccines, people became immune only by actually getting a disease and surviving it. Immunizations are an easier and less risky way to become immune.

Vaccines are the best defense we have against serious, preventable, and sometimes deadly contagious diseases. Vaccines are some of the safest medical products available, but like any other medical product, there may be risks. Accurate information about the value of vaccines as well as their possible side effects helps people to make informed decisions about vaccination.

Figure 4.6: A nurse giving an infant vaccinations. (Image by Maria Immaculata Hospital is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0)

Side Effects:

Vaccines, like all medical products, may cause side effects in some people. Most of these side effects are minor, such as redness or swelling at the injection site or low-grade fever and go away within a few days. Serious side effects after vaccination, such as severe allergic reaction, are very rare.

When to vaccinate?

On-time vaccination throughout childhood is essential because it helps provide immunity before children are exposed to potentially life-threatening diseases. Vaccines are tested to ensure that they are safe and effective for children to receive at the recommended ages. Fully vaccinated children in Ontario are protected against sixteen potentially harmful diseases.

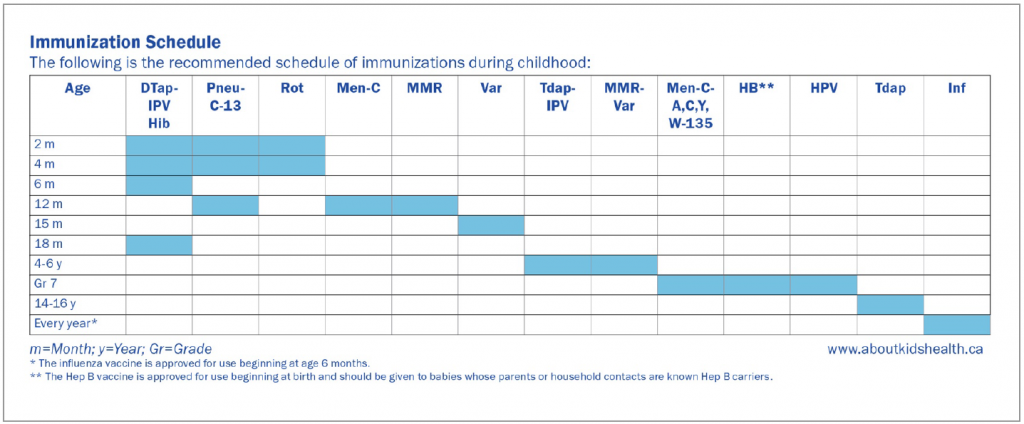

The following chart is the recommended schedule of immunizations during childhood for the province of Ontario as of December 2016. For the most current recommendations according to the National Advisory Committee on Immunization and for each province and territory go to the Government of Canada website.

Figure 4.7: (Government of Canada, 2021)

Descriptions of immunizations

DTap-IPV-Hib: Diphtheria, tetanus, acellular pertussis, inactivated polio virus, haemophilus influenzae type B vaccine

Immunization against diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis (whooping cough) is important, since all of these diseases can be deadly. Pertussis is a serious disease, especially for young babies. Children who get pertussis can have spells of violent coughing. The cough can cause children to stop breathing for brief periods of time. The cough can last for weeks and makes it difficult for children to eat, drink and breathe. The risk of children getting pertussis increases if fewer children are immunized. The polio vaccine protects children from this now rare but crippling disease. Polio can cause nerve damage and can paralyze a person for the rest of their life. The inactivated polio vaccine is now recommended for all polio doses. Haemophilus influenzae is a type of bacteria that causes several life-threatening diseases in young children such as meningitis, epiglottitis, and pneumonia. Before the vaccine was available, a large number of children developed H. influenzae meningitis each year. Some died and others developed learning or developmental problems such as blindness, deafness, or cerebral palsy. Because of the vaccine, H. influenzae type B infection is now uncommon. The Hib vaccine does not protect against pneumonia and meningitis caused by viruses.

Pneu-C-13: Pneumococcal conjugate (13-valent) vaccine

Pneumococcal infections are serious bacterial infections that may cause pneumonia, bloodstream infections, and meningitis. The pneumococcal vaccine protects against the thirteen types of pneumococcal bacteria that cause most of these serious diseases. The vaccine also prevents a small percentage of ear infections caused by pneumococci. Routine use of pneumococcal vaccine is now recommended for babies and toddlers. Some older children with serious illnesses, such as sickle cell anemia, may also benefit from the vaccine.

Rota: Rotavirus oral vaccine

Rotavirus is a condition that causes vomiting and diarrhea. Sometimes the diarrhea is so severe, children need to be hospitalized. It is very contagious and spreads easily between children. Vaccines active against rotavirus became available at the beginning of 2006. The rotavirus vaccine is given by mouth.

Men-C-C: Meningococcal conjugate C vaccine

Meningococcal infections are serious bacterial infections that cause bloodstream infections or meningitis.

MMR: Measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine

This is a three-in-one immunization that protects against measles, mumps and rubella. It is given in infancy and then again at pre-school age.

Var: Varicella (chickenpox) vaccine

This vaccine is 70% to 90% effective in preventing chickenpox. If vaccinated children get chickenpox, they have a much milder form of the disease.

Men-C-ACYW-135: Meningococcal conjugate ACYW-135 vaccine

Students in Grade 7 are eligible to receive a single dose of this vaccine. Students who were eligible in Grade 7 and have not yet received the vaccine are eligible for a single dose of Men-C-ACYW.

HB: Hepatitis B vaccine

Vaccination against hepatitis B prevents this type of hepatitis and the severe liver damage that can occur 20 or 30 years after a person is first infected. A significant number of adults die each year from hepatitis-related liver cancer or cirrhosis. The younger the person is when the infection occurs, the greater the risk of serious problems. Students in Grade 7 are eligible to receive this vaccine.

HPV: Human papillomavirus vaccine

HPV is a virus that can lead to different types of cancers in females and males. Both males and females are eligible to receive this vaccine starting in Grade 7.

Inf: Seasonal influenza vaccine

Influenza is a common respiratory virus in the fall and winter. It can lead to pneumonia and hospitalization, especially in young children and children with underlying medical conditions. All children and youth are encouraged to get the seasonal influenza vaccine.

Other vaccines

Hepatitis A vaccine

The hepatitis A vaccine is recommended for children and teenagers in selected geographic regions, and for certain people at high risk. Talk to your health care provider or local public health unit for more information.

COVID-19

Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) is an infectious disease caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus. It spreads from an infected person’s mouth or nose in small liquid particles when they cough, sneeze, speak, sing or breathe. At the time of the writing of this text, COVID-19 vaccinations are only available in Ontario to children 5 years of age and older (World Health Organization, 2021).

Sleep

A newborn typically sleeps approximately 16.5 hours per 24-hour period. This is usually polyphasic sleep in that the infant is accumulating the 16.5 hours over several sleep periods throughout the day (Salkind, 2005, as cited in Paris, Ricardo, Raymond, & Johnson, 2021). The infant is averaging 15 hours per 24-hour period by one month, and 14 hours by 6 months. By the time children turn two, they are averaging closer to 10 hours per 24 hours. Additionally, the average newborn will spend close to 50% of the sleep time in the Rapid Eye Movement (REM) phase, which decreases to 25% to 30% in childhood (Lally & Valentine-French, 2019).

Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS) is identified when the death of a healthy infant occurs suddenly and unexpectedly, and medical and forensic investigation findings (including an autopsy) are inconclusive. SIDS is rare before one month of age, peaks at 2 to 4 months, and is also rare after one year of age. It is estimated that it takes the life of 1 of every 2,000 live-born babies in Canada. Babies of aboriginal background are at greater risk of SIDS. It is estimated that three babies die of SIDS every week in Canada (Baby’s Breath, 2016). It is difficult to get an accurate statistic on SIDS because of the definition of SIDS and the usage of different terms (ie. undetermined) that may include other causes of death. We do know that SIDS rates varies from place to place and from year to year. SIDS also occurs throughout the world.

We do not know the cause or causes of SIDS. At this time, SIDS is neither predictable nor preventable and the cause or causes of SIDS are not proven. Many researchers think that SIDS is not a single disease but rather is a result of multiple interacting factors. Current advances in medicine indicate that an underlying abnormality due to genetic, biologic or molecular disorders may be responsible for a large proportion of sudden infant deaths. At present genetic and molecular testing are not yet part of routine sudden infant death investigations carried out by the coroners or medical examiners. Restricted access to tissues from SIDs victims and limited funding for research continue to be major obstacles for progress (Baby’s Breath, 2016).

While risk reduction strategies, including safe sleep practices, have helped lower the rate of SIDS in recent years, they cannot alone prevent SIDS. Risk factors are not causes. SIDS can happen to babies with known risk factors, as well as babies who have no known risk factors. It can still occur even when families and caregivers follow all recommended risk reduction strategies. The only way that we will one day be able to prevent SIDS deaths is by finding, understanding and treating the underlying biological causes of SIDS (Baby’s Breath, 2016).

Indigenous Perspective

Native teachings indicate that a child is a gift from the creator and the creation of life is sacred. The following website expands on Sudden Infant Death Syndrome and Indigenous communities. Sudden Infant Death Syndrome and Aboriginals

The following study includes a report on sleeping practices among Inuit Infants. Sleep Practices among Inuit Infants and the Prevention of SIDS

Summary

References

Brown, E. (n.d.). Sensory motor integration. Retrieved from https://www.understanding-learning-disabilities.com/sensory-motor-integration.html

Baby’s Breath. (2016). What every SIDs parent should know. Retrieved from https://www.babysbreathcanada.ca/what-is-sids-sudc-stillbirth/what-every-sids-parent-should-know/

Canadian Pediatric Society. (2021). Food allergy vs. food intolerance: What is the difference and can I prevent them? Retrieved from https://www.caringforkids.cps.ca/handouts/healthy-living/food_allergies_and_intolerances

Canadian Pediatric Society. (2020). Feeding your baby in the first year. Retrieved from https://www.caringforkids.cps.ca/handouts/pregnancy-and-babies/feeding_your_baby_in_the_first_year

Dieticians of Canada. (2020). Sample meal plans for feeding your baby. Retrieved from https://www.unlockfood.ca/en/Articles/Breastfeeding-Infant-feeding/Sample-meal-plans-for-feeding-your-baby.aspx

Graham, J. & Forstadt, L. (2011). Bulletin #4356, Children and brain development: What we know about how children learn. Retrieved from https://extension.umaine.edu/publications/4356e/

Government of Alberta. (2021). Physical growth in newborns. Retrieved from https://myhealth.alberta.ca/Health/Pages/conditions.aspx?hwid=te6295

Government of Canada. (2021). Provincial and territorial routine and catch-up vaccination schedule for infants and children in Canada. Retrieved from https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/provincial-territorial-immunization-information/provincial-territorial-routine-vaccination-programs-infants-children.html

Lally, M. & Valentine-French, S. (2019). Lifespan development: A psychological perspective (2nd ed.). Retrieved from http://dept.clcillinois.edu/psy/LifespanDevelopment.pdf

Leduc, D. (Ed.). (2015). Well beings: A guide to health in child care (3rd ed.). Ottawa, ON: Canadian Paediatric Society.

Leon, A. (n.d.). Children’s development: Prenatal through adolescent development. Retrieved from https://docs.google.com/document/d/1k1xtrXy6j9_NAqZdGv8nBn_I6-lDtEgEFf7skHjvE-Y/edit

Lumen Learning. (n.d.). Physical development. Retrieved from https://courses.lumenlearning.com/lifespandevelopment2/chapter/physical-development/

Ontario Early Years. (2002). Teething: What can I expect. Retrieved from https://www.health.gov.on.ca/english/providers/pub/early/fact_sheets/english/teething_e.pdf

Ontario Ministry of Education. (2014). Excerpts from ELECT. Retrieved from https://countrycasa.ca/images/ExcerptsFromELECT.pdf

Queensland Government ( 2020). Breastfeeding: Signs of hunger. Retrieved from https://www.qld.gov.au/health/children/pregnancy/antenatal-information/breastfeeding-101/signs-of-hunger

SickKids. (2009). Failure to thrive. Retrieved from https://www.aboutkidshealth.ca/Article?contentid=514&language=English

World Health Organization. (2021). Coronavirus disease (COVID-19). Retrieved from https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/advice-for-public