16 Social Development in Middle Childhood

Chapter Objectives

After this chapter, you should be able to:

- Describe the continuum of development of social skills during middle childhood

- Describe social theories of development

- Examine a variety of family structures

- Discuss the effects of divorce on children in middle childhood

- Examine the importance of positive friendships and peer relationships

- Explain aggression, antisocial behaviour, and bullying.

INTRODUCTION

Between the ages of 6 and 12 years, children experience significant changes in their relationships with adults and peers. Let’s examine some of these important social interactions during these years.

Indigenous Perspectives

Between the ages of 9 and 12, First Nation children are learning more and more about their responsibilities within the scope of family and community. This is a crucial time because hormones are starting to be more prominent in their bodies. They are starting to search for what their place is in the community. In the northernmost communities, boys (and some girls) from traditional/cultural families who exercise their right to harvest for food are being taught to hunt, trap and fish as well as harvesting foods that grow in the wild by a male relative. They will spend time with grandfathers to learn many skills. In some nations, the boys learn the Buffalo Dance. This teaching focuses on showing young men how to respect young women and their responsibilities when they become fathers. Girls are given more responsibilities regarding taking care of siblings and learning how to cook; especially in large families where there are many children. Women have more responsibilities in that they are more stationary; therefore, they tend to do most everything that has to do with taking care of the home, raising the children and knowing their place in the community. They are also shown skills such as sewing, beadwork, quillwork, tanning skins, doing laundry, etc. Those that follow ceremonies will spend time with the grandmothers to be taught the teachings of Moon Time (menses) and harvesting food and medicines. Within southernmost nations, they have adopted more of an agricultural and small game lifestyle due to better weather conditions. Both males and females learn to tend the crops, snare for small game and fish. Because males don’t have to go very far to harvest game, their role is more as a protector of the family and community. From a traditional/cultural viewpoint, they follow longhouse teachings depending on which nation they belong to. It is not uncommon for either sexes to go live with their grandparents to acquire their knowledge so that it can be passed down from generation to generation. It is also important to note that due to the residential school experience, many families have gone through colonization which has drastically altered their lifestyle; therefore, some families no longer practice their ancestral way of life.

Continuum of development

The Continuum of Development identifies several root social skills that are emerging in children. Between the ages of 5-8, friendships become increasingly important. Children start to have a “best friend”. Peer relationships are more stable because conflict resolution and problem-solving skills are improving. During these years, children are able to co-operate, share, help and show empathy for others. They are better able to self-regulate their behaviour because they are now capable of taking another person’s point of view and see how their behaviour affects someone else (Ontario Ministry of Education, 2014). Between the ages of 9-12, friends begin to have even more influence. This is referred to as “peer pressure”; the feeling that one must do what one’s peers are doing in order to be accepted by the group. Children this age start to want to put some physical and emotional distance between themselves and adults. They may begin to show interest in teen culture – music, social media, clothing and make-up. They feel strongly that they no longer want to be treated like a child (Ontario Ministry of Education, 2014).

social theories of development

Erik Erikson- Industry vs. Inferiority

Erik Erikson proposed that we are motivated by a need to achieve competence in certain areas of our lives. As we’ve learned in previous chapters, Erikson’s psychosocial theory has eight stages of development over the lifespan, from infancy through late adulthood. At each stage, there is a conflict, or task, that we need to resolve. Successful completion of each developmental task results in a sense of competence and a healthy personality. Failure to master these tasks leads to feelings of inadequacy.

During middle childhood (ages 6-12), children face the task of Industry versus Inferiority. Children begin to compare themselves to their peers to see how they measure up.

Figure 12.1: The academic award this child is receiving may contribute to their sense of industry. (Image by Janarthanan Kesavan is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0)

They either develop a sense of pride and accomplishment in their schoolwork, sports, social activities, and family life, or they feel inferior and inadequate when they don’t measure up (OpenStax, n.d.).

According to Erikson, children in middle childhood are very busy or industrious. They are constantly doing, planning, playing, getting together with friends, achieving. This is a very active time and a time when they are gaining a sense of how they measure up when compared with friends. Erikson believed that if these industrious children can be successful in their endeavours, they will get a sense of confidence for future challenges. If not, a sense of inferiority can be particularly haunting during middle childhood.

Sigmund Freud – Psychoanalytic Theory

The psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud (1856–1939) focused on unconscious, biological forces that he felt shape individual personality. Freud thought that the personality consists of three parts: the id, the ego, and the superego. The id is the selfish part of the personality and consists of biological instincts that all babies have, including the need for food and, more generally, the demand for immediate gratification. As babies get older, they learn that not all their needs can be immediately satisfied and thus develop the ego, or the rational part of the personality. As children get older still, they internalize society’s norms and values and thus begin to develop their superego, which represents society’s conscience. Freud believed that, in the event a child’s superego does not become strong enough, the individual is more at risk for being driven by the id to commit antisocial behaviour.

Figure 12.2: Development of the superego helps children overcome their unconscious desire to behave antisocially. (Image by Annie Spratt on Unsplash)

child and the family

One of the reasons we often turn out much like our parents is that our families are such an important part of our socialization process. When we are young, our primary caregivers are almost always one or both of our parents, either biological or non-biological. For several years we have more contact with them than with any other adults. Because this contact occurs in our most formative years, our parents’ interaction with us and the messages they teach us can have a profound impact throughout our lives. During middle childhood, children start to spend less time with parents and more time with peers. Parents often find that they have to modify their approach to parenting to accommodate the child’s growing independence. Using reason and engaging in joint decision-making whenever possible may be the most effective approach (Berk, 2007, as cited by Paris, Ricardo, Raymond, & Johnson, 2021).

Figure 12.3: When children grow up to love reading, they may have been influenced by the positive experiences of being read to by their families. (Image by San José Public Library is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0)

Family Atmosphere

One of the ways to assess the quality of family life is to consider the tasks of families. Berger (2005, as cited by Paris, Ricardo, Raymond, & Johnson, 2021) lists five family functions:

- Providing food, clothing and shelter

- Encouraging learning

- Developing self-esteem

- Nurturing friendships with peers

- Providing harmony and stability

Notice that in addition to providing food, shelter, and clothing, families are responsible for helping the child learn, relate to others, and have a confident sense of self. The family provides a harmonious and stable environment for living. A supportive home environment is one in which the child’s physical, cognitive, emotional, and social needs are adequately met. Sometimes families emphasize physical needs but ignore cognitive or emotional needs. Other times, families pay close attention to physical needs and academic requirement, but may fail to nurture the child’s friendships with peers or guide the child toward developing healthy relationships. Parents might want to consider how it feels to live in the household. Is it stressful and conflict-ridden? Is it a place where family members enjoy being? (Lally & Valentine-French, 2019).

Figure 12.4: This mother is encouraging learning in their child. (Image by Intel Free Press is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0)

The Family Stress Model

Family relationships are significantly affected by conditions outside the home. For instance, the Family Stress Model describes how financial difficulties are associated with parents’ depressed moods, which in turn could lead to marital problems and poor parenting that contributes to poorer child adjustment (Conger, Conger, & Martin, 2010, as cited by Paris, Ricardo, Raymond, & Johnson, 2021). Divorce is typically associated with economic stresses for children and parents, the renegotiation of parent-child relationships (with one parent typically as primary custodian and the other assuming a visiting relationship), and many other significant adjustments for children. Divorce is often regarded by children as a sad turning point in their lives, although for most it is not associated with long-term problems of adjustment (Emery, 1999, as cited by Paris, Ricardo, Raymond, & Johnson, 2021).

Indigenous Perspectives

Many Indigenous families live in poverty due to a lack of employment opportunities; especially in small and remote communities. Non-traditional ideologies of parental responsibilities, have further put indigenous children at risk. Also, as previously mentioned, the lack of schools in remote communities has forced families to be separated. Often, the child has to move to an urban setting with family friends or with extended family members to attend school which, in turn, creates more trauma for the child. Finally, the onset of intergenerational trauma from the legacy of residential schools and colonization has created cases of substance abuse, high rates of suicide, spousal abuse, and child neglect in many Indigenous communities.

Family Forms

As discussed previously in chapter 11, the sociology of the family examines the family as an institution and a unit of socialization. Sociological studies of the family look at demographic characteristics of the family members: family size, age, ethnicity and gender of its members, social class of the family, the economic level and mobility of the family, professions of its members, and the education levels of the family members.

Currently, one of the biggest issues that sociologists study are the changing roles of family members. The proportion of dual-earner Canadian families has roughly doubled in the last 40 years, from 36% of two parent families to 69%. Not only are more parents in the paid workforce; more dual-earner couples with children have two full-time working parents. As of 2015, 75% of dual-earner Canadian couples with children reported that both parents worked at least 30 hours per week (Statistics Canada, 2016). This dramatic increase in maternal employment is reflected in changing views about gender roles in the family. For example, in 1976 stay-at-home fathers accounted for roughly 1 in 70 families with a stay-at-home parent. By 2015, that ratio increased to 1 in 10 families (Statistics Canada, 2018).

What Families Look Like

Figure 12.5: a childless family (Image by Adam Jones is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

Figure 12.6: a single parent (father) family (Image is licensed under CC0

Figure 12.6: a single parent (father) family (Image is licensed under CC0

Figure 12.7: an extended family (Image by Joint Base Elmendorf-Richardson is in the public domain)

Figure 12.8: a same-sex family (Image by Surrogacy-UK is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0)

Figure 12.9: a single parent (mother) family (Image is in the public domain)

Figure 12.10: a nuclear family (Image by Army Medicine is licensed under CC BY 2.0)

Throughout this textbook and in the preceding images, you can see a variety of types of families. A few of these family types were introduced in Chapter 11. The sections below list some of the diverse types of families:

families without children

Singlehood family contains a person who is not married or in a common-law relationship. He or she may share a relationship with a partner but lead a single lifestyle. Couples that are childless are often overlooked in the discussion of families.

families with one parent

A single-parent family usually refers to a parent who has most of the day-to-day responsibilities in the raising of the child or children, who is not living with a spouse or partner, or who is not married. The dominant caregiver is the parent with whom the children reside for the majority of the time; if the parents are separated or divorced, children live with their custodial parent and have visitation with their noncustodial parent. In western society in general, following a separation a child will end up with the primary caregiver, usually the mother, and a secondary caregiver, usually the father.

Single parent by choice families refer to a family that a single person builds by choice. These families can be built with the use of assisted reproductive technology and donor gametes (sperm and/or egg) or embryos, surrogacy, foster or kinship care, and adoption.

two parent families

The nuclear family (also referred to as the elementary family or the conjugal family) is a family group consisting of 2 parents and their children. While common in industrialized cultures, it is not actually the most common type of family worldwide.

Cohabitation is an arrangement where two people who are not married live together in an intimate relationship, particularly an emotionally and/or sexually intimate one, on a long-term or permanent basis. Today, cohabitation is a common pattern among people in the Western world.

Indigenous Perspectives

Many Indigenous nations have a different outlook about marriage in which many do not get married; therefore, they would fall under cohabitating. Depending on whether the nation is matriarchal or patriarchal, the child would take on the last name of either the mother or the father. Some traditional families will have a traditional marriage; however, this is not as common today.

Blended families describe families formed when one or both parents with children from a former family create a new family. Blended families are complex in a number of ways that can pose unique challenges to those who seek to form successful relationships (Visher & Visher, 1985, as cited by Paris, Ricardo, Raymond, & Johnson, 2021).

families that include additional adults

Extended families include three generations, grandparents, parents, and children. This is the most common type of family worldwide.

Families by choice is increasingly being practiced by those who see benefits to including people beyond blood relatives in their families.

additional forms of families

Kinship families are those in which the full-time care, nurturing, and protection of a child is provided by relatives, members of the child’s First Nation, godparents, or other adults who have a family relationship to a child. When children cannot be cared for by their parents, research finds benefits to kinship care.

When a person assumes the parenting of another, usually a child, from that person’s biological or legal parent or parents this creates adoptive families. Legal adoption permanently transfers all rights and responsibilities and is intended to affect a permanent change in status and as such requires societal recognition, either through legal or religious sanction. As introduced in Chapter 2, adoption can be done privately, through an agency, or through foster care, both domestically or from abroad. Adoptions can be closed (no contact with birth/biological families or open, with different degrees of contact with birth/biological families). Couples, both opposite and same-sex, and single parents can adopt (although not all agencies and foreign countries will work with unmarried, single, or same-sex intended parents).

When parents are not of the same ethnicity, they build interracial families. There are parts of the world where marrying someone outside of your race (or social class) has legal and social ramifications. These families may experience issues unique to each individual family’s culture.

Indigenous Perspectives

In first nation communities there may not be a legal adoption; however, a child may be raised by an aunt and uncle, a close family friend or grandparents without any papers being signed. It is a mutual agreement between the family member and the adopted family. This way the biological parents can still have a part to play in the child’s life. Sometimes it is in the best interest of the child. Sometimes the child is taken care of by that family because the parents are not yet ready to rear children or they are pursuing their education to better their lives. It is a very unique way that I have come to appreciate. Many people may judge the families.

changes in families – divorce

The tasks of families listed above are functions that can be fulfilled in a variety of family types. Harmony and stability can be achieved in many family forms and when it is disrupted, either through divorce, or efforts to blend families, or any other circumstances, the child may suffer (Hetherington & Kelly, 2002, as cited by Paris, Ricardo, Raymond, & Johnson, 2021). Changes continue to happen, but for children they are especially vulnerable. Divorce and how it impacts children depends on how the caregivers handle the divorce as well as how they support the emotional needs of the child.

Figure 12.13: How divorce impacts children largely depends on how parents handle it. (Image by Tony Guyton is licensed under CC BY 2.0)

divorce

A lot of attention has been given to the impact of divorce on the life of children. The assumption has been that divorce has a strong, negative impact on the child and that single-parent families are deficient in some way. However, 75-80 percent of children and adults who experience divorce suffer no long-term effects (Hetherington & Kelly, 2002, as cited by Paris, Ricardo, Raymond, & Johnson, 2021). An objective view of divorce, re–partnering, and remarriage indicates that divorce, remarriage and life in blended families can have a variety of effects.

factors affecting the impact of divorce

As you look at the consequences (both pro and con) of divorce and remarriage on children, keep the previously mentioned family functions in mind. Some negative consequences are a result of financial hardship rather than divorce per se (Drexler, 2005, as cited by Paris, Ricardo, Raymond, & Johnson, 2021). Some positive consequences reflect improvements in meeting these functions. For instance, we have learned that a positive self-esteem comes in part from a belief in the self and one’s abilities rather than merely being complimented by others. In single-parent homes, children may be given more opportunity to discover their own abilities and gain independence that fosters self-esteem. If divorce leads to fighting between the parents and the child is included in these arguments, their self-esteem may suffer.

The impact of divorce on children depends on a number of factors. The degree of conflict prior to the divorce plays a role. If the divorce means a reduction in tensions, the child may feel relief. If the parents have kept their conflicts hidden, the announcement of a divorce can come as a shock and be met with enormous resentment. Another factor that has a great impact on the child concerns financial hardships they may suffer, especially if financial support is inadequate. Another difficult situation for children of divorce is the position they are put into if the parents continue to argue and fight—especially if they bring the children into those arguments.

Short-term consequences: In roughly the first year following divorce, children may exhibit some of these short-term effects:

1. Grief over losses suffered. The child will grieve the loss of the parent they no longer see as frequently. The child may also grieve about other family members that are no longer available. Grief sometimes comes in the form of sadness but it can also be experienced as anger or withdrawal. Older children may feel depressed.

2. Reduced Standard of Living. Very often, divorce means a change in the amount of money coming into the household. Children experience new constraints on spending or entertainment. School-aged children, especially, may notice that they can no longer have toys, clothing or other items to which they’ve grown accustomed. Or it may mean that there is less eating out or being able to afford cable television, and so on. The custodial parent may experience stress at not being able to rely on child support payments or having the same level of income as before. This can affect decisions regarding healthcare, vacations, rents, mortgages and other expenditures. And the stress can result in less happiness and relaxation in the home. The parent who has to take on more work may also be less available to the children.

3. Adjusting to Transitions. Children may also have to adjust to other changes accompanying a divorce. The divorce might mean moving to a new home and changing schools or friends. It might mean leaving a neighbourhood that has meant a lot to them as well.

Long-term consequences: Here are some effects that go beyond just the first year following divorce:

1. Economic/Occupational Status. One of the most commonly cited long-term effects of divorce is that children of divorce may have lower levels of education or occupational status. This may be a consequence of lower income and resources for funding education rather than to divorce per se. In those households where economic hardship does not occur, there may be no impact on economic status (Drexler, 2005, as cited by Paris, Ricardo, Raymond, & Johnson, 2021).

2. Improved Relationships with the Custodial Parent (usually the mother): Most children of divorce lead happy, well-adjusted lives and develop stronger, positive relationships with their custodial parent (Seccombe and Warner, 2004, as cited by Paris, Ricardo, Raymond, & Johnson, 2021). Others have also found that relationships between mothers and children become closer and stronger (Guttman, 1993, as cited by Paris, Ricardo, Raymond, & Johnson, 2021) and suggest that greater equality and less rigid parenting is beneficial after divorce (Steward, Copeland, Chester, Malley, and Barenbaum, 1997, as cited by Paris, Ricardo, Raymond, & Johnson, 2021).

3. Greater emotional independence in sons. Drexler (2005, as cited by Paris, Ricardo, Raymond, & Johnson, 2021) notes that sons who are raised by mothers only develop an emotional sensitivity to others that is beneficial in relationships.

4. Feeling more anxious in their own love relationships. Children of divorce may feel more anxious about their own relationships as adults. This may reflect a fear of divorce if things go wrong, or it may be a result of setting higher expectations for their own relationships.

5. Adjustment of the custodial parent. Furstenberg and Cherlin (1991, as cited by Paris, Ricardo, Raymond, & Johnson, 2021) believe that the primary factor influencing the way that children adjust to divorce is the way the custodial parent adjusts to the divorce. If that parent is adjusting well, the children will benefit. This may explain a good deal of the variation we find in children of divorce.

Figure 12.14: Jeanette Wilinski is the mother of Elizabeth, Logan and Alexis. A single mom has to find a balance between taking care of the Air Force mission and taking care of their children. (Image by the Scott Air Force Base is in the public domain)

Families are the most important part of the 6 to 12-year-old life. However, peers and friendships become more and more important to the child in middle childhood.

Friendships, Peers, and Peer groups

Parent-child relationships are not the only significant relationships in a child’s life. Friendships take on new importance as judges of one’s worth, competence, and attractiveness. Friendships provide the opportunity for learning social skills such as how to communicate with others and how to negotiate differences. Children get ideas from one another about how to perform certain tasks, how to gain popularity, what to wear, say, and listen to, and how to act. This society of children marks a transition from a life focused on the family to a life concerned with peers. Peers play a key role in a child’s self-esteem at this age as any parent who has tried to console a rejected child will tell you. No matter how complimentary and encouraging the parent may be, being rejected by friends can only be remedied by renewed acceptance (Lumen Learning, n.d.).

Figure 12.15: Peers influence a child’s self-esteem. (Image by Robins Air Force Base is in the public domain)

Children’s conceptualization of what makes someone a “friend” changes from a more egocentric understanding to one based on mutual trust and commitment. Both Bigelow (1977) and Selman (1980) (as cited by Paris, Ricardo, Raymond, & Johnson, 2021) believe that these changes are linked to advances in cognitive development. Bigelow and La Gaipa (1975, as cited in Lumen Learning, n.d.)) outline three stages to children’s conceptualization of friendship .

Table 12.1: Three Stages to Children’s Conceptualization of Friendship

| STAGE | DESCRIPTIONS |

| Stage One | In stage one, reward-cost, friendship focuses on mutual activities. Children in early, middle, and late childhood. |

| Stage Two | In stage two, normative expectation, focuses on conventional morality; that is, the emphasis is on a friend as someone who is kind and shares with you. Clark and Bittle (1992) found that fifth graders emphasized this in a friend more than third or eighth graders. |

| Stage Three | In stage three, empathy and understanding, friends are people who are loyal, committed to the relationship, and share intimate information. Clark and Bittle (1992) reported eighth graders emphasized this more in a friend. They also found that as early as fifth grade, girls were starting to include the sharing of secrets and not betraying confidences as crucial to someone who is a friend. |

Table 12.1: Three Stages to Children’s Conceptualization of Friendship (Lifespan Development – Module 6: Middle Childhood by Lumen Learning references Psyc 200 Lifespan Psychology by Laura Overstreet, licensed under CC BY 4.0)

Friendships are very important for children. The social interaction with another child who is similar in age, skills, and knowledge provokes the development of many social skills that are valuable for the rest of life (Bukowski, Buhrmester, & Underwood, 2011, as cited by Paris, Ricardo, Raymond, & Johnson, 2021). In these relationships, children learn how to initiate and maintain social interactions with other children. They learn skills for managing conflict, such as turn-taking, compromise, and bargaining. Play also involves the mutual, sometimes complex, coordination of goals, actions, and understanding. Through these experiences, children develop friendships that provide additional sources of security and support to those provided by their parents (Lally & Valentine-French, 2019).

five stages of friendship from early childhood through adulthood

Selman (1980, as cited by Lally & Valentine-French, 2019) outlines five stages of friendship from early childhood through to adulthood:

- In stage 0, momentary physical interaction, a friend is someone who you are playing with at this point in time. Selman notes that this is typical of children between the ages of three and six. These early friendships are based more on circumstances (e.g., a neighbour) than on genuine similarities.

- In stage 1, one-way assistance, a friend is someone who does nice things for you, such as saving you a seat on the school bus or sharing a toy. However, children in this stage, do not always think about what they are contributing to the relationships. Nonetheless, having a friend is important and children will sometimes put up with a not so nice friend, just to have a friend. Children as young as five and as old as nine may be in this stage.

- In stage 2, fair-weather cooperation, children are very concerned with fairness and reciprocity, and thus, a friend is someone who returns a favour. In this stage, if a child does something nice for a friend there is an expectation that the friend will do something nice for them at the first available opportunity. When this fails to happen, a child may break off the friendship. Selman found that some children as young as seven and as old as twelve are in this stage.

- In stage 3, intimate and mutual sharing, typically between the ages of eight and fifteen, a friend is someone who you can tell them things you would tell no one else. Children and teens in this stage no longer “keep score,” and do things for a friend because they genuinely care for the person. If a friendship dissolves in this stage it is usually due to a violation of trust. However, children in this stage do expect their friend to share similar interests and viewpoints and may take it as a betrayal if a friend likes someone that they do not.

- In stage 4, autonomous interdependence, a friend is someone who accepts you and that you accept as they are. In this stage children, teens, and adults accept and even appreciate differences between themselves and their friends. They are also not as possessive, so they are less likely to feel threatened if their friends have other relationships or interests. Children are typically twelve or older in this stage.

Peer groups

Peer relationships can be challenging as well as supportive (Rubin, Coplan, Chen, Bowker, & McDonald, 2011, as cited by Paris, Ricardo, Raymond, & Johnson, 2021). Being accepted by other children is an important source of affirmation and self-esteem, but peer rejection can foreshadow later behaviour problems (especially when children are rejected due to aggressive behaviour). With increasing age, children confront the challenges of bullying, peer victimization, and managing conformity pressures. Social comparison with peers is an important means by which children evaluate their skills, knowledge, and personal qualities, but it may cause them to feel that they do not measure up well against others. For example, a child who is not athletic may feel unworthy of their football-playing peers and revert to shy behaviour, isolating themselves and avoiding conversation. Conversely, an athlete who doesn’t “get” Shakespeare may feel embarrassed and avoid reading altogether.

Figure 12.16: Social comparison with peers is an important means by which children evaluate their value. (Image by the U.S Army is in the public domain)

Also, with the approach of adolescence, peer relationships become focused on psychological intimacy, involving personal disclosure, vulnerability, and loyalty (or its betrayal)—which significantly affect a child’s outlook on the world. Each of these aspects of peer relationships require developing very different social and emotional skills than those that emerge in parent-child relationships. They also illustrate the many ways that peer relationships influence the growth of personality and self-concept (Lally & Valentine-French, 2019).

Peer relationships

Most children want to be liked and accepted by their friends. Some popular children are nice and have good social skills. These popular-prosocial children tend to do well in school and are cooperative and friendly. Popular-antisocial children may gain popularity by acting tough or spreading rumours about others (Cillessen & Mayeux, 2004, as cited by Paris, Ricardo, Raymond, & Johnson, 2021). Rejected children are sometimes excluded because they are shy and withdrawn. The withdrawn-rejected children are easy targets for bullies because they are unlikely to retaliate when belittled (Boulton, 1999, as cited by Paris, Ricardo, Raymond, & Johnson, 2021). Other rejected children are ostracized because they are aggressive, loud, and confrontational. The aggressive-rejected children may be acting out of a feeling of insecurity. Unfortunately, their fear of rejection only leads to behaviour that brings further rejection from other children. Children who are not accepted are more likely to experience conflict, lack confidence, and have trouble adjusting.

Figure 12.17: Peer relationships are particularly important for children. They can be supportive but also challenging. Peer rejection may lead to behavioural problems later in life. (Image by tup wanders is licensed under CC BY 2.0)

Peer Relationships are studied using sociometric assessment (which measures attraction between members of a group). Children are asked to mention the three children they like to play with the most, and those they do not like to play with. The number of times a child is nominated for each of the two categories (like and do not like) is tabulated.

Table 12.2: Categories in Peer Relationships

| Category | Description |

| Popular | Receive many votes in the “like” category, and very few in the “do not like” category. |

| Rejected | Receive more unfavourable votes, and few favourable ones. |

| Controversial | Mentioned frequently in each category, with several children liking them and several children placing them in the do not like category. |

| Neglected | Rarely mentioned in either category. |

| Average | Have a few positive votes with very few negative ones. |

| Popular-prosocial | Are nice and have good social skills; tend to do well in school and are cooperative and friendly. |

| Popular-antisocial | May gain popularity by acting tough or spreading rumours about others. |

| Rejected-withdrawn | Are shy and withdrawn and are easy targets for bullies because they are unlikely to retaliate when belittled. |

| Rejected-aggressive | Are ostracized because they are aggressive, loud, and confrontational. They may be acting out of a feeling of insecurity. |

Indigenous Perspectives

For a child that lives in a First Nation (FN) community, peer relationships will differ from that of a child who lives in an urban setting where there may be a variety of choices. In small remote communities, they will not have as much selection regarding peer relationships. Some children might not have a choice regarding friendships.

During middle childhood, children start to spend less time with parents and more time with peers. Parents often find that they have to modify their approach to parenting to accommodate the child’s growing independence. In small and/or remote FN communities, a child’s peer may well be a cousin or another close relative due to a smaller population. This unique relationship is more like a sibling relationship. Other peers become like cousins. Much of their life from the time they are able to play outside alone, at school or at community functions is spent playing and exploring with peers that are more like cousins. There is a sense of safety on a FN community because everyone in the community watches out for the children. Children might gain independence at an earlier age than that of a child in a city or bigger urban setting. Often, the parents of their peer/adopted cousin become aunties and uncles. They are very much a part of the child’s life in regards to the roles that aunties and uncles play as mentioned in a comment from a previous chapter; they are the disciplinarian. Parenting styles are very different in FN communities. In large family structures, the older siblings are given the task of helping to rear their younger siblings.

aggression, antisocial behaviour, bullies and victims

Aggression and Antisocial Behaviour

Aggression may be physical, verbal or emotional. Aggression is activated in large part by the amygdala and regulated by the prefrontal cortex.

Figure 12.18: This child is threatening with physical aggression. (Image by Philippe Put is licensed under CC BY 2.0)

Testosterone is associated with increased aggression in both males and females. Aggression can be caused by negative experiences and emotions, including frustration and pain. Heat has also been shown to increase aggressive behaviour. Psychologist Craig Anderson studied archival data and found the rate of violent crimes increases with temperature (Anderson, 2001). Finally, as predicted by principles of observational learning, research evidence makes it very clear that, on average, people who watch violent behaviour become more aggressive. Early, antisocial behaviour leads to befriending others who also engage in antisocial behaviour, which only perpetuates the downward cycle of aggression and wrongful acts (Lally & Valentine-French, 2019).

Bullying and Victims

According to the Government of Canada (2016), bullying is defined as “willful, repeated aggressive behaviour with negative intent used by a child to maintain power over another child”. There are different types of bullying, including verbal bullying, which is saying or writing mean things, teasing, name-calling, taunting, threatening, or making inappropriate sexual comments. Social bullying, also referred to as relational bullying, involves spreading rumours, purposefully excluding someone from a group, or embarrassing someone on purpose. Physical bullying involves hurting a person’s body or possessions.

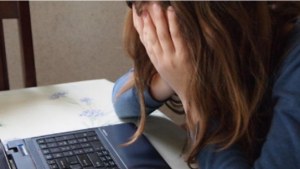

A more recent form of bullying is cyberbullying, which involves electronic technology. Examples of cyberbullying include sending mean text messages or emails, creating fake profiles, and posting embarrassing pictures, videos or rumours on social networking sites. Children who experience cyberbullying have a harder time getting away from the behaviour because it can occur any time of day and without being in the presence of others.

Figure 12.19: Cyberbullying can be devastating for children. (Image on Pixabay)

Those at Risk for Bullying

Bullying can happen to anyone but some students are at an increased risk for being bullied, including lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgendered, queer, two spirit (LGBTQ2S) youth, those with disabilities, and those who are socially isolated. Additionally, those who are perceived as different, weak, less popular, overweight, or having low self-esteem, have a higher likelihood of being bullied.

Those Who are More Likely to Bully

Bullies are often thought of as having low self-esteem, and then bully others to feel better about themselves. Although this can occur, many bullies in fact have high levels of self-esteem. They possess considerable popularity and social power and have well-connected peer relationships. They do not lack self-esteem, and instead lack empathy for others. They like to dominate or be in charge of others.

Bullied Children

Unfortunately, most children do not let adults know that they are being bullied. Some fear retaliation from the bully, while others are too embarrassed to ask for help. Those who are socially isolated may not know who to ask for help or believe that no one would care or assist them if they did ask for assistance. Consequently, it is important for parents and teachers to know the warning signs that may indicate a child is being bullied. These include: unexplainable injuries, lost or destroyed possessions, changes in eating or sleeping patterns, declining school grades, not wanting to go to school, loss of friends, decreased self-esteem and/or self-destructive behaviours.

Summary

- Erikson’s fourth stage of industry vs. Inferiority

- The role of the family and different forms of families

- Divorce and how it changes the family

- The importance of peers and friendships

- Children in peer groups and types of friendships

- Consequences of peer acceptance or rejection

References

Anderson, C. (2001). Heat and Violence. Retrieved from https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1111/1467-8721.00109

Government of Canada. (2016). How to recognize bullying. Retrieved from https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/bullying/how-recognize-bullying.html

Lally, M. & Valentine-French, S. (2019). Lifespan development: A psychological perspective (2nd ed.). Retrieved from http://dept.clcillinois.edu/psy/LifespanDevelopment.pdf

Lumen Learning. (n.d.). Lecture: Middle childhood. In Lifespan development. Retrieved from https://courses.lumenlearning.com/lifespandevelopment2/chapter/lecture-middle-childhood/

Ontario Ministry of Education. (2014). Excerpts from “Elect”. Retrieved from https://www.dufferincounty.ca/sites/default/files/rtb/Excerpts-from-Early-Learning-for-Every-Child-Today.pdf

OpenStax. (n.d.). Psychology: 9.1 Lifespan theories. Retrieved from https://openstax.org/books/psychology/pages/9-2-lifespan-theories

Statistics Canada. (2018). Changing profile of stay-at-home parents. Retrieved from https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/11-630-x/11-630-x2016007-eng.htm

Statistics Canada. (2016). The rise of the dual earner family with children. Retrieved from https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/11-630-x/11-630-x2016005-eng.htm