Chapter 4: Violence Against Women

Chapter Summary

- Overview

- Profile: Chouchou Namegabe

- Project: Gender Equality and Combating Domestic Violence

- Questions

- Additional Resources

The chapter discusses the breadth and severity of violence against women with case studies of organizing and resistance against sexualized and domestic violence from the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and the Peoples’ Republic of China. Globally, it is estimated that one-third of women have been beaten, raped or abused. Factors influencing violence against women include female genital mutilation (FGM), child-marriage, forced marriages, and various forms of labour exploitation. However, communities are currently addressing violence against women through awareness campaigns, shelters and victim support services, demands for enhanced criminal justice responses, and advocacy for more robust laws regulating offenders and protecting victims.

Two case studies of both grassroots and policy-focused non-governmental organizations (NGOs) working to address violence against women. Chouchou Namegabe is a prolific journalist, producer and activist who founded the Association de Femmes des Médias de Sud Kivu (AFEM). The organization provides a space for women to speak and be heard about the gender-based violence they have experienced and engages in policy advocacy on an international scale. The Anti-Violence Network of the China Law Association (ADVN) has also been active in influencing progress on legislation, investigation, prosecution of crimes, social support, and public awareness on violence against women. The ADVN has a collaborative relationship with government and takes a long-term approach that they believe is necessary to influence legislative changes and implementation of the law.

Key Words

- Anti-Domestic Violence Network of China Law Association (ADVN)

- Association des Femmes des Médias de Sud Kivu (AFEM)

- China Law Association

- China Women’s University

- Chouchou Namegabe

- Declaration on the Elimination of Violence against Women

- Human Rights Centre of the University of Oslo

- Honour killings

- Female genital mutilation (FGM)

- Ford Foundation

- Oxfam Novib

- Radio Maendeleo

- Swedish International Development Agency (SIDA)

- Trafficking

- World Health Organization (WHO)

- Zeng Guohua

Overview

By Robin N. Haarr

Violence against women is a serious human rights violation and a public health problem of global proportions. The Declaration on the Elimination of Violence against Women, adopted by the United Nations General Assembly in 1993, defines violence against women as “any act of gender-based violence that results in, or is likely to result in, physical, sexual or psychological harm or suffering to women, including threats of such acts, coercion or arbitrary deprivation of liberty, whether occurring in public or in private life.”

A Serious and Common Problem

International research, conducted over the past two decades by the World Health Organization and others, reveals that violence against women is a much more serious and common problem than previously suspected. It is estimated that one out of three women worldwide has been raped, beaten or abused. While violence against women occurs in all cultures and societies, its frequency varies across countries. Societies that stress the importance of traditional patriarchal practices which reinforce unequal power relations between men and women and keep women in a subordinate position tend to have higher rates of violence against women. Rates tend to be higher in societies in which women are socially regulated or secluded in the home, excluded from participation in the economic labor market and restricted from owning and inheriting property. It is more prevalent where there are restrictive divorce laws, a lack of victim support services and no legislation that effectively protects female victims and punishes offenders. Violence against women is a consequence of gender inequality, and it prevents women from fully advancing in society.

Two of the most common and universal forms of violence against women are intimate partner violence and sexual violence. Intimate partner violence by a current or former male partner or spouse is a serious, but preventable form of violence that affects millions of women worldwide. The violence can be emotional, economic, psychological or physical, including sexual abuse and murder. In countries where reliable, large-scale studies have been conducted, between 10 percent and 71 percent of women report they have been physically or sexually abused, or both, by an intimate partner (WHO). Intimate partner violence is so deeply embedded in many cultures and societies that millions of women consider it an inevitable part of life and marriage. Many battered women suffer in silence because they fear retribution and negative repercussions and stigmatization for speaking out.

Sexual violence includes harassment, assault and rape. It is a common misperception that women are at greater risk of sexual violence from strangers; in reality, women are most likely to experience sexual violence from men they are intimate with or know. During times of war and armed conflict, rape and sexual violence perpetrated upon women are systematically used as a tactic of war by militaries and enemy groups to further their political objectives.

Cultural Factors and Domestic Violence

In many parts of the world, violence against women and girls is based upon cultural and historical practices. In some parts of the world, particularly in Africa and the Middle East, female genital mutilation is a common form of violence against women. There are also forms of violence against women and girls related to marriage — child marriage, forced arranged marriages, bride kidnappings, and dowry-related deaths and violence. Child marriage and forced marriages are common in Africa, South and Central Asia, and the Middle East. South Asia reportedly has some of the highest rates of child marriages in the world. In South Asia, young women are murdered or driven to suicide as a result of continuous harassment and torture by husbands and in-laws trying to extort more dowry from the bride and her family. In other parts of the world, such as Central Asia, the Caucasus region and parts of Africa, women are at risk of bride kidnappings or marriage by capture, in which a man abducts the woman he wishes to marry. Honor killings — the killing of females by male relatives to restore family honor — are deeply rooted in some cultures where women are considered the property of male relatives and are responsible for upholding family honor. This is the case particularly in the Middle East, South Asia and Africa. Honor killings have even occurred in immigrant communities in Europe and North America. A woman can be killed for talking to a male who is not a relative, consensual sexual relations outside of marriage, being raped, refusing to marry the man of her family’s choice, disrespecting her husband or seeking a divorce.

Finally, trafficking of women and girls for sexual exploitation, marriage, domestic servitude and labor is another form of violence against women. Women are deceived and coerced by traffickers who promise jobs and the opportunity for a better life. Parents sell their daughters for small sums of money or promises of remittances for the child’s labor. Traffickers often target poor and vulnerable communities, but young women seeking to study or work abroad can also be at risk. Trafficking is a modern-day form of slavery that affects millions of women and girls worldwide.

Concerted Efforts Needed

Every year millions of women require medical attention as a result of violence. Victims suffer disfigurement, disability and death. Physical and mental health problems often continue long after the violence ends. Some women commit suicide to escape the violence in their lives. Across the globe, women are addressing violence in different ways, including awareness-raising campaigns, crisis centers and shelters for female victims, victim support services (medical care, counseling and legal services) and demanding enhanced criminal justice responses and laws that effectively protect female victims of violence and punish offenders. Violence against women is preventable, but it requires the political will of governments, collaboration with international and civil society organizations and legal and civil action in all sectors of society.

Robin Haarr is a professor of criminal justice at Eastern Kentucky University whose research focuses on violence against women and children and human trafficking, nationally and internationally. She does research and policy work for the United Nations and U.S. embassies, and has received several awards for her work, including induction into the Wall of Fame at Michigan State University’s School of Criminal Justice and the CoraMae Richey Mann “Inconvenient Woman of the Year” Award from the American Society of Criminology, Division on Women and Crime.

PROFILE: Chouchou Namegabe – A Fierce Voice Against Sexual Violence

By Solange Lusiku

Journalist, radio broadcast producer and co-founder of the South Kivu Women’s Media Association, which she currently heads, activist Chouchou Namegabe is fiercely dedicated to fighting violence against women. She focuses on eradicating sexual violence used as a weapon of war, a practice that has afflicted the eastern part of the Democratic Republic of the Congo for more than a decade.

Born on March 30, 1978, Namegabe took up the fight for women’s rights early. Her secondary school education and experience in community radio spurred her interest in the struggle that now defines her. Namegabe began her broadcasting career in 1997 as a trainee at Radio Maendeleo, a popular local radio station. She continued to volunteer, and eventually became a permanent staff member. As violence intensified in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), she focused her reporting on women, health and human rights, and on exposing government corruption. AFEM (Association des Femmes des Médias de Sud Kivu) was founded in 2003, and she became its president in 2005. She has used the association and her role as a broadcaster as effective vehicles to disseminate the voices of women — especially rural women — who are victims of the conflict.

“Listening Clubs” Break the Silence

Namegabe works with other women throughout the DRC to set up “listening clubs” where abused women may share their stories. Convincing women who have been raped and tortured to break their silence and speak about their horrific experiences has been a major achievement for Namegabe and AFEM. Residents of Bukavu and all eight territories of South Kivu Province can hear firsthand the tragic stories of these women on local radio, thanks to her efforts. Talking about sexual abuse and murder is no longer forbidden, but has become a weapon against this devastating scourge in the eastern DRC. Namegabe recognized that rape was so prevalent in the region that the stories must be told to bring about change. She promoted this idea on the radio and among her female journalist coworkers. A practical woman, she backed her words with action. In 2007, despite odds against success, Namegabe organized a campaign in Bukavu she called “Break the Silence: Media Against Sexual Violence.” This campaign was universally well-received among peace-loving women, who value the physical integrity of human beings.

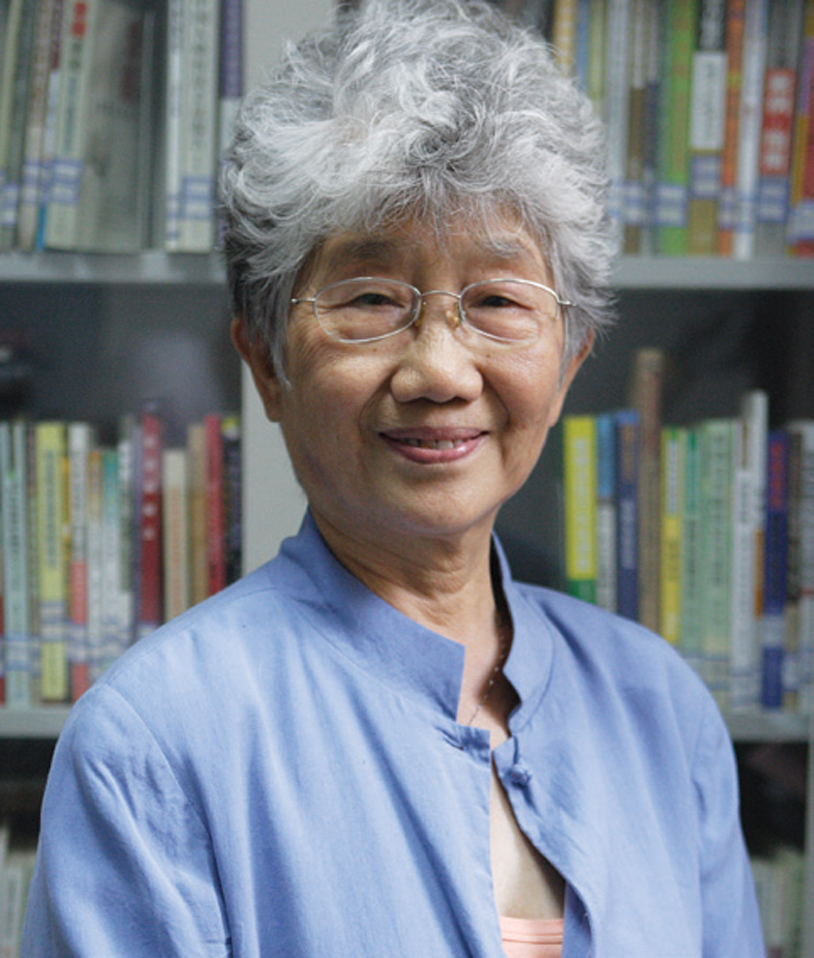

Women’s rights activist Chouchou Namegabe testified before the U.S. Senate Foreign Relations Committee in 2009 about rape and other forms of violence against women in conflict zones. She stands on the steps of the U.S. Capitol in Washington, D.C.

Although they live in turbulent areas that suffer sporadic incursions by rebels and other armed militia, many rural women have regained their self-confidence and have overcome the shame of sharing their tragedy with their friends and family. They gradually are moving past their trauma through speaking out:

“I was raped, and my genitals were mutilated.”

“They came with these horrible beards. They ordered me to lie down on the ground. They took off my clothes and raped me in front of my husband and children. There were seven of them, eight. After that I don’t remember because I was unconscious.”

Ending Abuse and Rape as Weapons of War

The people of South Kivu heard such statements during different on-site radio broadcasts hosted by AFEM members. Under Chouchou Namegabe’s leadership, AFEM developed contacts with women everywhere they went in South Kivu. The results are encouraging. Slowly but surely, women are becoming more comfortable talking about violent sexual abuse and the taboos related to openly discussing sex are disappearing as a result of AFEM’s work in South Kivu to raise awareness about the problem. Women have dared to challenge not only rape, but other abusive and discriminatory practices.

Namegabe and her AFEM colleagues have expanded their campaign to reach international audiences. They have attended hearings at the International Criminal Court at The Hague, where they have convinced other journalists to join their fight to save women in South Kivu from rape and torture as a weapon of war.

Namegabe also appeared before the U.S. Senate to testify about the atrocities committed against Congolese women. She told the Senate Foreign Relations Committee in May 2009, “Rape and sexual violence [are] used as a weapon and tactic of war to destroy the community. The rapes are targeted and intentional, and are meant to remove the people from their mineral-rich land through fear, shame, violence, and the intentional spread of HIV throughout entire families and villages.” Her voice choked with tears, she continued: “We have interviewed over 400 women in South Kivu, and their stories are terrifying. In fact, the word rape fails to truly describe what is happening, because it is not only rape that occurs, but atrocities also accompany the rapes.” A mother was taken with her five children to the forest, Namegabe said, “As each day passed the rebels killed one of her children and forced her to eat her child’s flesh. She begged to be killed but they refused and said ‘No, we can’t give you a good death.’” In other cases women’s genitals were set on fire “not to kill them but to let them suffer.”

Chouchou Namegabe wants to ensure that these brutalities are recognized in the DRC as crimes against humanity, and the perpetrators prosecuted. She has called for impunity on rape and sexual violence to end, for governments and corporations to “end the profitability of blood minerals” and mandate that Congolese minerals are “conflict free.” She also helps rehabilitate the victims of violence. “Economic recovery is part of the total recovery of the women and their communities,” she told the U.S. senators.

The visible results that this fighter for justice facilitated earned her international recognition, including the prestigious Vital Voices Global Leadership award and the Knight International Journalism award from the International Center for Journalists in Washington, D.C. Namegabe continues to raise awareness about the plight of Congolese women and encourages female victims of sexual violence to break their silence, because there is power in truth.

Solange Lusiku, a journalist in the Democratic Republic of Congo, edits the only newspaper in Bukavu, South Kivu. She worked more than a decade in broadcasting, is married and the mother of five children.

PROJECT: Gender Equality and Combating Domestic Violence

By Qin Liwen

In China, a nongovernment organization called the Anti-Domestic Violence Network has worked to end domestic violence for 10 years through education, social support and advocacy for legislation that protects women.

Zheng Guohua, a 51-year-old survivor of domestic violence, speaks in a cheerful voice that belies the two decades of abuse she is describing. In one 1998 incident, Zheng was so severely beaten by her husband that her spleen was ruptured and had to be removed. She says her father, devastated by her mistreatment, died from a brain hemorrhage. “I knelt at my father’s grave, crying and laughing. I told him, ‘Dad, I promise you, I will [have] revenge!’” says Zheng. “I think I was [awakened] by my father’s death. And I realized that this bad guy (her ex-husband) must be punished. I can’t let him harm people anymore!”

An often bruised and terrified Zheng sought help from family members, neighbors, village cadres, county police and the county Women’s Federation. People in her village repeatedly warned her husband and once beat him up, but that didn’t stop his abuse. Police ignored her because “meddling with domestic affairs” was not their duty — and was even considered inappropriate. The poorly-funded local Women’s Federation couldn’t do anything to help; no one took the organization seriously.

Shaken by the death of her father and determined to do something, in 1999 Zheng ran away from her village home to Shijiazhuang, the provincial capital. Finally, she found help. A letter issued by the Women’s Federation of Hebei Province spurred the local police into action. Her then-husband was arrested and sentenced to four years in jail.

Zheng was lucky. She was supported by an organization that is part of a strong anti-domestic violence movement in China, headed by the Anti-Domestic Violence Network of China Law Association (ADVN). In 2001, a new clause of the Marriage Law made domestic violence illegal. The ADVN played an important role in the adoption of that clause. Today, Zheng is remarried, farming on a piece of rented land in her village.

Inspired by the international gender equality movement and the 1995 World Conference on Women in Beijing, a group of Chinese women activists set up the ADVN in June 2000. The ADVN is dedicated to achieving gender equality in China. It was the first — and remains the largest — anti-domestic violence organization in China, and it is responsible for significant progress in legislation, investigation and prosecution of crimes, social support and public awareness. “Ten years ago nobody would even think that beating up wives is a crime. Now many people know about it,” says ADVN co-founder, Li Hongtao, who is director of the Library of China Women’s University. “And more and more police, judges and procurators (prosecutors and investigators) are learning that they should take actions against it.”

The ADVN now boasts 118 individual members and 75 group members such as women’s federations, research institutes and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs). Every three years the ADVN identifies a number of projects and selects the most suitable organizational members to conduct the work. Each project is strictly monitored and evaluated. Most concern education and advocacy about domestic violence.

A co-founder and chief coordinator of the early ADVN project management committee, Chen Mingxia, explains its success. “From the very beginning we chose to associate with the China Law Society, an NGO within the [political] system. First because we thought legislation is fundamental for the anti-domestic violence movement. Second, the China Law Association has ready access to the essential, relevant government branches like legislative, juridical and public security offices and is trusted by them.” In China, NGOs are strictly regulated by the government’s civil affairs office and are often mistrusted by officials if they are not connected with government. So NGOs such as ADVN use creative, non-confrontational ways of persuading male officials to accept their ideas. “But we also keep the independent identity and operation as an NGO, so that the prospects and goals of ADVN can be reached relatively smoothly step by step,” says Chen.

The other strategic advantage of the ADVN is its open and democratic structure. It is open to any individual or organization that wants to contribute to the shared goal of stopping domestic abuse of women. Strategic goals are set and big decisions are made democratically among representatives across the network, no matter how much debate surrounds issues. This keeps ADVN members active and committed to implementing plans.

“I am happy to work here, because people in this organization are all so kind and idealistic. Everyone believes in what they are doing,” says Dong Yige, a young graduate from Chicago University who has worked for ADVN for a year. “The democratic atmosphere is invigorating.”

Born in August 1940, Chen Mingxia thinks her generation was well educated in gender equality by the Communist government founded in 1949. Chen became a researcher at the Institute for Legal Research of the China Academy of Social Sciences, specializing in marriage laws and women’s rights, and she was the former Deputy Director of the Marriage Law Association within the China Law Association. Many ADVN co-founders were scholars, government officials, teachers — elite women of Chen’s generation or one generation later.

ADVN activists still see much work ahead. “We have all these extremely successful cases in different regions: community actions against domestic violence in You’anmen, Beijing; or the training program for public security bureau chiefs in Hunan Province,” says Chen. “But these are not enough. We should urge the government to take up the responsibility of anti-domestic violence.”

Meanwhile, the ADVN’s long-time sponsors, Ford Foundation (United States), the Swedish International Development Agency (SIDA), Oxfam Novib (Netherlands) and the Human Rights Center of the University of Oslo (Norway), are changing their sponsorship levels. That means ADVN must learn how to raise funds for its projects — and it is doing so.

“Legislation takes time, and it takes even longer to implement a new law under completely different situations across China. Changing ideas is a gradual process. Too many gaps [need] to be filled. We knew it from the beginning, and we’re patient. We will march forward,” Chen promises.

Qin Liwen is the Director of News Center, Modern Media Group, China. She has worked for several major print and online publications in Singapore and China since 2000 and is the author of several books, including News Is Cruel (2003) and The Adventure of Ideas (2004).

Multiple Choice Quiz

Questions

- The World Health Organization estimates that _________ women worldwide have been raped, beaten, or abused.

- One out of ten

- One out of fifteen

- One out of three

- One out of five

- None of the above

- The following factor(s) increase(s) a society’s level of violence against women….

- Equal power relations between men and women

- Higher employment rates for women

- Restrictions on women owning and inheriting property

- Socially restricting women to the home

- Both C and D

- According to the chapter, two of the most common forms of violence against women are…

- Psychological violence and physical violence

- Sexual violence and non-sexual violence

- Structural violence and systemic violence

- Intimate partner violence and sexual violence

- None of the above

- Sexual violence includes…

- Harassment

- Sexual assault

- Rape

- All of the above

- None of the above

- The chapter does NOT discuss at length examples of cultural factors that exacerbate violence against women in…

- Africa

- South and Central Asia

- The Middle East

- North America

- All of the above

- The notion of honour killings includes instances where a woman is killed for…

- Talking to a man who is not her relative

- Consensual sexual relations outside of marriage

- Being raped

- Refusing to marry the man of her family’s choice

- All of the above

- According to the chapter, trafficking includes…

- Forced deportations of women and girls to their countries of origin by governments

- Detention by state or government bodies

- The sale of daughters by parents into forced labour for remittances

- Restrictive labour conditions imposed by temporary labour visas

- None of the above

- The chapter conceptualizes the ‘victims’ of trafficking as…

- Potentially women, men and children of any gender

- Women and girls

- Migrant workers in exploitative situations

- All of the above

- None of the above

- Chouchou Namegabe became president of….

- Radio Maendeleo

- Association des Femmes des Médias de Sud Kivu (AFEM)

- The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC)

- South Kivu Province

- None of the above

- AFEM empowers women that have experienced violence by…

- Encouraging them to break their silence and speak about their experiences

- Pursuing direct legal action against their perpetrators

- Meeting individually with the authorities to file police reports

- Actively intervening in situations where women are being harassed

- All of the above

- The results of the AFEM program include…

- Women feel increasingly comfortable discussing sexualized violence

- Taboos surrounding the discussion of sex are disappearing

- Stigma is increasing around rape and harassment

- The prevalence of sexual assault is decreasing

- Both A and B

- According to Namegabe, what is the fundamental cause of the violence against women in the DRC specifically?

- Patriarchy

- The process of population removal to access Congolese minerals

- Fear and shame

- The intentional spread of HIV throughout families and villages

- None of the above

- According to the chapter, which women’s organization was inspired by the 1995 World Conference on Women in Beijing?

- China Law Society

- Marriage Law Association

- Modern Media Group

- Anti-Domestic Violence Network (ADVN)

- The Chinese Law Association

- The ADVN, as the first and largest anti-domestic violence organization in China, is responsible for significant progress in…

- Legislation

- Prosecution of crimes

- Social support

- Public awareness

- All of the above

- Which statement does NOT reflect the relationship between the ADVN and the Chinese government?

- Through the Chinese Law Association, the ADVN has ready access to government branches

- ADVN, like all NGOs in China, are strictly regulated by the government’s civil affairs office

- ADVN uses confrontational and radical strategies to pursue immediate and drastic policy changes

- ADVN uses non-confrontational ways of persuading male officials to accept their ideas

- All of the above

- According to the chapter, changing legislation…

- Takes time and requires extra resources to implement legislative changes

- Happens quickly

- Does not require a conciliatory relationship with government

- Is not resource intensive

- None of the above

- ADVN’s long-time sponsors do NOT include…

- Ford Foundation

- Swedish International Development Agency (SIDA)

- Oxfam Novib

- Open Society Foundations

- Human Rights Centre at the University of Norway

Answers

- The correct answer is one out of three (answer C).

- The correct answer is E. Restrictions on women for owning and inheriting property (answer C) and socially regulating women to the home (answer D) increase a society’s level of violence against women.

- The correct answer is intimate partner violence and sexual violence (answer D). Psychological violence and physical violence (answer A) are both named as types of intimate partner violence. Non-sexual violence (answer B) is not a category mentioned in the book. Structural violence and systemic violence (answer C) refer to institutionalized patterns of discrimination within society, but are not mentioned in the chapter.

- The correct answer is all of the above (answer D).

- The correct answer is North America (answer D). The textbook does discuss instances of violence against women in Africa (answer A), South and Central Asia (answer B) and the Middle East (answer C). North America is mentioned in two contexts: the assertion that women in the U.S. can escape domestic violence through social programs, and the location of honor killings in immigrant communities.

- The correct answer is all of the above (answer E).

- The correct answer is the sale of daughters by parents into forced labour for remittances (answer C). The chapter does not discuss forced deportations (answer A), detention of women and children by state bodies (answer B) or restrictive temporary foreign worker visas (answer D). These forms of trafficking are discussed in the external source from the Global Alliance against Trafficking in Women.

- The correct answer is women and girls (answer B). The chapter does not mention that trafficking can include women, men, and children of any gender (answer A) or migrant workers in exploitative situations (answer C).

- The correct answer is the Association des Femmes des Médias de Sud Kivu (AFEM) (answer B). Radio Maendeleo (answer A) is the radio station where Chouchou Namegabe began her career. South Kivu Province (answer D) is the province where she lives and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (answer C) is the country.

- The correct answer is that AFEM encourages women to break their silence and speak about their experience (answer A).

- Both answers A and B are correct. The AFEM program led to women becoming more comfortable discussing sexualized violence, and taboos around talking about sex in general are also weakening.

- The correct answer is the process of population removal to access Congolese minerals (answer B). Patriarchy (answer A) is another underlying factor but not specific to the Congolese context; fear and shame (answer C), as well as the intentional spread of HIV were tactics used by militia groups (answer D).

- The correct answer is the Anti-Domestic Violence Network (ADVN) (answer D). The China Law Society (answer A) is another NGO within the political system. The Chinese Law Association (answer E) is the umbrella organization, of which the ADVN is a member. The Marriage Law Association (answer D) is another agency within the Chinese Law Association, separate from the ADVN. The Modern Media Group (answer C) is the firm where Qin Liwen, one of the chapter’s authors, formerly worked.

- The correct answer is all of the above (answer E).

- The correct answer is C. The ADVN does NOT use confrontational or radical strategies in their advocacy work. The ADVN has ready access to government branches (answer A), is strictly regulated by the civil affairs office (answer B), and uses non-confrontational ways of persuading officials to accept their ideas (answer D).

- The correct answer is A. The chapter explains that changing legislation is time-intensive and organizations require additional resources to urge the implementation of new laws.

- The correct answer is D. Open Society Foundations is not a sponsor of ADVN.

Discussion Questions

- To what extent is violence towards women a “cultural” problem? Explain using examples from the chapter and other resources.

- What instances of violence against women are prevalent in your own community?

- Namegabe discusses the use of rape as a systemic weapon of war and population displacement. What are the economic activities surrounding these conflicts, and how do they link to international supply chains?

- What is the relationship between the “local” and the “global” in terms of activism and violence against women?

- How does the work of the ADVN relate to the Beijing Platform for Action?

- What does Chouchou Namegabe’s involvement with AFEM demonstrate about the power of women in the global South to address gender-based violence?

Essay Questions

- The chapter mentioned that ADVN’s sponsors, including the Ford Foundation, SIDA and Oxfam, began changing their sponsorship levels, so ADVN needed to learn how to raise funds for its own projects – and that it is doing so. How would an NGO go about raising funds? What challenges would this place on the organization’s advocacy work?

- As an NGO, the ADVN is tightly regulated by China’s civil affairs office and remains highly connected with government. How can a close relationship with government be a benefit and a hindrance to the advocacy work of an NGO? Does this depend on the political climate of the country in which the NGO operates?

- Page 56 discusses “trafficking” as a form of violence against women. Drawing from the additional learning resources below on the Global Alliance against Trafficking in Women, what is trafficking and what are some of its root causes? Is there anything problematic about the trafficking framework?

Additional Resources

Alwis, R. & Klugman, J. “Freedom From Violence and the Law: A Global Perspective in Light of Chinese Domestic Violence Law, 2015. University of Pennsylvania Journal of International Law 37(1): (2015).

Reviews the draft Chinese Domestic Violence Law and its relationship to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) agenda.

http://scholarship.law.upenn.edu/jil/vol37/iss1/2

Amnesty International. “No More Stolen Sisters.”

Amnesty International’s campaign with key statistics, information, and analysis relating to missing and murdered indigenous women in Canada.

http://www.amnesty.ca/our-work/campaigns/no-more-stolen-sisters

Borrows, J. “Aboriginal and Treaty Rights and Violence Against Women.” Osgoode Hall Law Journal 50(3): (2013), 699 – 736.

Suggests that section 35 of the Constitution can play a role in ensuring that different levels of government are responsible for addressing violence against women.

http://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1021&context=ohlj

Coker, D. “Domestic Violence and Social Justice: A Structural Intersectional Framework for Teaching About Domestic Violence.” Violence Against Women 22(12) 1426 – 1437: (2016).

Describes a course that challenges the neoliberal idea of individual responsibility in the context of abuse.

http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/1077801215625851

Everyday Feminism.

An educational platform working to deconstruct everyday violence, discrimination and marginalization by hosting discussion pieces on intersectional feminism.

Global Alliance against Trafficking in Women (GAATW).

A network of non-governmental organizations (NGOs) that work from a rights-based perspective to address the diverse issues that rise from trafficking-in-persons, including forced labour within the informal and formal economies.

Hayes, R. M., Abbott, R. L., & Cook, S. “It’s Her Fault: Student Acceptance of Rape Myths on Two College Campuses.” Violence Against Women 22(13): 1540 – 1555 (2016).

Examines factors that lead to acceptance of rape myths on two college campuses in the USA.

http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/1077801216630147

National Association of Friendship Centres. “Action for Indigenous Women.”

Contains information and resources to engage individuals, families, and communities to work together to end violence.

http://nafc.ca/en/action-for-indigenous-women/

TEDXABQ Women. “Violence against Aboriginal Women is not Traditional.” (2013).

A slam poem about the legacies of colonialism and impacts on violence against Indigenous women in the United States.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Mg2Jjam0p-U

The World’s Women 2015. “Violence Against Women.”

Annually updated data and analysis on violence against women in its physical, sexual, psychological and economic forms.

http://unstats.un.org/unsd/gender/chapter6/chapter6.html

True, J. “The Political Economy of Violence Against Women in Africa.” Open Society Initiative for Southern Africa. (2015).

Argues that the impacts of violence against women in Africa remain hidden due to notions of privacy, acceptance as a cultural norm, and insufficient institutional responses.

http://www.osisa.org/buwa/regional/political-economy-violence-against-women-africa