3 The Web Content Accessibility Guidelines

In this section, you will learn

- The four layers of the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG)

- Limitations of WCAG

- What is beyond the boundaries of WCAG

- See a demonstration of a screen reader interacting with a webpage

Framing Story: Preparing for university

Our space odyssey continues as the young astronaut worked their way through high school. Obstacles in sciences classes presented themselves again. But again, they found some educators who collaborated to creatively improve the situation.

They were following the footsteps of others, big and small, from near and far. An example of these footsteps was a 2009 conference in Iowa, where high school educators, assistive technology specialists, post-secondary educators, students with disabilities in high school and university, engineering students, as well as future teachers convened to discuss the accessibility of STEM education and careers[1] .

Years after the conference ended, with a bit of encouragement from their mom, the future astronaut enrolled again in the CNIB Learning Academy. This time it was the SCORE Scholar program. During this in-person summer program, they spent time with blind peers and blind instructors who taught them skills to help the transition to university or college.

One evening, their young mind returned to the dream of being an astronaut and they return to the Canadian Space Agency’s webpage about Jeremy Hansen’s mission patch. Although well designed in many ways, the teen noticed obstacles.

But they also found hope. Because, you see, filled with curiosity about space and the Seven Sacred Laws depicted in the patch, they wondered: “How big is a buffalo?” and “Do eagles make sounds when they fly?”

WCAG Overview

The World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) is an international standards organization that develops technical guidelines. In 2008 the W3C published and endorsed the WCAG 2.0 (version WCAG 2.1 and WCAG 2.2 have also been published). The guidelines are essentially usability guidelines that provide reminders to include features needed to make web content usable by people with disabilities.

The guidelines are meant to be technologically agnostic. This means they could be applied to any type of web content, such as HTML or PDF. (At one point, the WCAG authors recognized Flash and Silverlight, which are now discontinued web technologies). Since web developers are a key audience, the guidelines have a very formal and technical tone. However, in recent years, the W3C has published more non-technical supplementary material and provided resources for a wider spectrum of roles.

We can think of the guidelines like a layered cake. Each layer supports the one above it. The top layer (Layer 1) is the most abstract and the bottom layer the most technical.

Layer 1: Principles

The WCAG guidelines are essentially usability guidelines structured around four principles. To be usable by anyone, content must be:

- Perceivable. If a person can’t perceive content, then it’s not usable

- Operable: If a person can’t operate the content, then its not usable

- Understandable: If a person can’t understand the content, then it’s not usable

- Robust: Content should be compatible with a variety of browsers and assistive technologies. If a web page only worked with one browser, would you consider it usable?

Layer 2: Guidelines

Each principle is supported by a number of abstract guidelines. Guidelines help make the principles a reality. For example, the principle of “perceivability” has four abstract guidelines:

- 1.1 Text alternative

- 1.2 Time-based media

- 1.3 Adaptable

- 1.4 Distinguishable

Let’s examine one of the guidelines more closely. Guideline 1.3 is about creating content that is adaptable. It states, “create content that can be presented in different ways (for example simpler layout) without losing information or structure.” This means we should not assume that content will be presented in one way (e.g., on a laptop screen). It should be made flexible so it can be presented on a big screen, a small screen, in sound, or through a tactile display.

At this point, this is just abstract guidance. While the practical “how-to” comes at lower levels, becoming fluent in “why we do things” can be as helpful as “how we do things.”

Layer 3. Success Criteria

For each guideline, WCAG defines a number of success criteria. These criteria must be met if the content is to be successful in following the guidelines. For example, Guideline 1.3 Adaptable has three success criteria:

1.3.1 Info and Relationships: Information, structure, and relationships conveyed through presentation can be programmatically determined or are available in text.

1.3.2 Meaningful Sequence: When the sequence in which content is presented affects its meaning, a correct reading sequence can be programmatically determined.

1.3.3 Sensory Characteristics: Instructions provided for understanding and operating content do not rely solely on sensory characteristics of components such as shape, size, visual location, orientation, or sound.

At this layer, the language becomes more precise because success criteria are designed to be testable. If a test for a success criterion fails, then the guideline is not being followed. When these “failures” happen, they tell us we are off track – we are not following a guideline – and need to include a feature that some people will need.

Layer 4. Techniques and tests

The final layer is the most technical. The authors of WCAG also published specific authoring or coding techniques to meet the success criteria. They also provided some tests to determine if success criteria are broken.

But these techniques and tests aren’t exhaustive. It’s like a mother creating a binder of family favourite meals for a grown child that is moving out of the home. The binder doesn’t contain recipes for every situation that will present itself. The young adult has a responsibility to add recipes to the binder too.

Limitations of WCAG

There are at least three limitations of WCAG. First, WCAG doesn’t tell us what content people with disabilities may want or value. For example, when Ashley was the Laurier Library Web Accessibility Advisor, she drew the web team’s attention to a problem: blind people may not know why they should bother coming into the library – “Isn’t it a giant building filled with print books on bookshelves?” Since a library is more than this, she advised describing the library space, what goes on in the library, and how to access it. Image 6 shows a series of images and descriptions for entering the library.

The Laurier Library has pages with description and images for each floor of the Waterloo campus library. If blind members of the community want support from sighted people (e.g., sighted orientation and mobility specialists, friends), the images are available (each image has alternative text). The images also support anyone with a disability who wants to know if the library has features they need[2]. What’s important to note is that WCAG didn’t guide the library to producing these pages. It was having Ashley, a member of the community the library wanted to serve better, on the library web team who focused the team on the missing content.

A second limitation of WCAG is that it does not recognize all obstacles. WCAG’s introduction says: “Although these guidelines cover a wide range of issues, they are not able to address the needs of people with all types, degrees, and combinations of disability”[3]. People with both vision and learning disabilities may require formats and technologies which conflict with one another until new solutions are found. As people with disabilities and disability groups draw attention to obstacles and what works, and as research is done to learn more (e.g., Cognitive Accessibility User Research), the W3C evolves the guidelines. For example, WCAG 2.0 was initially published in 2008, then WCAG 2.1 in 2018, and WCAG 2.2 in 2023. With each update, more obstacles were addressed.

A third limitation of WCAG is probably common to other guidelines. They lend themselves to some people insisting that all they have to do is “meet the guidelines.” The guidelines are treated as a kind of “finish line.” However, the Charter of Rights and Freedoms require us to remove disadvantages up to the point of undue hardship. We have to recognize and respond to obstacles beyond WCAG.

What is beyond WCAG?

While compliance with WCAG is incredibly important, they do not define the horizon in which burdens or disadvantages are to be recognized. Disadvantage can appear because of a variety of factors, such as:

- Economic factors: is there funding for assistive technologies or does a particular social group need to rely on free or low-cost options?

- Linguistic/cultural factors: Which languages are supported by which screen readers? Some languages have braille codes and others do not.

- Environmental factors: Do particular assistive technologies tend to be used on a particular campus? Within a particular field or discipline?

While these factors may be shared societally, educational environments are still expected to respond to disadvantages. For example, perhaps post-secondary libraries could support assistive technology collections, like the one created by the Assistive Technology Loan Program offered through the Center for Inclusive Design and Innovation at the Georgia Institute of Technology? Or perhaps libraries could reach out to Braille Literacy Canada to speak about the development of the Mi’kmaw braille code?

Compliance with WCAG is therefore just the baseline – a starting point that gives us reminders to include features that address the needs of some disabilities. It is not an endpoint. Wherever disadvantages appear, no matter how big or small, creative and collaborative responses are still called for.

So, let’s see if we can find some examples of issues beyond WCAG.

Demo: Canadian Space Agency, Part 2

Let’s take a closer look at the example from the Canadian Space Agency.

The demo shows that the player is presenting problems. The visual representation of the player is very clean and clear (see Image 7).

But what is it like in an aural interface? When stepping through the video player in the Edge browser (version 122) and JAWS 2024 (with low verbosity settings), this is the aural experience:

- Jeremy Hansen’s mission patch: recognizing Indigenous Peoples, Button, Play

- Jeremy Hansen’s mission patch: recognizing Indigenous Peoples, Toggle button, Mute

- Jeremy Hansen’s mission patch: recognizing Indigenous Peoples, Left right slider, 100 Volume min 0 max 100

- Progress bar, 0 percent

- Jeremy Hansen’s mission patch: recognizing Indigenous Peoples, Toggle button, Show closed captioning

- Jeremy Hansen’s mission patch: recognizing Indigenous Peoples, Toggle button, Enter full screen

Notice how “Jeremy Hansen’s mission patch: recognizing Indigenous Peoples” is part of every button in the controller. This creates excessive cognitive load for the user experience. It makes it difficult to perceive and operate the video player controllers. This issue can probably be fixed quite easily by the Canadian Space Agency.

There’s a second issue. Notice how the video player is the most prominent part of the visual interface. The player’s size, position, and preview image focuses visual attention immediately and guides sighted users to play the video.

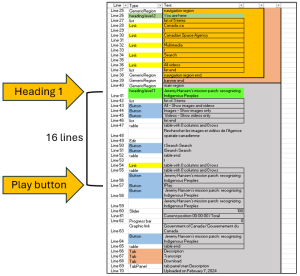

However, if we examine the structure of the aural interface (see Image 9), we see a significant difference. How would a person know there is a video player on the page? The title of the page also gives no indication of that. And the heading 1, which is perhaps the most prominent feature when navigating with screen readers, is 16 steps away from the play button. And between the heading 1 and the play button are three buttons labelled All, Images, and Video, an edit box for searching, and a search button. Could a user be faulted if they arrived at the heading 1 and, after a bit of exploring, they missed the play button?

So, while the Canadian Space Agency’s webpage may be technically well built, we can’t be so wedded to WCAG that they prevent us from recognizing other disadvantages in how the page is created.

But there are other issues beyond WCAG. While sighted users get a deeply engaging experience through the visual aspects of the video, blind users are disadvantaged because the Canadian Space Agency relies so heavily on visual information. But couldn’t the Canadian Space Agency offer tactile representations of the patch? The Chandra X-ray Center, which is operated for NASA by the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory offers a wealth of educational resources for “Universe of Touch and Sound”, including lots of sonifications of astrophysical data and a Touchable Universe in a Box (see Image 10).

Surely the Canadian Space Agency can be as creative when engaging with blind learners[4]!

They will have to be because, as you know, there is a young blind person determined to be an astronaut!

- Rule, A., C., Stefanich, G. P., Haselhuhn, C. W., & Peiffer, B. (2009). A Working Conference on Students with Disabilities in STEM Coursework and Careers. ↵

- At a presentation hosted by the International Association of Researchers with Vision Loss and their Allies, Dr. Theresa Edelman also explained the benefits of proactively describing spaces for people with non-visual disabilities. ↵

- Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2.0 ↵

- Mark reached out to the Canadian Space Agency to talk about accessibility issues with their page. ↵