2 About screen readers

In this section, you will learn

- What screen readers are and how they work

- Some myths and facts about screen readers and their use

- How blind people typically learn to use screen readers

- Methods sighted people can use to learn screen readers

- What a screen reader looks and sounds like in action

Framing Story: In high school, basics of screen reader and websites

In our story, the future astronaut is now in elementary school. Like others their age, they took a keen interest in technology. In particular, the intricacies of screen readers, braille notetakers, and braille displays captured this young astronaut’s imagination.

Through monthly meetings hosted by the CNIB and Ontario Parents of Visually Impaired Children (OPVIC), the youngster’s mom learned about the CNIB Learning Academy.

Dreams of becoming an astronaut were fueled after the student watched Wanda Diaz Merced’s talk How a blind astronomer found a way to hear the stars.

Their commitment to become an astronaut deepened after learning about AstroAccess. This initiative aimed to make outer space accessible for people with disabilities. Among the blind on microgravity missions were Dr. Mona Minkara, Azubuiki Onwuta, Dr. Sheri Wells-Jensen, Sina Bahram, and Lindsay Yazzolino.

Because of these role models, the student became active in every class, club, or activity related to science, math, engineering, or technology (STEM).

It was challenging at times. STEM materials weren’t too accessible. But what was exciting was when the student and their teachers worked together to come up with creative, alternate ways of learning and involving the student in activities.

For a class project, the future astronaut visited the Canadian Space Agency’s website. Because of blind advocates, such as Donna Jodhan, government of Canada websites were far more accessible than before.

And it was here where they found a page about Jeremy Hansen’s mission patch.

What are screen readers?

Screen readers turn digital text into synthesized speech. They can also turn digital text into braille that can be read using a refreshable braille display (see Image 1). With a braille display, there is no need for a monitor! A tactile interface is conveyed through the braille cells! In fact, many braille readers will pair their braille display with their phone in their pocket or laptop on another table because they have no need for screens.

Screen readers also enable users to navigate web and software interfaces using the keyboard, even in many situations where sighted users would navigate using a mouse. The screen reading software essentially mediates between the user and the mainstream webpage or software applications being used. Because of this, a user of a screen reader may go about tasks in a different way than sighted users do. Also, the screen reader may alter output from some software so that the content can be better conveyed through non-visual means.

Different screen readers work with different operating systems, and each have their own distinct sets of commands and features. Examples include:

- Windows: Narrator, Job Access with Speech (JAWS), Non-Visual Desktop Access (NVDA)

- MacOS: VoiceOver

- iOS and iPad OS: VoiceOver

In some ways, screen readers are like musical instruments. If a person knows how to play a guitar it doesn’t mean they can jump right into playing a violin. Same with screen readers. If a person knows VoiceOver, it doesn’t mean they can just jump in and start using JAWS.

In this resource, we’ll be focusing on JAWS for Windows, which is commonly used in educational settings and workplaces around the world.

Myths and facts about blindness and screen readers

Myth 1: Blind people don’t use computers; a sighted person will be helping out.

Fact: When provided with the appropriate assistive technologies, and accessible software and content, blind people can use computers very effectively.

Myth 2: All you need is a copy of JAWS and everything will be fine.

Fact: The web content and software creators have to do some work to make content that will work with JAWS. This is part of what you owe to your users if you are involved in creating digital content.

Myth 3: A screen reader is literally reading the screen

Fact: If a person shares their screen in Zoom, another person’s screen reader won’t be able to interact with it. For technical readers, a screen reader is actually interacting with a digital representation of the user interface (the User Interface Automation tree) that resides in your computer’s main memory.

Myth 4: Using a screen reader is overwhelming. It talks so fast!

Fact: Using a screen reader is like playing a piano. It involves some theory and lots of practice. Just as an expert piano player can move exceptionally fast and hear meaningful sounds, so too can a screen reader user. When content is built well, it is lots of fun.

Myth 5: Everyone who uses JAWS or a screen reader is a super user.

Fact: People’s skills vary. Opportunities to access training can be unfairly distributed. Or people may still be learning non-visual skills.

Myth 6: Screen readers replace the need for braille

Fact: Braille is an essential literacy skill supporting spelling, grammar, music, additional language learning, and mathematical and science notation. The screen reader is an ally for braille, not a replacement.

How do people learn to use screen readers

Blind users and learning screen readers: Ashley’s thoughts

There are a wide range of ways blind students, researchers, or faculty may learn to use screen readers. Most screen reading software comes with user guides and tutorials that are text or audio-based. Training materials often feature audio of the trainer describing how to accomplish tasks, and include the screen reader’s text to speech output so the trainee can follow along. Think of this as the alternative to video instructions with screenshots used by sighted software trainees. For instance, the company that makes JAWS hosts a podcast called FSCast that includes all sorts of demonstrations, as well as on demand webinars. New users can work through this type of content themselves, or may be supported by specialized assistive technology trainers.

Experiences and proficiency with screen readers are impacted by a number of factors including:

- Age of disability onset

- Degree of vision loss

- Presence of additional disabilities

- Access to vision rehabilitation strategies and skills, which include learning strategies and technology training

Other variables that can have an impact include:

- Level of education

- Economic factors

- The person’s attitudes, and the attitudes of those around them

- Access to role models

Examples

Example 1: A totally blind person working as a university statistics professor in a psychology department. They have been blind since birth and learned to use screen readers and other assistive technologies as a child. Their early training was provided by specialized assistive technology instructors, until they had a sufficient level of skill to begin teaching themselves through independent discovery and connecting with other advanced users. They would currently be considered an advanced screen reader user

Example 2: A political science post-doctoral researcher, who began to lose their vision as a teenager. Their vision has gradually deteriorated over time. They used screen magnification software throughout most of their post-secondary education, until their vision became too low to read magnified text. They began to receive specialized training to use a screen reader while working on their doctoral dissertation, but have found navigating using the keyboard and listening to text to speech rather than reading visually to be challenging. It has also been challenging for them to keep up with their current workload while learning a whole new way of using the computer. They would currently be considered a beginner to intermediate screen reader user.

Think about the differences between the backgrounds and experiences of these two users. Just like sighted computer users, blind screen reader users have varying levels of skill, aptitude, and interest in technology.

Sighted users and learning screen readers: Mark’s thoughts

When hearing a screen reader for the first time, sighted people can be either overwhelmed or awestruck. In her research, Dr. Arielle Silverman found that when people are “shocked” by brief immersions into experiences without their sight, it can reinforce negative stereotypes about blindness[1].

To avoid this problem, it might be helpful to think of learning to use a screen reader as like learning to play the piano. When we learn to play a piano, we don’t just sit down at the keys and suddenly play music. It takes effort to learn some theory and time to develop new skills. The same is true when becoming skilled with a screen reader. It’s a matter of learning new ideas and developing non-visual skills.

Even with this analogy, sighted people may become confused when finding their learning environment does not meet their expectations. So, what do you do when confused by your learning environment? You adapt or create things to make your environment more supportive! For example, if you are not used to reaching certain specialized keyboard commands used by JAWS, you can add a few textures to a keyboard to make it easier. We all need training wheels at some point!

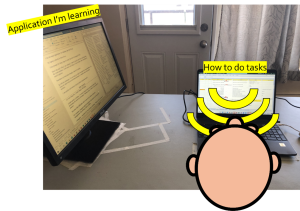

Another simple adaptation to develop non-visual skills involves two monitors. On the screen in front of you, put reminders of shortcut keys for an application. On a second monitor, put the application you are using with JAWS. Position it perpendicular to the first so you can’t see it unless you turn your head (see Image 2). If you find yourself wanting to turn your head to the side monitor, then you got a clear signal more learning or practice is needed!

Image 2. Two-monitor setup for developing JAWS listening skills

It’s also helpful to invest time to develop conceptual knowledge about the aural interface. Sighted people have so many ideas rooted in the visual interface that it can be hard to let them go. However, having conceptual knowledge about the aural interface can make it easier. In the current landscape, it is hard to find learning materials to support this conceptual development. Reading technical material, not intended for learning screen readers can be helpful. For example, the World Wide Web consortium publishes technical descriptions of accessible user interface components. While intended for web developers, it can also be helpful when learning how to interact with user interface components. For example, the description of the Tree View, provides terminology, describes recommended keyboard commands, and provides examples.

Hiring a JAWS instructor can be very helpful. One-on-one conversations can be very helpful for clearing up misconceptions quickly. For example, Mark’s instructor, Meared, was able to address questions that were really confusing him.

It is also helpful to have role models of what is possible with non-visual skills and computers. Both Meared and Ashley would stretch Mark’s imagination about what was possible! It’s like starting out learning to play a guitar and watching Eddie Van Halen do a guitar solo! “I didn’t know people could do that! That’s so cool!”. Dr. Arielle Silverman has also written that blind role models may have a positive impact on sighted people’s attitudes about blindness[2].

As a sighted person, learning a screen reader comes with other responsibilities.

- Report problems when you find them

- Get involved in blind communities to learn about obstacles and the joys of blindness

- Be humble

Demo: Canadian Space Agency, Part 1

Let’s see a screen reader in action! We’ll start with a basic navigation of the page with regions, headings, buttons etc.

Mapping the JAWS aural interface

To appreciate the JAWS aural interface, we can visualize it using a technique we refer to as creating a “JAWS map”. First, lets see the visual interface of the Canadian Space Agency’s webpage (see Image 3).

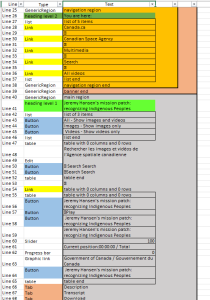

From a sighted perspective, the visual interface page is quite well designed. We can also examine the aural interface. To help with this, image 4 shows a visualization of the aural interface that JAWS constructs in sound. A JAWS map is built by going to the top of the page and pressing the down key which makes JAWS speak a line of the interface[3]. Each JAWS utterance is then broken down into its components and recorded in a row in a table. The first column, which is not spoken, is just the line number in the aural interface. The second column is the control type, like heading, link, or button. The third column is the label. Colour schemes are then used to indicate if an item is a button, link, or heading, and if items are part of the same HTML region.

Image 5 shows the relationship between the visual and aural interfaces. We can see how parts of the visual interface correspond to parts of the aural interface, such as the heading level 1, the play button, and the description tab.

One thing to notice is that the visual interface is a 2-dimensional structure, while the aural interface is more linear in nature. This is why we shouldn’t give instructions to users like “click the button in the top right corner”. There are no corners in a linear structure! It’s better to include the label in instructions, like “click the button labelled Submit in the top right corner”, which will work for users of both interfaces.

- Silverman, A. M. (2015). The perils of playing blind: Problems with blindness simulation and a better way to teach about blindness. Journal of Blindness Innovation and Research, 5(2). ↵

- Silverman, A. (2017 June). Disability Simulations: What Does the Research Say? Braille Monitor. ↵

- The map was constructed with the support of a script developed for Mark by Udo Egner-Walter. ↵