A Note to Readers

Reflections of a MCMASTER Instructor

By Michael Wong, PhD

The COVID-19 pandemic was not easy on education. It challenged teaching and learning in unprecedented ways and forced many educators to adapt face-to-face classes for remote instruction. Despite these challenges, the COVID-19 pandemic was filled with learning and reflection in higher education. Teaching during the pandemic challenged me, and likely many others, to think beyond the traditional space-time boundaries of education. As stressful as the transition from face-to-face to remote delivery was, there was a beauty in removing those physical boundaries. With lockdowns and restrictions across the globe, many of us were communicating almost exclusively using teleconferencing software such as Zoom or Microsoft Teams. Communicating with someone locally did not feel so different from communicating with someone from the other side of the world. In fact, in my own classes, I had students who were “Zooming” in from different countries, including the United States, the United Kingdom, South Korea, and China. If they had not told me, I would have no idea they were not located within Southern Ontario!

The COVID-19 pandemic was not easy on education. It challenged teaching and learning in unprecedented ways and forced many educators to adapt face-to-face classes for remote instruction. Despite these challenges, the COVID-19 pandemic was filled with learning and reflection in higher education. Teaching during the pandemic challenged me, and likely many others, to think beyond the traditional space-time boundaries of education. As stressful as the transition from face-to-face to remote delivery was, there was a beauty in removing those physical boundaries. With lockdowns and restrictions across the globe, many of us were communicating almost exclusively using teleconferencing software such as Zoom or Microsoft Teams. Communicating with someone locally did not feel so different from communicating with someone from the other side of the world. In fact, in my own classes, I had students who were “Zooming” in from different countries, including the United States, the United Kingdom, South Korea, and China. If they had not told me, I would have no idea they were not located within Southern Ontario!

This experience gave me the realization that higher education could leverage teleconferencing technologies to be connected globally. This would provide students the opportunity to work with and learn from others around the world. With this in mind, I began to explore ways in which I could bring a global experience into my classroom. At first, I was thinking about inviting guest speakers from different parts of the world into my classes, which I did, but I also began to explore different possibilities that would enable my students to learn from and collaborate with students from a completely different culture. In an increasingly globalized world, there is much value in learning how to work with people with different ways of knowing, thinking, values, and perspectives. I stumbled across an advertisement on the website of the Office of International Affairs about Virtual Exchange. I was connected with Paul Leegsma, who described the Virtual Exchange process to me. Although I was intrigued, I did not know what to expect. Paul later connected me with a possible Virtual Exchange partner, Nergiz Turgut, a professor at USFQ in Ecuador. It was this conversation that led me to truly see the benefits of a Virtual Exchange collaboration. Even in that short meeting, I learned a bit about Ecuadorian culture and differences between our pedagogies. If I learned so much in a brief conversation, I began to anticipate how much my students would learn in a one-semester project. Shortly after that meeting, our collaboration began. We spent the latter half of the Fall 2021 semester preparing for our collaboration in the Winter 2022 semester. We paired level 3 health sciences students at McMaster University in a Neuroplasticity Inquiry Course with level 3 psychology students at USFQ. Ultimately, we decided our students would learn most if they worked closely with one another, rather than from didactic lectures given by the professors. We implemented an inquiry-based project that challenged students to (1) identify an issue in neuroscience and (2) generate an intervention. This particular collaboration was highly notable as it was one of few Virtual Exchange projects at the undergraduate level at McMaster University and globally in STEM education (specifically using an inquiry and problem-based approach).

An important component of this Virtual Exchange project required regular written reflections from students about the development of their inter-cultural and interdisciplinary skills. The final output was a “Shark-Tank” style pitch presentation where students presented their interventions to a panel of external guests who have worked in various sectors, including healthcare, psychology, neuroscience, and business. We have had guest judges from different regions of the world including, North America, South America, Europe, and Asia. This Virtual Exchange project provided McMaster University students an alternative to study-abroad programs that would have otherwise only been available to a few students due to factors such as travel expenses. By using virtual tools and innovative online pedagogies, this course-embedded Virtual Exchange was able to connect two classes from different parts of the world in an environment where students could collaborate, interact and take ownership of their education, while expanding their intercultural and interdisciplinary learning.

Our collaboration was a highly enjoyable and fruitful one. It was so enjoyable that we have continued to collaborate on Virtual Exchanges each subsequent semester, and we anticipate continuing our partnership in the foreseeable future! For this reason, we decided to develop a guide for individuals at McMaster University, who might also be interested in implementing a Virtual Exchange into their own curricula and courses. Although other Virtual Exchanges have been conducted at McMaster University (e.g., McMaster Global Health Program), our guide focuses specifically on a course-embedded Virtual Exchange at the undergraduate level. We hope this guide will provide you with the necessary information to get started in your own Virtual Exchange. We will provide an overview of what to expect, what needs to be done, and what challenges to anticipate.

REFLECTIONS OF A Mcmaster MANAGER FOR GLOBAL STRATEGIC ENGAGEMENT

By Paul Leegsma

I first heard the terms “COIL” and “Virtual Exchange” in early 2020 as the implications of the COVID-19 pandemic for international education were making themselves felt. I was immediately struck that this seemed like one of few silver linings in a juncture of profound uncertainty. As professors shifted to online instruction, in terms of internationalization goals (my wheelhouse), COIL/VE also had the advantage of appearing as a readily doable, even organic, extension of the instructional modalities everyone was rushing to use. From my perspective, COIL/VE presented an opportunity to fulfil an agenda to achieve “internationalization-at-home” both meaningfully and with the potential to do so at scale. Further, the exigencies of the moment for universities gave energy to this whole other way to engage a breadth of students in a way that would also exactly help address common barriers to student participation in physical exchange: it mitigated issues of cost, travel anxiety, accessibility, and even the common frames of reference that make the traditional exchange experience seem impractical or irrelevant to their academic and career goals.

I first heard the terms “COIL” and “Virtual Exchange” in early 2020 as the implications of the COVID-19 pandemic for international education were making themselves felt. I was immediately struck that this seemed like one of few silver linings in a juncture of profound uncertainty. As professors shifted to online instruction, in terms of internationalization goals (my wheelhouse), COIL/VE also had the advantage of appearing as a readily doable, even organic, extension of the instructional modalities everyone was rushing to use. From my perspective, COIL/VE presented an opportunity to fulfil an agenda to achieve “internationalization-at-home” both meaningfully and with the potential to do so at scale. Further, the exigencies of the moment for universities gave energy to this whole other way to engage a breadth of students in a way that would also exactly help address common barriers to student participation in physical exchange: it mitigated issues of cost, travel anxiety, accessibility, and even the common frames of reference that make the traditional exchange experience seem impractical or irrelevant to their academic and career goals.

We developed this guide with the understanding that COIL/VE implementation presents an additional workload for already overloaded faculty. The goal then was to document the process in a way that minimizes the implementation workload and will make it as frictionless as possible, ie., helping faculty to understand that they can scale their COIL/VE activity to fit within shorter timeframes and current curriculum requirements, and, that interested senior level students can be engaged as part of their research and learning development to support the implementation process – and make the experience all the more engaging for the participating students.

From the institutional perspective, COIL/VE has become an essential part of an institutional tool belt of approaches to Transnational Education and one that, from this perspective, provides a low-resource, low-risk foothold for other modes of engagement between international collaborators. Our hope is that this guide helps COIL/VE practices spread more widely across the university.

On a personal level, it has been really amazing to meet and work with Mike Wong on the McMaster side and Nergiz Turgut and Sol Garcés Espinosa on the USFQ side. From the McMaster perspective, I can’t imagine a better faculty champion for COIL/VE in terms of instruction and pedagogy. Mike has brought “three C’s” at all times to his approach that has helped the program to continually improve and innovate: conscientiousness, creativity and compassion – and this level of commitment and engagement has been mirrored on the USFQ side by both Nergiz and Sol. Thanks to all of their advocacy and consideration, this program has also been blessed by the involvement of outstanding student coordinators and researchers who, among making many other valuable contributions, were instrumental in making this guide come together. Especially in this regard, Shaaf Farooq and Hasan Ahmad worked tirelessly through many, many iterative cycles over years as this guide came together.

As a parting reflection, I observe how quickly since 2020 fully online instruction has become standard. The before-time of strictly in-person instruction has become nearly unthinkable. While having an appreciation of this not as an entirely positive development, the sense of the inevitable momentum towards increasingly broader bandwidth available for more immersive virtual collaboration is difficult to escape. In my view, we should continue to maximise in-person educational experiences (both at home and in international mobility), however, the quality of the solution that COIL presents as the supporting technologies evolve, also means that where the virtual exchange modality is optimal and desirable, it will become a more and more compelling and effective educational experience in itself, crucially both in terms of the subject learning dynamics as well as elements of inter-cultural communication. In 2025, as the dynamics of global engagement are experiencing profound turbulence, it is vital that we not lose sight of the benefits of COIL/VE as an impactful exercise in bridge-building for students, faculty and institutions.

Reflections of a usfq instructor

By Nergiz Turgut, PhD

Many people assume that online teaching or virtual classes lack engagement, but I would strongly disagree. In my experience as a full-time professor working on campus at Universidad San Francisco de Quito and currently teaching virtually from Belgium, I can say that they open up a world of possibilities, allowing classrooms to connect globally. Over the years, I have found that watching students from different cultural backgrounds collaborate, learn from each other, and build lasting friendships has been one of the most rewarding aspects of my work as a teacher.

Many people assume that online teaching or virtual classes lack engagement, but I would strongly disagree. In my experience as a full-time professor working on campus at Universidad San Francisco de Quito and currently teaching virtually from Belgium, I can say that they open up a world of possibilities, allowing classrooms to connect globally. Over the years, I have found that watching students from different cultural backgrounds collaborate, learn from each other, and build lasting friendships has been one of the most rewarding aspects of my work as a teacher.

Each class and project presents its own unique challenges, even when the tasks are similar. Navigating differences in timing, time zones, communication styles, and student confidence levels requires flexibility and adaptability. Supervising these groups is always a highly personalized experience—challenging at times, but incredibly fulfilling. It is inspiring to see students grow, overcome insecurities, gain confidence, and form meaningful connections. The initial hesitation quickly turns into curiosity, and before long, they are actively engaging in discussions and challenging each other’s perspectives.

Throughout the years, I have learned so much—not only from the students but also from my colleagues. Working with Mike and Paul has taught me valuable lessons about teaching strategies, language, communication, and culture. When I had the opportunity to visit McMaster University in person, I was warmly welcomed and deeply impressed by both the faculty and students. Their adaptability, creativity, and openness to learning have been truly inspiring.

The exchange of knowledge is not just about academic content—it is about perspective, cultural awareness, and the realization that, despite our differences, we share common goals and aspirations. Finding connections in a virtual space has shown me that meaningful learning does not always require being in the same physical location. What truly matters is fostering an environment where curiosity thrives, ideas are challenged, and friendships are formed. My hope is that both students and professors continue to maintain these global connections and embrace opportunities that push them beyond their comfort zones.

Reflections of a MCMASTER Student

By Hasan Ahmad

The dawn of the pandemic presented a novel challenge to students. How could we possibly navigate a virtual space? Being sprung from a familiar classroom setting, navigated by generations prior, to an unexplored virtual space was hard. I could not fathom it, but it sparked a profound curiosity as to what the possibilities could be.

Before I could remember, I valued intercultural awareness and knowledge, deeply rooted in my upbringing in the Greater Toronto Area, widely known as the most multicultural city in the world. Growing up, I spent my leisure time learning the geography of different lands and the history of those lands, sprung from my encounters with a diversity of peoples, cultures, and languages outside. In high school, I took Spanish classes, alongside choosing to continue my French classes, to better understand and immerse myself with friends and locals, hailing from these diverse backgrounds.

Fast forward to my third year in the Health Sciences program, where I enrolled in Michael Wong’s HTHSCI 3E03 – Inquiry III: Advanced Inquiry in Health Sciences (Neuroplasticity). I initially came to learn neuroplasticity but quickly gained something more valuable. As we held class introductions, we came to learn that we had another set of classmates we had not encountered in the program before. I quickly regained focus and peered in to learn who else I would be working with. My classmates are from USFQ, a university in Ecuador. As I met these classmates, learned more about Ecuadorian culture, and built a relationship while finding innovative methods to address some of the largest neuro-related issues in healthcare, these encounters provided an enriched experience that felt missing in my time at McMaster. As we presented our idea: “Mind Up”, an elder-friendly application targeted at delaying cognitive decline in patients with neurodegenerative diseases, these unique interactions taught me how an all-encompassing international collaboration—bringing together multiple perspectives—could create ingenious solutions to current large-scale issues. The course not only became my favourite in the Health Sciences program, but Virtual Exchange became my favourite project in all of undergrad.

This guide presents a tangible method to capitalize on a unique opportunity for educators, instructors, and students to not only work collaboratively, but become leaders of a global age that requires a global effort to combat some of the largest issues humankind has ever faced.

Reflections of a USFQ Student and Student COOrindator

By Nathan A. Azuero Guijarro

“Another virtual class again?” Those were the first words that crossed my mind as I enrolled for Neuroscience and Behavior back in January 2023. The COVID-19 pandemic and its forceful switch to a virtual learning and teaching modality were definitely not easy for most people, especially for me. As somebody who enjoys actively participating in class, engaging in the professor’s dialogue, and who missed peer-to-peer interactions with my classmates, having another virtual class, despite the apparent soon end of the pandemic, felt as if this horrible virtual isolation would never end. I guessed that online learning would stay forever. Now I am so thankful that it did.

“Another virtual class again?” Those were the first words that crossed my mind as I enrolled for Neuroscience and Behavior back in January 2023. The COVID-19 pandemic and its forceful switch to a virtual learning and teaching modality were definitely not easy for most people, especially for me. As somebody who enjoys actively participating in class, engaging in the professor’s dialogue, and who missed peer-to-peer interactions with my classmates, having another virtual class, despite the apparent soon end of the pandemic, felt as if this horrible virtual isolation would never end. I guessed that online learning would stay forever. Now I am so thankful that it did.

“For this semester, I want to offer you this new opportunity: A Virtual Exchange with McMaster University in Canada” Dr. Nergiz Turgut said, as the first weeks of the semester passed by. It turned out that USFQ students could have the chance to work on a final project with students from a distant university in Canada, as if the two classes merged into one. The idea sounded very intriguing. I didn’t think twice and signed up for it.

I got paired up with an excellent team, from which I learned what teamwork, commitment, and the advantages of cultural exchange actually mean. Combining ideas that emerged from the minds of Ecuadorian and Canadian students and seeing that combination flow smoothly into a beautiful output felt so fulfilling to me. The different perspectives enriched our project in ways I hadn’t expected: Canadian students brought structured methodological approaches while we Ecuadorians contributed creative intervention applications relevant to diverse cultural contexts. Fast forward to the weeks before the final submission, and I was really happy with the intervention idea that my team came up with (and I guess the jury too, as we ended up being second runner-up!).

After that wonderful semester, I pleasantly accepted the opportunity to work with Nergiz as a TA for her Neuroscience and Behavior lecture. “Would you also like to collaborate as a Student Coordinator for the Virtual Exchange Project?” she asked. Considering how enjoyable working with a new culture had been, I couldn’t hold back and jumped into the Virtual Exchange team in August of 2023. This would result in a decision I would never regret.

As a Student Coordinator, my responsibilities evolved beyond my expectations. I attended weekly check-ins between international teams, troubleshooting communication challenges and technological barriers. I provided valuable insights to the Virtual Exchange team from the USFQ perspective, sharing feedback that helped refine and enhance the Virtual Exchange methodology. One of my most significant contributions was assisting in hosting the closing ceremony: The final event where all ten teams present their final intervention pitches to the jury. Watching students confidently present their collaborative work made every effort worthwhile. The most rewarding moments came when I witnessed students overcome their initial hesitation and develop genuine cross-cultural friendships that extended beyond the academic requirements.

Two years have passed since I joined the Virtual Exchange team. Those two years are full of enriching learnings, memorable moments, and lasting connections. One of the most rewarding aspects of being a Virtual Exchange Student Coordinator is simply watching students engage and get curious about getting in touch with new cultures. And I think Canada and Ecuador are just the best two places to establish such a multicultural exchange. Ecuador, known as the land of the four worlds, encapsulates many peoples, traditions, and identities in such a small area. Canada, on the other hand, has always welcomed nationalities from around the world. Such action constitutes one of its principal values as a nation.

Looking forward to the future, I’m confident in saying that this Virtual Exchange initiative is meant to endure. Nergiz and Mike have worked tirelessly and developed such an amazing project for students interested in Neuroscience and Neuroplasticity thanks to their professional leadership and management. From skeptical participant to passionate coordinator, my journey with Virtual Exchange has transformed not just my academic experience but my understanding of what education can achieve across borders. I am glad that this project remains in good hands!

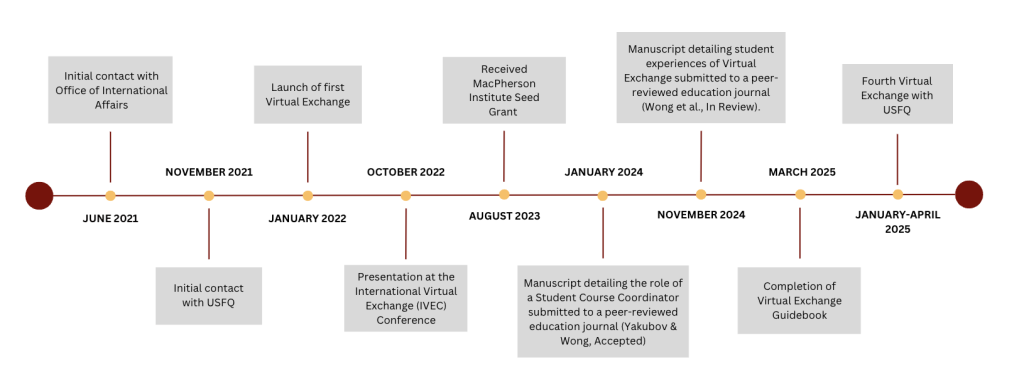

OUR JOURNEY

To capture our Virtual Exchange accomplishments, below is a timeline of major milestones up until the release of this guide (2025). Our initial contact with the Office of International Affairs at McMaster in June 2021 set the stage to connect with our partners at USFQ in November. As we began to hold discussions about course structure, course goals, outcomes and preferences, we were able to launch our first Virtual Exchange in January 2022. The success of our partnership led to a presentation at the International Virtual Exchange Conference (IVEC) in October 2022, and then a MacPherson Institute Seed Grant in August 2023. This financial support from MacPherson has allowed the team to submit two manuscripts in 2024, one accepted, another in review, and the completion of this guide. Our partnership with USFQ remains strong, and we have continued to improve our course-embedded Virtual Exchange to better serve students’ needs.