11.6: Production Control for the Manufacturing Sector

Production control is a crucial function in operations management that ensures resources are used efficiently and effectively to meet production goals. It integrates purchasing, inventory control, and work scheduling to streamline production processes.

Purchasing

The process of acquiring the materials and services to be used in production is called purchasing (or procurement). For many products, the costs of material makes up about 50 percent of total manufacturing costs. Not surprisingly, materials acquisition gets a good deal of the operations manager’s time and attention.

Supplier Selection

Supplier selection is a critical aspect of purchasing. It involves choosing the best vendors to meet the company’s material or service requirements based on specific criteria. As a rule, there’s no shortage of vendors willing to supply materials, but the trick is finding the best suppliers. Operations managers must consider the following:

- Can the vendor supply the needed quantity of materials at a reasonable price?

- Is the quality good?

- Is the vendor reliable (will materials be delivered on time)?

- Does the vendor have a favourable reputation?

- Is the company easy to work with?

Use key performance indicators (KPIs) to assess potential vendors:

- Cost: Are the prices competitive?

- Quality: Do they meet the required standards consistently?

- Reliability: Are deliveries made on time?

- Capacity: Can they handle the required volume?

- Sustainability: Do they align with the company’s ethical and environmental goals?

Strategic supplier selection is important for the following reasons:

- Cost efficiency: Reducing production costs through competitive pricing.

- Quality assurance: Ensuring final products meet customer expectations.

- Risk mitigation: Reducing supply chain disruptions by working with reliable suppliers.

- Innovation: Collaborating with suppliers who offer advanced technologies or innovative solutions.

In summary, the integration of efficient purchasing and careful supplier selection can significantly enhance a company’s operational performance and competitive advantage.

Procurement

Technology has changed the way businesses buy things. Through modern procurement practices, companies use the Internet to interact with suppliers. The process is similar to the one you’d use to find a consumer good—say, a high-definition TV—over the Internet. To choose a TV, you might browse the websites of manufacturers like Sony, then shop for prices and buy on Amazon, the world’s largest online retailer.

If you were a purchasing manager using the Internet to buy parts and supplies, you’d follow basically the same process. You’d identify potential suppliers by going directly to private websites maintained by individual suppliers or to public sites that aggregate information on numerous suppliers. You could do your shopping through online catalogues, or you might participate in an online marketplace by indicating the type and quantity of materials you need and letting suppliers bid. Finally, just as you paid for your TV electronically, you could use a system called electronic data interchange (EDI) to process your transactions and transmit all your purchasing documents.

The Internet provides an additional benefit to purchasing managers by helping them communicate with suppliers and potential suppliers. They can use the Internet to give suppliers specifications for parts and supplies, encourage them to bid on future materials needs, alert them to changes in requirements, and give them instructions on doing business with their employers. Using the Internet for business purchasing cuts the costs of purchased products and saves administrative costs related to transactions. It’s also faster for procurement and fosters better communications.

Harley-Davidson maintains a Supplier Diversity policy for making procurement-related decisions. This decision area is concerned with optimizing the supply chain for the motorcycle manufacturer’s growth. The company’s policy ensures the optimal productivity and capacity of its supply chain based on the availability of a wide variety of suppliers. Success in this area of operations management depends on how policies and strategies address the bargaining power of suppliers, as described in the Five Forces Analysis of Harley-Davidson. Also, decisions about supply chain management take into account supply-related industry and market conditions, such as the trends shown in the PESTLE/PESTEL analysis of Harley-Davidson.[1]

Outsourcing in the Manufacturing Sector

Outsourcing in business refers to the practice of contracting out certain business functions, tasks, or processes to external vendors or service providers, rather than handling them in-house. This strategy is commonly employed by companies to reduce costs, gain access to specialized expertise, or increase efficiency by leveraging external resources. These tasks can include activities such as customer service, manufacturing, IT support, human resources, and more. A company may decide to outsource manufacturing to a foreign country where labour costs are lower, influencing both the location of operations and the logistics required to maintain supply chains. For example, Nike has been known for outsourcing the majority of its manufacturing, choosing to locate production in countries like Vietnam, China, and Indonesia. This allows Nike to focus on its product design and marketing while relying on external partners for labour-intensive tasks. This outsourcing model significantly impacts both its product/service strategy and supply chain decisions.

Some reasons companies outsource include:

- Companies might outsource to reduce costs

- Gain access to expertise, technology, and innovation they currently do not have

- To better focus on core business activities by outsourcing non-core activities

- Outsourcing provides flexibility in scaling operations up or down quickly

- Companies can reduce risks by sharing risks with, or transferring some risks to, external partners

- For global companies, outsourcing to different time zones can provide a 24-hour work cycle

While outsourcing provides numerous advantages, it also has some disadvantages, including:

- Ensuring quality standards are met

- Maintaining control over outsourced functions

- Risks of data breaches or the mishandling of sensitive information

- Communication issues such as language barriers or cultural differences

- Limited options to switch providers without incurring costs or disruptions

- Vulnerability if the company over-relies on the partner and the partner fails to deliver

- Risks of intellectual property theft or misuse by third-party providers

Outsourcing has become an increasingly popular option among manufacturers. For one thing, few companies have either the expertise or the inclination to produce everything needed to make a product. Today, more firms want to specialize in the processes that they perform best (core function) and outsource the rest. Companies also want to take advantage of outsourcing by linking up with suppliers located in regions with lower labour costs. Outsourcing can be local, regional, or even international, and companies can outsource everything from parts for their products, like automobile manufacturers do, to complete manufacturing of their products, like Nike and Apple do. Apple outsources the production of certain components (like chips or displays) to specialized manufacturers, enhancing both product quality and innovation.

Inventory Control

If a manufacturer runs out of the materials it needs for production, then production stops. In the past, many companies guarded against this possibility by keeping large inventories of materials on hand. It seemed like the thing to do at the time, but it often introduced a new problem—wasting money. Companies were paying for parts and other materials that they wouldn’t use for weeks or even months, and in the meantime, they were running up substantial storage and insurance costs. If the company redesigned its products, some parts might become obsolete before ever being used.

Most manufacturers have since learned that to remain competitive, they need to manage inventories more efficiently. This task requires that they strike a balance between two threats to productivity: losing production time because they’ve run out of materials and wasting money because they’re carrying too much inventory. The process of striking this balance is called inventory control, and companies now regularly rely on a variety of inventory-control methods.

Just-in-Time Production

One method is called Just-in-Time (JIT) production: the manufacturer arranges for materials to arrive at production facilities just in time to enter the manufacturing process. Parts and materials don’t sit unused for long periods, and the costs of “holding” inventory are significantly cut. JIT, however, requires considerable communication and cooperation between the manufacturer and the supplier. The manufacturer has to know what it needs and when. The supplier has to commit to supplying the right materials, of the right quality, at exactly the right time. Today many grocery stores use JIT systems to replenish stock based on sales data from its point-of-sale system, reducing wastage of perishable items.

Material Requirements Planning

A software tool called material requirements planning (MRP), relies on sales forecasts and ordering lead times for materials to calculate the quantity of each component part needed for production and then determine when they should be ordered or made. The detailed sales forecast is turned into a master production schedule (MPS), which MRP then expands into a forecast for the needed parts based on the bill of materials for each item in the forecast. A bill of materials is simply a list of the various parts that make up the end product. The role of MRP is to determine the anticipated need for each part based on the sales forecast and to place orders so that everything arrives just in time for production.

Inventory Management Software

Tools like SAP, Oracle NetSuite, or QuickBooks help automate inventory tracking and analysis. An example in the manufacturing sector is a car manufacturer that maintains a safety stock of critical components to avoid production halts due to supply chain disruptions. An example in the manufacturing sector. Point-of-sale (POS) systems track everything sold during a given time and provide information on how much of each item should be kept in inventory.

Work Scheduling

To control the timing of all operations, managers set up schedules: they select jobs to be performed during the production process, assign tasks to work groups, set timetables for the completion of tasks, and make sure that resources are available when and where they’re needed. There are a number of scheduling techniques. We’ll focus on two of the most common graphical tools—Gantt and PERT charts.

Gantt Charts

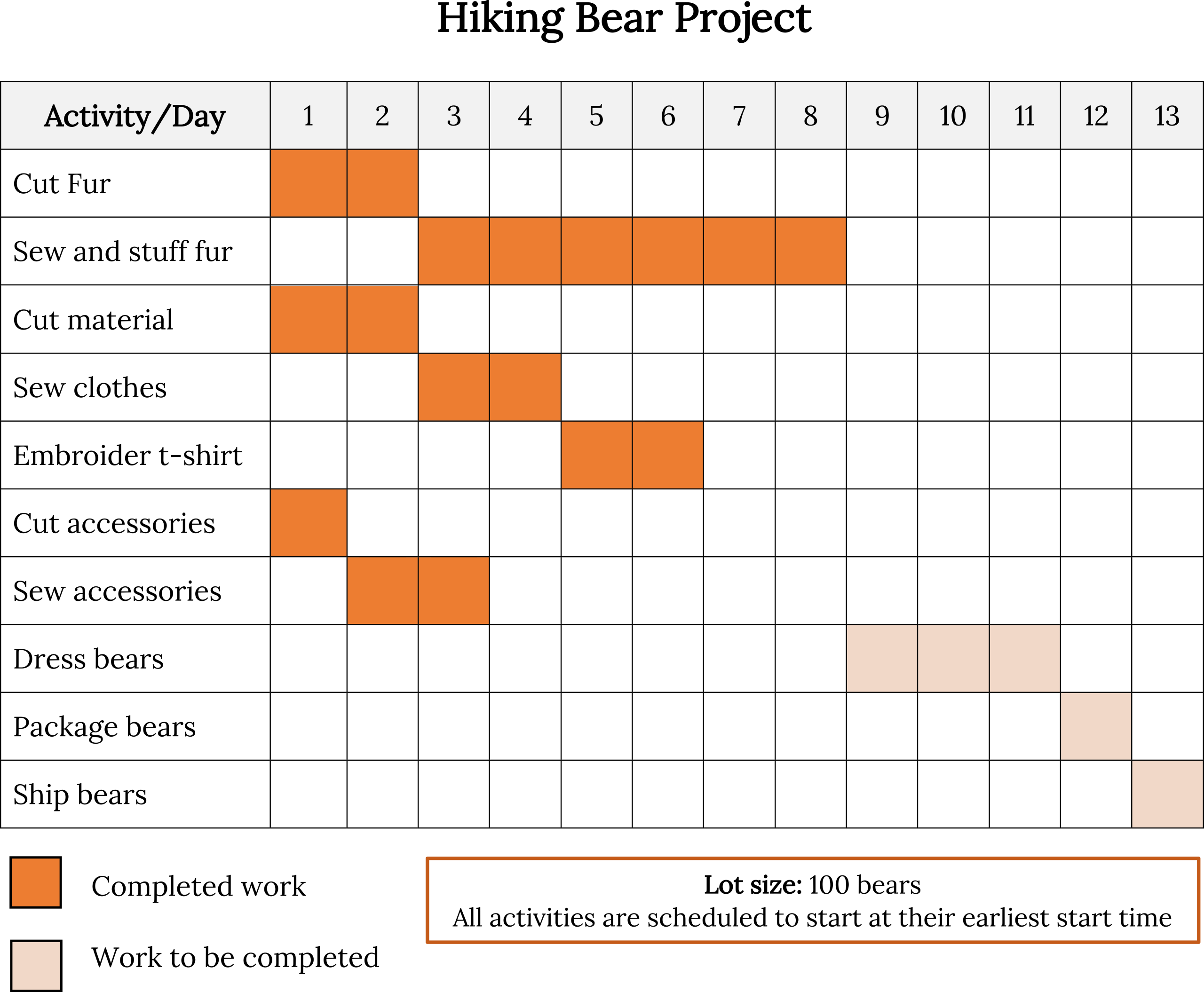

A Gantt chart, named after the designer, Henry Gantt, is an easy-to-use graphical tool that helps operations managers determine the status of projects. Let’s say that you’re in charge of making the “hiking bear” offered by the Toronto Teddy Bear Company. Figure 11.3 below shows a Gantt chart for the production of one hundred of these bears. It shows that several activities must be completed before the bears are dressed: the fur has to be cut, stuffed, and sewn; and the clothes and accessories must be made. Our Gantt chart tells us that by day six, all accessories and clothing have been made. The sewing and stuffing, however (which must be finished before the bears are dressed), isn’t scheduled for completion until the end of day eight. As operations manager, you’ll have to pay close attention to the progress of the sewing and stuffing operations to ensure that finished products are ready for shipment by their scheduled date.

PERT Charts

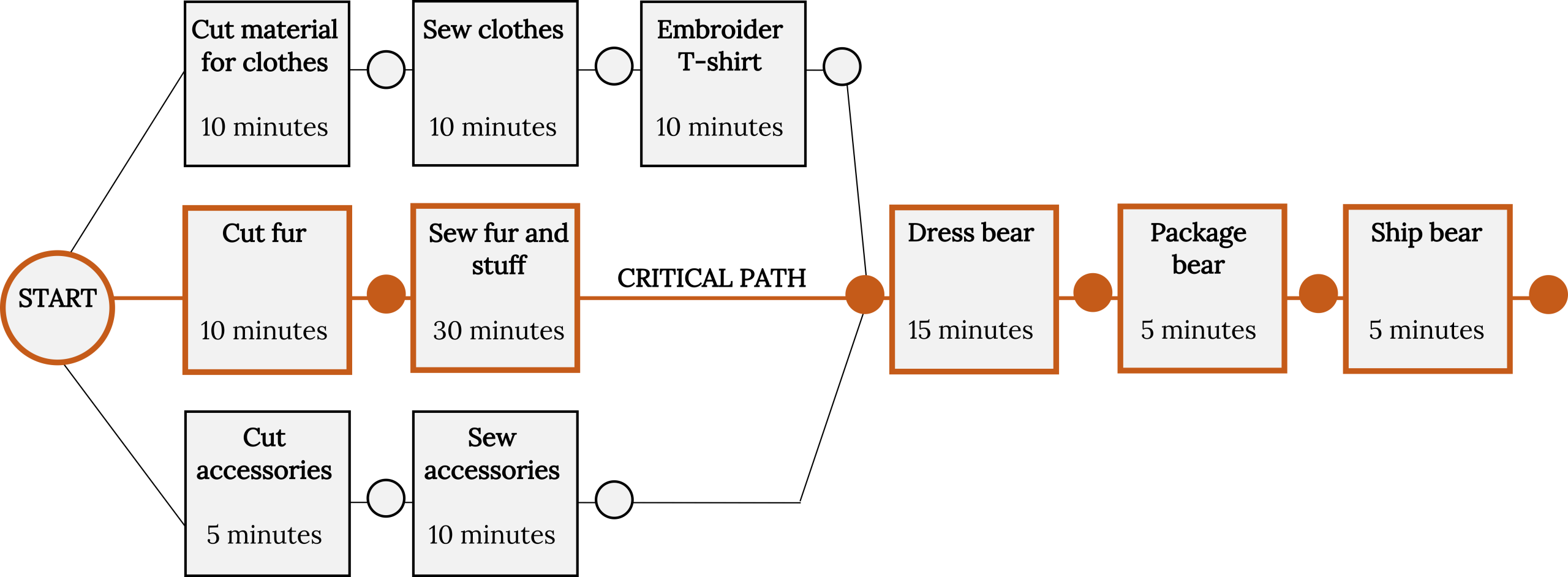

Gantt charts are useful when the production process is fairly simple and the activities aren’t interrelated. For more complex schedules, operations managers may use PERT charts. PERT (which stands for Program Evaluation and Review Technique) is designed to diagram the activities required to produce a good, specify the time required to perform each activity in the process, and organize activities in the most efficient sequence. It also identifies a critical path: the sequence of activities that will entail the greatest amount of time. Figure 11.4 is a PERT diagram showing the process for producing one “hiker” bear at Toronto Teddy Bear.

Our PERT chart shows how the activities involved in making a single bear are related. It indicates that the production process begins at the cutting station. Next, the fur that’s been cut for this particular bear moves first to the sewing and stuffing stations and then to the dressing station. At the same time that its fur moves through this sequence of steps, the bear’s clothes are cut and sewn, and its T-shirt is embroidered. Its backpack and tent accessories are also being made at the same time. Note that fur, clothes, and accessories all meet at the dressing station, where the bear is dressed and outfitted with its backpack. Finally, the finished bear is packaged and shipped to the customer’s house.

What was the critical path in this process? The path that took the longest amount of time was the sequence that included cutting, stuffing, dressing, packaging, and shipping—a sequence of steps taking sixty-five minutes. If you wanted to produce a bear more quickly, you’d have to save time on this path. Even if you saved the time on any of the other paths, you still wouldn’t finish the entire job any sooner: the finished clothes would just have to wait for the fur to be sewn and stuffed and moved to the dressing station. We can gain efficiency only by improving our performance on one or more of the activities along the critical path.

Media Attributions

“Container, Port, Ship image” by MICHOFF, used under the Pixabay license.

“Figure 11.3: Gantt Chart for Producing Teddy Bears” is reused from Example of a Gantt chart for a teddy bear. © 2022 by Kindred Grey, licensed CC BY 4.0.

“Figure 11.4: PERT Chart Showing Time and Activities in Making Teddy Bears” is reused from Example of a PERT chart for a teddy bear. © 2022 by Kindred Grey, licensed CC BY 4.0.

Image descriptions

Figure 11.3

A Gantt chart for the Hiking Bear Project organized with days numbered 1 through 13 along the top and a list of activities down the left side. The activities include “Cut Fur,” “Sew and stuff fur,” “Cut material,” “Sew clothes,” “Embroider t-shirt,” “Cut accessories,” “Sew accessories,” “Dress bears,” “Package bears,” and “Ship bears.” Orange shaded squares indicate completed work, while lighter beige squares represent work yet to be completed. The chart shows that “Cut Fur” starts on day 1 and is completed by day 3, and “Sew and stuff fur” is scheduled for days 4 to 7. Other tasks overlap on different days, indicating when they are planned to start and finish. “Dress bears”, “Package bears”, and “Ship bears” are marked in lighter beige, indicating “work to be completed”. The other tasks are marked with orange shaded squares that indicate “completed work”. There’s a legend at the bottom left, and an additional note at the bottom right states, “Lot size: 100 bears. All activities are scheduled to start at their earliest start time.”

Figure 11.4

A PERT chart illustrating the production process of a bear. The process begins with a “START” circle on the left, branching into three paths. The top path includes sequential steps labelled: “Cut material for clothes” (10 minutes), “Sew clothes” (10 minutes), and “Embroider T-shirt” (10 minutes). Tasks on the critical path are outlined in orange. The other tasks have e black outline. The path that runs through the middle is identified as the critical path and consists of: “Cut fur” (10 minutes), “Sew fur and stuff” (30 minutes), “Dress bear” (15 minutes), “Package bear” (5 minutes), and “Ship bear” (5 minutes). The bottom path lists: “Cut accessories” (5 minutes) and “Sew accessories” (10 minutes). All elements are connected by arrows indicating the process flow, with some steps linked by small circles suggesting possible intersections or decision points. The flow converges after the sewing of garments, accessories, and the stuffed bear to continue along the “CRITICAL PATH.”

- Meyer, P. (2024, October 1). Harley-Davidson operations management & productivity. Panmore Institute. ↵

The process of acquiring the materials and services to be used in production (also called procurement).

The practice of contracting out certain business functions, tasks, or processes to external vendors or service providers, rather than handling them in-house.

The task of striking a balance between two threats to productivity: not enough inventory and carrying too much inventory.

An inventory control method where the manufacturer arranges for materials to arrive at production facilities just in time to enter the manufacturing process.

A software tool that relies on sales forecasts and ordering lead times for materials to calculate the quantity of each part needed for production and determine when it should be ordered or made.

An easy-to-use graphical tool that helps operations managers determine the status of projects.

Charts designed to plot the activities required to produce a product, specify the time required to perform each activity in the process, and organize activities in the most efficient sequence.