1 Settler Colonialism is Alive and Well… in Sport?

Geena Denno

What does Sport have to do with Settler Colonialism?

Canada: our home on native land. From the law and economics, to education and even sport, colonialism has impacted every aspect of the life that we know as Canadians. The colonization of sport began with its use in Indian residential schools back in the 1880s and is found today at the 2010 Winter Olympics in Vancouver, Canada, amongst other recent events. Colonialism is fueled by the capitalist ideals that society holds, where industries can prosper from the extortion of land from a marginalized group. It is also embedded in today’s political, legal, and economic systems in Canada. So a social construct, such as sport, could be mobilized to either further colonize or decolonize society. Let’s start with a general debrief on settler colonialism, the stuff our history textbooks failed to mention. Who and what and when and where and why and how on earth did settler colonialism occur? As we celebrate Canada’s 153rd birthday with fireworks, barbeques with family, and a day off from work, did it ever occur to us how old this land really is? Or who truly owns it?

Where?

The “where” would be here, in Canada. Since time immemorial, Turtle Island – or what we now know as Canada, was inhabited by Indigenous people from more than 53 culturally and ethnically diverse groups (Settler Colonialism, 2015). It was on Turtle Island where the Europeans saw the land of opportunity, where the Italian John Cabot, as we famously recall from our Canadian history textbooks, completed his voyage across the Atlantic Ocean in 1497 (Early History of Canada, 2016). Jacques Cartier and Samuel de Champlain followed, creating several French cities along the coast of the St. Lawrence for farmers, fishers, and fur-traders (Early History of Canada, 2016). And so it began.

Who & When?

The “who”, the European settlers, began their systematic process of colonizing Turtle Island. Over the years, the Europeans began to outnumber the Indigenous peoples, asserting their sovereignty over Indigenous lands. This crime of colonization was well underway by the 1600s. The “when” really kicked into full-gear through this time and for three centuries following. Heck, it is still alive and well today. More of that later.

Why?

The “why” is quite clear. The slow invasion was strategically planned by the Europeans with the intention of eventually eradicating the Indigenous peoples along with their traditions and languages. By creating a power structure and social narrative, the Europeans pushed for control over land, imposing a government and Catholicism on Indigenous peoples. The Europeans saw Canada as a land of opportunity, where European industries and populations could expand. It really did not matter what got in their way. They saw opportunity.

What Happened & How?

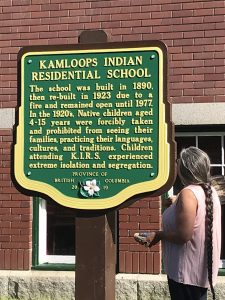

So comes the “what”. Treaties were initially signed in the early 1600s between the Europeans and the Indigenous peoples, visually and verbally declaring that both parties would share resources on land, taking only what they needed (Timeline: Indigenous Peoples, 2018). The Indigenous peoples would also share their supply of beaver pelts and other furs and in return the Europeans would give them access to their weaponry amongst other goods. All was fine between both parties until the Europeans began to violently break these treaties. How? The Europeans believed that they were taking ownership of the lands, not sharing, when signing treaties with Indigenous peoples. At some point, Indigenous communities had no choice but to continue signing treaties with the Europeans, as they provided assistance and protection under an ever-growing European government. By March of 1867, the federal government under the British Constitution Act took full authority over the Indigenous peoples and their lands, followed by the Indian Act in April of 1876 to further Euro-Canadian assimilation (Timeline: Indigenous Peoples, 2018). Under the confederation of Sir John A. MacDonald and the Catholic church, residential schools were authorized in 1883 to complete the national crime that began in the 1500s (Timeline: Indigenous Peoples, 2018). Children were taken from their birth families and suffered long-term trauma from the separation. It took decades of activism and pressure on the government to close residential schools, leading up to 1996 when the last facility was finally closed (Timeline: Indigenous Peoples, 2018). Fast-forward to present day, colonialist ideals and practices are still alive and well in varying capacities.

Present Day

Efforts to reconcile with Indigenous peoples have been active since the first official apology from Prime Minister Stephen Harper in 2008 (Timeline: Indigenous Peoples, 2018). Colonialism however remains embedded in the deep roots of the Canada we love and sing about. We saw it in the 1990 violent standoff in Oka, where the Mohawk had to physically block the expansion of a golf course on Kanesatake land. Then in the conflict between the commercial fishers and Mi’kmaq fishers of Nova Scotia in 1999 and again in 2020. Now, the TransCanada natural gas pipeline that is set to run through Wet’suwet’en land despite the protests against it. These are only some of the recent events that depict just how much the Canadian government cares to truly reconcile with Indigenous peoples.

The Colonization of Sport As We Know It

Sport has played a substantial role in Canada’s history in varying capacities. Although there are many more real-world applications of colonialism through sport, our focus in this chapter highlights the very first occurrence and some modern-day practices that followed. Dating back to the implementation of residential schools in 1883, thousands of Indigenous children were taken from their families and placed in these underfunded, poorly staffed, and abusive facilities. Sport was utilized as a disciplinary tool of cultural assimilation, making Indigenous children increasingly docile with the intention of eventually integrating them into Euro-Canadian society (Forsyth, 2013). Indigenous physical cultural practices and games were outlawed to be replaced with what we know as soccer, basketball, and hockey. Children were convinced that participating in such sports would provide a means of agency and pride, where in actuality they promoted more compliant and productive forms of behaviour.

Today, we still see colonialist ideals and influences in modern-day sport. Mega-events, such as the 2010 Vancouver Olympics have really put into perspective the lack of concern and stewardship of Indigenous lands by the Canadian government. The Games were located on stolen land, land that never had treaties and was never surrendered to the British Canadian government (Skyes & Hamzeh, 2018). Ski resorts also follow the same suit in Western Canada, as they are located on Indigenous lands. Entertaining the winter sports industry of settler colonialists has taken away the relationships Indigenous peoples have with their land (Skyes & Hamzeh, 2018). These resorts and access roads interfere with sacred Indigenous hunting grounds. This is yet another way the government has failed to legislate against the unfair treatment of Indigenous peoples and their land.

Sport itself is an entire industry, fueled by capitalists with a corporate agenda. If the agenda reports that Indigenous matters are of importance to the public, then the industry will provide a capitalist-solution. This is best found in the new marketing trend of “red-washing” (Millington et al., 2019). Red-washing allows corporations to promote their citizenship in the community by funding Indigenous sport programming for youth participation, for example (Millington et al., 2019). Sport is mobilized as a way to empower local youth and communities, however it is funded by the same corporations that believe that contributing to “social good” in Indigenous communities justifies their harmful operations on stolen land. Such distractions divert the public’s attention away from decolonization to false ideals of empowerment and partnership through sport. They also construct existing Indigenous sports organizations as “broken” and in need of developmental aid from settler interventions with little consideration of Indigenous social, cultural, and economic well being in broader historical and ongoing structural conditions (Millington et al., 2019).

Indigenous Activism Using Sport

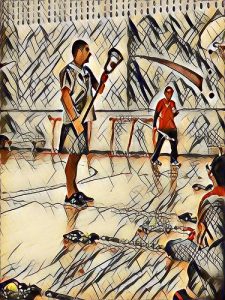

Despite colonialist influences on sport, sport can still be argued to be a vehicle for social change. In Indigenous communities today, sport has value in spiritual and healing potential within the context of Indigenous culture and practice (Campbell, 2017). The Creator’s Game was a popular Indigenous sport before European settlers renamed it “lacrosse” and changed the rules and field of play back in the 1600s (Marshall & Calder, 2017). Indigenous peoples were not allowed to play lacrosse, let alone professionally, until the Iroquois Nationals team was accepted in the 1990 World Lacrosse Championships (Downey, 2016, p. 3-5). The team consisted of a group of Haudenosaunee leaders who were seeking an outlet to renew the nation’s sovereignty by creating the Iroquois Nationals men’s team in 1983 (Downey, 2016, p. 3-5). The formation and successful acceptance of the team addressed the historical injustices against Indigenous peoples, publicly asserting the self-determination of the Haundenosunee people (Marshall & Calder, 2017). The North American Indigenous Games (NAIG) was then developed in 1990 to bring together Indigenous youth and celebrate their heritage through sport (Marshall & Calder, 2017). The Aboriginal Sport Circle (ASC) followed the development of the NAIG in 1995, in response to the demand from Indigenous peoples for accessible recreation and sports opportunities (Marshall & Calder, 2017).

Fast-forward to the 2000 Olympics where Waneek Horn-Miller, a Mohawk athlete became the first Indigenous woman from Canada to make it to an Olympics. As a child, she spent four months on the front lines of resistance during the Oka crisis in 1990, and was stabbed in the chest by a soldier’s bayonet (CBC News, 2020). Now in 2020, she is petitioning on a panel amongst other Indigenous Olympic athletes in a call to action upon governments, sporting officials, and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC). Horn-Miller praises organized sport for Indigenous youth, the ripple effects on their communities, and the importance of Indigenous role models for young athletes (CBC News, 2020).

The push for the fair treatment of Indigenous peoples has come from Indigenous peoples themselves, Indigenous athletes, and now Indigenous advocates in the public. In recent news, the Washington NFL team announced that their original team name, which was a racist slur against Indigenous peoples, and their mascot/logo of an Indigenous man in a Native headdress, would be changed (Sharrow et al., 2020). Pressure from sponsors and decades of criticism from Indigenous advocates made this change possible. Through planned demonstrations and campaigns, the collective voice of the public brought to light just how offensive the NFL team was in its name, mascot, and logo to Indigenous peoples (Monkman, 2020). Such activism could translate to similar changes in other professional sports teams and leagues that use Indigenous names or imagery, including the Chicago Blackhawks, the Atlanta Braves, and the Edmonton Eskimos among others (Monkman, 2020).

In the simplest of contexts, sports and recreation have played a large role in colonization, but also have the potential to promote decolonization. Canada has a deeply rooted history of colonial policy and practices where it has overthrown Indigenous political authority, cultural self-determination, and economic capacity in many horrendous ways. With this history, there is strong explanatory power in understanding how colonialist ideals and sport have become entangled. Sport was once used as a disciplinary tool of cultural assimilation, but is now considered an opportunity for social change. Those of us who are settlers on this land have a collective responsibility to learn about the ongoing history of settler colonialism in Canada but also to actively engage in methods of decolonization. Perhaps after reading this chapter, you’ll be mindful of the next ski resort you visit, the professional sports team you cheer for, or the sport you play. Reflect on the land you live, work, and play on. Consider the ways in which our education has truly failed us in learning about the true “Canadian” story. And the next time you sing the national anthem, remember that this is our home on native land.

References

Campbell, M. (2017, July 22). How Indigenous people in Canada are reclaiming lacrosse. Maclean’s. https://www.macleans.ca/society/how-indigenous-canadians-are-reclaiming-lacrosse/

CBC News. (2020). 5 years after Truth and Reconciliation, Indigenous athletes say sports programs still fall short. https://www.cbc.ca/news/indigenous/trc-calls-to-action-sports-indigenous-panel-2020-1.5619464.

Downey, A. (2016). “Mobilizing Indigenous self-determination in unexpected places.” Chronos McGill.

Early History of Canada. (2016). The Canada Guide. https://thecanadaguide.com/history/early-history/#:~:text=%20Quick%20Facts%20%201%20Britain%20and%20Europe,many%20pro-British%20loyalists%20fled%20to%20Canada.%20More%20

Forsyth, J. (2013). Bodies of meaning: Sports and games at Canadian residential schools. Aboriginal peoples and sport in Canada: Historical foundations and contemporary issues, 15-34.

Marshall, T.,, & Calder, J. (2017). Lacrosse: From Creator’s Game to Modern Sport. The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/lacrosse-from-creators-game-to-modern-sport

Millington, R., Giles, A. R., Hayhurst, L. M. C., van Luijk, N., & McSweeney, M. (2019). ‘Calling out’ corporate redwashing: the extractives industry, corporate social responsibility and sport for development in indigenous communities in Canada. Sport in Society, 22(12), 2122–2140. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2019.1567494

Monkman, L. (2020, July 13). Activists hope amateur sports teams will follow suit in changing racist team names. CBC. https://www.cbc.ca/news/indigenous/activists-hope-amateur-teams-name-changes-1.5648192

Norman, M. E., Hart, M., & Petherick, L. (2019). Indigenous Gender Reformations: Physical Culture, Settler Colonialism and the Politics of Containment. Sociology of Sport Journal, 36(2), 113–123. https://doi.org/10.1123/ssj.2018-0130

Settler Colonialism. (2015, August 4). Settler Colonialism. Global Social Theory. https://globalsocialtheory.org/concepts/settler-colonialism/

Sharrow, E. A., Tarsi, M. R., & Nteta, T. M. (2020). What’s in a Name? Symbolic Racism, Public Opinion, and the Controversy over the NFL’s Washington Football Team Name. Race and Social Problems. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12552-020-09305-0

Skyes, H., & Hamzeh, M. (2018). Anti-colonial critiques of sport mega-events. Leisure Studies 37(6). https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2018.1532449

Timeline: Indigenous Peoples. (2018). The Canadian Encyclopedia. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/timeline/first-nations