4 Basic Income Guarantee

Abby Carter

Sport Participation and Income

It is no secret that physical activity is beneficial to our health. While we like to convince ourselves that being active is a choice and under our control, that is not always the case. As with many other health behaviours, socioeconomic status can be a strong predictor of a person’s physical activity participation rates (Kamphuis et al., 2008). This is evident in sport participation rates, which show that having a higher income increases a person’s chance of participating in sport, across various sporting contexts (Breuer et al., 2011).

You may be thinking, “being active is free, people can go for a walk or run”. This belief is where the problem begins, because that is far from the truth. People of low socioeconomic status are more likely to report unsafe, unattractive, and insufficient neighbourhoods, which negatively impact their ability to be active (Kamphuis et al., 2008). Additional factors influencing their participation rates in physical activity and sport include a sense of belonging and networking within their neighbourhoods. Just think for a moment, would you want to go outside and exercise if the environment felt isolated, unsafe and uninviting? These factors prevent people of low socioeconomic status from engaging in simple, accessible, and free forms of physical activity. When you consider that sport can be out of reach for people of low income due to the associated costs such as equipment, travel, and registration fees, they are left with little opportunity to safely engage in physical activity of any form (Holt et al., 2011).

Lower rates of physical activity participation are just one of the ways socioeconomic status and income can influence a person’s overall health. Kamphuis and colleagues (2008) suggest that in order to reduce this disparity and inequality in health, intervention and policy changes would need to target lower socioeconomic groups at individual, household, and neighbourhood levels. You may be asking how this could be accomplished and what change could be made that would impact all of these levels. The answer: having a government implemented basic income guarantee (BIG).

Basic Income Guarantee

Basic income guarantee, also known as universal basic income, would involve each citizen receiving an unconditional income, regardless of their employment status (Ruckert et al., 2017). BIG serves as a method to increase a person’s income, which is a key social determinant of health (Raphael et al., 2019). The idea of having BIG in Canada has been cycling for decades and has been tested in small-scale trials, which showed very promising results (Mulvale, 2016). While there are some sceptics, you cannot deny that BIG would have a beneficial impact on Canadian citizens in lower socioeconomic classes.

The proposed implementation of BIG by the Green Party of Canada in 2015 serves as one example to how BIG would be distributed. Their plan was to replace the existing social supports (child tax benefit, Old Age Supplement and Guaranteed Income Supplement) with a taxable BIG payment, which would be taxed based on overall income (Mulvale, 2016). This would ensure those who rely on the existing services are still receiving support, in addition to those who could benefit from BIG. This would also prevent unnecessary funding to those with adequate incomes, as they would be taxed according to their yearly income. This seems like a no-brainer, it’s a reallocation of existing supports in a way that would eliminate the need for the individual applications that can currently make it challenging for individuals to seek financial support.

Once you begin to research the concept of BIG, it becomes clear that most aspects of a person’s life and health, such as food security and their environment are impacted by income (Raphael et al., 2019). For those living in poverty, the increase in income provided by BIG would improve health though various mechanisms including those which could promote physical activity participation (Ruckert et al., 2017).

Advantages of Basic Income Guarantee

Basic income guarantee can help remove several barriers that negatively impact the lives of people of low socioeconomic status. One topic commonly referred to when discussing BIG implementation is improving food security and hopefully this will give you some insight as to why existing support system are not effective. Since nutrition and a person’s environment make a significant contribution to overall health, they serve as examples of how BIG can improve the overall health and well-being of Canadians (Mulvale, 2016).

Foodbanks serve as an example of the current support systems available for people of low socioeconomic status; however, it is evident that they do not solve the problem of food insecurity (Wright & Wimer, 2016). A study by Nord and colleagues (2006) found that households with very low food security either were not aware of the resource or chose not to use the foodbank. The important question is: Why are those with low food security choosing to avoid the food bank? This question should raise flags, the people for whom this resource was designed are actively choosing to avoid it. Wright and Wimer (2016) found that people chose to not use the food banks because they felt they had a moral obligation to leave it for those who were in greater need, because waiting in the long lines had both social and economic costs, and because the poor food quality made them feel disrespected. Rather than investing in food banks, the government needs to invest in the people they are trying to reach. Having basic income would reduce reliance on food banks, and would allow people to use the money in a way that would suit them.

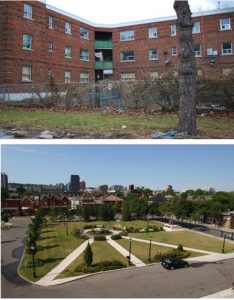

BIG also has the potential to improve the lives of people with low socioeconomic status through environmental improvements. For some individuals, BIG could provide them with extra money to allocate to recreation, which would increase the demand and desire for sporting/physical activity facilities such as playgrounds, running tracks, fields and basketball courts in low-income neighbourhoods (Holt et al., 2011). Having a supplemental income could also allow individuals to work fewer hours a week, which would allow them to spend more time at home and being social with their neighbours, both of which lead to increased opportunities to be physically active. This

sense of belonging in the community would allow people to feel safer and more welcomed by others, encouraging social interactions and group activities. This could allow for other beneficial outcomes such as community gardens, kids playing outside with friends, and neighbourhood gatherings. Personally, this sounds like a community that I would like to call home. With all the potential for social interaction, improved recreational facilities and the potential to increase recreational activity participation, the link between BIG and the potential for creating an environment which would increase recreational physical activity is clear.

Adverse health outcomes (physical, mental, and social health) are more likely to be encountered by the lowest 15-20% of income earners in Canada (Raphael et al., 2019). BIG has the potential to improve these statistics as it would reduce health risks, including those associated with food insecurity, unsafe environments, and low physical inactivity, and it would provide the opportunity to engage in health promoting behaviours.

Conclusion

With so much of Canada’s culture rooted in sport and physical activity, participation rates and the accessibility of sport can serve as a window into the concept of BIG. There is evidence supporting the claim that providing sport-specific funding for low-income families does not diminish the barriers to sport due to low income, as the time commitments, travel costs and limited facility access in low-income neighbourhoods are not diminished (Holt et al., 2011). This same pattern is observed with food insecurity and the implementation of food banks, which make the general public feel that the issue is solved when in reality the “solution” is not an effective one (Wright, 2016). Rather than addressing and solving the issues associated with low-income living, these systems serve as “band-aid” solutions and simply hide the problem. I believe that implementing BIG would change the way our country views government support, and it would shake the negative associations many people have with those who are on government support. With a universal basic income, there is no way to single out the people receiving government financial support, thus removing stigma and the stereotype that people relying on government support are unmotivated or lazy.

With the proven evidence from BIG trials in Canada, and given relatively steady poverty rates, we need to make an institutional change in our country. Those who do not feel they need BIG would be unlikely to notice a difference in their annual net income, but those on the lower end of the socioeconomic scale would notice a dramatic change. This would be a life-changing implementation for many Canadians.

You may be asking what you can do or how you can encourage this change? Together, we can advocate for BIG, speak to our local politicians and encourage them to consider how BIG could benefit citizens. No matter the social issue, effective change cannot happen unless we work collectively and advocate for all members of our community.

References

Breuer, C., Hallman, K., & Wicker, P. (2011). Determinants of sport participation in different sports. Managing Leisure, 16(4), 269-286.

Holt, N.L., Kingsley, B.C., Tink, L.N., & Scherer, J. (2011). Benefits and challenges associated with sport participation by children and parents from low-income families. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 12(5), 490-499.

Kamphuis, C.B.M., Lenthe, F.J.V., Giskes, K., Huisman, M., Brug, J., & Mackenback, J.P. (2008). Socioeconomic status, environmental and individual factors, and sports participation. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 40(1), 71-81.

Leung, E. (2018). Dilapidated apartment yard in Regent Park 2 [Online Image]. Flickr. https://www.flickr.com/photos/161174688@N08/44731824420

Mulvale, J.P. (2016). Next steps on the road to basic income in Canada. Journal of Sociology & Social Welfare, 43(3), 27-50.

Municipal Affairs and Housing. (2012). Hamilton neighbourhood park [Online Image]. Flickr. https://www.flickr.com/photos/93199753@N07/19892562223

Raphael, D., Bryant, T., & Mendley-Zambo, Z. (2019). Canada considers a basic income guarantee: Can it achieve it all? Health Promotion International, 34 (5), 1025-1031.

Ruckert, A., Huynh, C., & Labonté, R. (2017). Reducing health inequities: is universal basic income the way forward? Journal of Public Health, 40(1), 3-7.

Teunissen, P. (2018). The square [Online Image]. Flickr. https://www.flickr.com/photos/145835188@N03/40787849925

Wright, R.A., & Wimer, C. (2016). The cost of free assistance: Why low-income individuals do not access food pantries. Journal of Sociology & Social Welfare, 43(1), 71-94.