15 Breaking the Ice of White Privilege

Nicolette Didone

From the glitz and glamour of the costumes and makeup to the effortless looking performances on ice, figure skating appears to be a sport that allows any individual to express themselves freely. To the average audience member, the sport enables athletes to push their athletic and artistic boundaries on blades. However, many skaters of colour often feel discouraged to continue participating in a sport where its community does not necessarily welcome and uplift them.

Black Ice

Surya Bonaly is one of the few Black figure skaters who competed on the world stage. Due to her family being well off, Bonaly was provided the privilege to train and compete at the international level in figure skating. Bonaly was raised in France by her white adoptive parents, so she never saw her colour as being different when growing up (Duzyj, 2019). The sport of figure skating originated in Northern Europe where upper class men would glide on ponds as an exclusive leisure activity demonstrating privilege, wealth and sophistication (Kestnbaum, 2003). The historical traditions that have racialized figure skating as a ‘white sport’ for people with privilege continues to influence figure skating culture today. Despite figure skating being accessible to Bonaly, it did not necessarily mean that she was favoured in a sport that was predominantly white. Figure skating judging is subjective compared to most sports where competition is measured objectively by a timer or a scoreboard. Governing bodies enact rules based on their implicit judgements about what are the appropriate artistic ways for skaters to present themselves and the judges award artistic impression scores that are purely ideological and representational (Kestnbaum, 2003). Thus, figure skating has always been prone to judging scandals and discourse involving racial and nationalistic bias.

At the 1994 World Championships in Japan, Bonaly and home country favourite Yuka Sato were neck and neck with clean programs for the gold medal (Duzyj, 2019). The judges made the final decision to break the tie and awarded the gold medal to Sato (Duzyj, 2019). Bonaly was confident that the judges would award her the gold medal as she focused on her femininity and gracefulness rather than her triple and quadruple jumps (Duzyj, 2019). Frustrated with the judges and the outcome, she refused to stand on the podium and took off her silver medal (Duzyj, 2019). She received backlash from the media and audience for being a ‘sore loser’ and showing ‘poor sportsmanship’ (Duzyj, 2019). Bonaly’s podium protest represented her breaking point with the system; she felt she had been unfairly judged despite doing everything that they told her to do. Bonaly did not fit into the traditional image of a thin, often white ice princess stereotype that figure skating continues to uphold. Sport media legitimizes social inequality by highlighting the physical and personal attributes of Black athletes while shying away from the social structure of the system that continues to disproportionately affect people of colour more broadly (Hundley & Billings, 2010). The judges and sports media found any opportunity to label Bonaly as ‘different’, ‘exotic’, ‘an outsider’, ‘mystery’ and ‘will never fit in,’ because she challenged the historical narrative of figure skating as a predominantly white sport (Duzyj, 2019).

I personally resonated with Bonaly’s story because I also did not see my identity as a woman of colour as a limitation to what I could accomplish since I was raised in a white affluent family. I chose figure skating over other sports, because it was something that came naturally to me, and I advanced quickly at 9 years old compared to other girls who had started at the age of 3. I was aware that I looked different and skated differently, but I never let these thoughts stop me from participating. Looking back now, I realize that I had to be my own skating role model that I always wished I had had when I first started. Along with all other sports, figure skating is a product of white privilege and centuries of racism rooted in a structure created by society. This structure allocates societal ideologies and expectations to individuals based on the factors beyond one’s control, such as the colour of one’s skin .

Got Privilege?

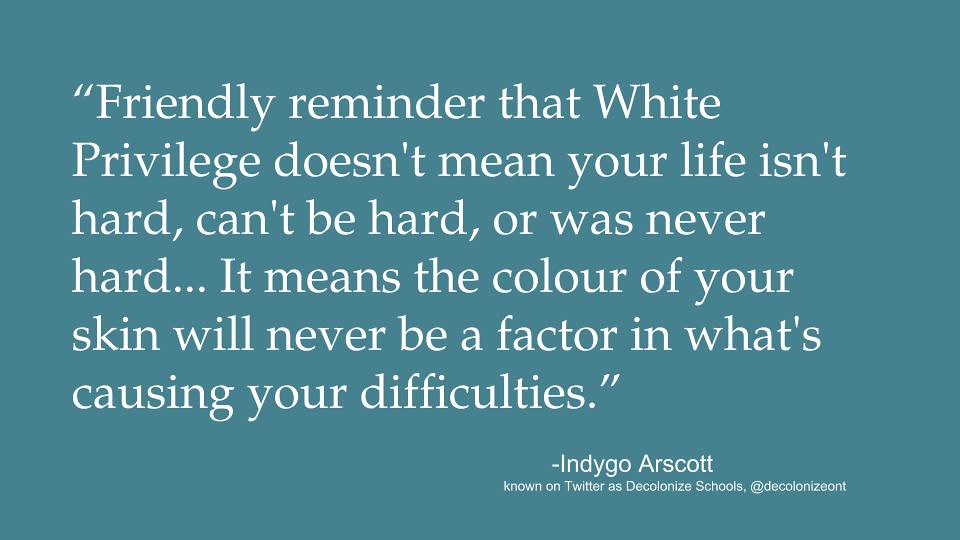

White privilege upholds the sociocultural construction of a racial hierarchy that prioritizes white people over people of colour. The foundation on which our society is built stems from a long history of white supremacy and the domination of minorities. As such, white privilege is the definitive idea that white people are inherently advantaged over people of colour simply by being identified and constructed as white by society. Whether or not an individual recognizes that their life is easier or attempts to dissociate from their white identity, privilege is still granted (Leonardo, 2004). Acknowledging and denying racial privilege often get used interchangeably when discussing racial injustices. For instance, the media is very vocal about racial tensions existing in the United States, however, there is less media coverage on race in Canada or other countries. This lack of media coverage does not mean racism doesn’t exist or it is not as bad, it means that there is more denial and lack of awareness.

Racism has been alive and well in Canada ever since the 1600s when the European settlers colonized Indigenous peoples who first inhabited the land (Historica Canada). Throughout history and current events, the idea of white people having good intentions behind recreating and reinforcing their own racial supremacy is pedagogical (Leonardo, 2004). The extent of most of our basic knowledge on racism outside of mass media is from the education system. From primary school age, the historical actions of white dominion, involving colonization, labour appropriation and systemic racism, are watered down by the education system to reinforce the innocence of whiteness (Leonardo, 2004). White people’s ignorance about the unearned advantages that they have over people of colour is a symptom of white privilege. The positive association between white people and their social identity to the extent of their actions are tainted by the illegitimacy of the past in textbooks, making their privilege a threat to their ‘moral’ social identity (Branscombe et al., 2007). The globalization of whiteness contributes to understanding white identity as it makes sense of ‘our’ politics, ‘our’ culture, and ‘our’ sport, making it easy for individuals to associate themselves with positive representations of a white identity (Long & Hylton, 2002). Society never questions the universal acceptance of white power, simply justifying whiteness with ‘that is just how the world works’ or ‘it is what it is.’

When discussing race, white people are generally scared and ashamed of feeling guilty, because they feel they are to blame for their privilege rather than they should think of racism as systemic. Blaming each other personally for racial privilege and injustice does not help the situation in any way. Unfortunately, not many people are willing to jeopardize their personal perception in society in order to contribute to shifting the culture of the world towards social change. Denying the existence of racial privilege and injustices only feeds more power to white supremacy and racism. Recognizing that white is a colour and accepting accountability to work for social fairness and justice allows white people to connect with minorities in “a sense of shared humanity and with a common goal of creating a more harmonious society” (Syed & Hill, 2011, p. 609).

A Demand for Change

The resurgence of the Black Lives Matter movement in 2020 has caused masses of people to come together and work towards social change and activism. After the countless deaths of Black people in America through police brutality, the Black community and the rest of the world has had enough. Celebrities, athletes, brands and corporate organizations have been speaking on racism and white privilege whether they were sharing their personal experiences or standing in allyship. Despite the seemingly good intent, some people, companies, and organizations have other priorities. Black Canadian figure skater, coach, and co-host of CBC’s That Figure Skating Show, Asher Hill, was outraged and devastated by Skate Canada’s racial equality statement that claims the organization is working towards anti-racism and leading social change in sport (Heroux, 2020). He always had felt that he constantly experienced racism and that he had always been aware of his skin colour when participating in figure skating (Heroux, 2020). Hill addresses Skate Canada for ignoring a complaint he made last year about misconduct on racism, misogyny, homophobia and abuse of skaters and coaches especially those of colour (Heroux, 2020). Hill says that Skate Canada had threated to take away his coaching license for speaking out and had continued to shut down the conversation of how to make actual change. Skate Canada denies this (Heroux, 2020).

Despite Skate Canada’s statement about practicing anti-racism, none of their actions has displayed anti-racism. It is disappointing that BIPOC athletes are sharing their past traumas and experiences with racism to begin tough conversations, but some people are not willing to listen and engage in the conversation. Social change does not occur from one individual, it occurs when everyone comes together. The idea of posting statements addressing Black Lives Matter is to authentically and ethically address racism and act accordingly outside of this in the real world. The key to practicing anti-racism is challenging whatever or whoever serves to maintain the supremacy and privilege of white people in this system. Now that the ice has be broken, how are you going to make a difference?

References

Branscombe, N. R., Schmitt, M. T., & Schiffhauer, K. (2006). Racial attitudes in response to thoughts of white privilege. European Journal of Social Psychology, 37(2), 203–215. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.348

Duzyj, M. (Director). (2019, March 1). Judgement (Season 1, Episode 3) [TV series episode]. In M. Duzyl (Executive Producer), Losers. Netflix. http://www.netflix.com

Heroux, D. (2020, June 5). Figure skater Asher Hill sees hypocrisy in racial equality statements. CBC Sports. https://www.cbc.ca/sports/floyd-george-sports-organizations-hypocrisy-asher-hill-1.5597217.

Historica Canada. Timeline: Indigenous Peoples. In the Canadian Encyclopedia. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/timeline/first-nations.

Hundley, H. L., & Billings, A. C. (Eds.). (2010). The Whiteness of Sport Media/Scholarship. In Examining Identity in Sports Media (pp. 153–172). story, Sage Publications.

Kestnbaum, E. (2003). Culture on ice: Figure skating & cultural meaning. Wesleyan University Press.

Leonardo, Z. (2004). The Color of Supremacy: Beyond the discourse of ‘white privilege’. Education Philosophy and Theory, 36(2), 137–152. https://doi.org/10.1111/ j.1469-5812.2004.00057.x

Long, J., & Hylton, K. (2002). Shades of white: An examination of whiteness in sport. Leisure Studies, 21(2), 87–103. https://doi.org/ 10.1080/02614360210152575

Netflix. (2019, March 22). Surya Bonaly’s Backflip|Official Clip|Losers|Netflix [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/_rE_4_CCEgc

Skate Canada [@SkateCanada]. (2020, June 2). [Tweet of Anti-Racism Statement]. Twitter. https://twitter.com/SkateCanada/status/1267905735033315328?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw%7Ctwcamp%5Etweetembed%7Ctwterm%5E1267905735033315328%7Ctwgr%5E%7Ctwcon%5Es1_&ref_url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cbc.ca%2Fsports%2Ffloyd-george-sports-organizations-hypocrisy-asher-hill-1.5597217

Syed, K. T., & Hill, A. (2011). Awakening to White Privilege and Power in Canada. Policy Futures in Education, 9(5), 608–615. https://doi.org/10.2304/pfie.2011.9.5.608

Whytock, K. (2018). Quotation: ‘Friendly reminder that White Privilege doesn’t mean your life isn’t hard, can’t be hard, or was never hard…It means the colour of your skin will never be a factor in what’s causing your difficulties’. [Photograph]. Flickr. https://www.flickr.com/photos/7815007@N07/42509004162