14 Writing

Writing is one of the key skills all successful students must acquire. In college courses, writing is how ideas are exchanged, from scholars to students and from students back to scholars. While the grade in some courses may be based mostly on class participation, oral reports, or multiple choice exams, writing is by far the single most important form of instruction and assessment. Professors expect you to learn by writing, and they will grade you on the basis of your writing.

As a form of communication, writing is different from oral communication in several ways. Professors expect writing to be well thought out and organized and to explain ideas fully. In oral communication, the listener can ask for clarification, but in written work, everything must be clear within the writing itself.

Our goal here is to introduce some important writing principles, if you’re not yet familiar with them, or to remind you of things you may have already learned in a writing course. As with all advice, always pay the most attention to what your professor says — the terms of a specific assignment may overrule a tip given here!

Academic writing refers to writing produced in a college environment. Often this is writing that responds to other writing — to the ideas or controversies that you’ll read about. While this definition sounds simple, academic writing may be very different from other types of writing you have done in the past. Often college students begin to understand what academic writing really means only after they receive negative feedback on their work.

The Writing Process

Writing professors distinguish between process and product. The expectations described here all involve the “product” you turn in on the due date. Although you should keep in mind what your product will look like, writing is more involved with how you get to that goal. “Process” concerns how you work to actually write a paper.

What do you actually do to get started? How do you organize your ideas? Why do you make changes along the way as you write? Thinking of writing as a process is important because writing is actually a complex activity. Even professional writers rarely sit down at a keyboard and write out an article beginning to end without stopping along the way to revise portions they have drafted, to move ideas around, or to revise their opening and thesis. Professionals and students alike often say they only realized what they wanted to say after they started to write. This is why many professors see writing as a way to learn. Many writing professors ask you to submit a draft for review before submitting a final paper.

How Can I Make the Process Work for Me?

No single set of steps automatically works best for everyone when writing a paper, but writers have found a number of steps helpful. Your job is to try out ways that your professor suggests and discover what works for you. As you’ll see in the following list, the process starts before you write a word.

Generally there are three stages in the writing process:

- Preparing before drafting, sometimes called prewriting

- Writing the draft

- Revising and editing

Involved in these three stages are a number of separate tasks—and that’s where you need to figure out what works best for you.

Preparing

Before you begin writing:

- Understand the requirements of the assignment.

- Conduct your research.

- Brainstorm ideas for your assignment based on the requirements, your course materials and your research.

- Outline your paper structure and note where your research will help to develope your ideas.

Writing the draft

Title the paper to identify your topic. This may sound obvious, but it needs to be said. Some students think of a paper as an exercise and write something like “Assignment 2: History 101” on the title page. Such a title gives no idea about how you are approaching the assignment or your topic. Your title should prepare your reader for what your paper is about or what you will argue.

In your introduction, define your topic and establish your approach or sense of purpose. Think of your introduction as an extension of your title. Professors, like all readers, appreciate feeling oriented by a clear opening.

Build from a thesis or a clearly stated sense of purpose. Many college assignments require you to make some form of an argument. To do that, you generally start with a statement that needs to be supported and build from there. Your thesis is that statement; it is a guiding assertion for the paper. Be clear in your own mind of the difference between your topic and your thesis. The topic is what your paper is about; the thesis is what you argue about the topic. Some assignments do not require an explicit argument and thesis, but even then you should make clear at the beginning your main emphasis, your purpose, or your most important idea.

Develop ideas patiently. You might, like many students, worry about boring your reader with too much detail or information. But college professors will not be bored by carefully explained ideas, well-selected examples, and relevant details.

Integrate, do not just plug in relevant quotations, graphs, and illustrations. Remember that a quotation, graph, or illustration does not make a point for you. You make the point first and then use such material to help back it up. Make sure the reader understands why you are using it and how it fits in at that place in your paper.

Document your sources appropriately. If your paper involves research of any kind, indicate clearly the use you make of outside sources. If you have used those sources well, there is no reason to hide them. Careful research and the thoughtful application of the ideas and evidence of others is part of what college professors value.

Revising and Editing

Revising

Revising suggests seeing again in a new light generated by all the thought that went into the first draft. Revising a draft usually involves significant changes including the following:

- Making organizational changes like the reordering of paragraphs (don’t forget that new transitions will be needed when you move paragraphs)

- Clarifying the thesis or adjustments between the thesis and supporting points that follow

- Cutting material that is unnecessary or irrelevant

- Adding new points to strengthen or clarify the presentation

Editing

Correcting a sentence early on may not be the best use of your time since you may cut the sentence entirely. Editing and proofreading are focused, late-stage activities for style and correctness. They are important final parts of the writing process, but they should not be confused with revision itself. Editing and proofreading a draft involve these steps:

- Careful spell-checking. This includes checking the spelling of names.

- Attention to sentence-level issues. Be especially attentive to sentence boundaries, subject-verb agreement, punctuation, and pronoun referents.

- You can also attend, at this stage, to matters of style.

Remember to get started on a writing assignment early so that you complete the first draft well before the due date, allowing you needed time for genuine revision and careful editing.

Understanding Your First Assignment

When you first get a writing assignment, pay attention first to keywords for how to approach the writing. These will also suggest how you may structure and develop your paper.

Assignment Terms

Look for terms like these in the assignment:

Summarize. To restate in your own words the main point or points of another’s work.

Define. To describe, explore, or characterize a keyword, idea, or phenomenon.

Classify. To group individual items by their shared characteristics, separate from other groups of items.

Compare/contrast. To explore significant likenesses and differences between two or more subjects.

Analyze. To break something, a phenomenon, or an idea into its parts and explain how those parts fit or work together.

Argue. To state a claim and support it with reasons and evidence.

Synthesize. To pull together varied pieces or ideas from two or more sources.

Assignment Questions

Sometimes the keywords listed don’t actually appear in the written assignment, but they are usually implied by the questions given in the assignment. What, why and how are common question words that require a certain kind of response. Look back at the keywords listed and think about which approaches relate to what, why, and how questions.

What questions usually prompt the writing of summaries, definitions, classifications, and sometimes compare-and-contrast essays.

Why and how questions typically prompt analysis, argument, and synthesis essays.

Successful academic writing starts with recognizing what the professor is requesting, or what you are required to do. So pay close attention to the assignment. Sometimes the essential information about an assignment is conveyed through class discussions, however, so be sure to listen for the keywords that will help you understand what the professor expects. If you feel the assignment does not give you a sense of direction, seek clarification. Ask questions that will lead to helpful answers.

Outlines and Marking Schemes

Some professors will include an outline of different sections that they expect to see in your paper along with marks for each section. It is important to ensure you cover each section with sufficient detail to provide material to achieve the marks.

Pay attention to the areas with the most marks and devote more space in your paper to those areas. If your discussion section is work 20 marks and your conclusion is work 5 marks, the amount of space for your conclusion should be much less.

Plagiarism—and How to Avoid It

Plagiarism is the unacknowledged use of material from a source. At the most obvious level, plagiarism involves using someone else’s words and ideas as if they were your own. There’s not much to say about copying another person’s work: it’s cheating, pure and simple. But plagiarism is not always so simple. Notice that our definition of plagiarism involves “words and ideas.” Let’s break that down a little further.

Words. Copying the words of another is clearly wrong. If you use another’s words, those words must be in quotation marks, and you must tell your reader where those words came from. But it is not enough to make a few surface changes in wording. You can’t just change some words and call the material yours; close, extended paraphrase is not acceptable.

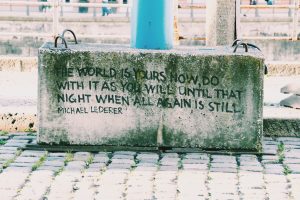

This street artist took the time to give credit to the author of this quote.

Ideas. Ideas are also a form of intellectual property. When you are summarizing an original idea, that is, stating the main idea in compressed form in language that does not come from the original, it could still be seen as plagiarism if the source is not cited.

This probably makes you wonder if you can write anything without citing a source. To help you sort out what ideas need to be cited and what not, think about these principles:

Common knowledge. There is no need to cite common knowledge. Common knowledge does not mean knowledge everyone has. It means knowledge that everyone can easily access. If the information or idea can be found in multiple sources and the information or idea remains constant from source to source, it can be considered common knowledge.

Distinct contributions. One does need to cite ideas that are distinct contributions. A distinct contribution need not be a discovery from the work of one person. It need only be an insight that is not commonly expressed and not universally agreed upon.

Disputable figures. Always remember that numbers are only as good as the sources they come from. If you use numbers like attendance figures, unemployment rates, or demographic profiles or any statistics at all, always cite your source of those numbers.

Forms of Citation

You should generally check with your professors about their preferred form of citation when you write papers for courses. No one standard is used in all academic papers. You can learn about the three major forms or styles used in most any college writing handbook and on many Web sites for college writers:

- The Modern Language Association (MLA) system of citation is widely used but is most commonly adopted in humanities courses, particularly literature courses.

- The American Psychological Association (APA) system of citation is most common in the social sciences.

- The Chicago Manual of Style is widely used but perhaps most commonly in history courses.

Key Takeaways

- Academic writing through written assignments is one way that professors use to help you learn course concepts and check your understanding of course concepts.

- The final assignment you turn in is the product, however, this chapter is interested in the process of writing that includes three major steps: preparing, writing the draft, and revising and editing.

- Preparing before you write includes understanding your assignment, researching, brainstorming and outlining.

- Writing the draft starts with a good title, then developing a purpose or thesis, developing ideas, and integrating ideas from your course materials and research.

- Revising is making changes to the organization, logic or details to strengthen your work while editing is paying final attention to spelling, grammar, punctuation, sentences and style.

- Before you begin an assignment, understand what product the assignment is asking you to produce and use outlines and marking schemes to ensure you give specific areas of your assignment appropriate space.

- Plagiarism is representing another’s words or ideas as your own. This can include blatant copying or using resources without proper citation. Avoid this when incorporating research into your writing.