9.2 Discussion

The word research can be traced back to the 16th century French recherche. It means “to go about seeking…” As a social scientist, there are few things I love more than “to go about seeking.” Mostly, I seek ways of contributing to solving critical problems, often related to equity and well-being. The research methods I use are my trusty “tools of the trade”; I see them as dependable old friends. But I also approach learning new methods with the zeal of a wilderness tripper finding a new map. The more attentive I am to all the map’s details and intricacies, the more exciting research adventures there are to be had.

I admit, my enthusiasm for methods is peculiar. Though I have research colleagues who share my passion, when your teaching slot is late Friday afternoons in the winter in Canada, chances that your students will view learning about methods with as much enthusiasm as I do are low. I can’t do anything about the cold and the dark or my time slot, but I am determined to draw my students into the excitement of research methods.

I divided the course into two parts. In part 1, we worked on developing skills of critical reading and thinking, and academic writing skills. I teach them how to do a focused library search, manage their citations, conduct a literature review and produce an annotated bibliography. These are some of the building blocks of research – the kinds of things you won’t get very far without knowing how to do. To make it more engaging for the students, I invited them to choose their own topics for this background work, in preparation for what they would then do in the next section.

Part 2 of the course was devoted to learning a range of specific research methods. We began with an intense active learning class on Research Ethics. Each student also completed the Tri-Council Certificate of Research Ethics (CORE) and submitted a two-page reflection CORE. We followed this with a class discussion about the foundational and guiding role of ethics in all research. Then we prepared to dive in. This chapter is about Part 2 of the course.

What I Did

A wide and diverse range of methods are used in Social Sciences research. My job was to introduce my students to some of them. I had only six weeks to do it, and there was no way I could cover everything. My goal was simply to get students interested and give them a glimpse of the kinds of things academic researchers think about as we approach our work: things like positionality, theory, bias, ethics, sampling strategies, data collection and analysis, and the process of intentionally identifying the strengths and limitations of our work. One of my goals was to help them see that the methods we use establish the academic credibility of our work.

I also wanted this unit to change the way they approach reading academic studies. So often students have told me that they like to gloss over the methods section of academic studies and just get to the “important” bits. To me, success would be changing this pattern entirely. It would be making it so that even if a student was new to a method in a particular study, they would read through it carefully and critically, have good questions to ask and be able to make a basic assessment as to the study’s overall merit. They would see that the research methods aren’t boring and dry. In fact, the opposite is true. They are core to the “important bits.”

I introduced the assignment at the beginning of the unit and using some of my own work as examples, I walked them through what they would be required to do: in groups, give a presentation in which they would teach the class about one method that is used in social science research.

The students then organized themselves into eight groups of approximately three people. Each group chose from a selection of twelve studies that I had curated for the class. I was intentional about choosing research done by several researchers in our own small department, and I was not surprised when these were especially popular choices among the students. Though I encouraged students to choose a study based on a research question that interested them, I reminded them that their main purpose was to pay attention to the methods. Their choices included an ethnography of Muslim girls in Canada, a qualitative study of sex and religion in Canada, a content analysis of American mega-church websites, and a quantitative study of religious involvement and adolescent risk behaviours and violence.

I was intentional about including several studies that were rooted in Indigenous research methods. One of these involved the application of “Two-Eyed Seeing” as a decolonizing methodology; another used a community-based research method to explore the role of ceremonies in the lives of urban Indigenous youth. As a class, we read the Tri-Council Policy Statement Chapter 9: Research Involving the First Nations, Inuit, and Métis Peoples of Canada and had a long and intentional discussion about positionality and the importance of ethical and reciprocal partnerships, especially when non-Indigenous scholars are engaged in Indigenous research.

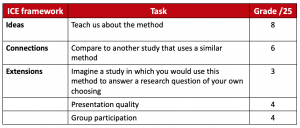

You may notice that I have yet to tell you about how and why I used ICE. If it seems like an afterthought in my description, it’s because it was an afterthought in what I did. Originally, I had intended to use ICE as an assessment tool. I realized that if I was using ICE, it would also necessarily inform the design of the assignment itself: how could I assess Connections and Extensions if I hadn’t asked them to make any throughout the course? In the end, once I started making my rubric, I realized I needed to redesign the assignment. Originally, I planned that through their Methods presentation, students would need to demonstrate a clear understanding of an Idea (the method). When I started using ICE, it helped me see that I also needed to ask them to make Connections. I did this by asking them to find a second study that used the same method, and compare, contrast, and articulate relationships (Connections) between the way the method was used in the first study and the way the method was used in a second, complementary study. ICE also pushed me to think about Extensions. I added a third component in which the students were responsible for extending their thinking beyond the work of other scholars and towards their own interests. Here is a more detailed outline of each step as it appeared in the final assignment.

Step 1: Ideas and Information

This step was about learning the basics. Using the method in the study each group had chosen as an illustrative example, the students were required to teach the method to the class.

Based on background reading beyond the study their group had chosen, they needed to tell us more about the method. Some of this they would learn from class lectures, some from their own further investigation. I didn’t have a singular textbook, but rather brought multiple methods books into the classroom, and had other resources on hold at the library that the students were free to consult. Since this was a second-year class and the topic area was new, I curated what I would consider “entry-level” questions about the various research methods that the students were discovering

- When and out of what discipline did it originate?

- What kinds of research questions is it useful for answering?

- What kind of theoretical framework is it based on?

- How versatile or adaptable do researchers find it?

- What kinds of ethical issues would researchers need to consider in relation to this particular method?

- What ethical issues were considered in the study you read?

- Every method has strengths and limitations, please tell us what they are in this particular method.

- How did the researcher in your study maximize the strengths and minimize the weakness? Does the researcher collect or generate data? If so, what tools or approaches are used?

As a first step, I walked the students through these questions as a full class, using several different studies as examples. My students were all new to these kinds of methods, and I made it clear that I was not expecting an expert analysis. I wanted a basic overview, and some careful thought into how this method works.

Step 2: Connections

The next goal of the assignment was to help the student create links between what they had learned in step 1 (with their primary study) and another second study. I wanted them to see that while researchers often make different methodological decisions, there are basic strategies that are transferred from method to method. They were to compare and contrast the way that the method was utilized between the two studies. (This was worth 5/25 marks.) Comparing and contrasting two studies was a skill that my students had already brought with them to class from their first-year studies, so a short in-class review was all that was needed to scaffold this assignment.

Step 3: Extensions

The goal was to extrapolate from what they had learned in steps 1 and 2 and apply their learning to something novel: their own ideas. I put this step in, frankly, because I was using ICE. This meant that if I wanted to use the entire spectrum of the framework, I needed to make an Extension a legitimate part of the assignment. The students were required to imagine a research question that interested them: one that they could answer using the method they had been learning about. They then had to design the study. This was worth 2 marks out of 25. For their own study, they still had to go through all the questions that they had considered in the studies they had looked at in Steps 1 and 2. What strengths and weaknesses does this method have in relation to your research question? What ethical issues do you anticipate? The real question was: so now you know what you know about this method, let’s think about what can you do with it!

Note that the final 4/25 grade points were for group participation, and 4/25 for the quality of the presentation itself) which were valuable, but that I will not discuss in this chapter. Here is a breakdown of the final grading.