Chapter 1. Introduction to the ICE Model

1.1 Getting Started

Sue Fostaty Young – Queen’s University

Have you ever told a student that you were expecting more of an answer to an exam question or homework assignment only to have that student resubmit with more words or more pages but not more of an answer? Or had students come by for office hours, disappointed in the grades on their assignments because, according to them, everything in their paper was ‘right’? Here, we share a model of learning and assessment that supplies instructors and students with a framework and vocabulary that facilitates communication about what learning looks like. In naming, framing, and providing a vocabulary, the model helps organize instructors’ and students’ thinking about learning and, in so doing, helps both groups become more purposeful in planning for the improvement of learning: the ICE model.

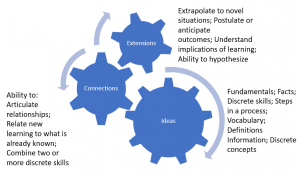

ICE is an acronym for Ideas, Connections, and Extensions – three qualitatively different frames of learning. The image above depicts each frame as an interconnected cogwheel. The intent is to illustrate that as change, or growth, occurs in any one frame of learning, the other frames are also likely to become susceptible to change.

Ideas can be conceptualized as the bits and pieces of learning. They are represented by things like discrete pieces of information, disciplinary vocabulary, steps in a process, and basic facts. Anything a student can recall, look up in their notes or in a textbook is an Idea. So, in history, for example, being able to recall names, dates, and events would be a demonstration of Ideas–based learning. In math, being able to complete ‘plug and chug’ equations accurately would indicate Ideas–based success. In an activity like basketball, it might be knowing the rules of the game or being able to perform a single, discrete skill like dribbling or completing a pass.

Connections are of two kinds – content-related Connections and those that involve personal meaning-making on the part of the student. In our history example, a Connection might be that students are able to articulate cause and effect relationships between historical events or perhaps begin to understand their own family’s emigration patterns in relation to world events. In math, students might be able to select appropriate equations relative to the characteristics of a problem. And in basketball, players would be able to combine two discrete skills, like running and dribbling, into a successful, more complex function. We’re hoping that, as you’re reading this, you’re thinking of your own instructional context, discerning the types of learning you’re expecting from your students, or undertaking yourself. In doing that, you’d be seeking to make Connections of your own, to what we’re presenting, through the process of meaning-making.

Extensions occur when students are able to appreciate the implications of their learning or develop the ability to use their learning in an entirely new context beyond the original learning environment. Using our history example, that might mean that students develop the capacity to interpret current events through new perspectives in ways that enable them to anticipate the evolution of global events. In math, the ability to make Extensions might enable students to create an equation as an expression of an unfamiliar problem. An Extension in basketball may be that a player becomes able to interpret play to the extent that they can pass to a spot on the court in anticipation of their teammate’s position.

Important to note is that each set of examples describe different ways of being ‘right’. So, going back to this chapter’s opening scenario of students who produced accurate term papers in which everything ‘was right’ we can determine that they did well in conveying Ideas but the purpose of the term paper was likely for them to articulate Connections and perhaps even to push toward Extensions. One Business prof, disappointed in the calibre of responses to a case study assignment, explained it to his students like this:

“When I gave you the case study to work on, it was as if I had given you a broken toaster. Some of you took that ‘toaster’ and pointed out all the pieces that were broken. And you were right, but you stopped there. A few others of you pointed out all the parts of the toaster that were broken and told me how the broken parts were affecting all the other parts. You were right, but you stopped there. Very few of you pointed out the parts that were broken, how those parts were affecting the toaster as a whole, and then told me how to fix the toaster and how to prevent it from breaking again. That’s what I wanted to see in your approach to the case study.”

Adapted from Fostaty Young, S. & Wilson, R. (2000). Assessment & Learning: The ICE Approach. Portage and Main Press

The professor’s explanation aligns directly with the frames of learning represented in ICE. Note that each frame of learning that’s described, Ideas, Connections, and Extensions, represents a qualitative – not quantitative – difference. That is to say that students aren’t being asked to do more of the same thing in each successive frame – they are doing qualitatively different things. Gaining a better grade on the case study assignment wasn’t a matter of pointing out more ‘broken pieces’; it required different frames of cognitive processing.

It’s tempting to think of Extensions as being the most valuable type of learning and, in some cases in post-secondary education, that is the type of learning we hope to foster. That said, in being able to name different frames of learning we have the potential to become more purposeful in structuring the learning environment in ways that are aligned with our intentions for learning. There are times when it’s essential for students to acquire Ideas and only Ideas. And as tempting as it might be to think that first year is for the acquisition of Ideas, second and third years are for Connections and that undergrads can’t possibly be capable of making Extensions until 4th year, consider learning as a non-linear, recursive loop rather than as a linear progression. If learning is recursive in the way that ICE conceptualizes it to be, then students, no matter where they are in their program, should be in a constant state of making Connections, and perhaps Extensions, then seeking out additional Ideas that contribute to the development of new Connections – and that the Connections and Extensions made in first year are merely qualitatively different than those made in subsequent years.

Instructors appreciate that in having ICE as a framework to organize their thinking about learning, they become better able to be purposeful in their teaching. They can plan instruction in ways that target specific frames of learning: lectures, short videos, or pre-readings to support the acquisition of Ideas; providing and inviting students to share examples of real-life manifestations of theoretical concepts or using classroom learning activities for meaning-making Connections; and inviting hypothesizing, extrapolation and asking “why do you suppose” questions as nudges toward Extensions.

ICE is a comprehensive model that captures a complex conception of learning and conveys it in a simplified, but not simplistic, way. It differs fundamentally from models like Bloom’s Taxonomy. Whereas Bloom’s conceptualizes three discrete domains of learning, ICE conceptualizes learning as an integrative process. Where Bloom’s hierarchical model suggests that competence at lower levels is a prerequisite for success at subsequent levels of learning, ICE represents an ongoing, non-linear, non-hierarchical learning loop of developing expertise. From a Bloomsian perspective, it makes perfect sense that learning (and teaching) must start at the level of Remembering, hence the predominance of courses and programs that begin with fundamentals, memorization, and rudiments of the discipline. Because ICE conceptualizes learning in a non-hierarchical way, many instructors actually find it more beneficial to begin their teaching at Connections (with students’ own experience) rather than with Ideas. Instructors’ experience is that when students begin with meaning-making, they have an easier time retaining Ideas. Without the foundation of relevance, students have no place to ‘hang the Ideas’ so they tend to lose them almost immediately after writing their exams. It’s the active process of meaning-making where real (lasting) learning occurs.

Still, what instructors mention most often is their appreciation of the accessible language of the ICE framework. They find that in having a shared language about learning it’s easier to create a sense of community in their classrooms, virtual or face-to-face – a language that transfers across disciplines and that students are able to apply across contexts, even if an instructor they’re working with isn’t actively using the model.