8.2 Discussion

Key components of the course included: mentor visits; tutorial discussions; journal writing and reflection; required readings and resource reviews. Mentors themselves provided feedback to students about their performance, specifically relating to communication skills and professional interactions during community visits, with their summaries documented in the students’ final evaluations. As an instructor, it was my responsibility to determine the students’ ability to synthesize the various components of the course and demonstrate their learning. This was done through their reflective journal entries and tutorial participation. A workshop during the course orientation class, facilitated by experts in the field of reflective practice, provided definitions, guidelines, and examples of reflective journal entries along with in-class practice exercises. I reviewed the students’ journal submissions at the mid-point of the course to provide formative feedback and again at the conclusion of the course for summative feedback for this pass/fail course. In both reviews, the ICE/ORID rubric was used to evaluate and provide constructive feedback, both narrative and visual, for the students. This allowed students to see their current performance along with areas of strength and weakness so they could plan for improved efforts in targeted areas. The beauty of using the ICE/ORID rubric was in its simplicity as a visual feedback tool as well as its capacity to stimulate detailed comments from the instructor. To me, it was apparent that the ICE model transformed the content areas of assessment into multi-dimensional feedback. This was an exciting revelation for me and led to a significant improvement in the feedback I was able to provide to students. The case study of one patient mentor and the student with whom he was matched, along with the customized assessment rubric for the course, are found at the conclusion of this chapter.

Using ICE as part of the assessment framework for the course was not the only benefit, as I also reviewed the rubric when planning tutorial agendas and discussion topics. My approach to tutorials was to collaborate with students in the initial meeting in the development of ground rules so that we agreed about how our discussions would unfold, ensuring student engagement and active participation. The ICE model broadened and deepened the quality of the discussions. For example, the issue of student H’s dilemma about offering assistance to his mentor at a grocery store became an hour-long discussion addressing topics of ‘helping etiquette’, socially acceptable language, us vs them bias, community accessibility, and funding discrepancies. The discussion continued and broadened in subsequent tutorials to include stem cell research, gaps in service provision, and personal assumptions about politically correct behaviour. Key messages from tutorials were documented in the students’ reflective journal entries. A rich discussion arose in every tutorial, with planned breaks frequently forgotten and respect for scheduled end-times often ignored. The energy was palpable and the learning, according to students’ course evaluations, valuable and keenly appreciated. Evidence of the influence of ICE on tutorial discussions was prominent in many ways. Some examples are provided here:

- Ideas—Students shared diverse and numerous experiences relating to their own mentors and other mentors whom they heard about in tutorials. They described observations related to specific issues such as accessibility and social determinants of health that impacted their mentors. Students demonstrated a willingness for self-exploration along with new levels of awareness and learning. For example, many identified biases, assumptions and/or stereotypical attitudes of which they were previously unaware.

- Connections—Students gained the ability to compare and contrast their experiences with those of student colleagues during tutorial discussions, noting similarities and differences and making sense of them. These connections were often linked to previous personal experiences. They heard about others’ judgments, assumptions, and attitudes leading to new deeper awareness of commonalities and differences.

- Extensions —Overarching themes that the students became aware of, learned from, and speculated about for patients/clients within the larger healthcare system and their own professional organizations arose during tutorial discussions. They considered how new levels of awareness, knowledge, and understanding affected their immediate personal and/or professional self-image. They speculated about their future professional identities and the influence of learning from their mentors and one another. They wondered what new insights might be taken into upcoming clinical fieldwork and beyond into professional practice, such as issues of advocacy, client-therapist boundaries, and health policy.

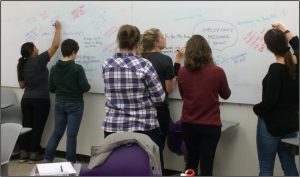

The last tutorial of the course culminated in a whiteboard collaborative exercise to gather students’ collective lessons learned in response to the question “So What?”. Numerous themes were identified and shared, resulting in the construction of a visual representation which was often included in the students’ journals as a cue for concluding comments. (See photo and text box below)

So What? Lessons Learned in OT825, 2013

|

When I initially adopted the ICE framework, I fell into the trap of assuming that reflecting at the level of Extensions was the ultimate goal, an example of the kind of linear thinking described by the editors of this book. With experience in using ICE, I learned that students often benefitted from returning to Ideas to reflect more carefully on the details of their observations and experiences before their natural tendency to jump to Connections or Extensions. The process of reflecting is cyclical in nature. It is enhanced when one returns to previous journal entries to consider additional thoughts that stimulate new ideas or highlight how one’s perceptions may have shifted or changed in subtle or even substantive ways. This often occurred, for instance, when a student became aware of a previous assumption they held about their patient mentor, the healthcare system, or their own understanding of health challenges. I detected variations in the students’ use of language and terminology that developed over the duration of the course, perhaps due to mentors’ choice of words, course reading materials, and peer discussions. Students at times were aware of these developments with many describing them as personal ‘aha’ moments of realization. Feedback that highlighted these shifts was used to further encourage students’ learning. The opportunity for students to share, and occasionally debate, differing points of view within tutorials was felt to be a significant advantage of the course structure and content.

During the final course tutorial students often admitted, with some reluctance, that they had more questions than when the course began. This admission was rewarded when I reframed their comments as evidence of successful first steps on a complex journey of learning about and appreciating the experience of chronic illness or disability. By raising questions, exposing stereotypes and assumptions, and being challenged by patient mentors, peers, instructors, and themselves, they were better positioned to continue the journey of lifelong learning. I encouraged students to continue to engage in reflective journaling in their formal education and beyond in their practice environments, using ICE to foster ongoing professional development.