2 Femme Fatale: Exploring the Dangers of the Gender Binary in Macbeth

Alyssa Mendonca

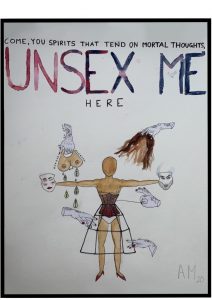

William Shakespeare’s Macbeth explores the link between gender and power, often associating callousness and brutality with ‘true’ masculinity. The catalyst of the tragedy lies in the Macbeths’, especially Lady Macbeth’s, view of manliness as an internal essential while antithetically insisting on outward acts as ‘proof’ of it. I suggest that the reason for their downfall is due to this irreconcilable view of gender. My adaptation of act 1 scene 5 highlights the inherent performativity of gender by portraying Lady Macbeth as a faceless drag queen being stripped of her external feminizing garments by the non-binary witches. Thus, the “unsexing” scene in Macbeth illustrates Shakespeare’s emphasis on the performance of gender and the existential dangers of viewing it as an essence rather than a projected exteriority.

I chose to represent Lady Macbeth as a faceless drag queen because the drag industry emphasizes gender performativity, she is reminiscent of Shakespearean cross-gendered casting, and it highlights the loss of identity as a consequence of gender essentialism. Naomi Jacobsen reminds us that Shakespearean theatre began as a “cross-gender form” (“Women Merely Players” 00:15:25-00:15:30); young boys in feminine costumes appeared on stage because it was one of the few places one could “discuss a woman having power because in fact she didn’t really have [it]” (00:08:18-00:08:23). Lady Macbeth seems the play’s catalytic female powerhouse however Shakespeare reminds us that her gender is performative: “Come, you spirits / That tend on mortal thoughts, unsex me here” (1.5.47-48). This passage is traditionally understood to be Lady Macbeth’s invitation to be stripped of her feminine weakness however, considering the role’s being originally played by a male, the line linguistically emphasizes gender as an illusory representation rather than a concrete reality. My adaptation of this scene as a drag performance echoes the sentiment that Shakespeare “writes people [not…] gender” (“Women Merely Players” 00:07:57-00:07:59) because his poetry calls attention to the performance of gender both on and off the stage. This aspect of Shakespeare’s poetry powerfully illustrates the danger of adhering to binary thinking as a society in which theatrical displays of gender performativity—and therefore fluidity—are ‘acceptable’ only because “the various conventions which announce that ‘this is only a play’ allows strict lines to be drawn between performance and life” (Butler 527). When gender fluidity is witnessed off-stage, it is met punitively (522) because it contests society’s gender essentialism that insists men and women are fundamentally different due to biological make up. Lady Macbeth’s personal tragedy stems from the fact that she views masculinity as biological, attempting to make it run in her blood (1.5.50) while telling her husband that his masculinity can only be achieved by performing ‘masculine’ acts like ambition-motivated murder. Because she acts gender herself, swapping between “actual performances” (5.1.13) of feminine hostess and masculine master, but only accepts gender as essential, she finds herself in an irreconcilable dilemma that erases her identity and confines her to the silent suffering woman trope by the end of the play.

In terms of dress, I decided that key garments—the breastplate, corset, and skirt—should be made separately, deliberately put onto the model after the body was painted to creatively embody the process of what feminist scholar Judith Butler calls “the crafting of gender.” Drag Lady Macbeth’s male body is made to be perceived as feminine via garments which produce a visual metaphor of womanliness. I painted the breastplate on a separate piece of paper and carefully cut out the gap for the neck to highlight its removability and its ability to portray a woman only if it is put on. This garment is reminiscent of Lady Macbeth’s metaphorical transformation of Macbeth’s “milk of human kindness” (1.5.17), a compassion just as nourishing as a mother’s milk, into the “gall” (1.5.55) of her female breasts. Next, I cut the corset out of a magazine cover and drew the ribbing onto it before pasting it on; this garment represents the suffocating restrictions of adhering to strict gender binaries which are “put on […] under constant constraint, daily and incessantly, with anxiety and pleasure” (Butler 531). This kind of breath-restricting anxiety can be seen in Macbeth’s alliterative response to his failed execution order of Banquo and his offspring, an act that would ‘prove’ his masculine ambition to his wife: “Then comes my fit again. I had else been perfect, / …. / But now I am cabined, cribbed, confined, bound in / To saucy doubts and fears” (3.4.23-27; emphasis mine). These fits of weakness provoke Lady Macbeth’s degrading taunts towards his masculinity, which ultimately results in Macbeth restricting himself to the extreme masculine archetype of cruel tyrant, callously saying that returning to morality is “as tedious as” (3.4.170) continuing his murder spree. The confining structure of the corset on drag Lady Macbeth represents the imposed gender restrictions which ultimately cause the Macbeths’ tragic downfall. Lastly, the hoop skirt—called a farthingale—was constructed by threading embroidery floss through the paper, tying each line segment individually on the back. This underskirt was significant in Elizabethan dress because it feminized one’s outward appearance by emphasizing the lower half of the body (Bendall 712, 716); I included it because it was the most intensive and exhausting to construct, emphasizing the laborious “stylization of the body” (Butler 519) necessary for upholding the punitive binary gender system.

The androgynous hands in my adaptation represent the non-binary witches in Macbeth, placed deliberately to illustrate the subversive power that can be harnessed when gender is understood as performative. Butler re-contextualizes gender as a scripted “act that has been going on before one arrived on the scene” (526) meaning that existing cultural understandings of gender expression are projected onto the body by others before its birth. This, in turn, informs its future gender act. I included the disembodied witch hands because I believe that the spirits Lady Macbeth invokes are the witches she has just read about in Macbeth’s letter. These androgynous witches, who appear prior to the “unsexing,” prompt Banquo to question which gender they represent based on their exterior: “You should be women, / And yet your beards forbid me to interpret / That you are so” (1.3.47-49). Banquo encounters the irreconcilable dilemma of gender essentialism being contested by the subversive genderless state that the witches inhabit, struggling to fit them into traditional categories. Two scenes later, Lady Macbeth is metaphorically influenced by the acting of gender that precedes her arrival on stage; she seems to invoke the subversive power of the witches asking them to “unsex” (1.5.48) her but cannot harness it because she continues to mistake gender “for a natural or linguistic given” (Butler 531) when she asks the spirits to rearrange her biological—essential— make-up (1.5.48, 50, 54-55) and assert her masculinity “with the valor of [her] tongue” (1.5.30). Thus, the hands in my adaptation exclusively manipulate external garments; one androgynous hand unties the corset—undoing the restrictive, feminizing garment—while others weave through the threads of the skirt in a ‘snipping’ gesture, emphasizing that the illusion of a ‘natural’ gender binary falls apart when its manufactured performance is highlighted. The placement of these hands demonstrates the wearing of gender by removing the gender costume from drag Lady Macbeth and suggest that the witches in the play provide the alternative reality to the (ultimately fatal) gendered world of Scotland.

The structural elements of my drag queen adaptation of Lady Macbeth offer insight into the construction, the putting on and performing of gender, by linking Shakespearean cross-gender theatre traditions to the contemporary drag industry. Simultaneously, the problem that arises when one essentializes and rigidifies gender rather than viewing it as a fluid exteriority— the dilemma which arguably proves fatal to the Macbeths and those around them—is illustrated as a loss of identity that strips a person of flexibility and thus the ability to thrive in changing conditions. The presence of the androgynous, aloof witches sits in contrast with the punitively gendered world of the Macbeths, suggesting that a world which exists beyond gender is one that fosters a sustainable and complete human existence.

Works Cited

Bendall, Sarah A. “‘Take Measure of Your Wide and Flaunting Garments’: The Farthingale, Gender and the Consumption of Space in Elizabethan and Jacobean England.” Renaissance Studies, vol. 33, no. 5, Nov. 2018, pp. 712–737, https://doi.org/10.1111/rest.12537.

Butler, Judith. “Performative Acts and Gender Constitution: An Essay in Phenomenology and Feminist Theory.” Theatre Journal, vol. 40, no. 4, 1988, pp. 519–531, https://doi.org/10.2307/3207893.

Shakespeare, William. The Tragedy of Macbeth. Edited by Barbara A. Mowat and Paul Werstine, Simon and Schuster Paperbacks, 2013.

Jacobsen, Naomi, et al. “Women Merely Players.” Shakespeare Unlimited, episode 2, The Folger Shakespeare Library, 15 March, 2017, www.folger.edu/shakespeare-unlimited/actresses-on-shakespeare.