Energy and Ecosystems

Key Concepts

After completing this chapter, you will be able to

- Describe the nature of energy, its various forms, and the laws that govern its transformations.

- Explain how Earth is a flow-through system for solar energy.

- Identify the three major components of Earth’s energy budget.

- Describe energy relationships within ecosystems, including the fixation of solar energy by primary producers and the passage of that fixed energy through other components of the ecosystem.

- Explain why the trophic structure of ecological productivity is pyramid-shaped and why ecosystems cannot support many top predators.

- Compare the feeding strategies of humans living a hunting and gathering lifestyle with those of modern urban people.

Introduction

None of planet Earth, its biosphere, or ecosystems at any scale are self-sustaining with respect to energy. In fact, without continuous access to an external source of energy, all of these entities would quickly deplete their stored energy, would rapidly cool, and in the case of the biosphere and ecosystems, would cease to function in ways that support life. The external source of energy those systems use is solar energy, which is stored mainly as heat and biomass. In effect, solar energy is absorbed by green plants and algae and is utilized to fix carbon dioxide and water into simple sugars through a process known as photosynthesis. This biological fixation of solar energy provides the energetic basis for almost all organisms and ecosystems (the few exceptions are described later). Energy is critical to the functioning of physical processes throughout the universe, and of ecological processes in the biosphere of Earth. In this chapter we will examine the physical nature of energy, the laws that govern its behaviour and transformations, and its role in ecosystems.

The Nature of Energy

Energy is a fundamental physical entity and is simply defined as the capacity of a body or system to accomplish work. In physics, work is defined as the result of a force being applied over a distance. In all of the following examples of work, energy is transformed and some measurable outcome is achieved:

- A hockey stick strikes a puck, causing it to speed toward a target

- A book is picked up from the floor, lifted, and then laid on a table

- A vehicle is driven along a road

- Heat from a stove is absorbed by water in a pan, eventually causing it to boil

- The photosynthetic pigment chlorophyll absorbs sunlight, converting the electromagnetic energy (light) into a form that plants and algae can use to synthesize sugars

Energy can exist in various states, each of which is fundamentally different from the others. However, under suitable conditions energy in any state can be converted into another one through physical or chemical transformations. The states of energy can be grouped into three categories: electromagnetic, kinetic, and potential.

Electromagnetic Energy

Electromagnetic energy (or electromagnetic radiation) is associated with photons. These have properties of both particles and waves and travel through space at a constant speed of 3 × 108 m/s (the speed of light). Electromagnetic energy exists as a continuous spectrum of wavelengths, which (ordered from the shortest to longest wavelengths) are known as gamma, X-ray, ultraviolet, visible light, infrared, microwave, and radio (Figure 4.1). The human eye can perceive electromagnetic energy over a range of wavelengths of about 0.4 to 0.7 μm, a part of the spectrum that is referred to as visible radiation or light (1 μm, or 1 micrometre, is 10–6 m; see Appendix A).

Figure 4.1. The Electromagnetic Spectrum. The spectrum is divided into major regions on the basis of wavelength and is presented on a logarithmic scale (log10) in units of micrometres (1 µm = 10–3mm = 10–6 m). Note the expansion of the visible component and the wavelength ranges for red, orange, yellow, green, blue, and violet colours.

Electromagnetic energy is given off (or radiated) by all objects that have a surface temperature greater than absolute zero (greater than -273°C or 0°K). The surface temperature of a body determines the rate and spectral quality of the radiation it emits. Compared with a cooler body, a hotter one has a much larger rate of emission, and the radiation is dominated by shorter, higher-energy wavelengths. For example, the Sun has an extremely hot surface temperature of about 6000°C, and as a direct consequence, most of the radiation it emits is ultraviolet (0.2 to 0.4 μm), visible (0.4 to 0.7 μm), and near infrared (0.7 to 2 μm). (Note that the interior of the Sun is much hotter than 6000°C, but it is the surface temperature that directly influences the emitted radiation). Because the surface temperature of Earth averages much cooler at about 15°C, it radiates much smaller amounts of energy at longer wavelengths (peaking at a wavelength of about 10 μm).

Image 4.1. The energy of the Sun is derived from nuclear fusion reactions involving hydrogen nuclei. These reactions generate enormous quantities of thermal and electromagnetic energy. Solar electromagnetic radiation is the most crucial source of energy that sustains ecological and biological processes. Source: NASA image: http://sdo.gsfc.nasa.gov/assets/img/latest/latest_4096_0304.jpg

Kinetic Energy

Kinetic energy is associated with bodies that are in motion. Two classes of kinetic energy can be distinguished.

Mechanical kinetic energy is associated with any object that is in motion, meaning it is travelling from one place to another. For example, a hockey puck flying through the air, a trail-bike being ridden along a path, a deer running through a forest, water flowing in a stream, or a planet moving through space are all expressions of this kind of kinetic energy. The amount of mechanical kinetic energy is determined by the mass of an object and its speed.

Thermal kinetic energy is associated with the rate that atoms or molecules are vibrating. Such vibrations cease (are frozen) at -273°C (absolute zero), but are progressively more vigorous at higher temperatures, corresponding to a larger content of thermal kinetic energy, which is also referred to as heat.

Potential Energy

Potential energy is the stored ability to perform work. To actually perform work, potential energy must be transformed into electromagnetic or kinetic energy. There are a number of kinds of potential energy:

Gravitational potential energy results from gravity, or the attractive forces that exist among all objects. For example, water stored at any height above sea level contains gravitational potential energy. This can be converted into kinetic energy if there is a pathway that allows the water to flow downhill. Gravitational potential energy can be converted into electrical energy through the technology of hydroelectric power plants.

Chemical potential energy is stored in the bonds between atoms within molecules. Chemical potential energy can be liberated by exothermic reactions (those which lead to a net release of thermal energy, such as fire), as in the following examples:

- Chemical potential energy is stored in the molecular bonds of sulphide minerals, such as iron sulphide (FeS2), and some of this energy is released when the sulphides are oxidized. Specialized bacteria can metabolically tap the potential energy of sulphides to support their own productivity, through a process known as chemosynthesis (this is further examined later in this chapter).

- The ionic bonds of salts also store chemical potential energy. For example, when sodium chloride (table salt, NaCl) is dissolved in water, ionic potential energy is released as heat, which slightly increases the water temperature.

- Hydrocarbons store energy in the bonds between their hydrogen and carbon atoms (hydrocarbons contain only these atoms). The chemical potential energy of gasoline, a mixture of liquid hydrocarbons, is liberated in an internal combustion engine and becomes mechanically transformed to achieve the kinetic energy of vehicular motion.

- Organic compounds (biochemicals) produced metabolically by organisms also store large quantities of potential energy in their inter-atomic bonds. The typical energy density of carbohydrates is about 16.8 kJ/g, while that of proteins is 21.0 kJ/g, and lipids (or fats) 38.5 kJ/g. Many organisms store their energy reserves as fat because these biochemicals have such a high energy density.

Electrical potential energy results from differences in the quantity of electrons, which are subatomic, negatively charged particles that flow from areas of high density to areas where it is lower. When an electrical switch is used to complete a circuit connecting two areas with different electrical potentials, electrons flow along the electron gradient. The electric energy may then be transformed into uses such as light, heat, or work performed by a machine (e.g. an electric motor). A difference in electrical potential is known as voltage, and the current of electrons must flow through a conducting material, such as a metal.

Elasticity is a kind of potential energy that is inherent in the physical qualities of certain flexible materials and that can perform work when released, as occurs when a drawn bow is used to shoot an arrow.

Compressed gases also store potential energy, which can do work if expansion is allowed to occur. This type of potential energy is present in a cylinder containing compressed or liquefied gas. It is also showing some real potential in storing energy from renewable energy sources.

Nuclear potential energy results from the extremely strong binding forces that exist within atoms. This is by far the densest form of energy. Huge quantities of electromagnetic and kinetic energy are released when nuclear reactions convert matter into energy. A fission reaction involves the splitting of isotopes of certain heavy atoms, such as uranium-235 and plutonium-239 (U235 and 239P), to generate smaller atoms plus enormous amounts of energy. Fission reactions occur in nuclear explosions and, under controlled conditions, in nuclear reactors used to generate electricity. A fusion reaction involves the combining of certain light elements, such as hydrogen, to form heavier atoms under conditions of extremely high temperature and pressure, while liberating huge quantities of energy. Fusion reactions involving hydrogen occur in stars and are responsible for the unimaginably large amounts of energy that these celestial bodies generate and radiate into space. It is thought that all heavy atoms in the universe were produced by fusion reactions occurring in stars. Fusion reactions also occur in a type of nuclear explosive device known as a hydrogen bomb. A technology has not yet been developed to exploit controlled fusion reactions to generate electricity; if and when available, controlled fusion could be used to generate virtually unlimited amounts of commercial energy.

Image 4.2. Organic matter and fossil fuels contain potential chemical energy, which is released during combustion to generate heat and electromagnetic radiation. This forest fire was ignited by lightning and burned the organic matter of a pine forest. Source: NASA image: Kari Greer, http://www.nasa.gov/images/content/710937main_climate-fire-lg.jpg

Earth: An Energy Flow-Through System

Electromagnetic radiation emitted by the Sun is by far the major input of energy that drives ecosystems. Solar energy heats the planet, circulates its atmosphere and oceans, evaporates its water, and sustains almost all its ecological productivity. Eventually, all of the solar energy absorbed by Earth is re-radiated back to space in the form of electromagnetic radiation of a longer wavelength than what was originally captured. In other words, Earth is a flow-through system, with a perfect balance between the input of solar energy and output of re-radiated energy, and no net storage over the longer term.

In addition, almost all ecosystems absolutely depend on solar radiation as the source of energy that photosynthetic organisms (such as plants and algae) utilize to synthesize simple organic compounds (such as sugars) from inorganic molecules (carbon dioxide and water). Plants and algae then use the chemical potential energy in these sugars, plus inorganic nutrients (such as nitrate and phosphate), to synthesize a huge diversity of biochemicals through various metabolic reactions. Plants grow and reproduce by using the energy in these biochemicals. Moreover, plant biomass is used as food by the enormous numbers of organisms that are incapable of photosynthesis. These organisms include herbivores that eat plants directly, carnivores that eat other animals, and detritivores that feed on dead biomass. (The energy relationships within ecosystems are described later.)

Less than 0.02% of the solar energy received at Earth’s surface is absorbed and fixed by photosynthetic plants and algae. Although this represents a quantitatively trivial component of the planet’s energy budget, it is extremely important qualitatively because this biologically absorbed and fixed energy is the foundation of ecological productivity. Ultimately and eventually, however, the solar energy fixed by plants and algae is released to the environment again as heat and is eventually radiated back to outer space. This reinforces the idea of Earth being a flow-through system for energy, with a perfect balance between the input and output.

Earth’s Energy Budget

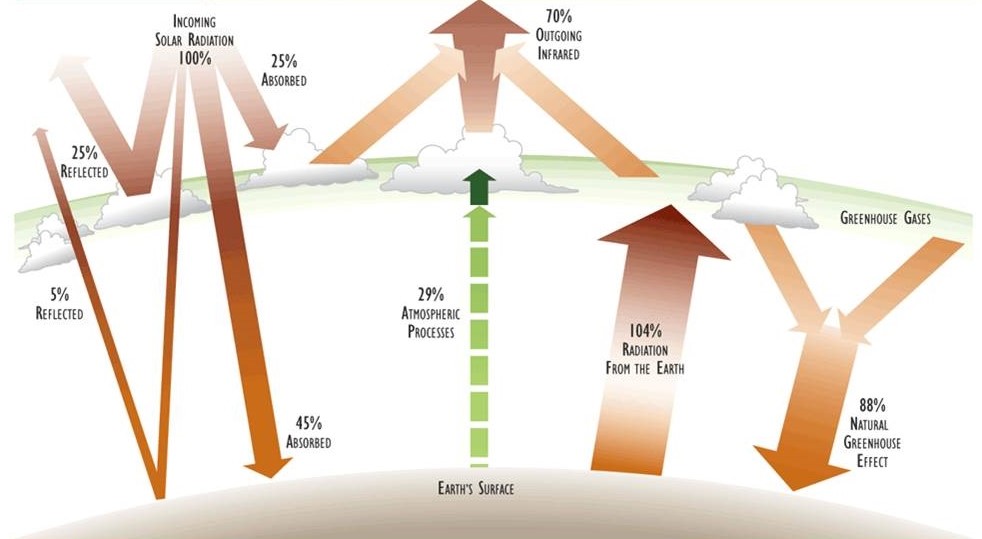

An energy budget of a system describes the rates of energy input and output as well as any internal transformations among its various states, including changes in stored quantities. Figure 4.2 illustrates key aspects of the physical energy budget of Earth.

The rate of input of solar radiation to Earth averages about 8.36 J/cm2-minute (2.00 cal/cm2-min), measured at the outer limit of the atmosphere. About half of this energy input is visible radiation and half is near infrared. The output of energy from Earth is also about 8.36 J/cm2-min, occurring as longer-wave infrared. Because the rates of energy input and output are equal, there is no net storage of energy, and the average surface temperature of the planet remains stable. Therefore, as was previously noted, the energy budget of Earth can be characterized as a zero-sum, flow-through system.

However, the above is not exactly true. Over extremely long scales of geological time, a small amount of storage of solar energy has occurred through an accumulation of un-decomposed biomass that eventually transformed into fossil fuels. In addition, relatively minor long-term fluctuations in Earth’s surface temperature occur, representing an important element of climate change. Nevertheless, the statement that Earth is a zero-sum, flow-through system for solar energy is generally true in almost all circumstances.

Figure 4.2. Important Components of Earth’s Physical Energy Budget. About 30% of the incoming solar radiation is reflected by atmospheric clouds and particulates and by the surface of the planet. The remaining 70% is absorbed and then dissipated in various ways. Much of the absorbed energy heats the atmosphere and terrestrial surfaces, and most is then re-radiated as long-wave infrared radiation. Atmospheric moisture and greenhouse gases interfere with this process of re-radiation, keeping the surface considerably warmer than it would otherwise be (see also Chapter 17). The numbers refer to the percentage of incoming solar radiation. See the text for a more detailed description of important factors in this energy budget. Source: Modified from Schneider (1989).

Even though the amount of energy emitted by Earth eventually equals the quantity of solar radiation that is absorbed, many ecologically important transformations occur between the initial absorption and eventual re-radiation. These are the internal elements of the physical energy budget of the planet (see Figure 4.2). The most important components are described below:

Reflection – On average, Earth’s atmosphere and surface reflect about 30% of incoming solar energy back to outer space. Earth’s reflectivity (albedo) is influenced by such factors as the angle of the incoming solar radiation (which varies during the day and over the year), the amounts of reflective cloud cover and atmospheric particulates (also highly variable), and the character of the surface, especially the types and amounts of water (including snow and ice) and darker vegetation.

Absorption by the Atmosphere – About 25% of incident solar radiation is absorbed by gases, vapours, and particulates in the atmosphere, including clouds. The rate of absorption is wavelength-specific, with portions of the infrared range being intensively absorbed by the so-called “greenhouse” gases (especially water vapour and carbon dioxide). The absorbed energy is converted to heat and re-radiated as infrared radiation of a longer wavelength than what has been initially absorbed.

Absorption by the Surface – On average, about 45% of incoming solar radiation passes through the atmosphere and is absorbed at Earth’s surface by living and non-living materials, a transformation that increases their temperature. However, this figure of 45% is highly variable, depending partly on atmospheric conditions, especially cloud cover, and also on whether the incident light has passed through a plant canopy. Although over the longer term (years) and even the medium term (days) the global net storage of heat is essentially zero, in some places there may be substantial changes in the net storage of thermal energy within the year. This occurs everywhere in Canada because of the seasonality of its climate, in that environments are much warmer during the summer than in the winter. Nevertheless, almost all of the absorbed energy is eventually dissipated by re-radiation from the surface as long-wave infrared.

Evaporation of Water – Some of the thermal energy of living and non-living surfaces causes water to evaporate in a process known as evapotranspiration. This process has two components: the evaporation of water from lakes, rivers, streams, moist rocks, soil, and other non-living substrates, and transpiration of water from any living surface, particularly from plant foliage, but also from moist body surfaces and lungs of animals.

Melting of Snow and Ice – Absorbed thermal energy can also cause ice and snow to melt, representing an energy transformation associated with a change of state of water from a solid to a liquid form.

Wind and Water Currents – There is a highly uneven distribution of the content of thermal energy at and near the surface of Earth, with some regions being quite cold (such as the Arctic) and others much warmer (the tropics). Because of this irregular allocation of heat, the surface develops processes to diminish the energy gradients by transporting mass around the globe, such as by winds and oceanic currents.

Biological Fixation – A very small but ecologically critical portion of incoming solar radiation (globally averaging less than 0.02%) is absorbed by chlorophyll in plants and algae and used to drive photosynthesis. This biological fixation allows some of the solar energy to be temporarily stored as potential energy in biochemicals, thereby serving as the energetic basis for ecological productivity and life on Earth.

Energy in Ecosystems

An ecological energy budget focuses on the absorption of energy by photosynthetic organisms and the transfer of that fixed energy through the trophic levels of ecosystems (“trophic” refers to the means of organic nutrition). Ecologists classify organisms in terms of the sources of energy they utilize.

Autotrophs are capable of synthesizing their complex biochemicals using simple inorganic compounds and an external source of energy to drive the process. The great majority are photoautotrophs, which use sunlight as their external source of energy. Photoautotrophs capture solar radiation using photosynthetic pigments, the most important of which is chlorophyll. Green plants are the most abundant examples of photoautotrophs, but algae and some bacteria are also photoautotrophic.

A much smaller number of autotrophs are chemoautotrophs, which harness some of the energy content of certain inorganic chemicals to drive a process called chemosynthesis. The bacterium Thiobacillus thiooxidans, for example, oxidizes sulphide minerals to sulphate and uses some of the energy released during this reaction to chemosynthesize organic molecules.

Because autotrophs are the biological foundation of ecological productivity, ecologists refer to them as primary producers. The total fixation of solar energy by all of the primary producers within an ecosystem is known as gross primary production (GPP). Primary producers use some of this production for their own respiration (R) – that is, for the physiological functions needed to maintain their health and to grow. Respiration is the metabolic oxidation of biochemicals, and it requires a supply of oxygen and releases carbon dioxide and water as waste products. Net primary production (NPP) refers to the fraction of GPP that remains after primary producers have used some for their own respiration. In other words: NPP = GPP – R.

The energy fixed by primary producers is the basis for the productivity of all other organisms, known as heterotrophs, which rely on other organisms, living or dead, to supply the energy they need. Animal heterotrophs that feed on plants are known as herbivores (or primary consumers); three familiar examples are deer, geese, and grasshoppers. Heterotrophs that consume other animals are known as carnivores (or secondary consumers), such as timber wolf, peregrine falcon, sharks, and spiders. Some species feed on both plant and animal biomass and are known as omnivores – the grizzly bear is a good example, as is our own species. Many other heterotrophs feed primarily on dead organic matter and are called decomposers or detritivores, such as vultures, earthworms, and most fungi and bacteria.

Image 4.3. Plant productivity is sustained by solar energy, which is fixed by chlorophyll in the plant and used to combine carbon dioxide, water, and other simple inorganic compounds into the complex molecular structures of organic matter. These ecologists are studying the productivity of a plant community on Sable Island, Nova Scotia. Source: B. Freedman.

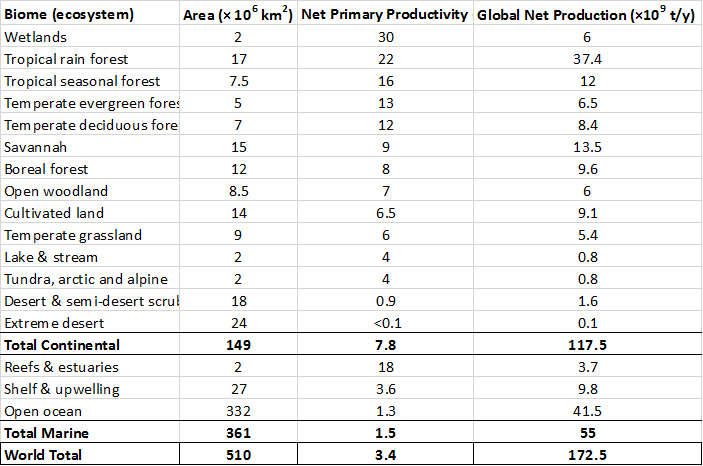

Productivity is production expressed as a rate function, that is, per unit of time and area. The primary productivities of the world’s major classes of ecosystems are summarized in Table 4.1. Note that the rate of production is greatest in tropical forests, wetlands, coral reefs, and estuaries. The production for each ecosystem type is calculated as its productivity multiplied by its area. However, the largest amounts of production occur in tropical forests and the open ocean. Note that the open ocean has a relatively small productivity, but its global production is large because of its enormous area.

Table 4.1. Primary Production of Earth’s Major Ecosystems. The ecosystems are listed in order of net primary productivity. Productivity is the rate of production, standardized to area and time, while production is the total amount of biomass (in dry tonnes) produced by the global area of an ecosystem. See Chapter 8 for descriptions of these biomes (major kinds of ecosystems). Source: modified from Whittaker and Likens (1975).

An ecological food chain is a linear model of feeding relationships among species. An example of a simple food chain in northern Canada is lichens and sedges, which are eaten by caribou, which are eaten by wolves. A food web is a more complex model of feeding relationships, because it describes the connections among all food chains within an ecosystem. Wolves, for instance, are opportunistic predators that may feed on snowshoe hare, voles, lemming, beaver, birds, and other prey in addition to their usual prey of deer, moose, and caribou. Therefore, wolves participate in various food chains within their ecosystem. However, no natural predators feed on wolves, which are therefore referred to as top carnivores or top predators.

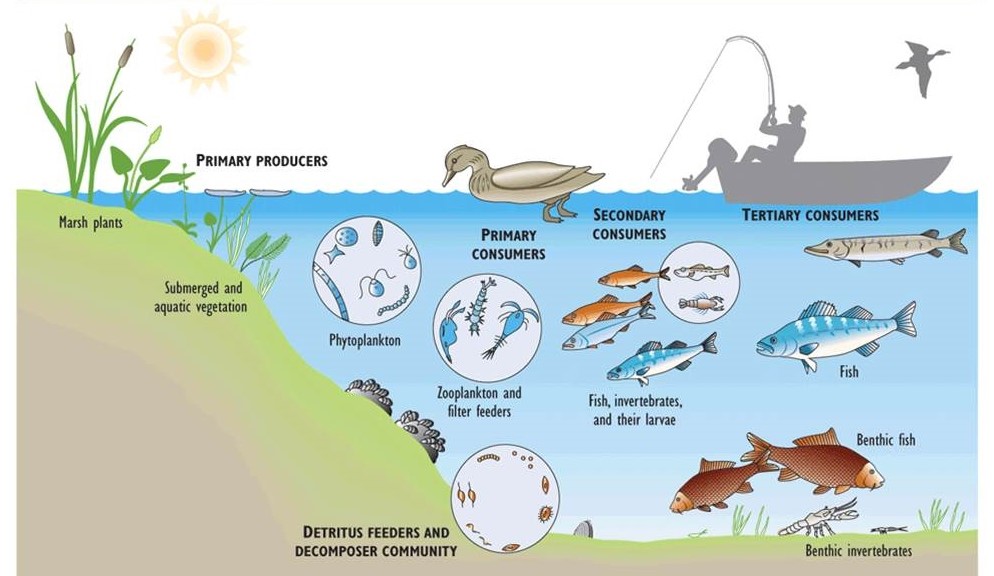

Figure 4.3 illustrates important elements of the food web of Lake Erie, one of the Great Lakes. In this large lake, shallow-water environments support aquatic plants, while phytoplankton occur throughout the upper water column. The shallow-water plants are consumed by ducks, muskrat, and other herbivores, while phytoplankton are consumed by tiny crustaceans (zooplankton) and bottom-living filter-feeders such as clams. Zooplankton are eaten by small fish such as smelt, which are eaten by larger fish, which may eventually be eaten by cormorants, bald eagles, or humans. Dead biomass from any level of the food web may settle to the bottom, where it enters a detrital food web and is eaten by small animals and ultimately decomposed by bacteria and fungi.

Figure 4.3. Major Elements of the Food Web in Lake Erie. Food webs are complex systems, involving many species and various food chains.

In accordance with the second law of thermodynamics, the transfer of energy in food webs is always inefficient because some of the fixed energy must be converted into heat. For example, when a herbivore consumes plant biomass, only some of the energy content can be assimilated and transformed into its biomass. The rest is excreted in feces or utilized in respiration (Figure 4.4). Consequently, in all ecosystems the amount of productivity by autotrophs is always much greater than that of herbivores, which in turn is always much greater than that of their predators. As a broad generalization, there is about a 90% loss of energy at each transfer stage. In other words, the productivity of herbivores is only about 10% of that of their plant food, and the productivity of the first carnivore level is only 10% of that of the herbivores they feed upon.

Figure 4.4. Model of Energy Transfer in an Ecosystem. Lower levels of a food web always have a greater production than higher levels. For this reason, the trophic structure is roughly pyramidal. According to the second law of thermodynamics, some of the energy content in food webs is converted into heat or respiration (R). There is about a 90% loss of energy at each transfer stage.

These productivity relationships can be displayed graphically using a so-called ecological pyramid to represent the trophic structure of an ecosystem. Ecological pyramids are organized with plant productivity on the bottom, that of herbivores above the plants, and carnivores above the herbivores. If the ecosystem sustains top carnivores, they are represented at the apex of the pyramid. The sizes of the trophic boxes in Figure 4.4 suggest the pyramid-shaped structure of ecosystem productivity.

The second law of thermodynamics applies to ecological productivity, a function that is directly related to energy flow. The second law does not, however, directly explain the accumulated biomass of an ecosystem. Consequently, it is only the trophic structure of productivity that is always pyramid-shaped. In some ecosystems, other variables may have a pyramid-shaped trophic structure, such as the amounts of biomass (standing crop) present at specific times, or the sizes or densities of populations. However, these particular variables are not pyramid-shaped in all ecosystems.

For example, in the open ocean, phytoplankton are the primary producers, but they often maintain a biomass similar to that of the small zooplankton that feed upon them. The phytoplankton cells are relatively short-lived, and their biomass turns over quickly because of their high rates of productivity and mortality. In contrast, the individual zooplankton animals are longer-lived and much less productive than the phytoplankton. Consequently, the productivity of the phytoplankton is much larger than that of the zooplankton, even though at any particular time these trophic levels may have a similar biomass.

Some ecosystems may even have an inverted pyramid of biomass, characterized by a smaller biomass of plants than of herbivores. This sometimes occurs in grasslands, in which the dominant plants are relatively small herbaceous species that can be quite productive but do not maintain a large biomass. In comparison, some of the herbivores that feed on the plants are large, long-lived animals, which may maintain a greater total biomass than the vegetation. Some temperate and tropical grasslands have an inverted biomass pyramid, especially during the dry season when there may be large populations (and biomass) of long-lived herbivores such as antelope, bison, deer, elephant, gazelle, hippopotamus, or rhino. However, in accordance with the second law of thermodynamics, the annual (or long-term) productivity of the plants in these grasslands is always much larger than that of the herbivores.

In addition, the population densities of animals are not necessarily smaller than those of the plants that they eat. For instance, insects are the most important herbivores in many forests and they commonly maintain large populations. In contrast, the numbers of trees are much smaller, because each individual plant is large and occupies a great deal of space. Forests typically maintain many more herbivores than trees and other plants, so the pyramid of numbers is inverted in shape. As in all ecosystems, however, the pyramid of forest productivity is much wider at the bottom than at the top.

Because of the inefficiency of the energy transfer between trophic levels, there are energetic limits to the numbers of top carnivores (such as eagles, killer whales, sharks, and wolves) that can be sustained by an ecosystem. To sustain a viable population of top predators, there must be a suitably large production of prey that these animals can exploit. This prey must in turn be sustained by an appropriately high plant productivity. Because of these ecological constraints, only extremely productive or very extensive ecosystems can support top predators. Of all Earth’s terrestrial ecosystems, none supports more species of higher-order carnivores than the savannahs and grasslands of Africa. The most prominent of these top predators are the cheetah, hyena, leopard, lion, and wild dog. This unusually high richness of top predators can be sustained because these African ecosystems are immense and quite productive of vegetation, except during years of drought. In contrast, the tundra of northern Canada can support only one natural species of top predator, the wolf. Although the tundra is an extensive biome, it is a relatively unproductive ecosystem.

Some pre-industrial human populations functioned as top predators. This included certain Aboriginal peoples of Canada, such as the Inuit of the Arctic and many First Nations cultures of the boreal forest. As an ecological consequence of their higher-order feeding strategy within their food web, these cultures were not able to maintain large populations. In most modern economies, however, humans interact with ecosystems in an omnivorous manner—we harvest an extremely wide range of foods and other biomass products of microbes, fungi, algae, plants, and invertebrate and vertebrate animals. One of the consequences of this kind of feeding is that a large human population can be sustained.

Enviromental Issues 4.1. Vegetarianism and Energy Efficiency

Most people have an omnivorous diet, meaning they eat a wide variety of foods of both plant and animal origin. Vegetarians, however, do not eat meat or other foods produced by killing birds, fish, mammals, or other animals. Some vegetarians, known as vegans, do not eat any foods of animal origin, including cheese, eggs, honey, or milk. People may choose to adopt a vegetarian lifestyle for various reasons, including those that focus on the ethics of the rearing and slaughter of animals and the health benefits of a balanced diet that does not include animal products. In addition, there are large environmental benefits of vegetarianism. They are dues to avoiding certain air, water, and soil pollutants, and reducing the conversion of natural habitat into agroecosystems used for livestock rearing. In addition, it takes much less energy to feed a population of vegetarian humans than omnivorous ones.Cultivated animals eat a great deal of food. In the industrial agriculture practised in developed countries, including Canada, livestock are raised mostly on a diet of plant products, including cultivated grain. Some vegetarians argue that if that grain were fed directly to people, the total amounts of cereals and agricultural land needed to support the human population would be much less. This argument is based on the inefficiency of energy transfer between trophic levels, which we examined in this chapter in a more ecological context. This energy-efficiency argument is most compelling for animals that are fed on grain and other concentrated foods. It is less relevant to livestock that spend all or part of their life grazing on wild rangeland – in that ecological context, ruminant animals such as cows and sheep are eating plant biomass that humans could not directly consume and so they are producing food that would not otherwise be available.

Similarly, many chickens, pigs, and other livestock are fed food wastes (for example, from restaurants) and processing by-products (such as vegetable and fruit culls and peelings, and grain mash from breweries) that are not suitable for human consumption. It has been estimated that about 25% of global cropland is being used to grow grain and other foods for livestock, and that 37% of the world’s cereal production is fed to agricultural animals. In North America, however, about 70% of the grain production is fed to livestock. And there are immense numbers of agricultural animals: globally, there are more than 3 billion cows, goats, and sheep, and at least 20 billion chickens. The cows alone eat the equivalent of the caloric needs of 8–9 billion people.

Assimilation efficiency is a measure of the percentage of the energy content of an ingested food that is absorbed by the gut and therefore available to support the metabolic needs of an animal. This efficiency varies among groups of animals and also depends on the type of food being eaten. Herbivorous animals typically have an assimilation efficiency of 20–50%, with the smaller rate being for tough, fibrous, poor-quality foods such as grass and straw, and the larger one for higher-quality foods such as grain. Carnivores have a higher assimilation efficiency, around 80%, because their food is so dense in protein and fat. Overall, it takes about 16 kg of feed to produce 1 kg of beef in a feedlot. The ratios for other livestock are 6:1 for pork, 3:1 for chicken, and 2:1 to 3:1 for farmed fish. These assimilation inefficiencies would be avoided if people directly ate the grain consumed by livestock, however this is a complex equation that will be explored more later in the book.

Ecological energetics is not the only consideration in the energy efficiency of vegetarianism. Huge amounts of energy are also used to convert natural ecosystems into farmland, to cultivate and manage the agroecosystems, to transport commodities, to process and package foods, and to transport, treat, or dispose of waste materials. These energy expenditures would also potentially be substantially reduced if more people had a vegetarian diet and lifestyle. Vegetarians are regarded by some as having a smaller “ecological footprint” associated with their feeding habits.

Conclusions

Energy can exist in various states, but transformations from one to another must obey the laws of thermodynamics. Organisms and ecosystems would spontaneously degrade if they did not have continuous access to external sources of energy. Ultimately, sunlight is the key source of energy that supports almost all life and ecosystems. Sunlight is used by photoautotrophs to combine carbon dioxide and water into simple organic molecules through the metabolic process of photosynthesis. The fixed energy of plant biomass supports ecological food webs. Plants may be eaten by herbivores and the energy obtained is used to support their own growth. Herbivores may then be eaten by carnivores. Dead biomass supports a decomposer food web. Sunlight also drives important planetary functions, such as the hydrologic and climatic systems. Human activities can have a large and degrading influence on food webs, and even on Earth’s climatic system by influencing the intensity of the planet’s greenhouse effect.

Questions for Review

- What forms of energy are described in this chapter? How can each be changed into other forms?

- What are the major elements of Earth’s physical energy budget?

- Why is the trophic structure of ecological productivity pyramid-shaped?

Questions for Discussion

- According to the second law of thermodynamics, systems always spontaneously move toward a condition of greater entropy. Yet life and ecosystems on Earth represent local systems where negative entropy is continuously being generated. What conditions allow this apparent paradox to exist?

- Why are there no natural higher-order predators that kill and eat lions, wolves, and sharks?

- Why would it be more efficient for people to be vegetarian? Discuss your answer in view of the pyramid-shaped structure of ecological productivity.

- Make a list of the key sources and transformations of energy that support you and your activities on a typical day. What is the ultimate source of each of the energy resources you use (such as sunlight and fossil fuels)?

Exploring Issues

- As part of a study of the cycling of pollutants, you have been asked to describe the food web of two local ecosystems. One of the ecosystems is a natural forest (or prairie) and the other is an area used to grow wheat (or another crop). How would you determine the major components of the food webs of these ecosystems, the species occurring in their trophic levels, and the interactions among the various species that are present?

References Cited and Further Reading

Botkin, D.B. and E.A. Keller. 2014. Environmental Science: Earth as a Living Planet. 9th ed. Wiley & Sons, New York, NY.

Freedman, B. 1995. Environmental Ecology. 2nd ed. Academic Press, San Diego, CA. Gates, D.M. 1985. Energy and Ecology. Sinauer, New York, NY.

Hinrichs, R.A. and M. Kleinbach. 2012. Energy: Its Use and the Environment. 5th ed. Brook Cole, Florence, KY.

Houghton, J.T. 2009. Global Warming. The Complete Briefing, 4th ed. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK.

Odum, E.P. 1993. Basic Ecology. Saunders College Publishing, New York, NY

Liu, P.I. 2009. Introduction to Energy, Technology, and the Environment. 2nd ed. ASME Press, New York, NY.

Priest, J. 2012. Energy: Principles, Problems, Alternatives. 8th ed. Kendall Hunt Publishing Co., Dubuque, IO.

Schneider, S.H. 1989. The Changing Climate. Scientific American, 261(3): 70-9

Whittaker, R.H. and G.E. Likens. 1975. The Biosphere and Man. pp. 305-28. In: Primary Productivity of the Biosphere. (H. Lieth and R.H. Whittaker, eds.). Springer-Verlag, New York, NY.