20 Safe Sport in Parasport: Imitating Society’s Imbalances

Jeff Tiessen

Maureen Connolly

Themes

Equity and Inclusion

Parasport

Disability

Learning Objectives

When you have completed this chapter, you will be able to:

LO1 Identify four challenges in translating universal safe sport policies and procedures to safe sport in parasport practice;

LO2 Explain how ableism impacts safe sport in parasport;

LO3 Describe how unconscious bias impacts safe sport in parasport;

LO4 Understand the importance of disability culture and language to safe sport in parasport; and

LO5 Employ three strategies for representation of inclusive values, education and lived experience in safe sport in parasport.

Overview

Drawing upon anecdotal evidence and author-lived experience as a three-time Paralympian, parasport administrator, and disability subject-matter expert and educator, and years of research and practice as a scholar, national award-winning teacher, and activist, this chapter presents the challenges confronting the vision of universal safe sport with respect to its translation and implementation for equity-deserving parasport athletes.

With prevailing societal constructs such as ableism and implicit unconscious bias toward athletes with disabilities equally present in the sport sector, this chapter proposes that pillars of education, authentic representation, and allyship are foundational to attaining meaningful safe sport in parasport.

Key Dates

Introduction to Safe Sport in Parasport

Disability is complicated. People with the same type or level of embodied complexity such as amputation, spinal cord injury, intellectual disability, or vision or hearing loss for examples, may identify with, and manage, the experience of disability in very different ways. Add intersectionality and multi-culturalism as parts of those identities and the experience of disability becomes even more nuanced.

The directory of disability categories continues to grow as episodic and chronic conditions are added. Episodic disability experience, like arthritis and diabetes, is a recognized newcomer, as are chronic health conditions like asthma, persistent pain and fatigue. Some people consider their neurodiversity, such as autism, ADHD, or dyslexia for examples, to be a disability diagnosis while others consider these differences to be strengths.

Hence, in the complexity of diversity and fragmentation of the disability community, safe sport for parasport is not easily translated or transposed from prescriptive policies and procedures, particularly when those policies and procedures are scripted for typical athletes. safe sport in parasport may find its pathway to effective implementation in the form of an over-arching objective of allyship.

In the News:

Safeguarding in Parasport

“Western University researchers want to learn more about safe sport policies for para athletes” By Isha Bhargava, CBC News, May 16, 2023.

Western University in London, ON, is launching a study to explore the protections in place for athletes in parasports, and the effectiveness of those safeguarding practices. The study will look at the experiences of para-athletes, what they believe can help them feel supported, and what is missing in these conversations.

Karmen Mohindru, a graduate student doing the study alongside her professor P. David Howe, noted:

Athletes’ voices within these policies are lacking and it’s incredibly important that… we have them be part of the conversation … It shouldn’t be their responsibility to police it, but we should get their insight on what would make for a safer environment and what they view as gaps in the policy.[1]

Understanding the Evolution of Disability Culture: Models of Disability

An introduction to models of disability illustrates how the disability community is evolving away from the idea of broken bodies and moving toward embracing differences, culturally and with pride. Colin Cameron, Danielle Peers, and Dan Goodley offer background and context on these models.[2]

Figure 20.1 – Medical Model of Disability

Now mostly outdated, the Individual or Medical Model of Disability (see Figure 20.1) views disability as something that is “wrong” with the person. It suggests the “impairment” is a problem to be fixed. Key criticism of this model is that “fixing” is not an appropriate response to disability. Disability is a part of our human condition.[3]

Figure 20.2 – Social Model of Disability

More contemporary, the Social Model of Disability (see Figure 20.2) views disability as something that exists because of physical and attitudinal barriers in society. The criticism of this model is that a fully barrier-free society for all is not possible. No amount of social change negates the embodied realities and complexities of impairment. That said, it is the case that much disablement is based in the failure or unwillingness to accommodate or adapt to embodied complexity.[4]

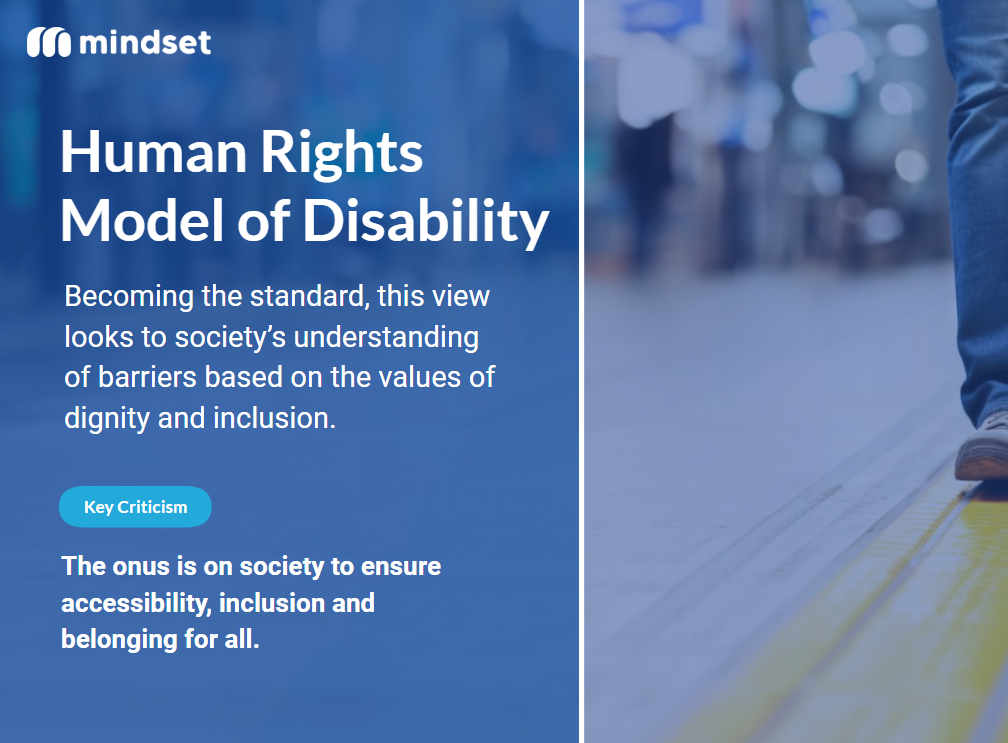

Figure 20.3 – Human Rights Model of Disability

Human Rights and Critical/Social Justice Models of Disability (see Figure 20.3) are becoming the standard. These models attempt to approach barriers and assumptions associated with disability based on the values of dignity and inclusion. The challenge, however, is that the onus is often on legislative, organizational, and policy-based initiatives to ensure accessibility, inclusion and belonging for all.[5]

Therein lies the challenge for safe sport in parasport.

Society, often unintentionally, perpetuates ableism, unconscious bias, and inspirational objectification.[6] These challenges are not rinsed away in the discussion of safe sport in parasport. In fact, in some ways they are being extended by policies and procedures that have not been informed by, or created in partnership with, disability communities.

The Canadian Paralympic Committee (CPC) is a nonprofit organization that strives to “leverage the unique and profound impact of Paralympic sport as a tool for societal change.”[7] The CPC believes that everyone involved in sport has the right to participate in a safe and inclusive environment that is free of all forms of maltreatment. The organization is a member of the Canadian Safe Sport Program.

Ableism in its Four Forms

Communicating to an athlete that they “don’t look disabled,” while intended to be a compliment, can prompt that athlete to feel as if the onus is on them to prove their disability. Asking an athlete “what’s wrong” with them or “what happened” to them inherently presumes that the differences that disabled people live with are deficits that need to be fixed. “You are so inspirational,” is a common and well-intentioned comment that can objectify an athlete with a disability when associated with mundane or less-than-extraordinary athletic achievement. Ableism may not be readily visible, but it can be easily felt.[8]

Ableism in sport, like ableism in any “walk of life,” is social prejudice, rooted in the belief that typical abilities are best. Ableism creates stigma, bias and stereotypes. And it leaves an indelible mark. When one individual is favoured over another for what is considered “normal” or able in body form, this preference, or lack thereof, can foster self-doubt, uncertainty and insecurity. The resulting emotional toll can be debilitating for those who do not present as typical or “normal” by societal standards.[9]

Danielle Peers and Maureen Connolly, among other disability studies scholars, write about different presentations of ableism.[10] Ableism is a system of beliefs that favours and privileges non-disabled bodies as normal or ideal and can make its presence known in four different ways:

Enlightened Ableism: When someone talks a good game about inclusion and equality for people experiencing disability but persists with practices that marginalize and stereotype. Although it is not intentional, it still perpetuates the notion of lesser than, and not equal.

Unconscious Ableism: When someone is unaware that what they are saying or doing is insensitive and marginalizes and stereotypes disabled persons.

Mundane Ableism: When someone is not interested in understanding that what they are routinely saying or doing is offensive and marginalizes and stereotypes.

Disableism: This is the belief that people with a disability are inferior. Where ableism favours “able-bodied” people and prioritizes the needs of people without disabilities, disableism is discrimination against people with disability. Ableism views disabled people as less than… less valuable, less able to contribute. Ableism can be conscious or unconscious. Ableism limits opportunities for people disabilities and limits inclusion. Disableism discriminates, not unlike discrimination in the form of racism or sexism.

With ableism present as the prevailing belief system in sport leaders and the sport community, including fellow athletes and participants, parents, coaches, and volunteers, how is safe sport in parasport even possible?

Video 20.1 Lay My Burden Down

Brock University’s Dr. Maureen Connolly says it is time to interrogate normalcy. “Fixing” disabled people is not the project. Internalizing ableism and the feeling of being a burden must stop.

Video produced for Mindset’s e-learning course Disability Literacy 101 – Inclusion Education for the Workplace. Courtesy of Disability Today Publishing Group. Used with permission. [Transcript]

Video: 20.2 Ableism at its Worst

Brock University’s Dr. Maureen Connolly discusses the difference between disableism and ableism from a social and socio-economic perspective, and the impact of both on persons with disabilities.

Video produced for Mindset’s e-learning course Disability Literacy 101 – Inclusion Education for the Workplace. Courtesy of Disability Today Publishing Group. Used with permission. [Transcript]

Quiz: which form of ableism is outright discrimination?

Unconscious Bias: Factors and Filters

Another formidable obstacle to safe sport in parasport is unconscious bias. It is understood that as humans we all have implicit (unconscious) biases. Our brains are hardwired to use shortcuts and to categorize information. It is a human characteristic.

Our biases are not always negative, and we make positive assumptions as well. Consciously, we might not even agree with our own unintentional biases. But when purposefully examined and exposed, bias can be challenged.

Unconscious bias is shaped by beliefs about the world and one’s perceptions of others in it. Danielle Peers links unconscious bias to axiology, that is, one’s value system, which may or may not be operating at a conscious level. Factors that influence that worldview include culture and socialization, religion, ethnicity, gender and sexual orientation, among others.[11]

These filters impact our perceptions of others, and harbour stereotypes and discrimination. Unconscious bias typically generalizes about a particular group of people in ways that are usually oversimplified, untrue and unfair.

Donald Sue and his co-authors suggest that micro-aggressions are subtle expressions of bias.[12] Microaggressions are frequent, subtle experiences and behaviours that reinforce stereotypes, biases, and forms of prejudice and oppression.

Microaggressions are actions that negatively target a marginalized group or individual. A microaggression is a form of discrimination that can be intentional or accidental.

People who engage in microaggressions may mean no harm toward the person or group being targeted. They may not even realize that they are making a micro-aggressive comment or action. Regardless, microaggressions can be very hurtful to the people who experience them.

Micro-aggressions can be verbal or non-verbal and typically present as offences and indignities toward someone. Mostly unintentional by well-meaning people, together and over time these small messages are intrusive and divisive by denying dignity.

The dismissive comment, “We all have a disability of some sort,” is an example of a microaggression that denies an individual’s disability experience, while the inevitable: “What happened to you?” is a denial of privacy.

Bias, stereotypes, and assumptions can be challenged through questions and self-reflection, beginning with sport leaders asking themselves if and how their actions and words reflect the values of inclusion. Leaders must move away from their comfort zones to learn about the experiences and perspectives of marginalized groups, such as the disability community. Meaningful action must follow to correct inequities, including sharing insights related to what has been learned.

When such analysis, discovery and initiation does not occur, and stereotypes and assumptions about people with disabilities are left uncontested, then we must ask the question:

How can the introduction of safe sport in parasport be authentic, and how can its immersion be truly attainable?

Disability Language: It is Not Just Semantics

Language that describes disability reflects and shapes attitudes, beliefs and biases. It can perpetuate prejudice and discrimination. Great strides have been made in disability language thanks to significant leaps forward in disability culture, but inclusive language can seem cumbersome, even for people with disabilities.

It continues to shift and most importantly, it is very personal with respect to how someone refers to their own disability. Respecting that, and using respectful language, is crucial for a safe, inclusive culture.

Justin Haegele and Cathy McKay, Danielle Peers, and Colin Cameron, among other disability studies scholars, propose that disability language and discourse can be categorized in four ways:[13]

Person-first language emphasizes the individual, whereby the individual is not defined by their disability – a“person with a disability,” not a “disabled person.” This is the preferred and safest form of disability language. Critics of person-first language, however, say that it is too formal and awkward. Person-first language began with good intentions, and the 1980s was an important time in the movement for disability rights and respect.

Identity-first language describes a person as “disabled” respectfully, as that person embraces disability as part of their identity. Instead of “person with a disability,” it is “disabled person” or amputee or wheelchair user. Today there is a pride and identity in living with a disability.

Euphemisms that are constructed to describe disability are widely considered to be politically correct language gone wrong. Substitutes like “special needs” and “differently-abled” and “handicapable” can be condescending.

Negative terminology such as cripple, invalid, handicap and retarded is inappropriate. Derogatory words deny dignity and respect.

Just as the elimination of micro-aggressions is a necessity for a safe sport environment, so is the removal of discriminatory language. Are sports leaders and volunteers referring to non-disabled people as “normal”? Normal makes people with disabilities sound abnormal by comparison.

Are sports leaders and volunteers using victim language that includes “suffers from” or “stricken with”, suggesting misfortune and evoking pity? What about “confined to a wheelchair” or “wheelchair-bound”? Neither are good. A wheelchair does not restrict; it enables mobility.

Are sports leaders and volunteers without a disability willing to invest in learning how to navigate disability language by coming to understand what is appropriate and appreciated? Respectful language is essential for an inclusive and welcoming sports space.

Governance Challenges for Safe Sport in the Parasport Sector

Challenges for safe sport in the parasport sector begin with a lack of collaboration or unification between national sport organizations, and similarly, provincial sport organizations, with respect to the unique contexts of athletes with a disability. Universal templates are not adequate.

Collaboration on further policy development and practices must include the involvement of parasport athletes, and an equitable representation of the diversity within this athlete community.

To begin definitionally, at the national level, the CPC posts the following on its website as its safe sport overview:

CPC believes that everyone involved in sport has the right to participate in a safe and inclusive environment that is free of all forms of maltreatment.

The CPC is a proud member of Abuse-Free Sport, the independent program to prevent and address maltreatment in sport in Canada. As part of our commitment, the CPC has adopted the Universal Code of Conduct to Prevent and Address Maltreatment in Sport (UCCMS).

The CPC and its stakeholders now have access to the services of the Office of the Sport Integrity Commissioner (OSIC), which is responsible for the administration of the UCCMS and serves as the central hub of Abuse-Free Sport.

We expect that any individual involved in CPC activities and all those involved in the Paralympic Movement in Canada to conduct themselves with integrity and to the highest standards of conduct, in accordance with the CPC values, as well as the UCCMS. Pursuant to the UCCMS, participants must report any actual or suspected cases of maltreatment to the Canadian Centre for Ethics in Sport (CCES) by following the process laid out below and on CCES’s website.[14]

Additionally, the Office of the Sport Integrity Commissioner (OSIC) stipulated the following parameters as part of the Abuse-Free Sport program complaints and reports process:

The Office of the Sport Integrity Commissioner (OSIC) is responsible for administering the UCCMS using trauma-informed processes that are compassionate, efficient and provide fairness, respect, and equity to all parties involved.[15]

Alternatively, individuals can report any non-UCCMS related complaints to the CPC’s independent third party, who will guide you through the complaints process and/or explore other options.[16]

In summary, the above statements demonstrate that the CPC defaults to universal policies that apply to parasport athletes, but do not address the diversity of disability and unique circumstances of the parasport athlete.[17]

At the provincial level, Swim Ontario provides a robust sport safety page on its website stating that it “believes that everyone in swimming, regardless of how they identify, has the right to feel safe and enjoy our sport at whatever level or position they participate.”[18]

With respect to equity, diversity and inclusion, Swim Ontario states:

Swim Ontario is an inclusive organization and welcomes full participation of all individuals in our programs and activities, regardless of race, ancestry, place of origin, colour, ethnic origin, citizenship, creed, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, gender expression, age, marital status, family status or disability.

Swim Ontario encourages participation in the sport of swimming and will ensure that equity, diversity and inclusion are key considerations when developing, updating or delivering Swim Ontario policies and programs.[19]

An example of a safe sport statement from a regional or local club or program is Cruisers Sports in Mississauga, Ontario. This statement, albeit more minimalistic, is much more actionable:

Cruisers Sports is committed to a safe, healthy, and harassment-free environment in every aspect of programming that our club provides. Whether the unwanted conduct is from a fellow athlete, a coach, a Board member, or an outside party, Cruisers Sports takes the incident very seriously, and endeavours to provide you with options to assist you in bringing the issue to our attention.

Whether you report an issue to a coach or any Board member, you will not have any repercussions as a result, and the report will remain confidential, and will be investigated as quickly as practicable, while protecting your identity as much as possible.[20]

Generally, when it comes to communicating safe sport policies and statement in the parasport sector, or for members with disabilities, most organizations are subscribing to the obligation to do so. The template text presents well, but how does it translate in practice? How accessible or barrier-free is it? How relevant is it, particularly to the atypical and complex disabled athlete constituency with its diverse constitution and lingering prejudicial worldviews toward it?

In an interview with one of the authors, Catharine Gosselin-Despres, Chief Sport Officer for the CPC acknowledges these challenges:

It’s a much different journey for Olympic athletes than it is for Paralympic athletes … Vulnerability is different for different disability types which is accompanied by lack of education about disability … The narrative is a push for equality. But unique disability issues are taken for granted. Equity is not equality.[21]

As for policies and procedures, Gosselin-Despres suggests that the recommendations within are not realistic. Speaking from the lens of a national sport organization she notes:

NSO [National Sport Organization] buy-in needed; it’s needed to execute the work to get it done. There needs to be consultation and education, but the money and capacity are not there to implement the strategies. Ideally, a full-time person is needed for Safe Sport in Parasport.

Right now, there is no organizational leadership representing Safe Sport in Parasport. It’s convoluted even for athletes – when to report and how to report. Board and staff training is needed. Governance issues are mixed, and in some cases, Conduct Policy is confusing. Right now, safe sport in parasport is reactionary, a moving target.

There is intense pressure to implement, but it’s a grey zone with a lot of interpretation.[22]

Peers et al., also suggest that diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) initiatives can fall prey to tokenism and enlightened ableism.[23] If we want safe sport within parasport, we must, at some level, embrace Patty Berne’s bold suggestions regarding the principles of disability justice, one of which is leadership by the most impacted, and another of which is ‘nothing about us without us’.[24]

This means that a central “Safe Sport in Parasport” agency or other appropriate structure is needed under which provincial government policies and procedures for safe sport in parasport are unified for standardization and funding.

Safe Sport in Disability Sports: Challenges and Strategies

Disability is complicated, which makes it difficult to clarify safe sport principles for disability communities. The realm of disability sports, often referred to as parasports, presents unique challenges and considerations regarding safe sport.

Ensuring safe sport in disability sports requires considering the multifaceted nature of safety concerns, the existing frameworks and regulations, and the complications in implementing universal strategies to enhance safety for all athletes with disabilities. The assignment for meaningful inclusion necessitates addressing these issues comprehensively.

A welcoming and safe environment is not as much hinged on equality – same approach as for able-bodied athletes – as it is on equity for athletes with disabilities. Prevailing societal worldviews toward disability need consideration, particularly those that are influenced by ableist attitudes and actions and implicit or unconscious biases.

Disability sports, or parasports, have gained increasing recognition and popularity in recent years, highlighting the capabilities of athletes with disabilities.[25] However, amidst the celebration of athleticism and diversity, ensuring the safety of athletes remains a paramount concern.

Unlike traditional sports and typical athlete bodies, parasports and complex athlete bodies present unique challenges related to the multiplicity of disabilities, equipment adaptations, and accessibility issues. Those complexities extend to safe sport in disability sports, particularly in consideration of existing sport frameworks and conventional systems, fundamental stereotypes and assumptions, and preponderant belief systems or worldviews with respect to disability.

The pursuit of excellence, team camaraderie, and personal growth in sports is a fundamental human endeavour, irrespective of ability. However, McCarthy et al. suggest that for disabled athletes, the journey toward sporting achievement is often accompanied by distinct challenges.[26] These challenges include:

- Accessibility;

- Intersectionality of disability and sporting participation;

- The power of inherent belief systems in sports environments, and;

- Fledgling regulatory mechanisms aimed at safeguarding athlete welfare.

Case Study:

Case Study:

Niagara Sledge Hockey League

Being physically active is not always easy for people with disabilities. “Where do I go where I’ll be included?” and “I don’t have the equipment to play,” are two consistent barriers.

Thanks to support from the Ontario Trillium Foundation and Canadian Tire Jumpstart Charities, ParaSport® Ontario (PO) has addressed the equipment challenge in the Niagara region with an infusion of adaptive sports equipment, including hockey sleds. With the support of Niagara municipalities Grimsby, Niagara Falls, St. Catharines and Welland, PO also has the “where can I play” solution: a first-of-its-kind community sledge hockey league.

Being part of a team is something that most youth and young adults with disabilities never experience. The thrill of wearing a team jersey is a first for many. Representing their community and the camaraderie of teammates is a new lived-experience for most players, adding new friendships to the fun and fitness. Community and connectivity sum up the mission of the Niagara Sledge Hockey League. Niagara’s community of individuals with a disability will find community with teammates with and without disabilities.

This program positions Niagara as a model community of inclusive parasport participation, providing the “Niagara Blueprint” for other regions province-wide.

Counterpoint:

Counterpoint:

Equity vs Equity

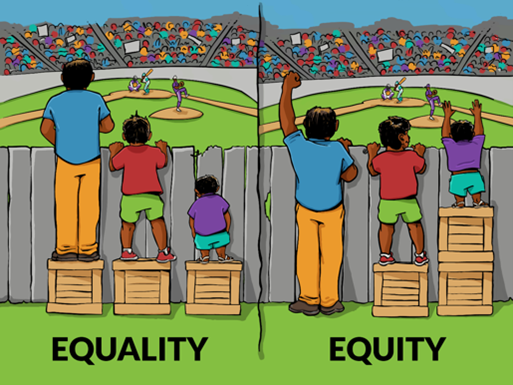

Effective allyship supports the interests of this marginalized group by amplifying the voices of disabled individuals and encouraging inclusion of their perspectives in conversations and discussions. As an ally, it is important to understand the difference between equality and equity.

Equity equates to inclusive actions and attitudes. While equality endeavours to treat everyone the same, equity considers unique experiences and situations.[27] Equity is about eliminating barriers and is the better way forward for inclusion.

Apply the concepts of equality and equity to a Safe Sport scenario where the inclusion of an athlete with a disability in a community or club program is the desired objective.

-

-

What are the potential outcomes using both equality and equity?

-

How do the outcomes differ depending on which concept is used?

-

Which outcome better supports the inclusion of an athlete with a disability into the community or club program?

-

Parasport Athlete Perspectives Explored

A 2019 research project led by Gretchen Kerr and her co-authors was designed to share the voices and visions of the Canadian parasport community regarding harms in Canadian sport, including psychological, physical, sexual and neglect-related abuse.[28] The findings identified that there are three primary pillars that contribute to a safe, inclusive, and welcoming and supportive environment:

- Values of the Sport System;

- Education, and;

- Representation

In relation to values of the sport system, disabled athletes are also under higher threat of experiencing harm in sport.[29] Gurgis et al. report that disabled athletes do not feel safe sport includes them and their experiences.[30] This research suggests that a desire to explore the shifts in culture, context, and values would be needed to actualize a safe, inclusive, welcoming, accessible sport environment for athletes and participants with disabilities.

Kerr et al. noted that a values-based culture prioritizes enjoyment, inclusion, community and feelings of belonging, promoting collaboration for everyone as valued and respected. It promotes equity and addresses current inequities and injustices experienced by marginalized athletes.[31] It must also demonstrate accountability within the sport system.

Kerr et al. also suggest that the education pillar must include building awareness of disability and intersectional identities. Here, one must encourage the sport system to challenge assumptions and biases and include best inclusion pathways and practices for sport environments.[32] Athletes in the study echoed Haegele and McKay’s concerns regarding the prevailing ignorance about the differences between integration and inclusion (i.e., belonging), and expressed agreement with Goodley’s propositions about how disabled people are all too often treated as less than human.[33]

Finally, with respect to the third pillar – representation – Kerr and colleagues contend that former athletes and disabled individuals assuming leadership positions is lacking but necessary to facilitate greater understanding of athlete needs and lived experience. Recommendations from athletes with disabilities need to inform, and be incorporated in, the design of the system and within all decision-making bodies. Stronger positions of power, influence and decision-making for athletes with disabilities would support the vision of safe sport in parasport.[34]

Kerr and colleagues concluded that safe and inclusive sport systems acknowledge, recognize, and value members beyond athletic performance safety and inclusion happen when everyone’s needs are met, goals are equitably supported, and power is given to the athletes’ voices for feedback to inform the design, development and implementation of safe, supportive sport systems.[35]

Pillars of Inclusion and Safe Sport in Parasport: Value System

Athletes with disabilities may be particularly vulnerable to exploitation and abuse, highlighting the need for robust safeguarding measures and ethical guidelines within disability sports organizations. Respecting the dignity and rights of disabled athletes entails upholding their autonomy, privacy, and bodily integrity, while also challenging ableism and discrimination within sports environments.

Maltreatment is defined as “the abuse or neglect of another person, which may involve emotional, sexual, or physical action or inaction, the severity or chronicity of which can result in significant harm or injury. Maltreatment also includes such actions as exploitation and denial of basic needs.”[36] Disabled people in general and para-athletes in particular experience maltreatment in ongoing ways.[37]

The 2019 prevalence study by Kerr et al. reported a high rate of psychological harm among able-bodied and para-athletes, followed by neglect, sexual harm and physical harm. Vulnerable groups, such as children with disabilities, face heightened risk—a 1.5 to 3 times greater harm likelihood.[38]

The comparative statistics presented in the study underscore the disparities between disabled and non-disabled elite athletes in terms of support, funding, and counseling, and echo the concerns of Tan et al. and Pearson and Misener regarding the intersected and complex character of disability discrimination in society in general and in sport in particular.[foonote]Tan et al., 2019; Pearson and Misener, 2025[/footnote] Further, according to Pearson and Misener, intersected identities are particularly vulnerable to doubled or compounded discrimination.[39]

Kerr et al.’s study was limited by its small sample size of para-athletes and its data should be interpreted with caution. The findings shine a light on experiences of maltreatment, but a larger study is required before drawing definitive conclusions.[40]

Pillars of Inclusion and Safe Sport in Parasport: Personal & Professional Education

Disabilities manifest in diverse forms, each presenting unique safe sport considerations. Para-athletes have a range of varying disabilities, some strictly physical, some cognitive, while some athletes present with both. What safe sport means to those individual athletes will differ because they experience safety differently in response to their unique challenges which presents unique challenges in the sporting arena.

From physical impairments to intellectual disabilities, understanding the diverse nature of disabilities is essential for implementing effective safety measures. Intersectional identities shaped by race, gender, socioeconomic factors, and sexual orientation, also influence experiences and vulnerabilities of athletes with disabilities within sport. Empowering disabled athletes through education, advocacy and support networks, can enhance athletes’ abilities to assert personal rights and boundaries in sports.

In Gurgis et al.’s 2022 study, participants offered recommendations related to advocacy, education and community engagement to advance a culture of safe sport characterized by principles of equity and inclusion, rather than abuse prevention. Participants expressed the importance of education to increase people’s awareness about the lived experiences of equity-deserving groups.[41] Danielle Peers and colleagues further emphasized these initiatives in their work on the prevalence of ableist assumptions and discourses in adaptive physical activity textbooks and practitioner preparation.[42]

In their 2022 study, Gurgis et al. found that the participants’ understanding of Safe Sport extended beyond the traditional focus on preventing physical, sexual or psychological abuse. Unlike the perspectives put forth by many sport organizations, the participants also emphasized the importance of developing fair, inclusive, accessible and non-discriminatory sport cultures.[43]

According to the participants, however, safe sport is an improbable, idealistic concept that is not likely to be fully realized by these athletes because they are discriminated against for how they identify. All the participants described being discriminated against through verbal and behavioural microaggressions, as well as systemic barriers imposed by the sport environment, thus influencing the perception of their sport experiences as being unsafe. Participants claimed that safe sport was relevant and attainable for athletes who appear to fit within societal-normative identities more so than for athletes from equity-deserving groups.[44]

Pillars of Inclusion and Safe Sport in Parasport: Equitable Representation

Disabled athletes should have the autonomy and agency to make informed decisions about their participation in sports, including choices related to Safe Sport. Gurgis et al. report a growing concern that the voices of athletes, and in particular, athletes from equity-deserving groups, are unaccounted for in the development and advancement of safe sport initiatives. The findings of their study revealed that equity-deserving athletes perceived Safe Sport as an unrealistic and unattainable ideal that cannot fully be experienced by those from equity-deserving groups.[45]

Thomas Couser proposes that any representation of disabled people must necessarily include insiders’ accounts, must allow access to the complexities of disabled life (that is, disabled people choose what to reveal, and in doing so, allow non-disabled people controlled access to aspect of disabled life that they likely are profoundly unaware of), must include authentic consultation and first person reporting when possible, must avoid the trappings of the expectations to make non-disabled readers or listeners ‘comfortable’, and must include a correction to the stereotypical representations of disabled life.[46] This kind of representation by its very presence has the potential to be a cultural critique as well as an authentic account.

Gurgis et al.’s research reiterates the disability community’s contemporary refrain: “Nothing for or about us without us.” The lived experience perspective is critical to shaping appropriate and applicable Safe Sport parasport policies and practices for athletes with a disability.[47]

In Practice:

Inclusive Training Solutions

A fellow student in your program is a Paralympic hopeful in athletics, a 200m and 400m sprinter. An above-the-knee amputee, the para-athlete is seeking high-performance coaching and training opportunities to prepare for the national championships and to qualify for international competition.

She receives training information from her provincial sport organization (PSO) but needs help executing the weekly program with hands-on coaching expertise. Training in isolation has been difficult, and the athlete knows that she would benefit from training partners and the comradery of a team environment. She also knows that her disability prevents her from competing on the varsity track team, but wonders if there is still an opportunity to train with the school team.

- How can you be an ally for this athlete?

- Could the Kinesiology department be enlisted to determine her efficiency loss to develop equitable training regimes with non-disabled athletes?

- How should she approach the Human Kinetics’ athlete director and team coach?

- How might they include her and support her paralympic dream?

Conclusion

Safe sport policy and education must include the prevention of social injustices, and the promotion of inclusive, rights-based sport that accommodates the unique needs of diverse, equity-deserving participants.[48] For example, sport organizations may consider mandating all sport stakeholders to complete anti-discriminatory education.

Additionally, sport organizations and different levels of government responsible for the governance of sport must integrate and enforce equity and inclusion policies. These policies should address consequences for discriminatory behaviours, requirements for equal employment opportunities, and standards regarding the accessibility of resources and support spaces.[49]

Implementing education and policies related to social injustice issues within the safe sport discourse demonstrates a rejection of the “one-size-fits-all” mentality that assumes everyone understands and experiences safe sport similarly. Further, sport organizations must commit to removing barriers that interfere with the recruitment of equity-deserving leaders. Prioritizing diverse leadership across safe sport may further shape how safe sport is conceptualized and advanced.

The advancement of safe sport for underrepresented groups is contingent on having diverse leaders who can empathize with equity-deserving athletes. It is essential that sport organizations enhance accountability measures to confront the complacent nature of safe sport for equity-deserving athletes, which to this point, has failed to consider the subtle, yet harmful ways in which sport and its participating stakeholders affect equity-deserving athletes.[50]

Kerr et al.’s 2019 study determined that there is a need for an independent body. They included an athlete’s statement that emphasized the need for an anonymous reporting method. They advocated for a separate, unbiased organization or individual where athletes can talk about concerns and complaints without worrying about repercussions to their athletic career.[51]

Without discovery, empathy and respect of differences that pave the pathways to allyship, safe sport as it is envisioned for the collective sport sector is not realistic for its parasport contingent. Allyship is attainable through disability inclusion education that challenges ableist belief systems and language, including explicit and implicit bias, and affords authentic opportunities for learning and unlearning.

The disability diversity, equity and inclusion space is an ongoing journey of learning new perspectives and unlearning stereotypes and assumptions. Different factions of the sport sector are at different points in that journey. Incorporating and appreciating the lived experiences of people with disabilities of all types for an authentic collaborative approach to safe sport can provide an essential foundation for the aspirations of safe sport in parasport.

Self-Reflection

The disability diversity, equity and inclusion space is an ongoing journey of learning new perspectives and unlearning stereotypes and assumptions. Like the elementary and secondary school systems, and workplace environments, different factions of the sport sector are at different points in that journey.

- You recall a fellow student in high school being excluded from gym class and intramural sports because of his physical disability. From what you have learned in this chapter, what steps could have been taken to have created a safe space of inclusion for that student? (Note: his disability can be determined as you wish; timekeeping and scorekeeping are not inclusive options.)

- Reflect on something that you might have said or thought about a person with a disability who you met in school, workplace or in your community that may be classified as ableist thinking or received by that individual as a micro-aggression. How could you have approached the situation differently to avoid reinforcing ableist attitudes? What steps can you take to unlearn biases or assumptions about people with disabilities?

Further Research

Sourcing para-athlete anecdotal data and lived experiences with safe sport, and garnering recommendations from these athletes for more informed and inclusive policies and practices for safe sport in parasport.

Exploring the relational tensions that might exist between disability identified active leisure and para-sport participants and their non-disabled allies, advocates, support personnel, and volunteers.

Key Terms

Suggested Assignments

- Comparative Policy Analysis:

-

Look up and review a safe sport policy from a parasport organization, and one from a mainstream sport organization.

- Create a brief summary for each policy, including key take aways, strengths and weaknesses.

- Highlight differences in how each policy addresses equity, inclusion, and specific needs of athletes.

- Provide your own assessment on what mainstream sports can learn from parasport policies.

2. Media Critique:

-

Locate and review media coverage of a parasport event or athlete.

- Analyze the extent to which the media coverage promotes safe sport principles or perpetuates biases.

- Suggest ways media representation could be improved to align with the chapter’s vision of safe sport in parasport.

Figure Descriptions

Figure 20.1 This figure demonstrates the Medical Model of Disability. The main image is a blue background with white text which reads “Medical Model of Disability Now outdated, this model views disability as something that’s “wrong” with the person. It says the “impairment” is a problem to be fixed. Key Criticism Fixing is not the project. Disability is part of our human condition.” To the right is an image of a hand on a wheel of a wheelchair, the image is tinted blue. [return to text]

Figure 20.2 This figure demonstrates the Social Model of Disability. The main image is a blue background with white text which reads “Social Model of Disability More modern, this model views disability as something that exists because of physical and attitudinal barriers in society. Key Criticism A fully barrier-free society for all is not possible. No amount of social change negates the disability.” To the right is an image of a man in an electric wheelchair facing up a flight of stairs; dark hair, blue jacket, the image is tinted blue. [return to text]

Figure 20.3 This figure demonstrates the Human Rights Model of Disability. The main image is a blue background with white text which reads “Human Rights Model of Disability Becoming more standard, this view looks to society’s understanding of barriers based on the values of dignity and inclusion. Key Criticism The onus is on society to ensure accessibility, inclusion and belonging for all.” To the right is an image of a leg standing on a yellow line; wearing blue jeans and sneakers, the image is tinted blue. [return to text]

Image Descriptions

Key Dates Background Image This image is of two low vision runners with guides; all males, blurry neon lights in the background, guides in orange t-shirts, one runner in black tank top, one in red tank top; two runners wearing dark glasses; one guide, Caucasian, wearing dark glasses; other guide is African American, no glasses. [return to text]

Image 1 This image is of a quad amputee woman in white sailboat, working with the sail, leaning to the right; red life jacket, blue baseball cap, long hair blowing in the wind; water in the background. [return to text]

Image 2 This image is of a young woman, single leg amputee with spring lower leg poised on starting block on a track; she has long hair, in a ponytail and wears read tank top and floral biker shorts; crash mats and other training equipment in the background. [return to text]

Image 3 This image is of a goal ball female athlete in a side lying defensive position preparing to stop the large blue goal ball coming towards her; blond hair, white headband, black tights and long sleeved t shirt, red tank top over the black t shirt, white socks, black athletic shoes; grey gymnasium floor, while lines on the floor, mats in the background. [return to text]

Image 4 This image is of six wheelchair curling athletes, all using wheelchairs; one other person in the upright position; all on a curling rink surface, white with a blue circle inside a larger red circle; two women and one man in the foreground; the most foregrounded woman is pushing the curling rock with the arm extender. [return to text]

Image 5 This image is of two male wheelchair users, side by side; the smaller male, dark hair, in a green t-shirt, holds a small white ball, preparing to throw; the larger male in a yellow t shirt and a blue baseball cap is next to the smaller male preparing to throw; blurry gymnasium wall in the background. [return to text]

Image 6 This image is of four wheelchair basketball athletes in BB chairs, wheeling to the sidelines; one woman, perhaps the coach, awaits the two athletes in the red tank top; the other two athletes have blurred spectators in their background; the referee wears grey; the gymnasium floor is bright green. [return to text]

Image 7 This image is of a male upper arm amputee holds a red ball between his stump and his cheek; he has short brown hair, glasses, and some beard stubble on his face; he wears a black t shirt with the word CANADA in white letters. [return to text]

Image 8 This image is of an athlete in a rowing shell; the athlete holds two oars and is in the process of pulling on the oars; the boat is on the water with greenery in the background; the athlete wears dark glasses, a white baseball hat and a red and white rowing singlet; the athlete’s arms are outstretched, and knees are bent. [return to text]

Image 9 This image is of a wheelchair basketball male athlete sitting high in the wheelchair, with a basketball poised to shoot; the athlete’s hair is short and dark; he wears a red tank top and black pants; the background is a blurry spectator audience. [return to text]

Image 10 This image is of an adult female swim instructor with white swim hat with a red maple leaf on it is smiling and interacting with two children in a swimming pool; the girl wears a blue swim suit, goggles, and a yellow swim hat with the word ‘flames’ in black letters; the boy wears black trunks and blue and green goggles; all three people are close together in the water; there is a blurry wall back ground and one side of a swim ladder near the adult female. [return to text]

Image 11 This image is of three people in sit skis on snow; all three wear winter clothing and hats and have pinnies with numbers on them; all three are using ski poles; the person in the foreground has one pole lifted; the person in the middle has one pole lifted; the third person has both poles in the snow. [return to text]

Image 12 This image is of a female wheelchair athlete throwing a discus; her arm is outstretched as she releases the discus; she wears a red t-shirt, has neck length brown hair and is wearing a head band; she uses one arm to brace herself against her chair; she has bare feet; there is black discuss netting and blurry greenery is in the background. [return to text]

Image 13 This image is of three para-ice hockey athletes are on the ice in sledges; each wears blue hockey jerseys and hold sledge sticks; the two larger athletes wear black helmets and the smaller athlete wears a red helmet; there is a partial image of a person in an upright position to the side; the ice is white and there is a background of white hockey boards with a red and black stripe. [return to text]

Image 14 this image is of an equality and equity comparison in visual form with three cartoon images trying to observe a baseball game over a fence; coloured spectators are opposite the fence; for equality, the three boxes of the same height are in front of the fence; three people of different heights stand on the boxes trying to see over the fence; the tallest person gets good clearance and can see over the fence to observe the baseball game on the field on the other side of the fence; the middle sized person can get head and some shoulders over the fence and can see the game; the shortest person cannot see over the fence. Next image, for equity, shows the boxes distributed to the shortest person gets two boxes, the middle-sized person gets one box, and the tallest person does not get a box because he does not need one. Now everyone can see over the fence. [return to text]

Image 15 This image is of a para-swimmer in a swimming lane in the water near the side of the pool with a coach-observer on deck beside the swimming lane using a tapping wand; there are several people wearing yellow in the background; the pool has glass windows as walls, the lane markers are blue and white, there is a red lifesaver ring hanging off a lifeguard chair, the tapper wears black clothes and red crocs, the water appears to be blue. [return to text]

Image 16 This image is of a male wheelchair athlete; chair has court wheels with red inserts; athlete has short light brown hair, wears black with a pinnie with number 23 in white; he is looking to the side, carrying a round, white ball on his lap; he wears grey fingerless gloves; blurry audience in the background. [return to text]

Image 17 This image is of a female para-athlete in equestrian riding uniform of black hat, blue blazer, beige pants, and boots; she is smiling and standing between her dark blue chair and a chestnut-coloured horse with a white nose; field and trees in the background. [return to text]

Image 18 This image is of a sitting volleyball game in a gymnasium with spectators viewing while standing in front of the far wall; there are three athletes in green on the right side of the image looking over the net; there is a blue and yellow ball suspended over the net; the two athletes wearing red on the opposite side of the net are blocking the ball; an official wearing black and using a whistle stands at the blue post near the far wall. [return to text]

Image 19 This image is of a young female single leg amputee para-athlete using a single spring prosthetic runs on a track; she has a long ponytail that flows behind her head and wears pink shorts and a blue tank top; blurry outdoors with trees in the background. [return to text]

Image 20 This image is of a young male para-ice hockey athlete sits in the dressing room against the wall, on a bench, next to his sled; his gloves are on the bench and his sticks are crossed over in front of his sled; his brown hair looks damp; he wears a red hockey jersey with the team name in white letters and a large A on the upper shoulder of the jersey; there is a white hockey jersey hanging on the wall behind him. [return to text]

Further Reading

Mindset. (n.d.). Disability Inclusion Education. https://disabilitytodaynetwork.com/mindset-d-e-i-course.

ParaSport Ontario. (n.d.). Physical Literacy. https://parasportontario.ca/resource-centre/physical-literacy.

Women’s Parahockey of Canada. (n.d.). Safe Sport. https://www.wphcanada.com/safe-sport.

Sources

Abuse Free Sport. (n.d.). Important Program Update. Abuse Free Sport, Office of the Sport Integrity Commissioner. https://sportintegritycommissioner.ca.

American Psychological Association. (2018, April 19). Maltreatment. In APA Dictionary of Psychology. https://dictionary.apa.org/maltreatment.

Bhargava, I. (2023, May 16). Western University researchers want to learn more about safe sport policies for para athletes. CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/london/western-university-researchers-want-to-learn-more-about-safe-sport-policies-for-para-athletes-1.6844480.

Berne, P. (2015, June 10). Disability justice—A working draft by Patty Berne. Sins Invalid. https://www.sinsinvalid.org/blog/disability-justice-a-working-draft-by-patty-berne.

Cameron, C. (Ed.) (2014). Disability Studies-a student’s guide. Sage.

Canadian Paralympic Committee. (n.d.-a.). About the CPC. Canadian Paralympic Committee. https://paralympic.ca/about/overview/.

Canadian Paralympic Committee. (n.d.-b.). Safe Sport. Canadian Paralympic Committee. https://paralympic.ca/about/governance/safe-sport/.

Connolly, M. (2023). Ableism, hiding in plain sight: An introduction in four acts. In D. Goodwin and M. Connolly (Eds.), Reflexivity and change in adaptive physical activity (pp. 1-7). Routledge.

Couser, G. T. (2013). Disability, life writing and representation. In Lennard Davis (Ed.), The Disability Studies Reader, 4th ed. (pp. 531-534). Routledge.

Cruisers Sports. (n.d.). Safe Sport. Cruisers Sports. https://cruisers-sports.com/sports/safesport.shtml.

Goodley, D. (2021). Disability and Other Human Questions. Emerald Publishing.

Gurgis, J. J., & Kerr, G. A. (2021). Sport administrators’ perspectives on advancing safe sport. Frontiers in sports and active living, 3, 630071.

Gurgis, J.J., Kerr, G., and Darnell, S. (2022). Safe Sport Is Not for Everyone”: Equity-Deserving Athletes’ Perspectives of, Experiences and Recommendations for Safe Sport. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 832560. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.832560.

Haegele, J. A. & McKay, C. (2025). Theoretical and social considerations of adaptive sport and recreation. In Robin Hardin & Joshua R. Pate (Eds.) Introduction to Adaptive Sport and Recreation (pp. 1-13). Human Kinetics.

Haller, B. (2010). Representing disability in an ableist world: Essays on mass media. Avocado Press.

Joseph, J. (2021). Are We One? The Ontario University Athletics Anti-Racism Report. Ontario University Athletics.

Kerr, G., Willson, E. A., and Stirling, A. (2019). Maltreatment in Canada: A Focus on Para-Athletes. Canadian Paralympic Committee. https://sirc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Report-of-Para-Athletes-Experiences-of-Maltreatment_Oct21_2019.pdf.

Kerr, G. (2021). Canadian Parasport Members’ Views on Safe, Inclusive, & Accessible Sport [Public Lecture], University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Kerr, G., Battaglia, A. (2024). The Crisis of Toxic Cultures in Competitive Sport. In: Strauss, B., Buenemann, S., Behlau, C., Tietjens, M., Tamminen, K. (Eds.), Psychology of Crises in Sport (pp. 199-213). Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-69328-1_14.

McCarthy, K., Bixby, L., Kennedy, W. (2025). Barriers and opportunities for access and inclusion. In Robin Hardin & Joshua R. Pate (Eds.), Introduction to Adaptive Sport and Recreation (pp. 15-31). Human Kinetics.

Murphy, C. (2024, April 13). What’s the Difference Between Equity and Equality? Health. https://www.health.com/mind-body/health-diversity-inclusion/equity-vs-equality.

Pearson, E. & Misener, L. (2025). Media and disability sport. In Robin Hardin & Joshua R. Pate (Eds.), Introduction to Adaptive Sport and Recreation (pp. 89-102). Human Kinetics.

Peers, D. (2018). Engaging axiology: enabling meaningful transdisciplinary collaboration in adaptive physical activity. Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly (APAQ). 35, 267-284. https://doi.org/10.1123/apaq.2017-0095.

Peers, D., Joseph, J., Chen, C., McGuire-Adams, T., Fawaz, N. V., Tink, L., et al. (2023). An intersectional Foucauldian analysis of Canadian national sport organisations’ ‘equity, diversity, and inclusion’(EDI) policies and the reinscribing of injustice. International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics, 15(2), 193–209. https://doi.org/10.1080/19406940.2023.2183975.

Pearson, E. & Miserner, L. (2021, September 1). Paralympians still don’t get the kind of media attention they deserve as elite athletes. The Conversation, Retrieved April 5, 2025 from https://theconversation.com/paralympians-still-dont-get-the-kind-of-media-attention-they-deserve-as-elite-athletes-166879.

Peers, D., Eales, L.,& Goodwin, D. (2023). Disableism, ableism, and enlightened ableism in contemporary adapted physical activity textbooks: practicing what we preach? In D. Goodwin and M. Connolly (Eds,) Reflexivity and Change in Adaptive Physical Activity (pp. 34-46). Routledge.

Sue, D. W., Capodilupo, C. M., Torino, G. C., Bucceri, J. M., Holder, A. M. B., Nadal, K. L., et al. (2007). Racial microaggressions in everyday life: implications for clinical practice. Am. Psychol. 62, 271–286. 10.1037/0003-066X.62.4.271.

Sue, D. W., Alsaidi, S., Awad, M. N., Glaeser, E., Calle, C. Z., & Mendez, N. (2019). Disarming racial microaggressions: Microintervention strategies for targets, White allies, and bystanders. American Psychologist, 74(1), 128–142. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000296.

Swim Ontario. (n.d.). Sport Safety. https://www.swimontario.com/sport-safety/.

Tan, B. S., Wilson, E., Campain, R., Murfitt, K., & Hagiliassis, N. (2019). Understanding negative attitudes toward disability to foster social inclusion: An Australian case study. Inclusion, equity and access for individuals with disabilities: Insights from educators across world, 41-65.

Vertommen T., Schipper-van Veldhocken N., Wouters K., Kampen J. K., Brackenridge C., Rhind D. J. A., Neels K., & Van Den Eede F. (2016). Interpersonal violence against children in sport in the Netherlands and Belgium. Child Abuse & Neglect, 51, 223-236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.10.006.

Willson, E., Kerr, G., Stirling, A., and Buono, S. (2021). Prevalence of maltreatment among Canadian National Team athletes. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 1–23. 10.1177/08862605211045096.

Willson, E., Kerr, G., Battaglia, A., & Stirling, A. (2022). Listening to athletes’ voices: National team athletes’ perspectives on advancing Safe Sport in Canada. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living, 4, 840221. https://doi.org/10.3389/fspor.2022.840221.

- Bhargava, 2023 ↵

- Cameron, 2014; Peers, 2018; Goodley, 2021 ↵

- Cameron, 2014 ↵

- Cameron, 2014; Connolly, 2023; Goodley, 2021; Peers, 2018 ↵

- Goodley, 2021; Peers, 2018 ↵

- Hall, 2010 ↵

- CPC, n.d.-a ↵

- Connolly, 2023; Peers, 2018; Peers et al., 2023 ↵

- McCarthy et al., 2025 ↵

- Peers, 2018; Connolly, 2023 ↵

- Peers, 2018 ↵

- Sue et al., 2007, 2019 ↵

- Haegele and McKay, 2025; Peers, 2018; Cameron, 2014 ↵

- CPC, n.d-b ↵

- Abuse Free Sport, n.d. ↵

- CPC, n.d-b ↵

- Peers et al., 2023 ↵

- Swim Ontario, n.d. ↵

- Swim Ontario, n.d. ↵

- Cruisers Sports, n.d. ↵

- C. Gosselin-Despres, personal communication, February 21, 2024 ↵

- C. Gosselin-Despres, personal communication, February 21, 2024 ↵

- Peers et al., 2023 ↵

- Berne, 2015 ↵

- Pearson & Misener, 2021 ↵

- McCarthy et al., 2025 ↵

- Murphy, 2024 ↵

- Kerr et al., 2019 ↵

- Vertommen et at., 2016; Gurgis et al., 2022; Wilson et al., 2021; Wilson et al., 2022 ↵

- Gurgis et al., 2022 ↵

- Kerr et al., 2019 ↵

- Kerr et al., 2019 ↵

- Haegele and McKay, 2025; Goodley, 2021 ↵

- Kerr et al., 2019 ↵

- Kerr et al., 2019 ↵

- American Psychology Association, 2018 ↵

- Goodley, 2021; Kerr et al., 2019; Kerr, 2021; Kerr et al., 2024; Wilson et al., 2021 ↵

- Kerr et al., 2019 ↵

- Pearson and Mister, 2025 ↵

- Kerr et al., 2019 ↵

- Gurgis et al., 2022 ↵

- Peers et al., 2023 ↵

- Gurgis et al., 2022 ↵

- Gurgis et al., 2022 ↵

- Gurgis et al., 2022 ↵

- Couser, 2013 ↵

- Gurgis et al., 2022 ↵

- Joseph et al., 2021 ↵

- Joseph et al., 2021 ↵

- Joseph et al., 2021 ↵

- Kerr et al., 2019 ↵