Stress Injury Mitigation

Learning Objective

To define and build awareness of the causes and prevention of stress injuries in outdoor leaders.

To introduce self-assessment tools, including language, stress mitigation and resilience-building strategies.

To understand how stress management contributes to leader’s decision making and judgment capacity.

Introduction to Stress Injuries

What is a Stress Injury?

A Stress Injury is an occupational injury that occurs in the presence of overwhelming stress and exposure to psychological stress in the line of duty. This includes chronic low level exposure and unrelenting stress – not just a single stressful event (though it can be).

Key Characteristics of Stress and Stress Injuries:

- Physiological Effects: Stress injuries manifest through changes in vital signs such as increases in respiration, heart rate, blood pressure, changes in skin condition, pupils, etc. These changes can include physiological responses like sustained high blood pressure during states of hyperarousal, and can persist, leading to long term health concerns if stress becomes chronic, or hormone production does not stop as it should when stressors are removed.

- Continuum of Severity: Stress injuries exist on a continuum, ranging from lower-severity stress reactions to more severe cases like Post Traumatic Stress (PTS). The severity spectrum reflects the impact and duration of stress on an individual.

- Addressable and Mitigatable: Recognizing stress injuries early is crucial as they can be addressed and mitigated through appropriate interventions and support.

- Universal Impact: Stress injuries can affect anyone, regardless of their background, profession or level of experience.

- In the emergency responder world, stress injuries are also referred to as Critical Incident Stress (CIS).

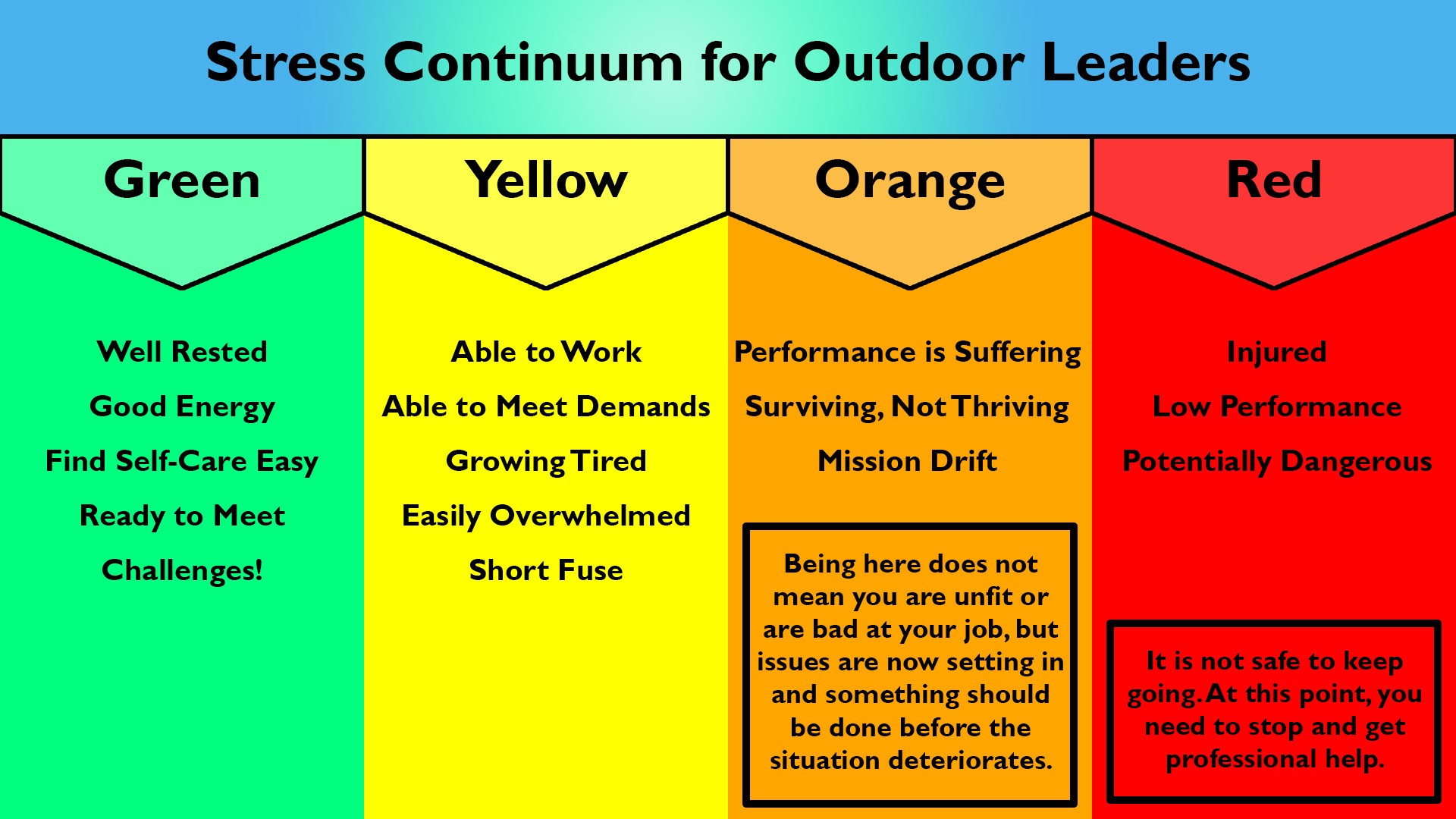

Stress Continuum

The Stress Continuum is an identification tool and a temperature check. Take a look at the Stress Continuum below and then think – where do I fit on the chart right now?

Self Check in Questions for Stress Accumulation

What do you normally like to do?

- Assess your usual activities and habits, as changes in these patterns can indicate stress accumulation.

- Establish a routine of regular self-check-ins to monitor shifts in your preferences and behaviors.

Have your habits/activities changed, and why?

- Reflect on any changes in your habits or activities and explore the reasons behind these shifts.

- Challenge yourself to discern whether these changes are justified or if they may indicate stress accumulation.

What signs have you experienced this week thus far?

- Identify specific signs or symptoms you have experienced during the week that might be indicative of stress accumulation.

- Acknowledge both physical and emotional indicators to gain a comprehensive understanding.

What are your warning signs that you should stop or pause?

- Recognize the personalized warning signs that suggest you need to take a break or pause.

- This could include physical symptoms, changes in mood, or other cues that signal the need for self-care.

How Stress Injuries Occur in the Outdoor Industry

- Traumatic Events or Prolonged Exposure:

- Stress injuries can result from a single significant traumatic event or prolonged exposure to unrelenting stress.

- Micro-accumulations of daily stresses without adequate recovery time can also contribute to stress injuries.

- Common Stressors in the Outdoor Industry:

- Prolonged exposure to micro-stressors is more common than singular traumatic events in the outdoor industry.

- Stressors include societal conditions (inequities, racism, sexism, etc.) and daily challenges like decision fatigue, group dynamics, environmental conditions, lack of support, isolation, extended periods of responsibility, and insufficient recovery time.

- Seasonal Nature of Outdoor Work:

- Outdoor work, especially guiding, tends to be seasonal, leading to a compressed schedule with many field days in a short period.

- This dynamic necessitates individual and organizational strategies to manage and reduce stressors.

- Preventing Burnout and Long-Term Injuries:

- Incorporating preventive practices is crucial to avoid minor stress injuries turning into burnout or long-term issues.

- Strategies should focus on both individual well-being and organizational support.

- Burnout and Compassion Fatigue:

- Stress injuries can manifest as Burnout and Compassion Fatigue., affecting the mental and emotional well-being of individuals in the outdoor industry.

Understanding the diverse sources of stress in the outdoor industry and implementing proactive strategies is essential for preventing and mitigating stress injuries, fostering a healthier and more sustainable work environment.

The 3 Stages of Burnout

|

1. Emotional exhaustion

|

|

2. Cynicism & Detachment

|

|

3. Reduced Performance or “Mission Drift”

|

Stress and the Body

Stress can be beneficial, signaling the body to release hormones like cortisol and adrenaline. These hormones, along with many others, prepare the body to respond to challenging events, increasing heart rate, blood pressure, sensory awareness, and promoting faster responses.

During a normal stress response, after a challenging event the brain signals the body to stop producing stress hormones. Hormone levels dissipate, and the body returns to its normal baseline.

Problems arise when stress is prolonged or extreme, preventing the brain from signaling the “all-clear” to stop stress hormone production. Elevated stress hormones become the new baseline, potentially leading to detrimental health effects.

Chronic stress can damage the immune system, and negatively impact sleep patterns. Over the long term, chronic stress increases the likelihood of developing health conditions such as diabetes, heart disease, and other health issues.

Understanding the balance between beneficial and detrimental aspects of stress is crucial. While acute stress responses are natural and adaptive, chronic stress can have serious implications for physical and mental health. Managing stress through healthy coping mechanisms and seeking support when needed is essential for overall well-being.

The Rider and The Elephant Metaphor

Imagine a rider atop an elephant, representing different parts of our brain:

- The Elephant (Limbic Brain):

- Responsible for behavioral and emotional responses, including the “fight or flight” response.

- Represents our instinctual and emotional reactions.

- The Rider (Neocortex):

- The thinking part of our brain, responsible for rational thought, reason, perception, and logic.

- Represents our ability to navigate and make informed decisions.

When the Rider is in control, it can guide the Elephant around perceived threats, like distinguishing a rock from an alligator.

Stress, especially prolonged or unrelenting stress, can fatigue the Rider. As stress accumulates, the Rider may lose control by gradually letting go of the reins.

Riding with only one or two fingers on the reins signifies working in a stressed state. A distracted or fatigued Rider may lose the ability to navigate even minor challenges.

Riding with only one or two fingers on the reins is what it looks like to be working in a state of stress; it doesn’t take much to lose our grip. When we are in a state of stress, even a small trigger can cause us to sustain a stress injury. Something that could normally be navigated around – like a rock that looks vaguely like an alligator – can no longer be handled, and the Rider loses control to the Elephant and sustains an injury.

The goal of stress injury mitigation is to interrupt that stress accumulation and fire the nervous system’s “all clear” signal in real time: noticing those fingers slipping off the reins and getting them back on so that the Rider remains in control.

Acute Stress Reaction Signals (ASR Signals)

Acute Stress Reaction Signals encompass a range of responses triggered by a stressful event. These signals vary among individuals and may include:

- Physical: Upset stomach or digestive issues, tremors, fatigue, rapid heart rate, headaches, increased blood pressure, fainting/dizziness, etc.

- Cognitive: Poor concentration, reduced attention span, short-term memory problems, nightmares, confusion, distortion of events, negative self talk, blaming attitude, etc.

- Emotional: Shifts in mood such as increased irritability, and heightened emotional sensitivity.

- Behavioural: Withdrawal, difficulty relaxing, sleep disturbances, increases in substance use (smoking, alcohol, drugs), hyper-vigilance, changes in activity level, etc.

These signs of distress are common reactions to acute stress and typically do not require immediate intervention in the short term. In most cases, they resolve on their own. However, if these signals persist or become debilitating, seeking professional help is crucial. Unaddressed Acute Stress Reaction may potentially evolve into post-traumatic stress reactions (PTSR).

Recognizing personal ASR signals is vital for effective stress management. Proactively working to interrupt stress accumulation is akin to regaining control as The Rider of The Elephant.

Discussion Questions

● What signs do you notice when you start feeling stress?

● What signs have you experienced in response to a stressful event?

● What are your warning signs that you should stop or pause what is happening?

The Goals of Stress Injury Mitigation

When a critical incident occurs, we often find that support floods in – this is a reactive approach.

The goal is to move towards a proactive approach; building awareness and stress mitigation techniques, and by dealing with the accumulation of micro stressors that create conditions within us that primes us for a trigger to push us over the edge to injury. When this happens the trigger doesn’t need to be something big – it can be almost anything, even a small event.

Tools for Stress Mitigation

Prevention: The goal and purpose of Stress Injury Mitigation is to try to prevent small things from becoming something larger. Continued and active awareness is paramount. Take note of your stress levels; your body will know and notice micro changes before your brain does and will start reacting. The Stress Continuum above is a helpful tool to build language and gage your level of stress. Below, we will provide some concrete tools for stress mitigation.

Practices within the Risk Management Framework contribute to stress reduction. Components such as Shared Mental Modelling, Closed Loop Communication, Practicing Ongoing Vigilance, Situation Awareness, and Workload Management play a role in managing both risk and stress.

The Power of Sleep

When you sleep, your brain greatly reduces the production of norepinephrine, which is a hormone involved in our “fight or flight” stress response and also promotes wakefulness or alertness. With our norepinephrine reduced, the body can relax and we are able to rest and to dream (dreams have been related to the mind’s ability to process and recover from stress and trauma).

We know that sleep deprivation affects our cognitive abilities: it also increases emotional reactivity, and a whole host of negative effects that humans are not aware of when it’s happening. Humans do not excel at realizing how dysfunctional we are when sleep deprived – we always think we are doing just fine. We also know that sleep can be hard to get when stressed, and since a lack of sleep exacerbates stress and stress injuries, we need to prioritize strategies for getting good sleep before, and during our time in the field.

The Power of Talking

Beyond the communication of information, engaging in conversation with others has many benefits. One is the release of oxytocin, a hormone associated with pleasurable feelings, comfort, and empathy. Oxytocin is itself a stress hormone released in the body during the stress response, playing a role in reducing blood pressure, and keeping cortisol levels in check. It also stimulates a variety of positive social interactions, prompting us to reach out and connect with others.

When you are comforted by others after stressful events or experiences, oxytocin is released which helps dissipate stress hormones and helps your body return to baseline. Oxytocin also contributes to increased feelings of trust and cooperation, further reducing stress and helping strengthen social connections and emotional bonds which can mitigate stress in the future.

Practice your talking skills! Creating and maintaining connections with teammates can interrupt stress injury formation. The simple act of talking to others serves as a powerful tool in managing and mitigating stress, contributing to overall mental well-being. Conversations that involve active listening, emotional support, and empathy can create a calming effect, helping to alleviate the physiological and psychological aspects of stress.

5 Tools for Support

These are tools that can support us in managing stress. These tools are preventative, empowering, and can be used anytime to proactively manage and mitigate stress!

These tools can be used to support yourself and others. Make a habit of using them before they are needed, so you build a habit and know how to use when you need them.

Calm

Help identify things that brings calmness to yourself and others. Examples include space, time, activity, location, and people. If you are helping others, being a regulated presence can create a calm atmosphere for the other person.

Safety

Identify and remove yourself or others from stressors, or remove stressors from your environment by creating or going to a safe zone. Surround yourself with people you feel safe with (support systems).

Connection

Connection, along with self-efficacy, are the most important factors that contribute to the ability to integrate stress and build resilience.

Having even one person you feel you can talk to and reach out to no matter what is a huge part of healing and building resilience. Unconditional positive regard and someone seeing you and hearing you contribute to connection and mitigates stress. Do you have someone you can reach out to?

Self-Efficacy

Self-efficacy, along with connection, are the most important factors that contribute to the ability to integrate stress and build resilience.

Self-efficacy is having a sense of control over your choices, a sense of agency. This also includes recognizing your contributions and things you have done well. Helping recognize the original reason for entering a line of work and having that sense of purpose endure is building resilience.

Hope

Sharing stories of impact and conversations about “next time” contribute to a sense of hope!

Talking about “next time” is one way to imagine yourself in a future state. This is the most basic definition of hope. For example, asking someone “What have you learned that you can apply next time?” can prompt them to focus on future possibilities and goals, vs. ruminating on what went wrong.

Checkpoint: Stress Injury Mitigation

References

Anwar, Y. (2011, November 23). Dream sleep takes sting out of painful memories. Berkeley News. Retrieved November 29, 2023, from https://news.berkeley.edu/2011/11/23/dream-sleep/

Barncard, C. (2010, May 11). For comfort, mom’s voice works as well as a hug. University of Wisconsin–Madison. Retrieved November 29, 2023, from https://news.wisc.edu/for-comfort-moms-voice-works-as-well-as-a-hug/

BC Emergency Health Services (n.d.). Signs and Symptoms of Critical Incident Stress. Retrieved Feb 6, 2024 from http://www.bcehs.ca/health-info/support-for-bcehs-family-members/critical-incident-stress/signs-and-symptoms-of-critical-incident-stress

Seltzer, L. J., Prososki, A. R., Ziegler, T. E., & Pollak, S. D. (2012). Instant messages vs. Speech: Hormones and why we still need to hear each other. Evol Hum Behav, 33(1), 42-45.

Seltzer Leslie J., Ziegler Toni E. and Pollak Seth D. (2010). Social vocalizations can release oxytocin in humans. Proc. R. Soc. B.2772661–2666 http://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2010.0567

UVA Medical Center (n.d.). Stress Continuum Model. UVA Health Medical Centre. Retrieved November 29, 2023, from https://www.medicalcenter.virginia.edu/sites/wwp/assets/Stress%20Continuum%20Resources/Stress-Continuum-Poster_nmay-version.pdf

A state of emotional, mental and physical exhaustion brought on by prolonged or repeated exposure to stress.

acting in response to a situation, rather than creating or controlling it

creating or controlling a situation by causing something to happen rather than responding to it after it has happened.

to cause an intense and usually negative emotional reaction

a shared understanding of tasks and roles using cognitive aids and incremental goals

The use of effective communication to minimize misunderstandings and differing interpretations

staying in tune with the evolving present

the conscious knowledge of the immediate environment and all of the events happening in it

Being fair, not equal, and properly managing human resources.