Developing Risk Self Awareness

Learning Objective

To define and understand models and tools for risk awareness and self awareness as they relate to outdoor risk management.

Lemon Theory

Also referred to as “Error Chain Theory,” Lemon Theory proposes that incidents are often preceded by a chain of actions or events, each considered a “lemon.” The accumulation of lemons in the chain increases the likelihood of an incident. These lemons can be factors such as lack of sleep, route-finding errors, disagreements or interpersonal stressors, adverse weather, dehydration, or equipment damage or loss.

Each lemon can be seen as a link in a chain – one might be relatively harmless on it’s own, but as more lemons are added to the chain the likelihood of a serious incident increases. There is also a compounding effect – the more lemons are added to the chain also increases the probability of more lemons accumulating and increases the likelihood of a serious incident.

This compounding effect can be illustrated through a practical scenario:

A group of hikers sets out for a day trip, and one member realizes they forgot their map and compass (first lemon). As a result, the group encounters difficulty navigating, leading to delays and increased fatigue (second and third lemons). Due to the delays, the group misses a planned rest stop, leading to dehydration and frustration (fourth and fifth lemons). Fatigue and dehydration contribute to poor decision-making, and the group takes a wrong trail (sixth lemon). As darkness falls, the group is ill-prepared without proper lighting, further escalating the situation (seventh lemon) and increasing the probability of an accident or incident.

The compounding effect in Lemon Theory underscores the interconnected nature of incidents. Addressing and mitigating the early lemons in the chain becomes crucial to prevent a cascade of events that could lead to a more significant incident. It highlights the importance of proactive risk management and early intervention in outdoor activities to break the chain of potential challenges.

Research into incident occurrences has shown that a minimum of 4 errors had been made prior to the incident, and an average of 7 had been made by the end of the incident.

Behavioural Clues Before an Incident

Before an incident occurs, there are often behavioral clues that indicate something might be about to happen. Recognizing these clues is crucial for proactive risk management and avoiding potential incidents. Here are seven common behavioral clues adapted from the aviation industry’s “11 Clues”:

Confusion, or an “Empty Feeling”

A sense of confusion, bewilderment, or falling behind mentally. This can indicate a potential lack of knowledge, experience, or decision fatigue.

This can also be experienced as a “bad gut feeling” (more on that below.)

Fixation or Preoccupation

Focusing on one thing or event to the exclusion of everything else. Also known as “tunnel vision.” This can hinder awareness of changing environmental conditions or emerging risks.

“No One’s Driving the Bus”

This happens when there is a lack of clear leadership or control; or an assumption that someone else is in charge. This can stem from a breakdown in communication and responsibility and can also be symptomatic of the Heuristic Trap of the Expert Halo, which we will explore in more detail in a later chapter.

Departure from Standard Operating Procedures

Deviation from established procedures and norms increases the risk of incidents; often occurs under emergency conditions. Standard operating procedures help to maintain safe field practices and stable norms. When someone takes a shortcut, or “wings it,” the chance of an incident increases. Often abandoning standard operating procedures is a reaction to unusual or emergency conditions.

Ambiguity or Unresolved Discrepancies

This is a failure to resolve differing interpretations of directions or plans. Unresolved discrepancies are often not noticed until after an incident occurs. I.e. having two leaders with a different vision of where the group is going on the map. Using Closed Loop Communication as a technique to confirm understanding and align on meaning can help mitigate this effect.

Failure to Meet Targets

An inability to achieve planned goals or targets can result in making adjustments to the original plan or taking increased risks to catch up. An example of failing to meet targets is delaying lunch or skipping snacks so that you can get to a certain location by the time you stop for lunch.

Incomplete Communications

Incomplete communications are the result of withheld ideas, suggestions, questions or information. This can be mitigated by fostering a healthy Culture of Dissent within your team and using Assertive Communication strategies.

These clues often precede incidents, offering an opportunity for intervention. Recognizing these behavioral signs requires vigilance and a proactive approach to risk management. By actively monitoring and addressing these behavioral clues, individuals and teams can enhance their situational awareness and reduce the likelihood of incidents in outdoor activities.

It is important to note that many of these clues relate closely to the traps discussed in Heuristic Traps. The best way to avoid incidents is to actively seek new perspectives, stay informed about changing conditions, prioritize safety over familiarity or consistency, critically evaluate information, and make decisions based on a balanced assessment of the available information.

That “Gut Feeling”

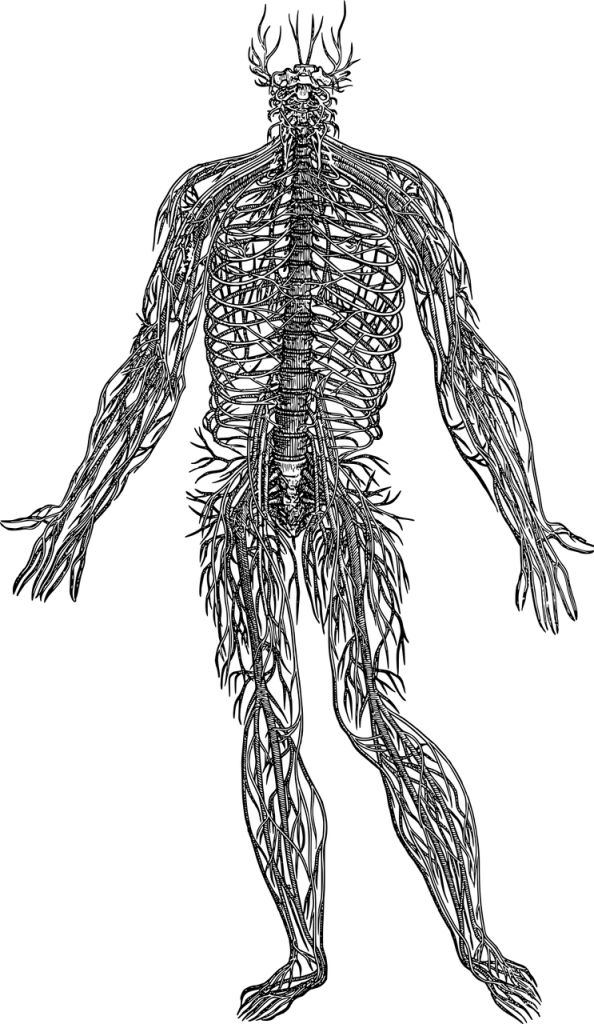

The vagus nerve, also known as the “wandering nerve,” plays a crucial role in regulating bodily functions, including the parasympathetic and sympathetic nervous systems, connecting the gut to the brain’s emotional centers. This nerve directly influences the “Fight, Flight, Freeze” response and contributes to our sense of danger.

The vagus nerve, also known as the “wandering nerve,” plays a crucial role in regulating bodily functions, including the parasympathetic and sympathetic nervous systems, connecting the gut to the brain’s emotional centers. This nerve directly influences the “Fight, Flight, Freeze” response and contributes to our sense of danger.

The vagus nerve’s extensive distribution, especially through the gut, contributes to the sensation of emotions in the stomach or belly. Emotional responses, including the sense of danger, originate from the vagus nerve, linking the unconscious brain to the body.

Emotional processing is not limited to the brain; the enteric nervous system (ENS) in the gut, often called the “second brain,” communicates with the central nervous system. The “gut feeling” is a result of the intricate connection between the ENS, vagus nerve, and the brain’s amygdala.

The amygdala, also known as the “lizard brain” is the brain region responsible for emotional responses, governing survival instincts. Gut feelings can trigger the body’s immediate responses without involving the cognitive, thinking brain.

In the book “Thinking – Fast and Slow,” Daniel Kahneman’s concept of System 1 (intuitive, fast) and System 2 (logical, slow) thinking helps understand the interplay between gut reactions and rational thought. System 1 thinking falls into the category of gut feelings and responses; it is unconscious and happens instantaneously. System 2 thinking on the other hand is a function of the rational, logical parts of the brain; it takes conscious effort and more time. It can be helpful to get into the habit of checking our System 1 ‘gut reactions’ with System 2 thinking, in order to avoid acting on partial information.

Your “gut feeling,” especially when trained, can be a way for your body and senses to signal that there is a danger or risk that may be too complex to think through in the moment. Your gut feeling should only be relied upon as a ‘red flag’ or early warning, telling you it is time to pause and engage your System 2 thinking skills. While valuable, relying solely on gut feelings may lead to misjudgments, especially when faced with new activities or environments or when relying on judgements that are based solely on prior experiences (see section on Non-Event Feedback).

This distinction contributes to the differences between Real and Perceived Risk which are often in play in the outdoors. It is also important to note that a lack of gut feeling does not mean there is not danger present.

Video – The Fight Flight Freeze Response

Watch the video below, which further explains how our “Fight, Flight, Freeze” response works.

Harnessing Your Gut Feelings

Developing and harnessing your gut feelings is a valuable skill in outdoor leadership. It involves being attuned to subtle signals and emotional responses. Here’s a guide on how to enhance your intuitive processes:

- Notice It:

- Question: What am I feeling or sensing?

- Practice: Tune into your feelings and thoughts. Practice mindfulness and tactical breathing techniques to heighten awareness of your emotional and sensory responses.

- Look Around:

- Question: What is objectively happening around me that triggers this feeling?

- Investigate: Identify the source of the alarm. Understand the external factors contributing to your gut feeling.

- Re-Evaluate:

- Questions: Is there actual danger? Why am I experiencing this gut feeling? What specific aspects of the situation raise concerns?

- Critical Thinking: Assess whether the perceived danger aligns with reality. Explore the reasons behind your gut feeling and evaluate the situation objectively.

- Be Cautious if Dismissing:

- Self-Reflection: If choosing to dismiss the gut feeling, question why. Consider whether heuristic traps or biases might be influencing your decision. Heed caution when ignoring intuitive warnings.

- Next Steps:

-

- Questions: What are my next steps?

- Decision-Making: Determine a course of action based on your evaluation. Plan how to navigate the situation considering the information gathered.

It’s important to discuss your intuitions with your team. Often a gut feeling is shared by multiple people, and only after an incident does it comes to light that no one spoke up about it. Discussing intuitions collectively enhances overall situational awareness.

Pausing to check in with others to get more brains engaged in System 2 thinking can turn up new information and perspectives. Two brains are better than one!

Engage in Reflective Practice after the fact by seeking feedback and guidance from experienced individuals in areas where you want to improve your intuition and judgement, as learning from others’ insights and experiences can be a valuable part of honing your perceptive skills in risk environments.

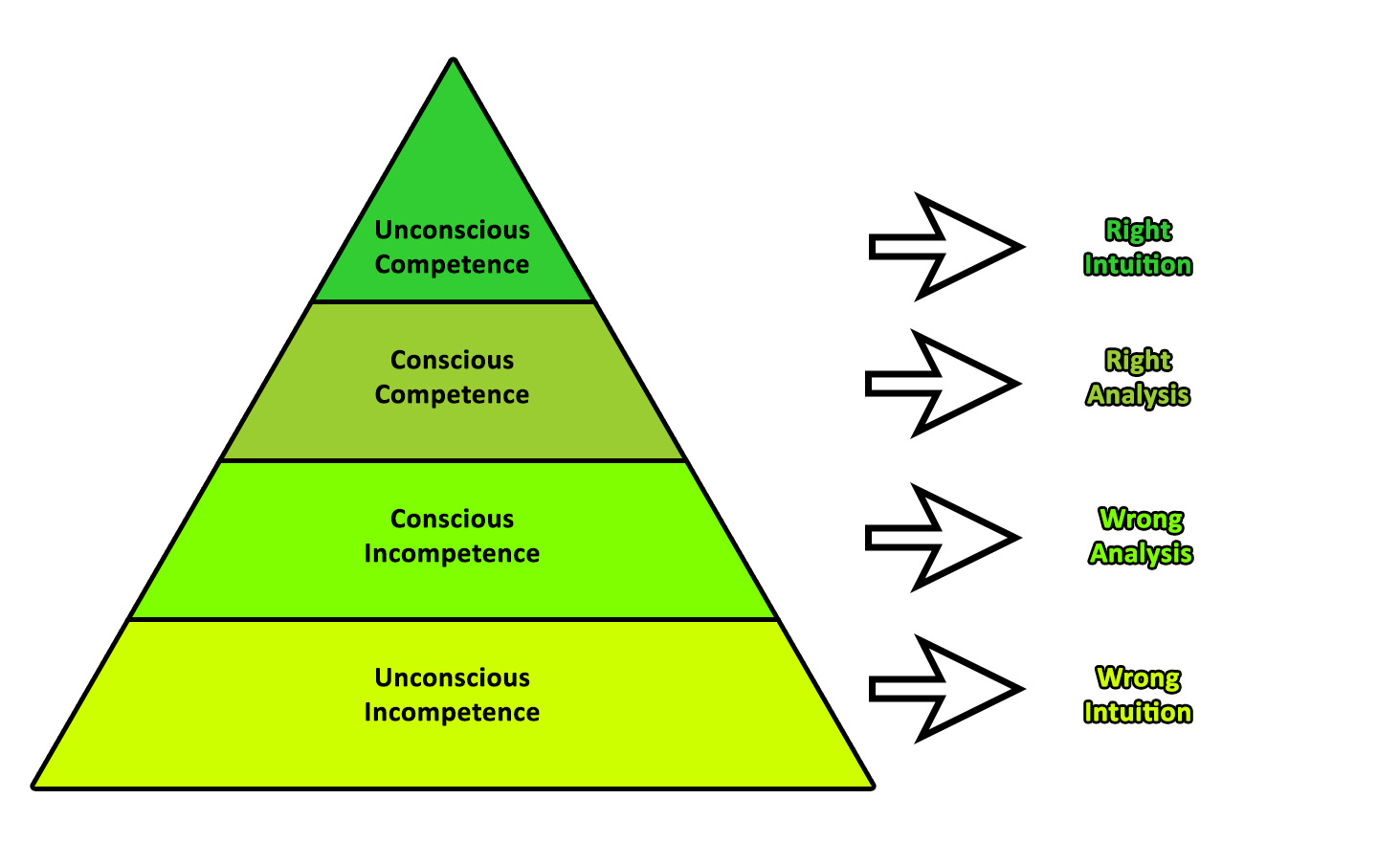

The Four Stages of Competence

“…the hallmark of an expert is not that she has reached a level of subconscious heuristic processing. It is that she has developed the intentional practice of self-reflection that allows her to understand why she subconsciously chose to follow or ignore the heuristic at hand. It is this willingness to question one’s underlying decision-making processes that allows one to truly become an expert.”

— Gates Richards and Tod Schimelpfenig, “Comments on the ‘Levels of Expertise Matrix’”

The Four Stages of Competence is largely credited to Martin M. Broadwell, who first discussed it in the late 1960’s. The Four Stages were originally known as the “Conscious Competence Learning Model.”

Unconscious Competence

Being fluent in an area or able to use a skill without having to devote much conscious attention to it. Unconscious Competence is associated with reliable intuitions in relation to the area or skill.

Conscious Competence

Having some level of fluency with a specific area or skill, along with some level of awareness of one’s level of ability. Conscious Competence is associated with the development of sound analytic skills in the area.

Conscious Incompetence

Being consciously aware of one’s lack of skill or understanding in relation to a specific area or skill. Conscious Incompetence is often marked by poor analytical abilities in the area.

Unconscious Incompetence

Being unaware of an area or skill and/or not being aware of one’s lack of competence in an area or skill. Unconscious Incompetence is associated with poor intuitions in relation to that area or skill.

The Four Stages As Tool

In outdoor leadership this model is a helpful tool that can help us develop self awareness as we grow through our career. Being able to accurately identify (sometimes with the help of others) what we know and don’t know is a key skill – the goal is to move between the upper three areas and steer clear of the unconsciously incompetent end of the spectrum when we are working in risk environments. This is a key component of Risk Self Awareness and maintaining a growth mindset.

Once one reaches the level of “Unconscious Competence” in a given area there are two choices – to move towards Mindful – Reflective Competence, or towards Complacency – Complacent Competence. Reflective practice moves us towards true mastery (Reflective Competence) where we actively reflect on not only the decisions we make but also the decision making-process and ask questions like, “were we good or were we lucky,” continuously learning and growing. Without reflecting and asking questions about the quality of the decision-making process along with the decisions made we risk becoming unaware of areas of incompetence, and opt out of learning/growing/improving towards Complacent Competence.

Complacency in Relation to Four Stages of Competence

An article written by Gates Richards and Tod Schimelpfenig brings to light some of the flaws of this Stages of Competence Model: primarily in the idea of “subconscious competence as a hallmark of an expert”. This is the idea that once we have reached expert level in said industry, we no longer have to “think” to be good.

“It may be harmful if the expert is unaware of the reasons for their actions and falls prey to the causality fallacy—the assumption that their actions produced the positive results.”

This is problematic in that we want our experts to be self-aware and intentional in all their actions.

As educators, we should strive for reflective competence. The ability to intentionally develop our own judgment, and to pass on the lessons we have learned to our students requires that we spend time reflecting on our decision-making process. How can we expect to teach others if we cannot articulate what we ourselves have experienced?

In our opinion, the hallmark of an expert is not that she has reached a level of subconscious heuristic processing. It is that she has developed the intentional practice of self-reflection that allows her to understand why she subconsciously chose to follow or ignore the heuristic at hand. It is this willingness to question one’s underlying decision-making processes that allows one to truly become an expert.

Once an individual enters the cycle of mindfulness, she becomes a much better student and educator.

Checkpoint: True or False

References

Breit S, Kupferberg A, Rogler G and Hasler G .(2018). Vagus Nerve as Modulator of the Brain–Gut Axis in Psychiatric and Inflammatory Disorders. Frontiers in Psychiatry. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00044/full

Davis, B., & Francis, K. (2023). “Conscious Competence Model of Learning” in Discourses on Learning in Education. https://learningdiscourses.com/discourse/conscious-competence-model-of-learning/

Gates, R., & Schimelpfenig, T. (2010, November). Comments on the “Level of Expertise Matrix”. NOLS. https://www.nols.edu/media/filer_public/68/7d/687d3a9e-ac00-43f2-8b1f-14370ee9de99/judgement_and_decision_making_-_comments_on_the_levels_of_expertise_model_schimelpfenig-richards.pdf

Kahneman, D. (2013). Thinking, Fast and Slow. Doubleday Canada.

Mains, R. (2013, October 3). My 2 Cents Worth – Breaking the Error Chain. Just Helicopters. https://justhelicopters.com/Articles-and-News/Community-Articles/Article/67494/My-2-Cents-Worth-Breaking-the-Error-Chain

Menakem, R. (2017). My Grandmother’s Hands: Racialized Trauma and the Pathway to Mending Our Hearts and Bodies (pp. 138-139). Central Recovery Press.

An Expert Halo happens when the leader of a party has been elected based on age or perceived ability, but not experience or know how. Novices are likely to follow the leader without question, resulting in issues.

A Culture of Dissent emerges when a group becomes comfortable asking for clarification when something doesn’t initially make sense or an instruction is counterintuitive or unclear.

A heuristic is a mental shortcut that facilitates quick decision making. A heuristic trap occurs when we make a decision without considering all of the information available.