Outcome vs. Decision

Learning Objective

To explore three common pitfalls that impact decision making; non-event feedback, confirmation bias and complacency.

To introduce key reflective tools to help guide and understand decision making in risk environments.

Introduction

As we’ve explored so far, part of good risk management behaviour stems from our ability to understand our scope of practice (what we are skilled and qualified to do), and the best practices and parameters of the activities we are leading. Risk management policies and procedures are in place for this reason – they can be used as agreed-upon handrails to dictate safe practices in the field. Clear policies eliminate the need for complex decision making in areas where there is a ‘best practice’ or accepted industry standard – examples being to wear a Personal Floatation Device (PFD) while doing paddle sports, or to wear a helmet while riding a bike.

However, leading groups in the outdoors is a highly complex and dynamic task – one where applying a principles-based approach to decision making is a critical skill. We cannot always predict how things will unfold in the outdoors, and no two situations will ever be alike; therefore even the best written policies and procedures will never cover all the scenarios that can arise. Beyond understanding and following policies and best practices, the most important skills to develop in risk management are adaptive critical thinking skills – including honing our decision making skills and consciously developing judgement.

Let’s take a look at how we make decisions, and how feedback (or a lack of feedback) effects our future decision making.

Non-Event Feedback

In outdoor leadership, decision-making is a critical skill, often evaluated based on outcomes. However, the lack of significant negative events, termed Non-Event Feedback, can mislead decision-makers into assuming success without a thoughtful reflection and analysis. We tend to take non-event feedback as positive feedback about our decision making and skill, thus we are likely to repeat those same types of decisions again. Understanding the challenges posed by non-event feedback is essential for enhancing decision-making in dynamic outdoor environments.

Non Event Feedback can create a false sense of confidence in decision-making. Outdoor settings involve high stakes and poor feedback loops, making evaluating the quality of decisions challenging.

A Non-Event Feedback Scenario:

A group of paddlers decide to make a crossing late in the day, in building seas in order to get to a coveted campsite. Despite the rough conditions, they safely arrive at the other side of the crossing, and are able to set up camp and have a nice meal. They decide that it was a good decision to do the crossing in those conditions.

What they did not consider in their evaluation of the decision are the ‘what ifs’.

- What if they had been delayed on the crossing by a few minutes?

- What if there had been equipment failure mid-crossing, a dropped water bottle, paddler fatigue, worsening conditions, boat traffic, or any number of other circumstances that could have slowed the group down or caused an incident?

In reality, our margins for error in the outdoors can be quite minimal, making it challenging to distinguish between good decision-making and chance.

Non-event feedback poses challenges to decision-makers in outdoor leadership, creating a potential unseen area in evaluating the quality of decisions. Acknowledging the complexities of outdoor environments, considering ‘what-if’ scenarios, and fostering a reflective mindset are crucial steps toward improving decision-making skills. By navigating the pitfalls of non-event feedback, leaders can enhance risk awareness, and make decisions that prioritize both success and safety in dynamic outdoor settings.

Confirmation Bias

Confirmation bias is a common cognitive tendency in individuals to seek information that aligns with their existing beliefs while disregarding or downplaying conflicting evidence. This bias can significantly impact decision-making processes, leading to the reinforcement of pre-existing attitudes and beliefs. Recognizing and mitigating confirmation bias is crucial for fostering objective and well-informed decision-making.

An everyday example of confirmation bias can be found in an avid hockey fan who believes that the league’s referees do not like their chosen team. When a call is made against their team, the individual will place more weight on the decision, seeing it as “evidence” that the referees are against their team (whether the call was warranted or not). An objective observer with knowledge of the game and without confirmation bias would be able to note whether the call was just.

Confirmation bias can also come out of positive events and reactions. If while on a hike an individual approaches a wild animal and is able to interact with it peacefully using a technique they learned online, they may begin to believe that since their actions resulted in a “good” outcome that it was the correct decision, and that their actions were correct.

In a professional or group environment, the culture surrounding mistakes and learning can influence individuals’ willingness to openly discuss decision-making errors. A culture that encourages learning from mistakes empowers people to speak up and reflect on decisions, fostering a safer and more informed decision-making process. We will explore this further in the chapter on Honouring Mistakes.

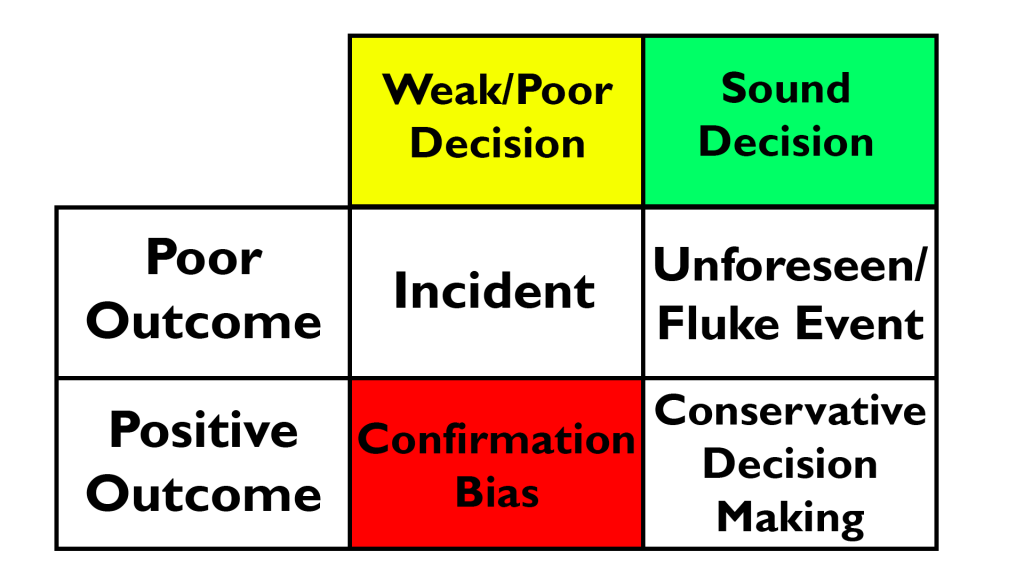

Outcome vs Decision – A Reflective Decision Making Tool

The following shows the “Outcome vs Decision” Quadrant. This model can be used to reflect on and evaluate decisions. Most case studies that we use to look at risk management in the outdoors (the STS avalanche tragedy is an example) are based on the Weak/Poor Decision ~ Poor Outcomes quadrant. This is where we tend to focus discussions and reflections; “What went wrong that resulted in this poor outcome?” While it can be helpful to learn from these incidents, developing a reflective practice to evaluate our decisions regardless of outcome can be a powerful tool to improve our decision making ability.

Match the images: Decision vs. Outcome

Solution

Conservative Decision Making – Positive Outcome:

- In this quadrant, decisions made were conservative, emphasizing safety and risk mitigation. The positive outcome suggests that the decisions aligned with best practices, policies, and safety protocols.

Conservative Decision Making – Poor Outcome:

- Despite making conservative decisions, the outcome was poor. This quadrant prompts reflection on external factors or unforeseen circumstances that might have influenced the outcome negatively.

Risky Decision Making – Positive Outcome:

- This quadrant involves making decisions that carry some level of risk, but the outcome turns out positive. Reflection is essential to understand what factors contributed to the favorable result despite taking risks.

Risky Decision Making – Poor Outcome:

- Here, decisions involved taking risks, and the outcome was poor. This quadrant offers a critical learning opportunity, however one we try to avoid by situating ourselves in the Conservative Decision Making quadrant.

Evaluating Decisions by Using Reflective Practice

Reflective Practice is a tool that extends beyond analyzing negative outcomes; it is equally applicable to scenarios with positive results. Engaging in Reflective Practice by routinely asking ourselves if a positive outcome was because of, or despite, the decisions we made allows us to avoid the pitfalls of confirmation bias and non-event feedback.

Reflective Practice is part of nurturing a growth mindset. In the context of outdoor leadership and risk management, integrating Reflective Practice into one’s approach allows for the development of self-observation, self-evaluation skills, and the cultivation of sound decision-making abilities.

For example: if you had a really bad day, but was given the opportunity to jump in a time machine to re-do the day again, the process of thinking about that experience, figuring out what you want to change, how to to make it better, and what you want to repeat is Reflective Practice.

It is still valuable to go through a reflective practice when things go well. The theory of Non-Event Feedback informs us that just because the outcome was benign, it does not mean that the decision was sound. Analyzing why something was successful helps us uncover what we did well, as well as potentially uncovering biases and decision making tendencies. It can tell us when we were indeed “good” and not just “lucky”, so we can build on and improve future decision-making processes.

A Simple Reflective Practice Model

A simple Reflective Practice exercise can be done using the “What?” | “So What?” | “Now What?” model originally established by teacher and writer Terry Borton in 1970.

This is a common model for debriefing experiential based activities, and transfers smoothly to be used by leaders to guide self reflective practice.

|

What?What? Recalling and describing the events or experiences. It’s about providing a detailed account of what happened. What were the key actions, decisions, or events? |

|

So What?This phase delves into the significance and meaning of the experiences. Why do these events matter? What were the implications or consequences of certain actions or decisions? |

|

Now What?This phase focuses on the actionable insights and lessons learned. What can be done differently in the future based on the reflections? It prompts the development of an action plan for improvement. |

Complacency

“Complacency is a state of mind that exists only in retrospective: it has to be shattered before being ascertained.”

— Vladimir Nabokov

Complacency is defined as an uncritical satisfaction with oneself or one’s achievements. In the context of outdoor leadership, complacency can be an unnoticed factor that may lead us to make mistakes and, ultimately, result in incidents.

When we do not engage in reflective practice and are unaware of the quality of our decisions, we may assume that a decision was sound merely because no incident occurred. Consequently, there is a risk of unconsciously or consciously opting out of learning, growing, and improving if we perceive ourselves as “good” rather than attributing success to mere luck.

As prudent leaders responsible for the lives of others, it is our duty to continuously reflect on the decisions we make. Noting the nuances and differences of each situation enables us to adapt and refine our critical thinking skills with each subsequent decision-making opportunity.

Without reflecting on and reviewing our practices, we are likely to become complacent over time. While there may be no final stage of mastery where all decisions are perfect and free of faults, we must strive towards a reflective mastery. This involves constantly adjusting our opinions and decisions as more information is gathered. By maintaining a “beginner’s mind” and developing a growth mindset, we retain the ability to continuously learn and grow within our discipline. This frees us from the trap of doing things simply because we have done them that way before.

Reflection

“We do not learn from experience… we learn from reflecting on experience.”

— John Dewey

Checkpoint: Reflection Exercise

Reflection on past decisions and events is important for learning and raising competence. When reflecting, it’s important to be as impartial and open minded as possible.

Remember a specific time on a past trip, expedition, or experience where you made a risk management decision and guide yourself through reflection with the following questions. This is not an exhaustive list, but these questions will help you begin the process.

Remember, reflective practice is a personal practice that can vary greatly for different contexts: these are a few suggestions specific to analyzing decision making.

1. Was the outcome positive because of or despite the decisions made?

-

- Is there a direct connection between the quality of decision and the outcome, or would the same outcome have happened with a different decision?

2. What other possible outcomes could have happened with this same decision?

-

- Play “what if” and imagine things hadn’t gone as planned. Do your decisions still hold up?

3. How did you come up with the decision you made?

-

- Think about the process of coming to the decision – what factors did you consider and how did these play into making your decision?

- What factors do you see now that you did not consider?

- Would these have changed your decision?

- Were there other factors unrelated to the risk that were swaying your decision?

4. What other possible decisions could have been made instead?

-

- Were these discussed at the time, or are they in hindsight?

5. Did you learn anything from this that you would add to your decision-making process next time?

References

(2023, July 23). Self-complacency, n. Oxford English Dictionary. https://doi.org/10.1093/OED/7290956228

Carpenter, S. (2020). Building and Evaluating Decision Making Skills [American Avalanche Institute WRMC 2020 Presentation].

Gates, R., & Schimelpfenig, T. (2010, November). Comments on the “Level of Expertise Matrix”. NOLS. https://www.nols.edu/media/filer_public/68/7d/687d3a9e-ac00-43f2-8b1f-14370ee9de99/judgement_and_decision_making_-_comments_on_the_levels_of_expertise_model_schimelpfenig-richards.pdf

Schoel, J., Prouty, D., & Radcliffe, P. (1988). Island of healing : a guide to adventure based counseling. Project Adventure.

The ability to review actions you took and the outcomes they produced to learn from, and to move towards future growth.

The thought process that if nothing bad happened last time a decision was made, the same decision is sound and nothing bad will happen this time, either.