9.2: Types of Procurement Contracts

The contract award takes place after the bid closes, and the contract document will depend on the type of bid solicitation.

Contract Types

Understanding a little bit about the major kinds of contracts available for procurement is essential to choosing the one that creates the most fair and workable deal for the organization and the supplier. Some contracts are fixed price: no matter how much time or effort goes into them, the client always pays the same. Some contracts are cost-reimbursable, also called cost plus. This is where the seller charges the client for the cost of doing the work plus a fee or rate. The third major kind of contract is time and materials. That’s where the client pays a rate for the time spent working on the project and also pays for all the materials used to do the work.

Public Procurement Playbook

Watch this video to learn more about the different types of contracts offered by the government to vendors and suppliers.

Source: County Office Law. (2024, April 17). What Are the Different Types of Government Contracts. [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/u3r9Bu2OaXk

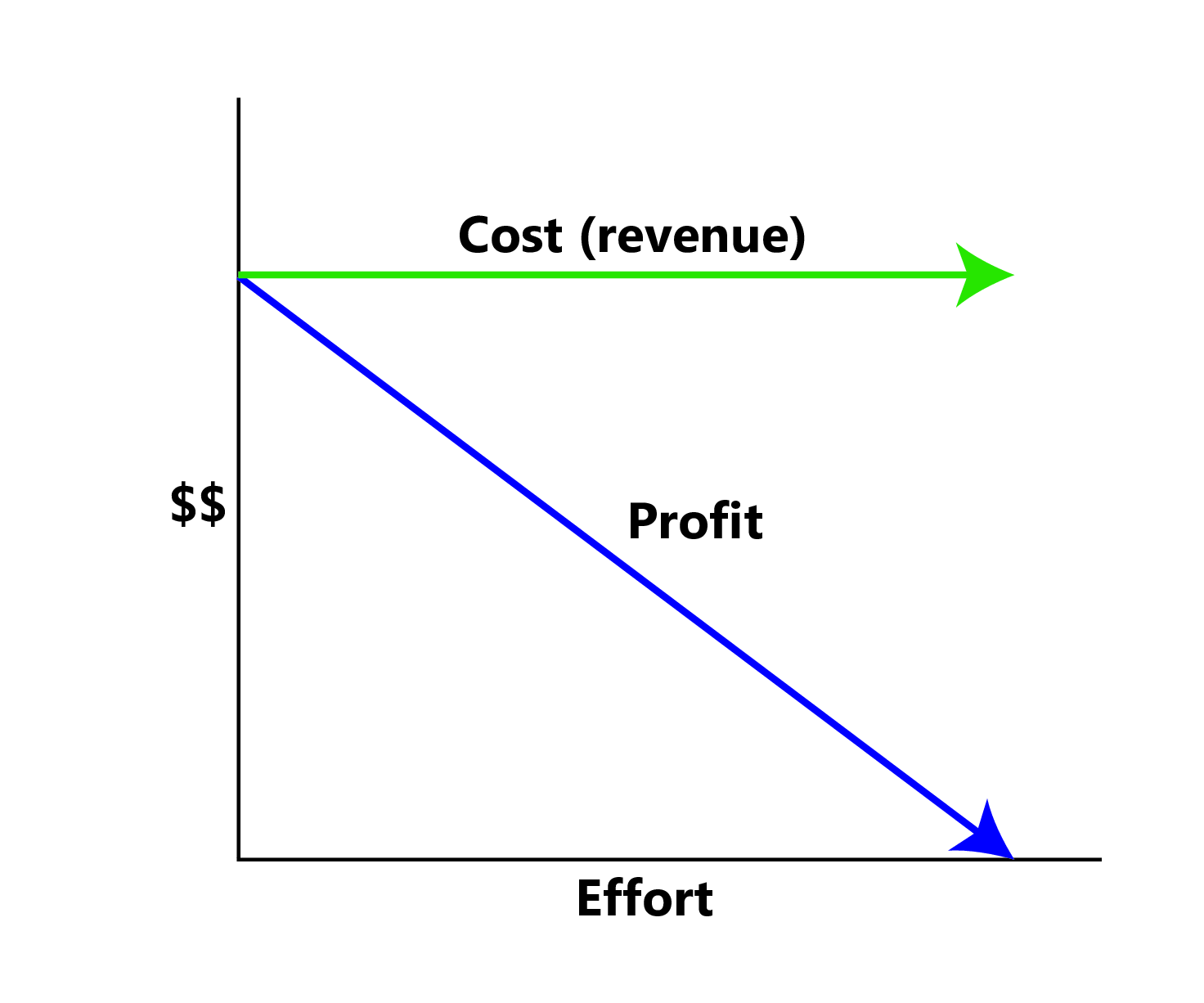

Fixed-Price Contracts

A fixed-price contract is a legal agreement between the project organization and an entity (person or company) to provide goods or services to the project at an agreed-on price. The contract usually details the quality of the goods or services, the timing needed to support the project, and the price for delivering goods or services. There are several variations of the fixed-price contract. For commodities, goods, and services where the scope of work is very clear and not likely to change, the fixed-price contract offers a predictable cost. The responsibility for managing the work to meet the project's needs is focused on the contractor. The project team tracks the quality and progress of the project to ensure the contractors are meeting the project’s needs. The risks associated with fixed-price contracts are the costs associated with project change. If a change occurs on a project that requires a change order from the contractor, the price of the change is typically very high. Even when the price for changes is included in the original contract, changes on a fixed-price contract will create higher total project costs than other forms of contracts because the majority of the cost risk is transferred to the contractor, and most contractors will add a contingency to the contract to cover their additional risk.

In Exhibit 9.1 the cost to the client stays the same, but as more effort is exerted, the profit to the contractor goes down.

Fixed-price contracts require the availability of at least two or more suppliers with the qualifications and performance histories that ensure the needs of the project can be met. The other requirement is a scope of work that will most likely not change. Developing a clear scope of work based on good information, creating a list of highly qualified bidders, and developing a clear contract that reflects that scope of work are critical aspects of a good fixed-priced contract.

If the service provider is responsible for incorporating all costs, including profit, into the agreed-on price, it is a fixed-total-cost contract. The contractor assumes the risks for unexpected increases in labour and materials needed to provide the service or materials, and in the materials, and timeliness needed.

The fixed-price contract with price adjustment is used for unusually long projects that span years. The most common use of this type of contract is the inflation-adjusted price. In some countries, the value of the local currency can vary greatly in a few months, which affects the cost of local materials and labour. In periods of high inflation, the client assumes the risk of higher costs due to inflation, and the contract price is adjusted based on an inflation index. The volatility of certain commodities can also be accounted for in a price-adjustment contract. For example, if the price of oil significantly affects the costs of the project, the client can accept the oil price volatility risk and include a provision in the contract that would allow the contract price to be adjusted based on a change in the price of oil.

The fixed-price contract with an incentive fee provides an incentive for performing the project above the established baseline in the contract. The contract might include an incentive for completing the work on an important milestone for the project. Often, contracts have a penalty clause if the work is not performed according to the contract. For example, if new software is not completed in time to support the implementation of training, the contract might penalize the software company by charging a daily amount for every day the software is late. This type of penalty is often used when a deliverable is critical to the project, and the delay will cost the project significant money.

If the service or materials can be measured in standard units, but the amount needed is not known accurately, the price per unit can be fixed—a fixed-unit-price contract. The project team assumes the responsibility of estimating the number of units used. If the estimate is inaccurate, the contract does not need to be changed, but the project will exceed the budgeted cost.

Table 9.1 shows the various fixed price contracts and their characteristics.

| Type | Known Scope | Share of Risk | Incentive for Meeting Milestones | Predictability of Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed total cost | Very high | All contractor | Low | Very high |

| Fixed unit price | High | Mostly project | Low | High |

| Fixed price with incentive fee | High | Mostly project | High | Medium-high |

| Fixed price with price adjustment | High | Mostly project | Low | Medium |

Cost-Reimbursable Contracts

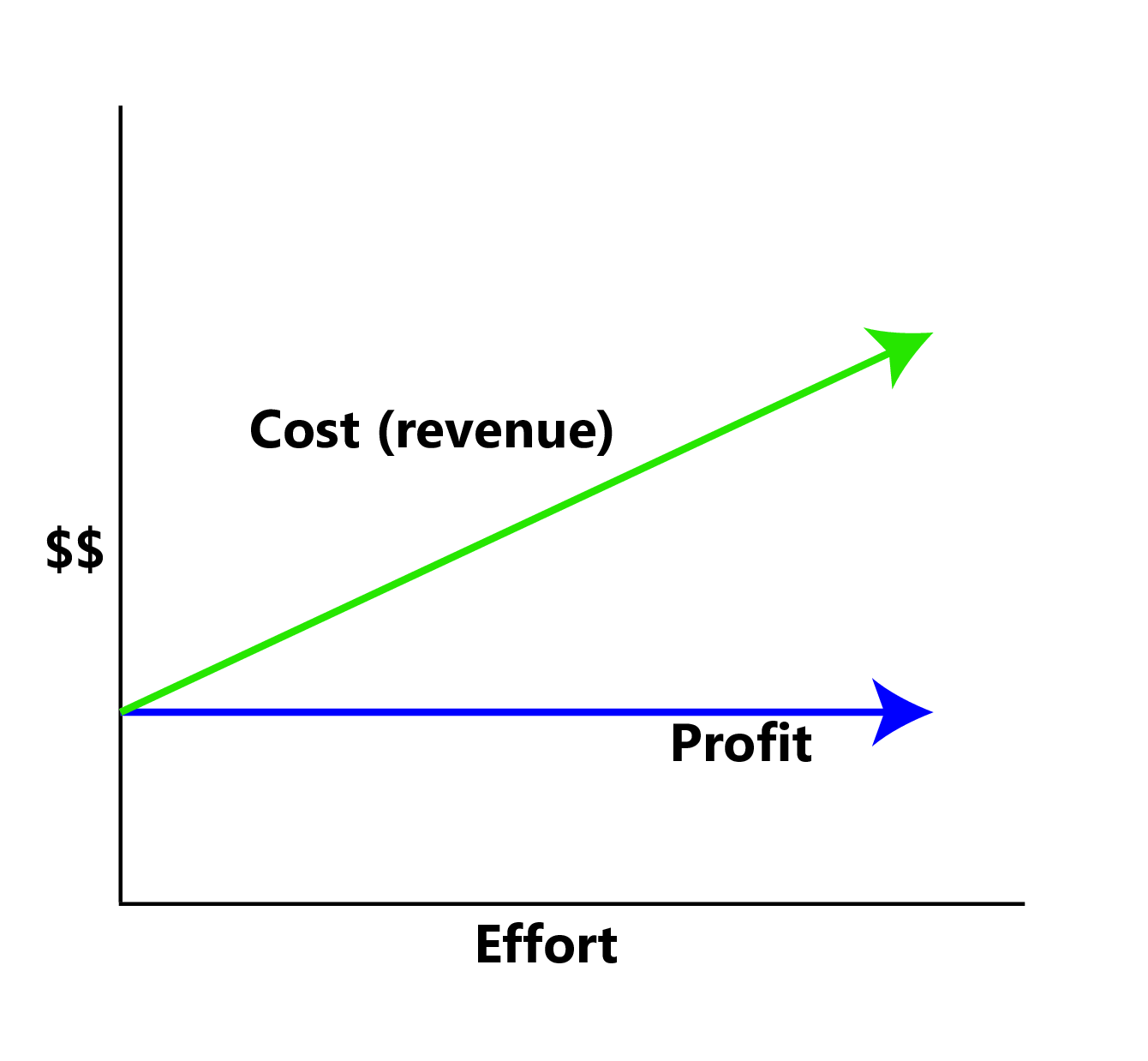

In a cost-reimbursable contract, the organization agrees to pay the contractor for the cost of performing the service or providing the goods. Cost-reimbursable contracts are also known as cost-plus contracts. Cost-reimbursable contracts are most often used when the scope of work or the costs for performing the work are not well known. The project uses a cost-reimbursable contract to pay the contractor for allowable expenses related to performing the work. Since the cost of the project is reimbursable, the contractor has much less risk associated with cost increases. When the costs of the work are not well known, a cost-reimbursable contract reduces the amount of money the bidders place in the bid to account for the risk associated with potential increases in costs. The contractor is also less motivated to find ways to reduce the cost of the project unless there are incentives for supporting the accomplishment of project goals.

Exhibit 9.2 shows that as efforts increase, costs to the client go up, but the contractor’s profits stay the same.

Cost-reimbursable contracts require good documentation of the costs that occurred on the project to ensure that the contractor gets paid for all the work performed and to ensure that the organization is not paying for something that was not completed. The contractor is also paid an additional amount above the costs. There are several ways to compensate the contractor.

- A cost-reimbursable contract with a fixed fee provides the contractor with a fee, or profit amount, that is determined at the beginning of the contract and does not change.

- A cost-reimbursable contract with a percentage fee pays the contractor for costs plus a percentage of the costs, such as 5% of total allowable costs. The contractor is reimbursed for allowable costs and is paid a fee.

- A cost-reimbursable contract with an incentive fee is used to encourage performance in areas critical to the project. Often, the contract attempts to motivate contractors to save or reduce project costs. Using the cost-reimbursable contract with an incentive fee is one way to motivate cost-reduction behaviours.

- A cost-reimbursable contract with an award fee reimburses the contractor for all allowable costs plus a fee that is based on performance criteria. The fee is typically based on goals or objectives that are more subjective. An amount of money is set aside for the contractor to earn through excellent performance, and the decision on how much to pay the contractor is left to the judgment of the project team. The amount is sufficient to motivate excellent performance.

Table 9.2 shows the various cost-reimbursable contracts and their characteristics.

| Cost Reimbursable (CR) | Known Scope | Share of Risk | Incentive for Meeting Milestones | Predictability of Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CR with fixed fee | Medium | Mostly project | Low | Medium-high |

| CR with percentage fee | Medium | Mostly project | Low | Medium-high |

| CR with incentive fee | Medium | Mostly project | High | Medium |

| CR with award fee | Medium | Mostly project | High | Medium |

| Time and materials | Low | All project | Low | Low |

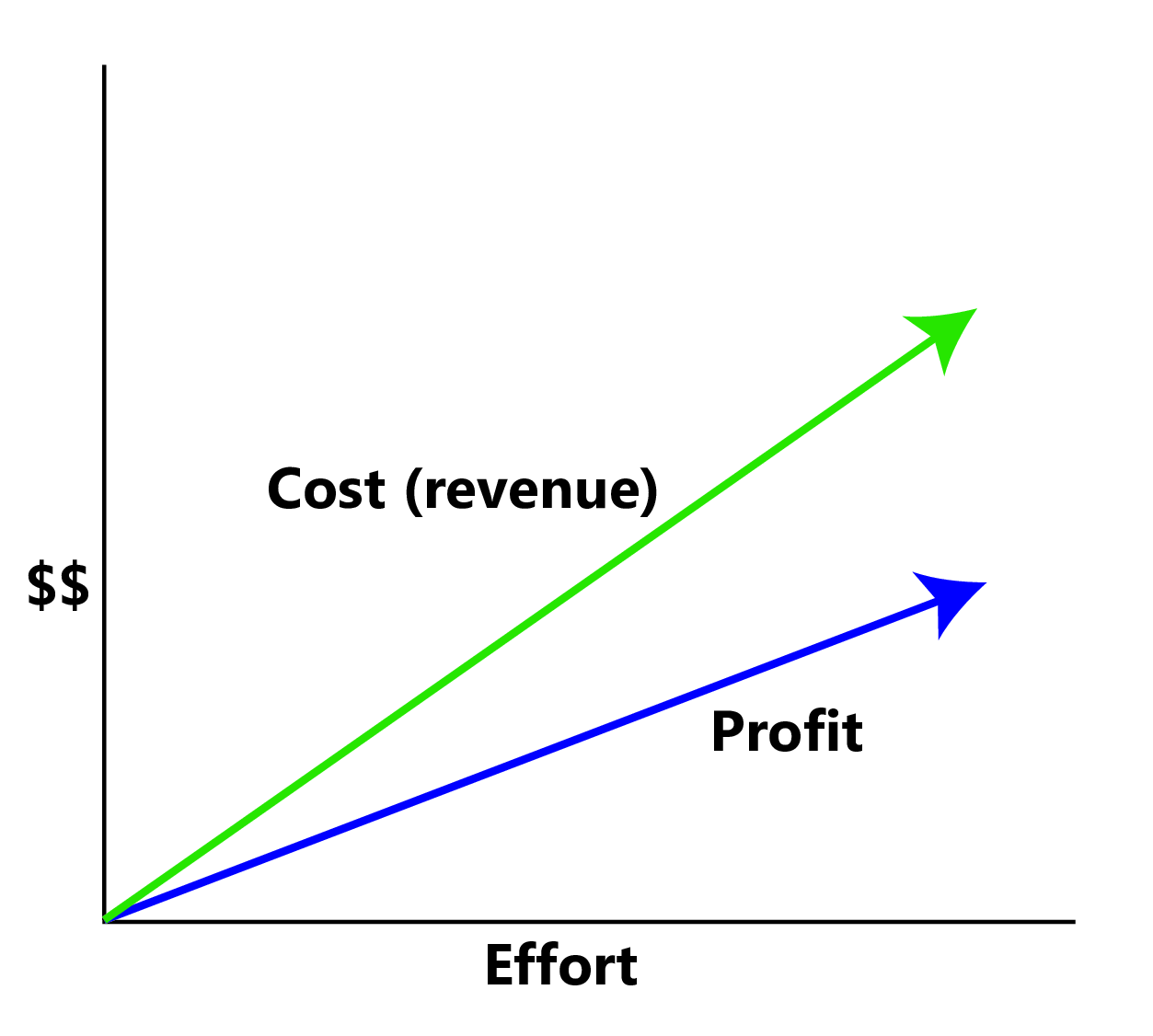

Time and Materials Contract

On small activities with high uncertainty, the contractor might charge an hourly rate for labour, plus the cost of materials, plus a percentage of the total costs. This type of contract is called time and materials (T&M) contract. Time is usually contracted at an hourly rate, and the contractor usually submits time sheets and receipts for items purchased on the project. The project reimburses the contractor for the time spent based on the agreed-on rate and the actual cost of the materials. The fee is typically a percentage of the total cost.

Exhibit 9.3 shows that as costs to the client go up, so does the profit for the contractor.

T&M contracts are used on projects for work that is smaller in scope and has uncertainty or risk. The project, rather than the contractor, assumes the risk. Since the contractor will most likely include a contingency in the price of other types of contracts to cover the high risk, T&M contracts provide a lower total cost to the project.

To minimize the risk to the project, the contractor typically includes a not-to-exceed amount, which means the contract can only charge up to the agreed amount. The T&M contract allows adjustments to the project as more information is available. The final cost of the work is not known until sufficient information is available to complete a more accurate estimate.

Progress Payments and Change Management

Vendors and suppliers usually require payments during the life of the contract. On contracts that last several months, the contractor will incur significant costs and will want the project to pay for these costs as early as possible. Rather than wait until the end of the contract, a schedule of payments is typically developed as part of the contract and is connected to the completion of a defined amount of work or project milestones. These payments, made before the end of the project and based on the progress of the work, are called progress payments. For example, the contract might include a payment schedule that pays for the design of the curriculum, then the development of the curriculum, and then a final payment is made when the curriculum is completed and accepted. In this case, three payments would be made. There is a defined amount of work to be accomplished, a time frame for accomplishing that work, and a quality standard the work must achieve before the contractor is paid for the work.

Just as the project has a scope of work that defines what is included in the project and what work is outside the project, vendors and suppliers have a scope of work that defines what they will produce or supply to the company. (Partners typically share the project scope of work and may not have a separate scope of work.) Often, changes in the project require changes in the contractor’s scope of work. How these changes will be managed during the life of the project is typically documented in the contract. Capturing these changes early, documenting what changed and how the change impacted the contract, and developing a change order (a change to the contract) is important to maintaining the progress of the project. Conflict among team members may arise when changes are not documented or when the team cannot agree on a change. Developing and implementing an effective change management process for contractors and key suppliers will minimize this conflict and the potential negative effect on the project.

Selecting the Contract Approach

The technical teams typically develop a description of the work that will be outsourced. From this information, the project management team answers the following questions:

- Is the required work or materials a commodity, customized product or service, or unique skill or relationship?

- What type of relationship is needed: supplier, vendor, or partnership?

- How should the supplier, vendor, or potential partner be approached: RFQ, RFP, or personal contact?

- How well known is the scope of work?

- What are the risks, and which party should assume which types of risk?

- Does the procurement of the service or goods affect activities on the project schedule’s critical path, and how much float is there on those activities?

- How important is it to be sure of the cost in advance?

The procurement team uses the answers to the first three questions listed above to determine the approach to obtaining the goods or services and the remaining questions to determine what type of contract is most appropriate.

A key factor in selecting the contract approach is determining which party will take the most risk. The team determines the level of risk that the project team will manage and what risks will be transferred to the contractor. Typically, the project management team wants to manage the project risk. Still, in some cases, contractors have more expertise or control that enables them to better manage the risk associated with the contracted work.

Checkpoint 9.2

Image Descriptions

Exhibit 9.1: The image is a chart illustrating the relationship between Effort, Cost (revenue), and Profit. It features a simple line graph with a vertical and horizontal axis. The vertical axis is labeled with dollar signs "$$", representing monetary value. The horizontal axis is labeled "Effort," indicating the amount of work or resources expended. A green horizontal line near the top of the graph extends from the vertical axis and is labeled "Cost (revenue)." This line suggests a fixed or constant revenue level over time. A blue diagonal line labeled "Profit" starts near the top of the vertical axis and slopes downward to the right, showing a decline in profit as effort increases.

[back]

Exhibit 9.2: The image is a graph illustrating the relationship between effort, cost (revenue), and profit. The horizontal axis represents "Effort," and the vertical axis shows "$$," indicating monetary values. Two lines are depicted: a green line labeled "Cost (revenue)" that rises diagonally, suggesting that cost increases with effort, and a blue line labeled "Profit" that runs horizontally, implying constant profit regardless of effort. The green line has an upward arrow, and the blue line has a rightward arrow.

[back]

Exhibit 9.3: The image is a chart illustrating the relationship between effort, cost (revenue), and profit. The chart features two lines: a green line representing cost (revenue) and a blue line representing profit. Both lines originate from the same point at the bottom left of the graph, near an "Effort" axis (horizontal) and a "$$" axis (vertical) intersection. The green line ascends at a steeper angle than the blue line, indicating that as effort increases, cost rises more sharply compared to profit. This reflects a scenario of diminishing returns, where additional effort leads to higher costs that increase faster than profits.

[back]

Attributions

"Chapter 7: Project Procurement" in Essentials of Project Management, copyright © 2021 by Adam Farag, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

"Chapter 13: Procurement Management" in Project Management, copyright © 2014 by Adrienne Watt, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Exhibits 9.1, 9.2, and 9.3 are taken from Figures 13.1, 13.2, and 13.3 from "Chapter 13: Procurement Management" in Project Management, copyright © 2014 by Adrienne Watt, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

The multiple choice questions in the Checkpoint boxes were created using the output from the Arizona State University Question Generator tool and are shared under the Creative Commons - CC0 1.0 Universal License.

Image descriptions and alt text for the exhibits were created using the Arizona State University Image Accessibility Creator and are shared under the Creative Commons - CC0 1.0 Universal License.

A legal agreement between the organization/project and an entity (person or company) to provide goods or services to the organization/project at an agreed-on price.

A contract where an organization agrees to pay the contractor for the cost of performing the service or providing the goods most often used when the scope of work or the costs for performing the work are not well known.

An agreement where one party pays another party for all material and labour costs on a project.

The time involved during an activity that can be postponed without delaying the overall project.