12 Sport Psychology

Lori Dithurbide, School of Health and Human Performance, Dalhousie University

Poppy DesClouds, School of Human Kinetics, University of Ottawa

Kylie McNeill, School of Human Kinetics, University of Ottawa

Natalie Durand-Bush, School of Human Kinetics, University of Ottawa

Christina DeRoo, School of Health and Human Performance, Dalhousie University

Sommer Christie, Faculty of Kinesiology, University of Calgary

Overview

Sport and exercise psychology is the scientific study and application of human behaviour in the sport and exercise contexts (Gill & Williams, 2008). Sport and exercise psychology is often studied with one of two objectives in mind: 1) to understand the psychological impact on human performance and 2) to understand how sport and exercise participation impacts an individual’s psychological development and health (Weinberg & Gould, 2015). Exploring psychology from this framework has allowed for many significant discoveries including the development of theories and models which aim to account for the effects of variables including stress and exercise on outcomes including health and performance.

There are many careers related to sport and exercise psychology. Perhaps the most common career identified by students is “sport psychologist.” In Canada, professionals working in the field of sport and exercise psychology providing direct services to athletes and teams work under the title of Mental Performance Consultant (MPC). Although overlapping in some regards, MPCs and clinical psychologists have different scopes of professional practice.

This chapter will provide a brief overview of common methods and significant findings in foundational aspects of sport and exercise psychology. It will also explore more recent developments within the field of sport and exercise psychology, as well career paths, scopes of practice, and educational training paths for professionals working in this field.

Introduction to Sport and Exercise Psychology

Sport and exercise psychology is a relatively young scholarly discipline in comparison to other areas of study in psychology: it has its beginnings in the latter part of the 19th century when Norman Triplett (1898) wanted to understand why athletes sometimes performed better in groups than when alone (Weinberg & Gould, 2015). Since that time, the field has grown tremendously. For the purpose of this chapter, we will focus primarily on the ‘sport’ aspect of psychology while acknowledging that the ‘exercise’ aspect is highly related but can also be considered a separate field of study. There are now evidence-based graduate programs throughout Canada, the United States of America, and across the globe. There are also multiple national and international societies and organizations supporting the research and practice of sport and exercise psychology (e.g., Canadian Society for Psychomotor Learning and Sport Psychology; International Society of Sport Psychology) as well as national and international applied certification bodies either established or in development (e.g., Canadian Sport Psychology Association; Association of Applied Sport Psychology). Such growth in research and practice demonstrates that there is demand for knowledge and service in these areas of expertise.

Particularly in the context of sport performance, increased media attention along with the recognition and acceptance of sport psychology as a performance-enhancing tool has led to increased numbers of athletes, coaches, and sport organizations seeking out MPCs for their expertise and services. For example, MPCs are now commonly found practicing in sports such as golf. More recently, sport psychology has become integrated into sports including American football. For example, the Seattle Seahawks of the National Football League (NFL) have employed Dr. Michael Gervais, a clinical psychologist known for his work in sport and performance psychology. Indeed, he was a part of their team staff during their Super Bowl winning season of 2013.

Demand for the integration of sport psychology into the sport environment is evident as professional development opportunities are now often included in both coach and support staff training. For example, the Canada’s National Coaching Certification Program (NCCP) includes modules on sport and performance psychology. Sport medical professionals including athletic therapists, sport medical physicians, nutritionists, physiotherapists, and sport chiropractors can also often take sport psychology courses as requirements or electives during their training. Both MPCs and related sports professionals serve an integral part of integrated support teams (ISTs) in the Canadian amateur sport system. ISTs include coaches, MPCs, strength and conditioning specialists, nutritionists, and medical staff, among other experts whose purpose is to help support and provide resources for athletes and coaches. An MPC can also have a unique role within the IST. Like the other professionals, they support the athletes and coaches through education and skill development (mental skills in this case). However, their training also enables them to assist and provide expertise in the functioning of the IST itself, helping bring professionals from differing disciplines together by enhancing communication and team dynamics. Additionally, they can support other professionals in their work by providing guidance on topics such as the psychology of injury rehabilitation, and coach-athlete management.

In recent years, increased conversations and visibility surrounding mental health and athletes has increased awareness of the field of sport and exercise psychology in areas that go beyond sport performance. Importantly, research has examined the link between sport and exercise participation and their relationship to mental health, and the impact of physical activity on the prevention and treatment of mental health challenges and conditions (see Schinke, Stambulova, Si, & Moore, 2017). In addition to research, well-recognized and successful athletes such as Clara Hughes, Michael Phelps, and DeMar DeRozen have openly discussed their challenges with mental health. This has created an opportunity for athletes to express and discuss their own mental health experiences. Although clinical mental health issues are often beyond the scope of practice amongst most MPCs (detailed in the section titled Applications of Sport and Exercise Psychology below), it remains an important topic of research, discussion, and practice for those interested in the field of sport and exercise psychology. Demonstrating the importance of sport and mental health, the Canadian Centre for Mental Health and Sport, a not-for-profit organization was developed to support the mental health and performance of competitive and high-performing athletes and coaches in Canada (https://www.ccmhs-ccsms.ca/).

Significant Research Findings

Although there is a myth that sport psychology is only applicable to elite sport performers, research and applications from this field have far-reaching impact. For example, there is significant recent research exploring the psychological impact of early specialization in youth sport. Research demonstrates that young children will not benefit from early sport specialization in the majority of sports, and may have a greater risk of overuse injury and burnout from concentrated participation (e.g. LaPrade, et al., 2016). Research in sport and exercise psychology has also demonstrated positive benefits of sport and physical activity participation in adults. For example, military veterans with a disability have shown to have a greater sense of independence and choice when engaging in quality physical activity experiences (Shirazipour et al., 2017). Perhaps gaining more mainstream attention, research has importantly demonstrated that sport-related concussions may be associated with increased risk of mood disturbances and depression (Covassin, Elbin, Beidler, LaFevor, & Kontos, 2017). Consequently, it is important to recognize that the study of sport psychology is relevant to many contexts and setting beyond the competitive field of play.

Further demonstrating the widespread applicability of sport and exercise psychology, there is a substantial body of evidence to support the notion that physical activity (including sport participation) can both help prevent and treat some forms of mental health challenges and illness. For example, a systematic review conducted by Mammen and Faulkner (2013) found a significant, inverse relationship between physical activity at baseline and depression at follow-up in 25 of 30 longitudinal studies. Furthermore, their results suggested that any level of physical activity might help prevent depression. Moreover, an earlier and well-cited longitudinal study by Camacho, Roberts, Lazarus, Kaplan, and Cohen (1991) found a relationship between inactivity and the incidence of depression over the course of almost 20 years.

Recently, more attention has been focused on the impact of physical activity, including sport participation, on the treatment of mental health challenges such as depression and anxiety. Rebar and colleagues (2013) conducted a meta-meta-analysis examining the effect of physical activity on depression and anxiety in a non-clinical population. They found that across eight meta-analyses, physical activity had a moderate effect on the treatment of depression such that physical activity reduced depression, and a small effect on the treatment of anxiety such that physical activity reduced anxiety. Using a clinical population, Rosenbaum and colleagues (Rosenbaum, Tiedemann, Sherrington, Curtis, & Ward, 2014) conducted a systematic review of studies using physical activity interventions. They found that physical activity reduced symptoms of depression in people with mental illness, and also found a reduction of symptoms associated with schizophrenia and improvements in other physical health markers in people diagnosed with schizophrenia.

More recently, White and colleagues (2017) examined the impact of domain-specific physical activity on mental health. That is, does the context in which one performs a physical activity (e.g., leisure versus work-related physical activity) have an impact on one’s mental health. Using a meta-analytic approach, they found that leisure-time physical activity and transport physical activity both had a positive relationship with mental health. They also found that leisure-time physical activity and participation in school sport had an inverse relationship with mental ill-health (the greater the participation, the lower levels of ill-health). However, work-related physical activity had a positive relationship with mental ill-health: if an individual’s main sources of physical activity was performed at the work place, it may have a negative impact on one’s mental health.

In the following sections, common frameworks and approaches to research in sport and exercise psychology are reviewed.

Common Frameworks for Research in Sport Psychology

Weinberg and Gould (2015) state that the ultimate goal of psychological skills training is self-regulation. They define self-regulation as the ability to work toward your goals by monitoring and managing your thoughts, feeling, and behaviours. They also describe psychological skills training as the systematic and consistent practice of mental skills for the purpose of enhancing performance, increasing pleasure and satisfaction in sport participation (Weinberg & Gould, 2015, p. 248), thus leading to greater abilities in self-regulation. The field of sport psychology has examined and shown support for a number of basic psychological skills to enhance performance and overall satisfaction. The following section briefly describes these skills, and some significant findings that support the implementation of these skills.

Goal setting

Goal setting is one of the most commonly used strategies across the behavioural sciences (Bar-Eli, Tenenbaum, Pie, Btesh, & Almog, 2007). Goal setting is commonly used to improve motivation, focus, and thus performance. Generally, goal setting in sport typically involves helping athletes to identify and set defined goals (i.e., outcome, performance, and process goals), and to identify and set goals for varying contexts (i.e., practice and competition goals) appropriate to the athlete’s performance expectations. Effective goal setting involves setting both long term (e.g., this year) and short term (e.g., today or this week) goals, and also includes goal setting evaluation (e.g., did I achieve my goals?).

Overall, goal setting has shown to be an effective technique for increasing the likelihood of achieving one’s goal (Kyllo & Landers, 1995). Research examining the relationship between various types of goals and performance across a variety of contexts generally indicates that goals associated with moderate to high levels of difficulty are linked to better performances (see Weinberg, 2000, 2004 for reviews). Goal setting also seems to be most effective on simple tasks rather than those that are very complex (Burton, 1989).

Stress/arousal management

A significant amount of research in sport psychology has theorized about and examined the impact of arousal on sport performance. Arousal is the combination of physiological and psychological activation that ranges from deep sleep to intense excitement (Weinberg & Gould, 2015). A variety of theories and models attempt to account for the impact of specific physiological and cognitive states/traits on performance. Such states and traits include stress, anxiety, and excitement. For the purpose and scope of this chapter, we will refer to one’s level of arousal or activation.

Many theories and models have been developed to explain the relationship between arousal and performance, and to discuss them all in sufficient detail for accuracy would be beyond the scope of this chapter. Instead, to provide broad conceptual overview, we discuss those theories and models that have received significant attention in the field, and we will focus on the broad concept of arousal/activation rather than the specific state(s) or trait(s).

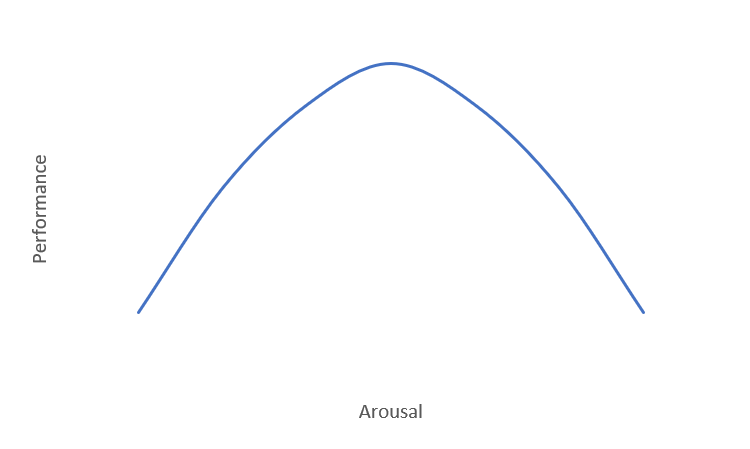

One of the first theories proposed to account for the relationship between arousal and performance was drive theory (Spence & Spence, 1966). This theory describes the relationship between arousal and performance in a positive linear fashion where a greater level of arousal leads to a greater level of performance. Although drive theory may be suitable for some tasks (e.g., power lifting), most sport psychology researchers were dissatisfied with its ability to predict most performances across a variety of tasks. The field thus turned to the inverted-U hypothesis that posits that both low and high levels of arousal elicit poor performances, and a moderate level of arousal results in optimal performance levels (Landers & Arent, 2010).

Although a more inclusive model, the inverted-U hypothesis lacks the ability to account for individual differences, and differences across sport or tasks. That is, moderate levels of arousal may be optimal for hockey, but perhaps not for archery or sprinting. This challenge of accounting for individual and situational variations lead to Hanin’s (1997) model of individualized zones of optimal functioning (IZOF). Simply stated, this model posits that each individual has their own zone of optimal functioning where anxiety levels can vary from one individual to another. Outside of this zone, athletes perform poorly. Hanin’s IZOF model was unique in that an athlete’s ‘zone’ did not have to be at a moderate level of arousal for optimal performance to occur. For example, Athlete 1’s optimal zone could be at a high level of arousal, where Athlete 2 would be a low-moderate level of arousal. Hanin also suggested that the optimal arousal level was not simply a point on a scale, but more of a zone or bandwidth. This model has been supported in the research with regards to its relationship with performance. However, it is criticized for having a lack of theoretical support. That is, answering why the IZOF model is supported (Gould & Tuffey, 1996).

Through understanding how arousal impacts one’s performance, MPCs can educate and support athletes in managing arousal and stress levels so that the athletes can achieve optimal performance in a variety of circumstances. In order to achieve this, MPCs first assist the athlete to become aware of their levels of arousal and activation during training and performance (Weinberg & Gould, 2015). MPCs have a number of techniques to assist with arousal management. These techniques are often categorized into either physiological arousal or anxiety reduction techniques, and cognitive arousal or anxiety reduction techniques. Physiological techniques for arousal and stress management include, but are not limited to, breath control, progressive muscles relaxation, and biofeedback. Cognitive techniques for arousal and stress management include, but are not limited to, relaxation response and desensitization (Weinberg & Gould, 2015). There can be some overlap in the techniques whereby engaging in physiological techniques may also impact one’s level of cognitive arousal. For example, when an individual engages in breathing exercise aimed at managing physiological arousal, it can also have a positive impact on an individual’s cognitive arousal.

Research conclusively supports that arousal and stress management can result in better performance. In particular, Rumbold, Fletcher, and Daniels (2012) conducted a review of 64 intervention studies where the goal was to reduce stress and increase performance. They found that 81% of the studies showed improvement in stress management, and 77% of the studies found improvements in performance. It also seemed that multimodal approaches (using more than just one strategy) were more effective than single modalities.

Imagery

In our work as MPCs, we often hear from athletes that imagery, also referred to as visualization, is a tool they often use. As a spectator, you may have observed athletes engaged in imagery, or you, yourself, may use imagery as a tool for enhancing performance (or using day dreaming as a distraction!). The premise of imagery is the creation of an image in our minds, either by recalling actual events, or by constructing our own images of events we hope, or want to avoid, happening. The term imagery is often preferred to visualization as it is not restricted to simply one sense, as would suggest the term visualization. Imagery can include, in addition to vision, one’s auditory sense (the sounds of the crowd), one’s sense of smell (the smell of chlorine at the swimming pool), one’s sense of touch (the feel of the ball in your hands), one’s kinaesthetic sense (the feeling of one’s limbs while executing a dive from the platform), and even one’s sense of taste (the salty taste of sweat while running long distances). Imagery is also a tool that can be used to rehearse performances mentally, whether the goal is learning a new routine (learning a new gymnastics floor routine), or helping to manage emotions in a high-pressure situation (imaging a large crowd at the championship game).

Research examining the effectiveness of imagery can be complex, particularly because it is not possible to actually see what the athlete is imaging. However, some case studies have shown that the use of imagery enhances performance and other psychological variables such as confidence and the ability to cope with anxiety (Evans, Jones, & Mullen, 2004; Post, Muncie, & Simpson, 2012).

Confidence

Research has indicated that confidence is the most consistent factor for differentiating between the most and least successful athletes (Jones & Hardy, 1990). In sport psychology, self-confidence is defined as the belief that you can successfully perform a behaviour (Weinberg & Gould, 2015). Vealey and Chase (2008) further describe sport self-confidence as a social cognitive construct. They differentiate between state self-confidence (e.g., how confident you feel today, before a particular competition) and trait self-confidence (e.g., how you generally feel in the day-to-day), and suggest that sport self-confidence can be viewed more as a trait than a state, depending on the context. Closely related to sport confidence as defined by Vealey and Chase (2008) is the concept of self-efficacy. Bandura (1997) defines self-efficacy as the perception of an individual’s ability to successfully perform a task. Thus, one could consider self-efficacy to be situation specific self-confidence. For the purpose and scope of this chapter, we will combine these constructs in discussing relevant research.

Confidence has been shown to impact other sport-related psychological factors. For example, confidence can impact how an athlete interprets their level of anxiety. Specifically, when an athlete is high in confidence, they are more likely to interpret anxiety as facilitative, as compared to when an athlete is low in confidence (Jones & Swain, 1995). Confidence has also been shown to influence perceptions of effort: athletes high in confidence, when compared to athletes low in confidence, tend to perceive that they expend less effort on a particular task (Hutchinson, Sherman, Martinovic, & Tenenbaum, 2008). Most importantly, confidence has also been shown to influence performance: athletes higher in confidence tend to perform better than those lower in confidence (Feltz, 1984; Moritz, Feltz, Fahrbach, & Mack, 2000). Because confidence can be considered as more of a psychological trait or a modifiable state depending on the context (as opposed to a skill), MPCs will often use tools such as goal setting and imagery in training over time to enhance self-confidence, and thus impact performance.

Focus

The ability to focus—to ignore distractions, and pay attention to relevant cues at the correct time, is one of the most important skills an athlete can possess. Perhaps even as a student, you have had difficulty focusing on the task at hand while being distracted by your electronic devices, the environment around you, or even your own thoughts. In sport psychology, we use the terms focus, concentration, attention, and managing distractions interchangeably as they all refer to the same skill of being able to direct our attention to the appropriate cue at the appropriate time.

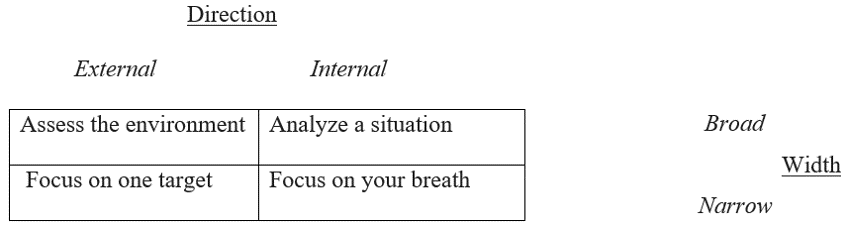

Individuals may often report that they have trouble paying attention, or concentrating. However, the reality is that we are always paying attention to something. If we find ourselves distracted or having difficulty focusing, it usually means we are not focusing on the appropriate cues. Nideffer (1976) and colleagues (Nideffer & Segal, 2001) described attentional focus along two dimensions: width (i.e., broad or narrow) and direction (i.e., external or internal). A broad attentional focus would be beneficial when an athlete has to be aware of and react to many changing cues in his or her environment. A narrow attentional focus would be helpful when an athlete must only focus on one or two cues, such as a target or finish line. An external focus of attention refers to attention focused on an external cue such as an object in the environment. Lastly, an internal focus of attention refers to attention focused inwardly such as one’s own thoughts and feelings.

To assess an individual’s attentional style (i.e., a person’s typical attentional disposition), Nideffer (1976) developed the Test of Attentional and Interpersonal Style (TAIS). Some research has supported the idea that focused attention is most beneficial when it is directed externally as compared to internally. Indeed, Wulf’s (2013) review found that an external focus of attention was more beneficial across a number of tasks including speed, endurance, and accuracy types of tasks than an internal focus of attention. Ways to train and improve concentration skills include using simulations, pre-determined cues, establishing good habits, routines, and competition plans, and overlearning skills (Weinberg & Gould, 2015).

Team Dynamics

A significant number of sports are not played alone – athletes often compete as a member of a team. Even in individual sports such as athletics, athletes may compete as an individual but are members of a larger team all competing for points, in addition to individual medals. The study of groups, or teams, has been a popular area of research in sport psychology just as it has been in related fields such as organizational psychology and social psychology. These disciplines indeed share many theories and models in their study of group performance.

There are a variety of approaches to group dynamic research in sport, but areas that have received significant attention, both in research and practice, are cohesion and collective efficacy. Cohesion in sport has been defined as a dynamic process in which a team has a tendency to stick together and stay united in pursuit of its goal and/or for the satisfaction of its members (Carron & Eys, 2012). Widmeyer, Brawley, and Carron (1985) developed the Group Environment Questionnaire to measure cohesion in sport and in doing so conceptualized group cohesion into two major categories: group integration (i.e., perception of the group as a unit) and individual attraction to the group (i.e., a member’s personal attraction to the group or team). Further, each of these categories can then be divided into either task or social aspects leading to a four-factor model of group cohesion. A meta-analytic review including 46 studies examining the relationship between group cohesion and performance in sport found a moderate to large effect size such that increased group cohesion is associated with increased performance outcomes (Carron, Colman, Wheeler, & Stevens, 2002).

Collective efficacy is a “group’s shared belief in its conjoint capability to organize and execute the courses of action required to produce given levels of attainment” (Bandura, 1997, p.477). Essentially, collective efficacy reflects a team’s level of confidence. Research has demonstrated that collective efficacy has a positive impact on team performance and that prior team performance can also have an impact on collective efficacy (Feltz & Lirgg, 1998; Myers, Feltz, & Short, 2004; Myers, Payment, Feltz, 2004).

Contemporary Methods and Developments

Mindfulness

Have you ever noticed yourself getting distracted during a task and then felt feelings of upset like anger, guilt, or frustration because you got distracted? This type of experience is a common one. While thoughts and events can distract a person from their point of focus (studying, communicating, performing a known skill), the evaluations or judgements that follow the distraction can become even more distracting. Researchers have theorized that these evaluations and judgements can lead to lowered performance in sport because of a focus on task-irrelevant thoughts (Gardner & Moore, 2004; Kaufman, Glass & Arnkoff, 2009). They highlight the importance of bringing the focus of attention back to what is most important now: your task.

The practice of mindfulness can help in moments of distraction, improving performance in daily tasks and athletic pursuits alike. Some may think of being mindful as simply having a calm demeanour in stressful situations, but it is much more than this. Being mindful involves being present with one’s circumstances intentionally and without judgment (Kabat-Zinn, 1994). Despite the simplicity of the mindfulness concept, its practice can be challenging. For those who do learn to be more mindful, the rewards can be numerous, including the potential to improve sleep and focus (MacDonald, Oprescu, & Kean, 2018), reduce stress (Lundqvist, Ståhl, Kenttä, & Thulin, 2018; Vidic, St. Martin, & Oxhandler, 2018), and improve performance (Zhang et al., 2016).

Originally popularized in North America by Jon Kabat-Zinn (1994), mindfulness is defined as “paying attention in a particular way: on purpose, in the present moment, and nonjudgmentally” (p. 4). This definition is based on Kabat-Zinn’s personal study of Buddhism, but he maintains that mindfulness based interventions need not promote or necessitate the practice of Buddhism, although some may find this helpful (Kabat-Zinn, 2017). Early research on the benefits of mindfulness began mostly outside of sport, looking at the use of a mindfulness practice alongside traditional medical treatments (Kabat-Zinn, 1982). An approach to facilitate mindfulness, known as Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction (MBSR), was developed with a primary goal to help relieve the suffering and stress of patients not fully responding to traditional medical treatment. A goal of MBSR was to create a model for other hospitals to implement with patients. The reach of MBSR has now gone beyond hospitals, and variations of MBSR have been incorporated into the areas of education, business, military, and sport (Kabat-Zinn, 2017). MBSR is an eight-week intervention that attempts to cultivate a greater ability to notice a patient’s inner and outer world (Kabat-Zinn, 1990; Santorelli, 1999). Sport-focused approaches to mindfulness have largely been adapted from this model.

Mindfulness as an approach to improving sport performance is a relatively recent development in the field of sport psychology compared to more traditional psychological skills interventions. While Kabat-Zinn, Beall and Rippe described the first known use of mindfulness with athletes in 1985, the 1990s showed little uptake in the use of mindfulness in sport. Beyond the early 2000s, however, research and use of mindfulness-based interventions in sport have grown substantially. Evidence now exists that supports a moderate improvement in sport performance for those athletes employing mindfulness techniques, and this is especially true in sport tasks based on precision (Bühlmayer, Birrer, Röthlin, Faude, & Donath, 2017).

Mindfulness to enhance performance and well-being has been taught to athletes through two main interventions: Mindfulness-Acceptance-Commitment therapy (MAC; Gardner & Moore, 2012) and Mindful Sport Performance Enhancement (MSPE; Kaufman, Glass & Arnkoff, 2009). Currently more robust evidence exists for the ability of MAC to improve performance, but research on MSPE is in its infancy.

Mindfulness-Acceptance-Commitment therapy (MAC)

The MAC intervention was developed by Gardner and Moore (2004) and is influenced by Kabat-Zinn’s definition of mindfulness (1994), combined with acceptance and commitment therapy approaches used in counselling psychology (Hayes, Strosahl, & Wilson, 1999). In MAC, mindful awareness is accompanied with acceptance of the current experience as it is, and commitment to value or goal driven behaviour (versus emotion-driven behaviour). The commitment component of the MAC approach requires a prior knowledge and understanding of the athlete’s values and goals, and of the behaviours that help their performance. Thus, self-awareness and knowledge of their sport is required in order to make full use of this approach in performance improvement.

In their rationale for the use of mindfulness to improve sport performance, Gardner and Moore (2004) acknowledged that although improvement can be detected in use of a mental skill (e.g., imagery, positive self-talk), most mental skills used in interventions with athletes show inconsistent results regarding performance improvement. They argued that this might be because of inaccurate assumptions regarding what leads to excellent performance. Traditional mental skills training focuses on control of internal states by managing thoughts, images and emotions (Gardner & Moore, 2004; Moore, 2009). Moore argues that these control-based techniques are built on the assumption that there is an “ideal state” that leads to excellent performance, and that an athlete must experience that ideal state in order to perform their best. Anecdotally, many athletes know this to be incorrect, at least some of the time, as many athletes can think of a time that they performed well while experiencing a host of negative emotions and sensations. Gardner and Moore (2012) argue that a mindful approach to sport performance is effective for maintaining or improving performance by increasing the proportion of thoughts or present-moment observations that are applicable to the task at hand.

There are seven modules in the MAC intervention that are completed in order, and a coach or leader must ensure athlete comprehension of each module before continuing (Gardner & Moore, 2007). Because of this focus on mastery of content, the length of the MAC intervention can vary, but it will last at least seven weeks.

Mindful Sport Performance Enhancement (MSPE)

In contrast to MAC, the MSPE approach focuses less on values and value-driven behaviour, and more on the progressive practice of non-reactive attentional control (Kaufman, Glass, & Pineau, 2018). MSPE uses the terms concentration, letting go, relaxation, harmony and rhythm, and forming key associations (finding personal cues that bring you back into the moment) to describe the focus of the approach. The progression of practice begins with quiet settings and watching the breath or scanning the body. Over the course of the intervention, athletes are encouraged to practice these skills at home and log their experiences for later discussion. An acronym used to integrate mindfulness into life outside of sport and the training sessions is STOP: stop, take a few breaths, observe, and proceed (Kaufman et al., 2018).

Mindfulness in sport takes a different approach to performance improvement when compared to traditional mental skills training. That being said, it can be used in conjunction with traditional mental skills as described earlier in this chapter. There is evidence of improvement in athlete performance, mental health and well-being through the application of positive self-talk, imagery, goal setting, relaxation or activation. As with any mental, physical or social skill, proper and consistent practice is key to improvement and ease of use.

Neurofeedback and Biofeedback Training for Optimizing Sport Performance

Psychophysiology is defined as “the scientific study of the interrelationships of physiological and cognitive processes” (Schwartz & Olson, 2003, p. 5) and two types of psychophysiological interventions utilized in sport include neurofeedback training (NFT) and biofeedback training (BFT). The training process involves the measurement of physiological or neurological activity that is then fed back to the athlete in real time in the form of audio or visual cues that enable the athlete to develop greater self-awareness and ability to voluntarily regulate physiological and neurological processes (Blumenstein & Hung, 2016; Schwartz & Andrasik, 2017).

Biofeedback training (BFT)

BFT equipment measures and feeds back physiological information associated with the stress response (e.g., heart rate, respiration rate and depth, heart rate variability, peripheral body temperature, and electrodermal activity) and has been identified as “one of the most powerful techniques for facilitating learning of arousal-regulation” (Bar-Eli, Dreshman, Blumenstein, & Weinstein, 2002, p. 568). Fundamentally, when the sympathetic nervous system is activated, the body responds physiologically by increasing respiration rate, heart rate, electrodermal activity, and muscle tension, and by decreasing peripheral body temperature, in order to prepare the body to ‘fight or flee’ the stressful situation (e.g., Filaire, Alix, Ferrand, & Verger, 2009). During BFT athletes observe their physiological data on the computer screen and train the ability to actively alter the various responses. For example, if under stress an athlete may tense his or her muscles, he or she would be encouraged to observe the tension level and attempt to lower it.

Neurofeedback training (NFT)

NFT also known as electroencephalography (EEG) biofeedback, involves the measurement of cortical activity (Schwartz & Andrasik, 2017). During NFT, electrodes are placed at specific locations on the surface of the scalp and measure minute electrical signals, which appear in five major frequencies: delta, theta, alpha, beta, and gamma (Cacioppo, Tassinary, & Berntson, 2016). For a comprehensive review on the relationship between cortical frequency and sport see Cheron et al. (2016). During NFT, relevant components of the athlete’s EEG are extracted and fed back in the form of audio and/or visual cues that indicate when they have met the predetermined threshold (Vernon, 2005). This feedback loop (generally considered operant conditioning) allows athletes to see their brainwaves visually, and based on reward contingent feedback, gives them the ability to progressively alter their brainwaves (Hammond, 2011; Schwartz & Andrasik, 2017). For example, sensorimotor rhythm (SMR) – a specific frequency within the low beta range that is correlated with alert but calm mental state (Thompson & Thompson, 2015) – has been shown to enhance golf putting performance in golfers (Cheng et al., 2015).

In sum, BFT/NFT helps athletes to learn how to effectively self-regulate physiological arousal and focus in the competitive environment. BFT and NFT have been shown to reduce anxiety (Gevirtz, 2007), improve attention (Gruzelier, Egner, & Vernon, 2006), develop self-efficacy (Davis & Sime, 2005), and ultimately enhance performance (e.g., Blumenstein & Hung, 2016; Mirifar, Beckmann, & Ehrlenspiel, 2017; Morgan & Mora, 2017; Xiang, Hou, Liao, Liao, & Hu, 2018)

Applications of Sport and Exercise Psychology

Sport psychology is a relatively new and rapidly expanding field. As a result, several graduate training pathways and career options have become available to those wishing to work in this area. There have traditionally been two streams within the discipline of sport psychology: research and professional practice. Although each is associated with different training paths (Fitzpatrick, Monda, & Butters Wooding, 2016), there is considerable crossover between research and professional practice, as both undeniably inform one another. This has unsurprisingly led to calls for more interdisciplinary training (see Careers section below; Wylleman, Harwood, Elbe, Reints, & De Caluwé, 2009). This section of the chapter will address both research and professional practice streams, and highlight career and graduate training opportunities available in Canada.

The Profession of Sport Psychology in Canada

To provide some context, it is valuable to first situate the profession of sport psychology in Canada. From a professional practice standpoint, sport psychology and more specifically, mental performance consulting, is overseen by the Canadian Sport Psychology Association (CSPA). The CSPA was developed in 2006 by Drs. Natalie Durand-Bush, Penny Werthner, and Tom Patrick, based on the initial Canadian Mental Training Registry (CMTR) established by Dr. Terry Orlick. The CSPA specifies education and training requirements to provide mental performance consulting services in Canada, and recognizes professionals who possess minimum competencies to work in this field. Notably, individuals must have (a) a Master’s degree in sport psychology or related field, (b) demonstrated understanding of foundational disciplines such as human kinetics/kinesiology, psychology, and counselling, (c) extensive consulting experience and hands-on experience in sport, and (d) favourable supervisor and client evaluations (CSPA, 2018; https://www.cspa-acps.com/about).

The CSPA offers professional, student, and academic membership, and provides mentoring and supervision opportunities for students and young professionals aspiring to become professional members. It is noteworthy that within its professional membership, the CSPA distinguishes between mental performance consultants and registered psychologists. According to the CSPA (2018, p. 2):

Mental Performance Consultants (MPCs) are extensively trained in the area of sport sciences and have acquired fundamental knowledge in psychology and counselling through university undergraduate and graduate coursework. MPCs provide individual or group consultations geared towards improving sport performance and well-being related issues. They do not diagnose or treat mental health issues. Psychologists working in the area of sport are extensively trained in clinical or counselling psychology and have acquired fundamental sport science knowledge through university undergraduate and graduate coursework. They provide individual or group consultations geared towards improving sport performance and diagnose and treat a range of mental health issues such as addictions, eating disorders, depression, and anxiety.

All in all, the CSPA is an important reference for those interested in pursuing a career and completing requisite training in the field of sport psychology in Canada. The Canadian Psychological Association also provides information for psychologists wishing to add sport and exercise as an area of practice (Canadian Psychological Association, 2018), however this information is limited.

Sport Psychology Careers and Training Pathways in Canada

In order to provide a comprehensive description of career and graduate training opportunities to work in the field of sport psychology in Canada, the profiles of current professional members of the CSPA were examined to identify their credentials, educational and training background, and professional roles and affiliations. This data also served to identify alternative career paths outside of traditional professional practice and research. Furthermore, building from Durand-Bush and McNeill’s (2016) chapter on the history of sport psychology in Canada, graduate training programs within Canada’s 97 publicly funded universities (Universities Canada, 2018) were also examined to locate any new education and training opportunities for students pursuing graduate studies in this field. These programs were limited to those in which students can specialize in sport psychology within a kinesiology, human kinetics, or physical activity/education department. Finally, literature related to sport psychology career paths and graduate training in Canada was reviewed. Given the lack of information specific to the Canadian context, literature targeting the United States and Europe was considered.

Career Pathways

Careers in sport psychology typically involve two streams: research and/or professional practice (i.e., mental performance consulting). While some professionals train and work exclusively in one stream, many pursue both. For instance, a review of the public profiles of CSPA professional members illustrates that several of them perform both scholarly and applied work, and actively engage in this dual role. This reinforces the research-practice orientation of the field of sport psychology in Canada (Schinke & McGannon, 2014).

Research-focused careers

In terms of research-focused careers, a prominent option for those who have completed a doctoral degree in sport psychology is an academic position in a post-secondary institution (e.g., Assistant Professor) in Canada or abroad (Fitzpatrick et al., 2016). Such positions can be held in research-intensive universities where there is an expectation for scholarship and supervision of undergraduate and graduate students, or in teaching-intensive universities where teaching and student mentorship are prioritized. A typical academic position in a research-intensive university in Canada involves teaching (e.g., lecturing, supervising students), research (e.g., securing grants, preparing peer-reviewed publications), and service (e.g., serving on committees, performing administrative tasks; Gravestock & Gregor Greenleaf, 2008). Generally, work expectation of a tenure-track professor in most Ontario universities is, “40% time/effort allocation to teaching, 40% to research, and 20% to service” (Jonker & Hicks, 2014, p. 7).

There are also research-oriented careers outside of academia. Such positions can be found within the sport domain to conduct research and program evaluation for organizations such as the Coaching Association of Canada and the Canadian Olympic Committee. Outside of sport, positions have been offered within the government (e.g., Department of National Defense) and healthcare (e.g., Canadian Medical Association) sector to investigate, for example, resilience and well-being in military personnel and physicians.

Careers in professional practice

There are two types of careers related to professional practice in sport and exercise psychology, depending on practitioners’ education and training. As highlighted by the CSPA, practitioners can work as an MPC or a licensed mental health professional (e.g., registered psychologist, certified psychotherapist, or counsellor) in the context of sport. It is important to note that in Canada, there is no official title of “sport psychologist” either with the Canadian Psychological Association or the CSPA. The correct title for those who are licensed to work as a psychologist in their respective province or territory is registered psychologist (R. Psych.; Wall, 2016). Both types of practitioners can become professional members of the CSPA and/or AASP (Association of Applied Sport Psychology—a comparable organization to CSPA in the USA). Specific course work and supervised practice is a requirement no matter the educational background of the professional (see Training section, below). Moreover, as the CSPA and AASP plan to unify their procedures and certification standards within coming years, it is likely that Canadian and American practitioners will be able to follow similar certification procedures and adopt the credential of “Certified Mental Performance Consultant” or “CMPC ®” (Association for Applied Sport Psychology, 2018; Schinke et al., 2018).

The MPC role is that which most students have in mind when working towards professional practice in the field of sport psychology. The goals of a MPC are to teach, guide, and support individuals in their practice and development of psychosocial skills for optimal performance, day-to-day living, and well-being. In order to clearly define the role of sport psychology practitioners, AASP conducted a Job Task Analysis and identified:

[Six] 6 domains of practice (e.g., Goals, Outcome, and Planning), 21 tasks/discrete work activities (e.g., identify personal and systematic resources and barriers related to the achievement of goals and desired outcomes), and 38 underlying knowledge statements (e.g., intervention research and its application) related to the competent and effective practice of certification-level professionals in sport psychology” (AASP Interim Certification Council, 2017).

In particular, effective MPCs work in an interdisciplinary fashion and can provide services to a range of performers in diverse contexts in order to address specific sport/performance issues as well as more general well-being affecting daily functioning in life.

Those pursuing careers as registered psychologists, counsellors, or psychotherapists may choose to apply their work specifically in the context of sport and complete additional training in sport sciences to fully understand and navigate the competitive sport environment. They may also seek the designation of MPC within the CPSA, provided they meet the registration criteria (see Training section below). While these practitioners may consult on sport performance concerns, they can also focus on diagnosis and treatment of clinical symptoms and mental disorders such as addictions, eating disorders, and depression. Although there are distinctions between the career paths of MPCs and registered psychologists, the need for collaboration between these two types of practitioners has been emphasized by the CSPA and CPA (Canadian Psychological Association, 2018) in order to more comprehensively tend to the needs of athletes. The new Canadian Centre for Mental Health and Sport (CCMHS, 2018) has as its mandate to provide interdisciplinary services for competitive and high-performance athletes and coaches experiencing mental health challenges and mental illness. The collaborative sport-specialized mental health care team indeed includes MPCs, registered psychologists, psychotherapists, counsellors, and psychiatrists. Having all of these important practitioners working in unison to determine athletes and coaches’ needs and mental health care plans while respecting their performance goals and sport culture will arguably lead to better experiences and outcomes.

A career as a sport psychology practitioner (e.g., MPC, MPC-CCC, MPC-R. Psych.) is dynamic and multifaceted. Given the developing nature of the field of sport psychology, many professionals take on a mixture of full- and part-time contracts with sport organizations, teams, and individual clients, as well as multi-roles that combine administrative duties with mental performance consulting. Practitioners endeavouring to develop and sustain a private practice can benefit from additional know-how in business management, finance, and marketing. Unfortunately, these are topics that still require attention in most graduate training programs (Wylleman et al., 2009).

Practitioners also work in various related, but non-sport-specific fields to provide mental performance consulting in domains such as healthcare, education, and the workplace. Some adopt multiple roles by combining academic and leadership/management positions with their own sport psychology practice. For example, individuals have concurrently worked as an MPC, registered counsellor, adjunct professor, and sport centre director.

Other career options for those who have studied sport psychology include sport-related roles (e.g., High Performance Advisors) within organizations such as Own the Podium and the Canadian Paralympic Committee. Moreover, training in this field is highly relevant for intervention, consultation, and program development in professions pertaining to health, education, and high-risk management (e.g., military, fire fighter, police, paramedic). Examples of such careers include (a) counselling within Canadian university student services centers to support students’ academic success, (b) providing mental performance services within the Canadian Special Operations Forces Command to enhance the morale, welfare, and operational readiness of military personnel, and (c) providing resilience training in hospitals to help children and families cope with cancer.

Educational Paths and Training

Although research and professional practice career paths in sport psychology intersect, the training requirements to successfully pursue these careers tend to be more distinctly delineated. One study showed that graduate students in this area often feel that they cannot gain the “best of both worlds” by completing a single educational program and thus have to make an explicit choice between pursuing an academic research position and professional practice (Fitzpatrick et al., 2016). As such, those who wish to combine both aspects in their work may need to seek additional training opportunities outside of their program requirements. That said, some graduate programs in Canada provide the opportunity for students to combine research training with applied consulting work and supervision, such as the Master of Human Kinetics (MHK) program offered at Laurentian University (i.e., includes an optional internship course as part of the thesis-based, research program).

Training for research

Research careers related to sport psychology, whether in post-secondary institutions or outside of academia (e.g., in the public sector) typically require graduate research training acquired in thesis-based Master’s (e.g., MA, MSc) and/or doctoral (i.e., PhD) degrees. For students who pursue non-thesis-based Master’s degrees (see Professional practice section below), additional coursework (e.g., in research methods) and research experience can prepare them for research careers. Faculty members in Canadian universities normally hold a doctoral degree in their field of study; however, given the competitive nature of the field, it is not uncommon to pursue post-doctoral training (e.g., a post-doctoral fellowship) to obtain an academic position. Those who conduct research outside of higher education (e.g., in industry or the public sector) often acquire the research competencies necessary for their roles by completing a Master’s degree, although a doctoral degree may be required for more senior research positions (e.g., Research Associates).

Canada has a history of vibrant scholarship in sport psychology, and over the past few decades, there has been a proliferation of high quality graduate programs in the field (Durand-Bush & McNeill, 2016). Therefore, many opportunities exist for students who wish to acquire research training in sport psychology. According to Durand-Bush and McNeill, approximately 25% of Canadian public universities offer graduate programs in which one can specialize in sport psychology. These programs are housed within sport science departments (i.e., kinesiology, human kinetics, physical activity/education) and offer students the possibility to study psychological aspects of sport with faculty members who conduct research in sport psychology. A graduate degree in psychology (e.g., experimental, clinical, counselling) with a research focus on sport is another pathway to an academic or research career in the field, however, coursework and training in sport psychology tends to be limited in psychology programs (Stewart, 2017).

Overall, as the discipline continues to grow, and as recent doctoral graduates enter faculty positions, so too do the research training opportunities for students in Canada. In addition to the 24 programs listed by Durand-Bush and McNeill (2016), students can also specialize in sport psychology research in graduate programs at Nipissing University (MSc, MEd, PhD), Lakehead University (MSc), Dalhousie University (MSc, PhD), University of Lethbridge (MA, MSc), and the University of Prince Edward Island (MSc). Given the diversification of the field of sport psychology and its interdisciplinary nature, research within graduate programs may focus on a variety of topics, depending on the interests of thesis supervisors. Examples include psychological skills training, life skill development, concussion management, injury rehabilitation, mental health and well-being, motivation and emotion, leadership and group dynamics, and physical activity promotion. These topics could be researched within different contexts in (e.g., youth, elite, disability sport) and outside of sport (e.g., business, performing arts, military, medicine).

While pursuing thesis-based graduate degrees, students can expect some coursework related to sport psychology, but given the interdisciplinary nature of these programs, they may also complete coursework within the broader field of sport sciences. Importantly, these programs involve completing a Master’s thesis or doctoral dissertation, in which students conduct novel research in order to make new contributions to the sport psychology literature. Master’s degrees generally require two years of full-time study, while doctoral degrees typically span four years or more. However, students are encouraged to consult the specific requirements of the programs in which they are interested and should take note of the additional research training that may be required to achieve their career goals.

Training for professional practice

In comparison to Canadian research-oriented sport psychology programs, graduate programs preparing students for professional practice are limited (Durand-Bush & McNeill, 2016). That said, some programs geared toward applied careers in the field do exist. Two programs offer students the opportunity to gain both applied experience and research skills in the field, without the requirement of a traditional Master’s thesis. The University of British Columbia offers a course-based (i.e., without a thesis) Master of Kinesiology degree. This one-year program provides training in different areas of study (i.e., Socio-Managerial, Natural/Physical Science, Behavioral Science, and Coaching Science), with the most popular being the Coaching Science stream (Durand-Bush & McNeill). Students are required to complete coursework, a research paper, and have the option to carry out an additional directed field study. Another unique course-based program is the Master of Human Kinetics in Applied Human Performance (Internship Option) at the University of Windsor. Over the course of 16 to 24 months, students complete coursework and a 360-hour Kinesiology internship, as well as a research project. This internship program option is meant to provide students with both field-work and research experience, and students are required to complete a research project in order to receive credit for their applied internship work.

For those wishing to pursue a career as a sport psychology practitioner, graduate training will depend on their desired scope of practice (e.g., MPC, Certified Counsellor, Registered Psychologist). Students should examine the professional membership requirements of the CSPA, CPA, and/or Canadian Counselling and Psychotherapy Association (CCPA) to help guide their training pathway. The general criteria for CSPA professional membership includes a Master’s degree in sport psychology (or a related field), coursework in sport psychology, sport sciences, counselling, and psychology, a 400-hour supervised internship, and favourable evaluations from supervisors and clients from sport and related settings. A review of CSPA professional membership profiles revealed that many members have extensive competitive sport experience as an athlete or coach (e.g., at varsity, national, and/or Olympic level) and/or as a sport professional (e.g., kinesiologists, athletic trainer). Competencies and experience in sport are requirements for professional membership with the CSPA (CSPA, 2018), as well as for certification with AASP in the USA (AASP, 2018).

Presently, the Master’s of Human Kinetics at the University of Ottawa is the only professional graduate program in Canada geared toward preparing students to meet CSPA professional membership requirements. In this four-semester, course-based Master’s program, students complete coursework in counselling, sport and exercise psychology theory, mental skills training and quality of life, professional ethics, and analysis and enhancement of consulting interventions. They may also complete courses in research methods, statistics, organizational behaviour, and sport law, as well as engage in a semester-based directed study if they desire research experience. Their coursework is complemented by an extensive 400-hour supervised internship in sport, physical activity, health, education, business, and/or performing arts contexts. Students who complete thesis-based graduate degrees in sport psychology can, nonetheless, achieve professional membership with CSPA by seeking out supervised practical experiences and additional coursework outside of their academic program.

Individuals who wish to work in the field of sport psychology as registered psychologists or related vocations such as registered counsellors or psychotherapists should refer to the specific requirements for licensure within their respective province or territory. It is important to note that formal opportunities to study sport psychology within clinical/counselling psychology departments is limited (Stewart, 2017). However, some professors who are professional members of the CSPA have academic appointments within psychology departments (e.g., Simon Fraser University, University of Regina, University of Manitoba). There are also professors conducting research in the field of sport psychology within programs that offer clinical psychology training in Canada (e.g., University of Ottawa, Université du Québec à Montréal). Thus, while these programs do not offer specialization in sport psychology, students could potentially pursue a doctoral degree in clinical psychology (e.g., PhD, PsyD) while conducting research on topics in sport psychology (e.g., motivation, coping, passion in sport).

Programs housed in psychology departments have coursework that is focused on psychology, and these programs tend not to have courses in sport science. Thus, in order to learn about the field of sport psychology, it is likely that students would need to seek out additional courses in sport sciences and sport psychology outside of their department (Wall, 2016). This is particularly important for those wishing to become professional members with CSPA or obtain CMPC© certification through AASP, as coursework in sport psychology and sport sciences is a requirement for professional membership. Additionally, students would need to find field placements that meet both clinical psychology and sport criteria in order to develop competencies specific to sport performance that satisfy CSPA or AASP requirements. Thus, while students who pursue graduate studies in psychology programs can go on to pursue careers in applied sport psychology, this trajectory involves completing additional coursework and clinical work related to sport outside of their department. This reinforces the notion that students from all training pathways need to take a self-directed approach to develop the necessary competencies to work as a professional sport psychology practitioner (Wall).

Concluding Remarks

In summary, there are several careers and training paths available to those wishing to specialize and work in the field of sport psychology in Canada. Both research and professional practice are meaningful endeavours to pursue and a combination of these two options is often an ideal choice for those seeking to play multiple roles. Canada is home to several diversified sport psychology graduate programs directed by world-leading scholars and practitioners. Students can therefore find an educational program that meets their personal needs and interests. They equally have the option to complete additional training to meet the requirements of research and/or professional practice organizations that will open doors for future employment.

References

AASP Interim Certification Council. (2017, August 23). CMPC credential and mark rationale. Retrieved from https://appliedsportpsych.org/certification/certification-program-updates/cmpc-credential-and-mark-rationale/

Association for Applied Sport Psychology (2018). Certification. Retrieved from https://appliedsportpsych.org/certification/

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York, NY: Freeman.

Bar-Eli, M., Dreshman, R., Blumenstein, B., & Weinstein, Y. (2002). The effect of mental training with biofeedback on the performance of young swimmers. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 51, 567–581. doi: 10.1111/1464-0597.00108

Bar-Eli, M., Tenenbaum, G., Pie, J. S., Btesh, Y., & Almog, A. (2007). Effect of goal difficulty, goal specificity, and duration of practice time intervals on muscular endurance performance. In D. Smith & M. Bar-Eli (Eds.), Essential readings in sport and exercise psychology (pp. 305-313). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

Blumenstein, B., & Hung, T. M. (2016). Biofeedback in sport. In R. J. Schinke, K. R. McGannon, & B. Smith (Eds.), Routledge international handbook of sport psychology (pp. 429–438). New York, NY: Routledge.

Bühlmayer, L., Birrer, D., Röthlin, P., Faude, O., & Donath, L. (2017). Effects of mindfulness practice on performance-relevant parameters and performance outcomes in sports: A meta-analytical review. Sports Medicine, 47(11), 2309-2321. doi: 10.1007/s40279-017-0752-9

Burton, D. (1989). The impact of goal specificity and task complexity on basketball skill development. The Sport Psychologist, 3, 34-47. doi:10.1123/tsp.3.1.34

CCMHS. (2018). About Us. Retrieved from https://www.ccmhs-ccsms.ca/

Cacioppo, J. T., Tassinary, L. G., & Berntson, G. G. (2016). Handbook of psychophysiology (4th ed.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Camacho, T. C., Robert, R. E., Lazarus, N. B., Kaplan, G. A., & Cohen, R. D. (1991). Physical activity and depression: Evidence from the Alameda county study. American Journal of Epidemiology, 134, 220-231.

Canadian Psychological Association. (2018). Sport and exercise section: Sport psychology training. Retrieved from https://cpa.ca/sections/sportandexercise/training/

Carron, A. V., Colman, M., Wheeler, J., & Stevens, D. (2002). Cohesion and performance in sport: A meta-analysis. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 24, 168-188. doi: 10.1123/jsep.24.2.168

Carron, A. V., & Eys, M. (2012). Group dynamics in sport (4th ed.). Morgantown, WV: Fitness Information Technology.

Cheng, M.-Y., Huang, C.-J., Chang, Y.-K., Koester, D., Schack, T., & Hung, T.-M. (2015). Sensorimotor rhythm neurofeedback enhances golf putting performance. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 37(6), 626–636. doi: 10.1123/jsep.2015-0166

Cheron, G., Petit, G., Cheron, J., Leroy, A., Cebolla, A., Cevallos, C., … Clarinval, A. M. (2016). Brain oscillations in sport: Toward EEG biomarkers of performance. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1–25. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00246

Covassin, T., Elbin, R. J., Beidler, E., LaFevor, M., & Kontos, A. P. (2017). A review of psychological issues that may be associated with a sport-related concussion in youth and collegiate athletes. Sport, Exercise, and Performance Psychology, 6(3), 220-229. doi:10.1037/spy0000105

CSPA. (2018). Resources. Retrieved from https://docs.wixstatic.com/ugd/2a9225_edc9a54674934f89896fd9445099fb2f.pdf

Davis, P. A., & Sime, W. E. (2005). Toward a psychophysiology of performance: Sport psychology principles dealing with anxiety. International Journal of Stress Management, 12, 363–378. doi: 10.1037/1072-5245.12.4.363

Davis, P., Sime, W. E., & Robertson, J. (2007). Sport psychophysiology and peak performance applications of stress management. In P. M. Lehrer, W. E. Sime, & R. L. Woolfolk (Eds.), Principles and Practice of Stress Management (3rd ed., pp. 615–637). New York: Guilford Press.

Durand-Bush, N., & McNeill, K. (2016). [Sport psychology in] Canada. In R. J. Schinke, K. R. McGannon, & B. Smith (Eds.), The Routledge international handbook of sport psychology (pp. 65-80). Oxfordshire, UK: Routledge.

Evans, L., Jones, L., & Mullen, R. (2004). An imagery intervention during the competitive season with an elite rugby union player. The Sport Psychologist, 18, 252-271. doi:10.1123/tsp.18.3.252

Feltz, D. L. (1984). Self-efficacy as a cognitive mediator of athletic performance. In W. F. Straub & J. M. Williams (Eds.), Cognitive sport psychology (pp. 191-198). Lansing, NY: Sport Science Associates.

Feltz, D. L., & Lirgg, C. D. (1998). Perceived team and player efficacy in hockey. Journal of Applied Psychology, 83, 557-564. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.83.4.557

Filaire, E., Alix, D., Ferrand, C., & Verger, M. (2009). Psychophysiological stress in tennis players during the first single match of a tournament. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 34, 150–157. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.08.022

Fitzpatrick, S. J., Monda, S. J., & Butters Wooding, C. (2016). Great expectations: Career planning and training experiences of graduate students in sport and exercise psychology. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 28, 14-27. doi: 10.1080/10413200.2015.1052891

Gardner, F. L., & Moore, Z. E. (2004). A mindfulness-acceptance-commitment-based approach to athletic performance enhancement: Theoretical considerations. Behavior Therapy, 35(4), 707-723. doi:10.1016/S0005-7894(04)80016-9

Gardner, F. L., & Moore, Z. E. (2007). The psychology of enhancing human performance: The mindfulness-acceptance-commitment (MAC) approach. New York: Springer Publishing.

Gardner, F. L., & Moore, Z. E. (2012). Mindfulness and acceptance models in sport psychology: A decade of basic and applied scientific advancements. Canadian Psychology, 53(4), 309-318. doi: 10.1037/a0030220

Gevirtz, R. N. (2007). Psychophysiological perspectives on stress-related and anxiety disorders. In P. M. Lehrer, R. L. Woolfolk, & W. E. Sime (Eds.), Principles and practice of stress management (3rd ed., pp. 209-226). New York: Guilford Press.

Gill, D., & Williams, L. (2008). Psychological dynamics of sport and exercise (3rd ed.). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

Gould, D., & Tuffey, S. (1996). Zones of optimal functioning research: A review and critique. Anxiety, Stress, and Coping, 9, 53-68. doi:10.1080/10615809608249392

Gravestock, P., & Gregor Greenleaf, E. (2008). Overview of tenure and promotion policies across Canada. Report prepared for Mount Royal College (now Mount Royal University). Retrieved from https://www2.viu.ca/integratedplanning/documents/OverviewofTPPoliciesinCanada.pdf

Gruzelier, J., Egner, T., & Vernon, D. (2006). Validating the efficacy of neurofeedback for optimising performance. In N. Christa, & K. Wofgang (Eds.), Progress in Brain Research (Vol. 159, pp. 421–431). Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier.

Hammond, D. C. (2011). What is neurofeedback: An update. Journal of Neurotherapy, 15, 305-336. doi:10.108010874208.2011.623090

Hanin, Y. L. (1997). Emotions and athletic performance: Individual zones of optimal functioning. European Yearbook of Sport Psychology, 1, 29-72.

Hatfield, B. D., & Hillman, C. H. (2001). The psychophysiology of sport: A mechanistic understanding of the psychology of superior performance. In R. N. Singer, H. A. Hausenblas, & C. M. Janelle (Eds.), Handbook of sport psychology (2nd ed., pp. 362-386). New York: John Wiley.

Hayes, S. C., Strosahl, K., & Wilson, K. G. (1999). Acceptance and commitment therapy: An experiential approach to behavior change. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Hutchinson, J., Sherman, T., Martinovic, N., & Tenenbaum, G. (2008). The effect of manipulated self-efficacy on perceived sustained effort. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 20, 457-472. doi:10.1080/10413200802351151

Jones, G. & Hardy, L. (1990). Stress in sport: Experiences of some elite performers. In G. Jones & L. Hardy (Eds.), Stress and performance in sport (pp. 247-277). Chichester, UK: Wiley.

Jones, G., & Swain, A. (1995). Predisposition to experience debilitative and facilitative anxiety in elite and non-elite performers. The Sport Psychologist, 9, 201-211. doi:10.1123/tsp.0.2.201

Jonker, L., & Hicks, M. (2014). Teaching loads and research outputs of Ontario university faculty members: Implications for productivity and differentiation. Toronto, ON: Higher Education Quality Council of Ontario.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (1982). An outpatient program in behavioral medicine for chronic pain patients based on the practice of mindfulness meditation: Theoretical considerations and preliminary results. General Hospital Psychiatry, 4, 33-47. doi: 10.1016/0163-8343(82)90026-3

Kabat-Zinn, J. (1990). Full catastrophe living: Using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain, and illness. New York, NY: Delacorte.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (1994). Wherever you go, there you are: Mindfulness meditation in everyday life. New York, NY: Hyperion.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (2017). Too early to tell: The potential impact and challenges—ethical and otherwise—inherent in the mainstreaming of dharma in an increasingly dystopian world. Mindfulness, 8, 1125-1135. doi: 10.1007/s12671-017-0758-2

Kaufman, K. A., Glass, C. R., & Arnkoff, D. B. (2009). Evaluation of mindful sport performance enhancement (MSPE): A new approach to promote flow in athletes. Journal of Clinical Sport Psychology, 3(4), 334-356. doi: 10.1123/jcsp.3.4.334

Kaufman, K. A., Glass, C. R., & Pineau, T. R. (2018). Mindful sport performance enhancement: Mental training for athletes and coaches. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. doi:10.1037/0000048-000

Kyllo, L. B., & Landers, D. M. (1995). Goal setting in sport and exercise: A research synthesis to resolve the controversy. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 17, 117-137. doi:10.1123/jsep.17.2.117

Landers, D. M., & Arent, S. M. (2010). Arousal-performance relationship. In J.M. Williams (Ed.), Applied sport psychology: Personal growth to peak performance (6th ed., pp. 221-246). Dubuque, IA: McGraw-Hill.

LaPrade, R. F., Agel, J., Baker, J., Brenner, J. S., Cordasco, F. A., Côté, J., … Provencher, M. T. (2016). AOSSM early sport specialization consensus statement. Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine, 4(4). doi:10.1177/2325967116644241

Lundqvist, C., Ståhl, L., Kenttä, G., & Thulin, U. (2018). Evaluation of a mindfulness intervention for Paralympic leaders prior to the Paralympic Games. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 13(1), 62-71. doi: 10.1177/1747954117746495

MacDonald, L. A., Oprescu, F., & Kean, B. M. (2018). An evaluation of the effects of mindfulness training from the perspectives of wheelchair basketball players. Psychology of Sport & Exercise, 37, 188-195. doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2017.11.013

Mammen, G., & Faulkner, G. (2013). Physical activity and the prevention of depression: A systematic review of prospective studies. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 45, 649-657. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.08.001

Mirifar, A., Beckmann, J., & Ehrlenspiel, F. (2017). Neurofeedback as supplementary training for optimizing athletes’ performance: A systematic review with implications for future research. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 75, 419–432. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.02.005

Moore, Z. E. (2009). Theoretical and empirical developments of the mindfulness-acceptance- commitment (MAC) approach to performance enhancement. Journal of Clinical Sport Psychology, 3(4), 291-302. doi: 10.1123/jcsp.3.4.291

Morgan, S. J., & Mora, J. A. M. (2017). Effect of heart rate variability biofeedback on sport performance, a systematic review. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 42(3), 235-245. doi: 10.1007/s10484-017-9364-2

Moritz, S. E., Feltz, D. L., Fahrback, K., & Mack, D. (2000). The relation of self-efficacy measures to sport performance: A meta-analytic review. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 71, 280-294. doi:10.1080/02701367.2000.10608908

Myers, N. D., Feltz, D. L., & Short, S. E. (2004). Collective efficacy and team performance: A longitudinal study of collegiate football teams. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice, 8, 126-138. doi: 10.1037/1089-2699.8.2.126

Myers, N. D., Payment, C. A., & Feltz, D. L. (2004). Reciprocal relationships between collective efficacy and team performance in women’s ice hockey. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice, 8, 182-195. doi: 10.1037/1089-2699.8.3.182

Nideffer, R. M. (1976). Test of attentional and interpersonal style. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 34, 394-404. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.34.3.394

Nideffer, R. M., & Segal, M. (2001). Concentration and attention control training. In J.M. Williams (Ed.), Applied sport psychology: Personal growth to peak performance (4th ed., pp. 312-332). Mountain View, CA: Mayfield.

Post, P., Muncie, S., & Simpson, D. (2012). The effects of imagery-training on swimming performance: An applied investigation. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 24, 323-337. doi:10.1080/10413200.2011.643442

Rebar, A. L., Stanton, R., Geard, D., Short, C., Duncan, M. J., & Vandelanotte, C. (2015). A meta-meta-analysis of the effect of physical activity on depression and anxiety in non-clinical adult populations. Health Psychology Review, 9(3), 1-78. doi:10.1080/17437199.2015.1022901

Rosenbaum, S., Tiedemann, A., Sherrington, C., Curtis, J., & Ward, P. B. (2014). Physical activity interventions for people with mental illness: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 75(9), 964. doi:10.4088/JCP.13r08765

Rumbold, J., Fletcher, D., & Daniels, K. (2012). A systematic review of stress management interventions with sport performers. Sport, Exercise, and Performance Psychology, 1, 173-193. doi:10.1037/a0026628

Santorelli, S. (1999). Heal thy self: Lessons on mindfulness in medicine. New York, NY: Bell Tower.

Schinke, R. J., & McGannon, K. R. (2014). The changing landscape of sport psychology service in Canada. In J. G. Cremades & L. S. Tashman (Eds.), Becoming a sport, exercise, and performance psychology professional: A global perspective (pp. 210-216). New York, NY: Psychology Press.

Schinke, R. J., Si, G., Zhang, L., Elbe, A-M., Watson, J., Harwood, C., & Terry, P. C. (2018). Joint position stand of the ISSP, FEPSAC, ASPASP, and AASP on professional accreditation. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 38, 107-115. doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2018.06.005

Schinke, R. J., Stambulova, N. B., Si, G., & Moore, Z. (2017). International society of sport psychology position stand: Athletes’ mental health, performance, and development. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology. doi:10.1080/1612197X.2017.1295557

Schwartz, M. S., & Andrasik, F. (2017). Biofeedback: A practitioner’s guide: Guilford Publications.

Schwartz, M. S., & Olson, R. P. (2003). A historical perspective on the field of biofeedback and applied psychophysiology. In M. S. Schwartz & F. Andrasik (Eds.), Biofeedback: A practitioner’s guide (3rd ed., pp. 3–19). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Shirazipour, C. H., Evans, M. B., Caddick, N., Smith, B., Aiken, A. B., Martin Ginis, K. A., & Latimer-Cheung, A. E. (2017). Quality participation experiences in the physical activity domain: Perspectives of veterans with a physical disability. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 29, 40-50. doi:10.1016/j.psychsport.2016.11.007

Spence, J. T., & Spence, K. W. (1966). The motivational components of manifest anxiety: Drive and drive stimuli. In C. D. Spielberger (Ed.), Anxiety and behaviour (pp. 291-326). New York, NY: Academic Press.

Stewart, S. (2017, Fall/Winter). Perspectives article: Off the beaten path: A plea for sanctioned sport psychology training in psychology departments. Perseverance, 2017(4), 21-22. Retrieved from https://www.cpa.ca/docs/File/Sections/SportEx/Perseverance%20CPA%20Issue%204%20December%202017_web.pdf

Thompson, M., & Thompson, L. (2015). The neurofeedback book: An introduction to basic concepts in applied psychophysiology (2nd ed.). Oakbrook Terrace, IL: Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback.

Triplett, N. (1898). The dynamogenic factors in pacemaking and competition. American Journal of Psychology, 9, 507-552. doi:10.2307/1412188

Universities Canada. (2018). Member Universities. Retrieved from https://www.univcan.ca/universities/member-universities/