7 Social Psychology

Tara K. MacDonald, PhD, Queen’s University

Valerie Wood, PhD, Queen’s University

Erica Refling, PhD, University of Waterloo

Social Psychology

Social Psychology is the scientific study of how our feelings, our beliefs, and our behaviours are affected by our social environments. Social Psychologists use scientific methods to address issues that have profound importance for individuals and societies. In undergraduate Social Psychology classes, students have the opportunity to learn about diverse topics such as Interpersonal Perception, Attitudes and Persuasion, Conformity and Compliance, Romantic Relationships, Aggression, Altruism, Prejudice, and Discrimination. One of the central themes of Social Psychology is that we are fundamentally motivated to be accepted by, and liked by, others, and maintain our social relationships with others (Baumeister & Leary, 1995). Further, our sense of self is comprised not only of our own unique traits, aptitudes and abilities, but is also based on the social groups to which we belong at a relational (i.e., our friend groups and families) and communal level (e.g., institutions that we belong to, our ethnic and national identities; Tajfel, 1979). These themes of needing to belong and social identity speak to the social nature of humans and can also explain why individuals are so very attuned to, and affected by, their social environments.

Indeed, one of the consistently striking (and sometimes surprising) tenets of Social Psychology is the “Power of the Situation.” For example, key findings in the literature show that one can engineer a situation where typical, everyday citizens agree to hurt a stranger if they are asked to do so by a perceived authority figure (Milgram, 1965; 1974); people will remain in a room that is filling with smoke if there are others in the room who seem unconcerned about the ostensible fire (Latané & Darley, 1968); or be willing to give what they know to be the wrong answer on a test if others around them are giving the wrong answer (Asch, 1955). These highly-cited and well-known findings within Social Psychology are instructive because they demonstrate the potency of our social environment on our behaviour. However, although the argument for the power of the situation is compelling, it’s clear that not everyone reacts in the same way to these situations. For example, although the majority of participants in the Milgram studies agree to administer electric shocks when directed to do so by an authority, some individuals refuse to administer any shocks at all. The variability in individuals’ responses to strong contextual demands also speaks to the important influence of individual differences in determining our behaviour (Funder, 2008). Indeed, our reactions to social situations will vary depending on factors including personality traits (e.g., agreeableness, extraversion), biological factors (e.g., sex, stress reactivity), cultural factors (e.g., the country in which we were raised, our religious beliefs), and other individual differences (e.g., self-esteem, attachment orientation). Further, in addition to these trait differences, our thoughts, feelings, and behaviour can be powerfully affected by the transient states such as mood, cognitive fatigue, or whether specific concepts are cognitively activated at a specific point in time.

In this way, the interactionalist perspective of Social Psychology assesses how these specific characteristics that we might call person variables (e.g., personality traits, individual differences, cultural factors, biological factors, and states) interact with (that is, act together with) situational variables to predict how we will think, feel, and behave. To illustrate, we will provide a specific example of an interaction of this sort. In an interesting study, Crocker, Thompson, McGraw, and Ingerman (1987) assessed whether self-esteem (a trait, or individual difference variable) interacts with group status (a situational variable) to predict in-group favouritism (a tendency to evaluate members of one’s own group positively, and derogate members of an outgroup). They predicted that the effect of group status on the tendency to derogate outgroup members would be especially pronounced for individuals high in self-esteem, relative to those low in self-esteem. Sorority sisters at a large University in the Unites States agreed to participate in the study. In pilot testing, different sororities were rated as being high or low in prestige (status). Approximately half of the participants were from sororities that were rated as low in status, and about half of the participants were from sororities that were rated as high in status. Participants were asked to complete a series of measures including the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (Rosenberg, 1965). They were also asked to rank “typical members” of each of six sororities (including their own sororities) on a number of positive attributes (e.g., attractive, friendly, talented) or negative (e.g., arrogant, boring, unintelligent). For the positive items, the authors found that sorority sisters high in self-esteem were more likely to show ingroup favouritism (that is, assign higher scores on the positive traits for a typical member of their own sorority, relative to typical members of other sororities). There was no effect of group status, and no interaction between self-esteem and group status.

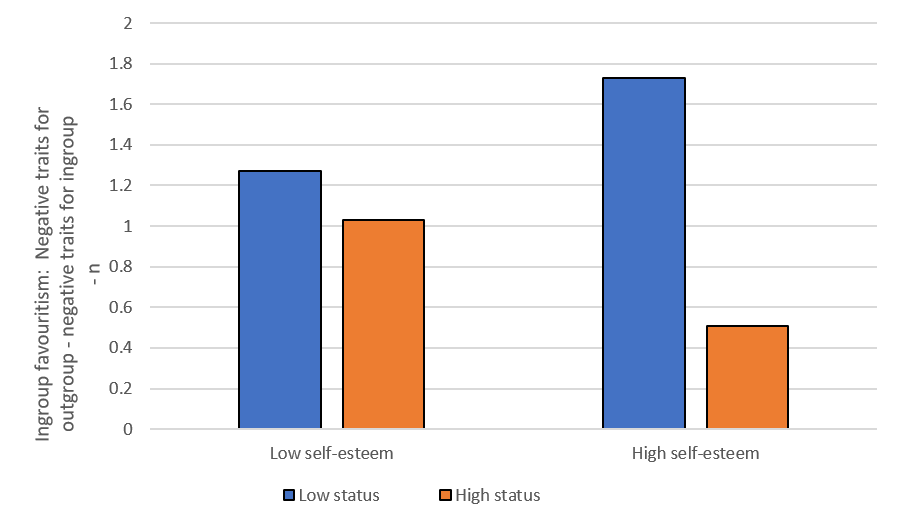

For the negative items, however, a score of ingroup favouritism was derived by subtracting the mean value of negative trait ratings for a typical member of one’s own sorority from the mean value of the negative trait ratings for a typical member of other sororities. In this way, the measure of ingroup favouritism for negative traits meant that participants rated members of other sororities more negatively than they rated members of their own sororities. Crocker and her colleagues found an interaction between self-esteem and group status, such that among those with low self-esteem, there was no difference between those from high or low-status sororities in terms of how much ingroup favouritism they exhibited. Among those with high self-esteem, however, those from low-status groups were more likely to exhibit ingroup favouritism than those from high status groups. The authors state that individuals high in self-esteem may be more likely than their low self-esteem counterparts to react to threat by derogating outgroup members in an effort to maintain their own self-esteem (which is consistent with Social Identity Theory, Tajfel & Turner, 1986).

Here, we can see that a behaviour (ingroup favouritism) is dependent on both person variables (in this case, self-esteem, which is a trait) and situational variables (in this case, group status). An interaction is present, such that the relationship between one variable (group status) and the outcome (ingroup favouritism) is dependent on another variable (self-esteem). Put another way, the results of the study show that the answer to the question “does ingroup favouritism vary as a function of group status?” is “it depends.” It depends on self-esteem: If one is low in self-esteem, then there is no evidence for a relationship between group status and amount of in-group favouritism. However, if one is high in self-esteem, then those from low status groups are more likely to exhibit in-group favouritism than those in high-status groups (see Figure 7.1, below). This example illustrates the way that Social Psychologists can assess research questions by testing interactions between person variables and situational variables, thereby allowing them to understand how different factors combine in complex ways to influence our affect, cognition, and behaviour.

Methods in Social Psychology

Social Psychologists use scientific methods to assess their hypotheses. While a complete review of methodology within Social Psychology would be beyond the scope of this chapter, we will introduce you to some of the primary distinctions among different methodologies used in Social Psychology.

One of the advantages of receiving an undergraduate education in Psychology is that students gain insight into the logic underlying research methodology. There is no “recipe” or step-by-step manual that will allow researchers to conduct a valid study. Instead, research methodology entails a series of decisions, and with every decision there will be some advantages and some disadvantages associated with that decision. Learning about research methodology helps students to understand the implications of these decisions, and how those implications will affect the conclusions that they can draw from their studies. Obviously, this is essential training for students who wish to go on to be scientists and conduct their own research. We argue, however, that an education in research methodology is important and beneficial for all students—for everyone will go on to be a consumer of information. In our everyday lives, we seek information from science. For example, if a family member is diagnosed with a medical condition, it is very common for people to turn to the internet to find out more about that condition. At times, the information can seem confusing or even contradictory. Having a solid grasp of research methodology will help individuals to assess and evaluate scientific research, allowing them to understand the implications of the research decisions that scientists made, which in turn provides a basis to make an informed decision about the validity of the claims reported, and the generalizability of the research to different contexts and populations.

Measurement

In all research, scientists need to measure the variables of interest in their study. The measurement of some variables is relatively straightforward. For example, if one wishes to assess how tall a person is, one would measure the person and record the person’s height in inches or centimetres. In Social Psychology, however, many of the variables we study are psychological constructs that are not directly observable. For example, people will likely agree that traits such as shyness, self-esteem, and intelligence vary amongst individuals (i.e., some people have high self-esteem, others feel more negatively toward the self) that affect our thoughts and behaviour. However, these constructs are not directly or readily apparent, and so researchers must find a way to measure these variables. There are a number of ways to do so. Very briefly, researchers can create a survey or measure to capture these traits (e.g., in 1965 Rosenberg created a 10-item scale to measure self-esteem that is still widely used today). In many cases, such self-report measures are appropriate to use. However, self-report measures can be biased (i.e., people may not want to accurately report their true beliefs, feelings, or behaviour). For example, if a researcher was interested in assessing attitudes and toward academic integrity, and asked the question “Have you ever copied someone else’s work on a test or assignment?” students who have cheated in this way be reticent to admit it, either to avoid being viewed negatively by the researchers, or because they do not want to acknowledge this negative behaviour. This is sometimes called the “Social Desirability Bias.” Further, sometimes people may not be able to answer a self-report question because they simply lack access to the “true” answer. For example, if a student were asked. “What made you decide to study Psychology?” that person may be able to come up with answers that are true in the sense that they are credible reasons that the student believes influenced the decision, but that student may lack access to other factors that could have led to his or her decision to study Psychology (see Nisbett & Wilson, 1977).

If researchers choose not to employ self-report measures, there are a number of tools at their disposal. First, they can choose to directly assess behaviour, or assess a variable that can serve as a proxy for behaviour. For example, if a researcher was interested in assessing condom use behaviour as a dependent variable, the researcher could choose to assess intentions to use condoms with a self-report question (e.g., “I intend to use condoms the next time that I engage in sexual intercourse”). If the researcher was concerned about the social desirability bias, that person could choose to employ a behavioural measure. Of course, it would be impractical (not to mention unethical!) to assess condom use behaviour in the lab. Instead, researchers can choose a proxy for behaviour. For example, Stone and colleagues tested whether inducing hypocrisy (asking participants to publicly stating reasons why condom use is important, and then prompting them to recall instances in the past when they did not use a condom) led to greater condom use than a control condition (who neither publicly stated reasons to use condoms or recalled instances where they did not use condoms), a publicly stating reasons to use condoms only condition, or a recalling instances where they did not use condoms only conditions (Stone, Aronson, Crain, Winslow, & Fried, 1994). For their dependent measure, they assessed condom purchasing behaviour: All participants were paid $4.00 for completing the study, and were given the opportunity to buy condoms for 10 cents each (i.e., participants could choose to spend their earnings to buy condoms). Specifically, 140 condoms were placed in a large glass bowl and there was a plate with dimes in it so that students could “make change” if necessary. Importantly, participants were left alone in the room so that they would have privacy while they purchased the condoms. Consistent with predictions, participants in the hypocrisy condition were more likely to purchase condoms than participants in the other three conditions (control condition, stating reasons to use condoms condition, or recalling past instances where condoms were not used condition). Here, condom purchasing behaviour was used as a proxy variable for condom use behaviour.

In addition to self-report and behavioural/behavioural proxy measures, researchers can use measures that can make inferences about participants’ cognitive processes. Many of these tasks operate under the assumption that if a concept or construct is accessible, we will be faster to recognize that concept, relative to when it is not primed. For example, in the lexical decision task (Meyer & Schvaneveldt, 1971), participants are presented with words on a computer screen (e.g., apple, fight) and non-words (e.g., lopat, gern), and are simply asked to classify them as words or non-words by pressing keys on the keyboard. Their reaction times to make these classifications are recorded (in milliseconds). The logic of the lexical decision task is if participants are “primed” with a concept, they should be faster to recognize words related to that concept than words that are unrelated to that concept. As a simple example, if participants are thinking about aggression, they should be faster to recognize the word “fight” than the word “apple.”

Social Psychologists can use other techniques that employ reaction time data to make inferences about whether individuals hold positive or negative attitudes toward an attitude object using techniques such as the Associative Priming task (APT; Fazio, Jackson, Dunton, & Williams, 1995), the Implicit Attitudes Test (IAT: Greenwald, McGhee, & Schwartz, 1998), and the Affect Misattribution Procedure (AMP: Payne, Cheng, Govorun, & Stewart, 2005). The APT involves showing target images (photos or words) preceding exposure to positively or negatively valenced words. Participants then judge if the word presented was positive or negative. Response times are recorded, with the assumption that responses will be faster if the image and the word were affectively congruent and slower if the target and the words are affectively incongruent. The IAT assesses relative associations between the pairing of a target (in this case, the partner) with positively and negatively valenced words and images, with the logic that if individuals hold a positive attitude toward a target, response speed should be facilitated when the target is associated with positive stimuli, and impeded when the target is associated with negative stimuli. The AMP assesses attitudes toward a target by briefly exposing participants to the target (photos or words) before exposure to ambiguous stimuli (e.g., Chinese characters for non-Chinese readers). Later, participants evaluate the ambiguous stimuli. It has been demonstrated that participants’ attitudes toward the target will be misattributed to the ambiguous stimuli that were paired with the target, such that ratings of these ambiguous stimuli are influenced by their evaluation of the target object.

Sometimes, Social Psychologists are interested in assessing participants’ physiological or neurological reactions to their environment. Put briefly, such measures can be relatively simple such as measuring heart rate or they can require laboratory analysis (e.g., assessing salivary cortisol levels) or complex technology (e.g., neuroimaging techniques such as electroencephalography (EEG, a technique that measures electrical activity in the brain) or functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI, a technique that measures changes in blood flow in the brain).

In general, Social Psychologists often use questionnaires or surveys to assess their constructs of interest. However, the answers participants provide on these explicit, self-report assessments are quite deliberative, and may reflect what the participant believes to be true at a reasoned, conscious level. Further, through the filters of self-report, one’s answers may also reflect biases. For this reason, Social Psychologists can use other measures such as behaviour, proxies for behaviour, cognitive, or physiological measures as assessment tools.

Research Design

Although there are number of ways that one can classify research designs, we will focus on two main types of research methodology that are used in Social Psychology: Non-experimental and experimental research. Non-experimental research seeks to examine whether two (or more) variables are related. Here, variables are measured, and researchers assess the degree of relationship among the variables. For example, if two measures are positively correlated (e.g., higher scores on one variable are associated with higher scores on the other variable), we know that the measures covary such that as one increases, the other increases (e.g., higher self-esteem scores are associated with higher scores of optimism). In contrast, if two measures are negatively correlated, (e.g., higher scores on one variable are associated with lower scores on the other variable), we know that the measures covary such that as one increases, the other decreases (e.g., higher self-esteem scores are associated with lower scores on a depression inventory).

It is important to recognize, however, that in a non-experimental design, a correlation does not necessarily imply causation. Let’s consider, for example, the correlation between playing violent video games (or violent online games) and aggression (see Anderson et al., 2010, for a review of this literature). An example of a non-experimental study might be to recruit a sample of children measure the frequency with which participants play violent video games (either through self-report measures, or programs that track computer activity) as the predictor variable, and measuring aggressive behaviour (for example, through asking teachers or parents to complete measures of aggressive behaviour exhibited by the children) as the outcome variable. In this type of study, both variables (violent video game playing and aggression) are measured, and then researchers use statistics to assess the direction (positive or negative) and the magnitude (strength) of the statistical association between these two variables. Generally, in studies assessing violent video game playing and aggression, researchers find a positive correlation, indicating that the more violent video games that children play, the more likely they are to exhibit aggressive behaviour (Anderson et al., 2010).

What does a positive correlation tell us about the nature of the relationship between playing violent video games and aggression? It may seem that this tells us that playing violent video games causes aggression in children. This may be true, but importantly there are other plausible ways to interpret this relationship. It could also be true that children who are aggressive are more likely to choose to play violent video games than those who are less aggressive. This is another type of causal explanation, but posits that the causality is the other direction (aggressive tendencies lead to greater violent video games). Further, it could be a bi-directional relationship, where both types of causality are true (kids who play violent video games become more aggressive, and kids who are aggressive are more likely to play violent video games). Another possibility is that there is no causal relationship between violent video games and aggression, but that both are linked to a third variable (i.e., the relationship between playing violent video games and aggression is spurious). For example, it could be that compared to children who are more engaged in social activities, those who spend more time alone are more likely to play violent video games, and more likely to engage in aggressive behaviours. If the design of the study is non-experimental (again, this means that the variables are measured, and the researcher assesses the direction and magnitude of the association between the variables), one cannot know whether (a) playing violent video games causes more aggression, (b) kids with aggressive tendencies choose to play violent video games, (c) both causal directions are true, or (d) there is no causal relationship in either direction, but both violent video game playing and aggression are associated with another variable. Students with an education in methodology are trained to evaluate whether the design of a study is non-experimental, and recognize that causality cannot necessarily be inferred.

In experimental research, the goal is typically to identify a causal relationship. Researchers manipulate the independent variable (the presumed causal variable), while holding everything else constant to see if it exerts a change on the dependent variable (the outcome variable). For example, a researcher could select a sample of students from a larger population (e.g., a group of Introductory Psychology students at a University) and recruit them to participate in an experiment. Participants would then be assigned to an experimental condition that allows the researcher to isolate and manipulate the independent variable of interest (in this case, playing violent video games). In this experiment, the researcher might choose to manipulate the independent variable by asking half of the participants play a violent video game, and the other half of the participants to play a non-violent video game. In an experiment, the researcher would be sure to isolate the independent variable by manipulating only the type of video game (violent or non-violent), while holding everything else constant (e.g., all participants would play in the same room, be greeted by the experimenter in the same way, play the video game for the same amount of time). To be sure that it is truly type of video game (and not anything else) that exerts a difference in the dependent variable, the researcher needs to ensure that the only difference between the violent video game condition and the non-violent video game condition is the type of game played.

A second critical feature of experiments is that participants are randomly assigned to condition. Indeed, in our hypothetical experiment, if we gave participants a choice about which game they wished to play, it could be that those who choose to play the violent game are more aggressive than those who choose to play the non-violent game, which would make it impossible to tell whether playing the video game caused differences between the groups, or the groups varied on some other dimension that caused differences between the groups. Instead, through random assignment (where participants are randomly put in one of the two conditions, using a random numbers generator, or some other technique such as flipping a coin to determine which condition the participant will be assigned to), researchers can assume that at the outset of the experiment (i.e., before the manipulation of the independent variable, in this case the type of video game played), the two groups of participants were comparable on all dimensions prior to the experimental manipulation (in this case, playing a violent or non-violent video games), so any difference in the dependent variable observed after the manipulation can be attributed to the independent variable. That is, if we randomly assign students to condition, we can assume that they are comparable on all aspects (including tendency toward aggression) at the start of the experiment. Then, if we manipulate what type of video game they play (half of our sample is randomly assigned to play violent video games, and half of our sample is randomly assigned to play non-violent video games) and hold everything else constant, and we find a difference in our dependent variable, then we can infer that playing violent versus non-violent video games causes an increase in aggressiveness.

In this hypothetical study, the researchers would choose a dependent variable that would measure aggressive behaviour. Here, researchers are faced with an interesting challenge: They need to choose an outcome that is a valid operationalization of aggression that can be measured in a realistic and ethical way. Researchers can use self-report measures (such as the Conflict Tactics Scale, Straus, 1979), or scenario completion measures, where participants read about a hypothetical situation and are asked what they would do if faced with that scenario. These types of self-report measures are well-suited for some types of dependent measures, but as discussed above, in the case of aggression, people may be unwilling to say that they would respond with aggression because of the social desirability bias. Instead, researchers may choose to engineer a social situation in the laboratory that allows for the assessment of aggressive behaviour (for reviews see DeWall et al., 2013; McCarthy & Elson, 2018). Social psychologists studying aggression have employed techniques including administering (fake) electric shocks to a partner (e.g., Berkowitz & LePage, 1967; Taylor, 1967), administering blasts of loud noise to a partner (e.g., Anderson & Dill, 2000; Bushman & Baumeister, 1998), choosing how long a partner must hold their hand in a tub of very cold water (e.g., Pederson, Vasquez, Bartholow, Grosvenor, & Truong, 2014), choosing the difficulty level of yoga poses a partner must hold and the amount of time in these poses (e.g., Finkel, DeWall, Slotter, Oakten, & Foshee, 2009), choosing how much hot sauce to put on mashed potatoes that a partner must eat (e.g., Lieberman, Solomon, Greenberg, & McGregor, 1999; Warburton, Williams, & Cairns, 2006), or counting the number of pins that participants stick in a doll that represents a partner (e.g., Voodoo doll task, Slotter et al., 2012). Some of these tasks might seem far-fetched at first glance, but many have been demonstrated to be valid and reliable measures of aggression; for example, DeWall and colleagues (2013) conducted nine studies demonstrating that the Voodoo doll task correlates with measures of trait aggression, self-reported history of aggression, other accepted laboratory measures of aggressiveness such as administering louder and more prolonged blast of noise, and is reasonably consistent over time. Thus, DeWall and colleagues have used scientific method to demonstrate the validity of using this task to measure aggression.

To review, we have focused on how two principles of experimentation, isolation and manipulation of an independent variable and random assignment of participants to experimental condition, allow researchers to determine whether one variable (the independent variable) causes a change in an outcome variable (the dependent variable). It is important to note that finding that a variable causes a change in the dependent variable does not necessarily imply that reverse causality is not true as well. It could be that the causal direction works in both ways. Further, even if researchers do show that one independent variable causes a change in the dependent variable, it is important to note that this does not imply that the independent is the only cause of the dependent variable—there may be many potential variables that can cause a change in the dependent variable.

We have also commented on the challenges posed to researchers as they seek to measure constructs that cannot be directly observed, and as they attempt to manipulate variables in the laboratory. Some variables cannot be experimentally manipulated, because it would not be possible to manipulate the construct of interest. For example, if a researcher is interested in assessing a trait variable such as extraversion as a predictor variable, it is not possible to randomly assign people to be high or low in extraversion. Further, if a researcher is interested in assessing whether the individuals with siblings are more communicative than only children, one cannot randomly assign people to the sibling or non-sibling conditions—we either have siblings or we don’t. In other cases, it isn’t ethical to randomly assign people to condition; for example, there are many restrictions in place about administering potentially harmful substances to participants (e.g., some universities do not allow any study involving the administration of alcohol, those that do allow it have procedures and restrictions in place to ensure that the administration is safe). When it is impossible or unethical to manipulate an independent variable, social psychologists rely on non-experimental research, but are careful not to draw conclusions about causality.

Students of Social Psychology often enjoy learning about the clever and creative ways that researchers operationalize very dynamic “real-world” experiences in a way that can be concretely and ethically manipulated in the laboratory. As just one example, psychologists have conducted research assessing the profound ways that experiences of ostracism and social rejection affect our mental and physical health (for reviews, see Williams, 2001; DeWall & Bushman, 2011). Most people would agree that empirically studying the effects of social rejection on outcomes is a worthwhile goal. However, how can Social Psychologists manipulate rejection in a way that is (a) powerful enough to simulate the experience of rejection in the “real world” and (b) ethical, so that participants are treated with respect and there is no lasting harm? Researchers have developed a number of clever paradigms to manipulate rejection, so that participants can be randomly assigned to a rejection or non-rejection condition, allowing researchers to assess the extent to which rejection exerts a change in the dependent variable. In one commonly employed paradigm called “Cyberball” (Williams, Cheung, & Choi, 2000; Williams & Jarvis, 2006 ), participants are led to believe that they are playing an online game of “catch” with two other participants who are represented by avatars. Participants are told that when they receive the ball, they can choose who to “throw” it to by clicking on the avatar of the intended ball recipient. In reality, they are not actually playing with real people, but are interacting with a computer program. In the non-rejection condition, participants receive and throw the ball approximately one-third of the time, so they receive equal time with the ball, relative to the other two (computer-generated) “players”. In the rejection condition, however, participants initially receive the ball, but over time, the other two “players” start to exclude the participant from the game, tossing the ball only to each other, thereby ignoring the participant. Interestingly, idea of the Cyberball paradigm originated with an actual experience that the creator of the paradigm, Kip Williams, had when he started playing Frisbee with two strangers, but then was excluded from the game. At first glance, one might assume that any rejection that one might experience by being excluded by two strangers during an online ball-toss game would be so mild as to be inconsequential. However, the experience of exclusion and rejection in the Cyberball paradigm is quite powerful, and there is evidence showing that relative to the non-rejected Cyberball condition, those in the rejection condition exhibit outcomes such as lower levels of self-esteem, more negative mood states, poorer performance on a cognitive task, greater susceptibility to social influence techniques, and more aggression (for reviews, see Gerber & Wheeler, 2009; Hartgerink, van Beest, Wicherts, & Williams, 2015). This provides an example of a powerful, “real world” phenomenon (rejection and ostracism) that can has been distilled to an experimental manipulation that can be readily employed in the lab (participants can be randomly assigned to condition). Although the short-term effects of Cyberball are impactful, it is an ethical design to use, as the participants can be easily debriefed (informed of the purpose of the study, and any deception that occurred during the study) and told that they were not actually being excluded.

Applications of Social Psychology

One of the reasons that the scientific study is so appealing and exciting is that what students learn is so readily applicable to their own lives. Students of Social Psychology gain insight into processes and factors affecting our thoughts, feelings, and behaviour. It is intriguing and instructive to learn about why we systematically (and repeatedly!) make errors in our judgments, attributions, and predictions (how many times do we underestimate how long it will take us to complete a task such as writing an essay?) (Buehler, Griffin, & Ross, 1994). Students can usually relate to examples of how they have been influenced by compliance techniques (Cialdini, 2009), such as the scarcity principle, which is when items seem more valuable when they are viewed as rare or hard to get (e.g., becoming more interested in purchasing a product when told “Act now, they are selling out fast!”). Further, social psychology can often provide students with theoretical frameworks that give insight to their own social behaviours. For example, learning about adult attachment orientations (see Hazan & Shaver, 1987; Mikulincer & Shaver, 2012) can help students to understand their own tendencies to react in specific ways within the context of their romantic relationships, and potentially use this increased understanding to improve their own relationships (e.g., understanding how attachment can influence conflict behaviour can help students recognize problematic patterns and respond more constructively when conflict arises). Finally, there is some research assessing the effects of “enlightenment” on future behaviour; meaning that learning about findings in Social Psychology can influence how we react to situations in our daily lives. For example, there is evidence to suggest that learning about the Milgram obedience study can lead to greater cognitive moral development among university students (Sheppard & Young, 2007).

Social Psychology is also very useful in its application to society. Much of the basic research that is conducted can have practical benefits. For example, if scientists understand factors that predict a pattern of behaviour, and the identify the mechanisms underlying the relationship between predictors and outcomes, this knowledge can be applied to help encourage positive behaviours (e.g., increasing the efficacy of campaigns designed to encourage people to vote, volunteer, recycle, or exercise) and prevent harmful behaviours (e.g., reduce the likelihood of workplace aggression, bystander apathy, drinking and driving, or academic dishonesty). Social Psychology can be applied to a variety of contexts including the workplace (e.g., what variables predict employee commitment to their organization?), the classroom (e.g., how can teachers motivate students to persevere when they face challenges?), sports and athletics (e.g., when is a team most likely to exhibit the ‘home-field advantage?), and the military and government (i.e., what types of leadership is most effective in different contexts?). Again, a thorough review of all of the possible applications of social psychology would be beyond the scope of this chapter, but we will provide you with some illustrative examples (see also Gruman, Schneider, & Coutts, 2016; Myers, Spencer, & Jordan, 2018).

Social Psychology and Health

There are many ways that Social Psychological principles can be applied to health behaviours. For example, understanding persuasion and social influence can be applied to helping public health associations frame their messages so that their campaigns will be effective in encouraging healthy behaviours. This type of “Social Marketing” expertise is used to apply principles of persuasion and compliance in a way that will benefit individuals and society. For example, researchers have studied individual difference and contextual variables that influence the efficacy of framing a health behaviour in a way that emphasizes promotion (e.g., “eating fruits and vegetables can help maintain good health”) or prevention (e.g., eating fruits and vegetables can help prevent various types of cancers”; see Rothman & Salovey, 1997).

Further, many widely applied theories in Health Psychology are based on core findings in Social Psychology. For example, the Theory of Planned Behaviour (Ajzen, 1991) is a theoretical model that can be used to predict a variety of behaviours, including health behaviours. It states that one’s behavioural beliefs (whether we think our behaviours will produce certain outcomes, and our evaluation of those outcomes), subjective norms (whether we think that other will approve or disapprove of our behaviour, and our motivation to comply with their preferences), and perceived behavioural control (whether we think it is likely that we will be able to enact the behaviour) combine to form our intentions. Our intentions then predict our behaviour. This theory is readily applied to decisions to engage in a wide range of health behaviours, such as starting an exercise program, quitting smoking, or eating a more healthy diet. The Theory of Planned Behaviour also speaks to social influences on our decision-making, by positing that subjective norms are one of the three primary factors that influence our intentions to engage in behaviours.

Other researchers have applied Social Psychological principles to factors that promote mental health. Students of Social Psychology often find it amusing when they learn about biases, or “Positive Illusions” that individuals tend to hold about themselves (Taylor & Brown, 1988; Taylor, 1991). Indeed, researchers have established that non-depressed individuals make systematic errors when they make judgments about themselves. For example, individuals tend to rate themselves more positively than most other people would rate them (e.g., most people think that they are a better than average driver), they overestimate the degree of control they have over their environments, and they make unrealistically optimistic predictions about their futures (e.g., long it will take them to complete tasks, how long their romantic relationships will endure). Taylor and her colleagues have shown that these “illusions”—these consistent errors in judgment that we make about ourselves and our daily lives—are correlated with greater self-esteem, well-being, and health. In contrast, being realistic about our standing on various attributes or our chances of success is sometimes referred to as “depressive realism” (Alloy & Abramson, 1979).

Other Social Psychologists have investigated the extent to which health is associated with the presence of, and quality of, our close relationships. There is much evidence to support the hypothesis that people who feel connected to others and report high levels of satisfaction with their close relationships are likely to enjoy better mental health, better physical health, and longer lives (House, Landis, & Umberson, 1988). Interestingly, relative to those who have close and rewarding relationships with others, those who are lonely or isolated are more likely to exhibit poorer self-reported health (Fees, Martin, & Poon, 1999), increased risk of heart attack (Case, Moss, Case, McDermott, & Eberly, 1992), worse blood pressure regulation (Uchino, Cacioppo, & Kiecolt-Glaser., 1996), poor sleep efficiency (Cacioppo et al., 2002), worse cardiovascular functioning (Hawkley, Burleson, Berntson, & Cacioppo, 2003), and worse immune functioning (Kiecolt-Glaser et al., 1984). As an illustrative example, Pressman and colleagues (2005) invited 83 healthy first-year university students to participate in a study. They completed a variety of self-report measures to assess loneliness, depression, neuroticism, and health behaviours. They were also given a flu shot. The mechanism behind a flu shot is that a dormant version of the virus is injected, and in response, the immune system “kicks in” and produces antibodies, which will then be in place should a person contract the flu virus. Individuals with more healthy immune systems produce more antibodies in response to a vaccine than those with less optimal immune functioning. To test immune function, participants returned to the lab 1 month and 4 months after receiving their flu shot, and their blood was tested for flu antibodies. There was a negative correlation between loneliness and antibodies present in the blood, such those who reported more loneliness had fewer flu antibodies relative to those who were less lonely. Interestingly, the correlation between loneliness and flu antibodies was still evident after controlling for the effects of depression, health behaviours and neuroticism. Studies such as these demonstrate the importance of social relationships for not just our mental health, but our physical health as well. Further, social and health psychologists have worked to identify the mechanisms underlying the association between satisfying relationships and physical health.

Social Psychology and the Legal System

Social Psychology can be readily applied to many aspects of the legal system. First, many cases are often tried by jury. A jury is a group of citizens tasked with reviewing evidence presented by both the prosecution and the defense team, and deciding whether a defendant is guilty. Many times, the jurors do not initially agree on a verdict, but after deliberation, about 95% of juries agree (Kalven & Zeisel, 1966). Social psychologists study relevant concepts such as majority influence (a common phenomenon when a numerical majority can persuade a numerical minority) and minority influence (a less common phenomenon such that when specific conditions are met, a numerical minority can persuade a numerical majority). Indeed, the classic movie “12 Angry Men” (Fonda, Justin, Rose, & Lumet, 1957 , a movie which depicts a lone juror eventually persuading his 11 fellow jury members to reconsider their initial decision) is often shown in classes as a demonstration of the processes underlying minority influence.

Eyewitness testimony is when people who witnessed an event describe what they remember, and this is presented as evidence to the court. Social psychologists study processes such as how our attitudes and expectations can influence what we notice about an event, how we interpret an event, and what we remember about an event. There are many factors that can cause individuals to make errors at each step in this sequence (attention, encoding, and retrieval), and psychologists have studied factors that influence the veracity of eyewitness testimony. Interestingly, the cues that jurors use to make decisions about the credibility of eyewitnesses are sometimes unrelated, or even inversely related, to their accuracy. For example, Wells and Leippe (1981) found that jurors deem witnesses who can provide extensive details of background variables of the crime scene to be more credible than witnesses less able to provide such descriptions. However, in reality, witnesses who can describe background details have been found to be less accurate at identifying a perpetrator than those who cannot recall background details.

Social Psychology and the Workplace

Social Psychology is closely related to Industrial-Organizational Psychology, which is a field where researchers study workplace behaviour. Principles of Social Psychology can be applied to benefit the organization (e.g., assessing factors associated with increased productivity, efficiency, and employee commitment and loyalty) and the employees (e.g., assessing factors associated with workplace satisfaction, group morale, and the physical and mental health of employees). Further, the study of personality and individual differences can be applied to employee recruitment and personnel selection.

Many workplaces involve working collaboratively with other individuals or on teams. As such, core topics in Social Psychology such as social influence, conformity, group decision-making, interpersonal relationships, altruism, and aggression can all be applied to the goal of making workplaces effective, satisfying, and safe. For example, social Psychologists have studied topics such as Social Loafing (the tendency to work less hard on a group task relative to the effort that is expended when people work individually; Latané, Williams, & Harkins, 1979), Group Polarization (the tendency for groups to make decisions that are more extreme than the individual members’ starting position; Moscovici & Zavalloni, 1969) and Groupthink (the tendency for individuals in groups to be concerned with agreeing with the group, instead of raising disparate opinions; Janis, 1971). Importantly, Social Psychologists have not only studied these group processes that can potentially undermine organizational efficiency, but they have studied ways to mitigate and prevent these processes.

Most workplaces employ leaders or managers at different levels who are responsible for motivating their teams to work productively and achieve goals, facilitating communication and positive relationships among group members, and provide performance feedback to their group members. Industrial-Organizational Psychologists assess factors that make a good leader, different leadership styles (i.e., task leadership, transactional leadership, and transformational leadership) and the types of leadership that are most effective depending on the context (e.g., contingency leadership; Fiedler, 1967). In the workplace, this research can be applied to leadership training and promotion decisions.

Interestingly, some of the core theories that have been advanced in the Interpersonal Relationships literature can be applied to the workplace. For example, the Investment Model (Rusbult, 1980) was introduced to the literature to explain commitment to a romantic relationship. Specifically, Rusbult posited that commitment to a relationship is determined by three predictors: Satisfaction, Investments, and Alternatives. Satisfaction refers to the presences of positive aspects, and the absence of negative aspects in our relationship, such that we are more likely to stay in a relationship if we find it satisfying. This seems straightforward, but we can all think of examples where people stay in romantic relationships even though they do not seem satisfied. Why might this be? The other two factors can explain why people would remain in relationships that aren’t making them happy. Investments refers to intangible or tangible things that we have put into a relationship that we will not recover if the relationship were to end (e.g., resources such as money, time put into the relationship, sacrifices we have made for the sake of the relationship). People who have invested more in their relationship are more committed. Finally, alternative refers to what we think our life would be like without the relationship (e.g., being single, being with a new (unknown) partner, or being in a relationship with a specific person that we think would be a potential new partner). If people believe that their current relationship is better than other relationships that they are likely to find (or being single), then they are likely to stay committed to the relationship. Interestingly, these same factors can be applied to whether we stay committed to our workplaces (Farrell & Rusbult, 1981; Oliver, 1990). When making stay or leave decisions, we consider our satisfaction with the workplace (e.g., “do I like coming to work? Am I fulfilled by this job”), the investments we have made (e.g., “will I lose my pension if I leave? Can I walk away from a place I have worked for 20 years?”), and the alternatives that we have (e.g., “Can I afford to be unemployed for a while? Will I be more fulfilled by taking this new position that has become available?).

Careers in Social Psychology

The scientific study of how our thoughts, feelings, and behaviours are influenced by our social situations can help us understand, and relate to, others. Moreover, students with an undergraduate degree in Psychology typically receive strong training in research methodology and statistics, which are highly transferrable skills. Further, the study of Psychology entails not only rigorous methodological and statistical competencies, but higher-order conceptual and analytical skills. In particular, psychology students are taught to evaluate findings and observations from larger theoretical frameworks, to question underlying mechanisms for observed relationships, and identify the core underlying principles that guide our thoughts and behaviours. In other words, students of psychology are able to leverage a conceptual understanding of human behaviour, in addition to more specific research-related skillsets. For these reasons, psychology students are ideal candidates for a number of critical industry positions that require an understanding of industry-relevant human behaviour or functioning, using sound methodologies and analyses.

There are number of entry-level positions for students with an undergraduate degree in Psychology. Just a few examples include research analyst, policy analyst, research or lab assistant, and organizational development assistant/human resources advisor.

Research Analyst

A number of industry and governmental agencies (e.g., marketing, health) require research analysts to help them conduct research relevant to their field and organizational mandate. Analysts may either assist the research activities of more senior analysts, or may organize and conduct their own research activities including survey development, data collection, data analysis, report writing, and producing or delivering presentations. This may include an assessment of the organization’s internal database, or the collection of data external to the organization. Analysts may be asked to use their findings to make policy or program recommendations, depending on the nature of the research, the organization, and one’s position.

Policy Analyst

The research skills of psychology graduates can also be used to inform policy (e.g., education and health sectors). Policy analysts use evidence-informed research to develop short-term and long-term policies and procedures for the relevant agency. Some of these duties would overlap with those of a research analyst, but with the additional tasks of using research to inform policy development, which could include training materials and guides that support those policies.

Research or Lab Assistant

Students with an undergraduate degree in Psychology can apply their research skills by working in a lab as a research assistant at a university, hospital, or research agency. Research assistants typically work with graduate students and researchers by recruiting participants for research studies, collecting data, analyzing data, and helping to summarize the research for presentations or publications.

Organizational Development Consultant/ Human Resources Advisor

There are some positions within human resource departments that don’t require an advanced degree, and that utilize many of the skills and competencies acquired by undergraduates in psychology. In particular, psychology students can work as consultants in a human resources department in industry, or within an organizational development firm. Organizational development as a field involves the application of social psychological principles to help improve employee and organizational performance and effectiveness. Specifically, organizational developers help to produce change in an institution’s systems, structures and processes, including the employees working within those systems. The process of organizational development typically includes a diagnosis of organizational problems and current functioning through collection and analysis of data, designing and implementing interventions for change, and evaluating the effectiveness of those interventions afterwards (Cummings & Worley, 2009). Human resources advisors involve the application of research and statistical competencies in the recruitment and selection of personnel, employee training and development, and performance assessment and management (Boxall, Purcell, & Wright, 2007).

Polling Firms

As part of an undergraduate education in Psychology, many students learn about survey design and test construction. This skill set can be applied to work at Polling firms (e.g., Gallup, Ipsos, Angus Reid), where employees plan and design surveys and test instruments, conduct research to assess the psychometric properties of the instruments, collect data, and then analyze and summarize the data for presentation to the client. In this way, working at a polling firm is specific type of consulting, specializing in test and survey construction, validation, and analysis. Similar types of jobs can also be found in Provincial and Federal levels of Government (e.g, Statistics Canada).

Market Research

Market researchers use their research training to help companies become more productive and profitable by making sound economic, political, and social decisions. They monitor and forecast sales trends, and collect data about customers. For example, they may design surveys or conduct focus group research to assess customer satisfaction, marketing strategies, corporate branding, or factors that affect customer loyalty. They analyze these data, summarize their findings, and prepare reports to inform businesses how to best market their products or services.

Consulting Careers

Consultants use their skills, expertise, and knowledge to help individuals or organizations with a specific goal. One can work for a large consulting firm as a consultant or project manager (e.g., Bain, Accenture, Ipsos). It is also possible to specialize further to a specific type of consulting work. There are examples of specific people who work in consulting (and their education and career trajectories) available online via the webpage of the American Psychological Association (www.apa.org). Specific examples of consultants include (but are not limited to) Trial Consultant, Media Consultant. Medical Error Consultant, Market Consultant, Executive Search Consultant, and Organizational Development Consultant.

Further Education in Social Psychology and Related Fields

Students who obtain an undergraduate degree in Psychology are eligible for a number of training paths that would require further education. For example, students with a background in Social Psychology can go to professional schools, such as law school or business school.

In addition to these professions, students can also pursue graduate training in Psychology or related disciplines. Students with an undergraduate degree in Psychology can go on to attain a Master’s of Science (M.Sc.), Master’s of Arts (M.A.) or Doctoral degree (PhD) in Psychology. Typically, at the graduate level, students will specialize in a specific field or subdiscipline within Psychology (e.g., Social Psychology. Clinical Psychology, Developmental Psychology, Cognitive Psychology, Organizational Psychology, Neuropsychology, etc.). With a background in Psychology, it is also possible to seek graduate training in closely related programs outside of Psychology (e.g., graduate degrees in Education, Social Work, Counselling, Public Health, Public Policy, Epidemiology, or Marketing).

Career Paths for Those with MA/MSc/PhD in Social Psychology

Academic Positions

Many students who graduate with a PhD in Social Psychology go on to work as a Faculty member or Lecturer at Colleges or Universities. Faculty members (professors) conduct and publish research to advance the field of social psychology, supervise graduate and undergraduate student research activities, teach at the undergraduate and graduate levels, and are responsible for administrative duties. Lecturers typically focus on teaching duties, by utilizing their knowledge of research methods and social psychological principles to teach courses at the undergraduate and graduate levels. Although many individuals with graduate training in Social Psychology go on to work in academic positions within Psychology Departments, others hold Faculty or Lecturer positions in other departments, such as Business Schools, Education, Health Studies, Political Science, and Policy Studies

Research Positions Outside of Academia

Graduate training in Social Psychology can prepare students for a wide variety of research jobs outside of universities or colleges. Some examples are described below.

Defence Scientists

Defense Scientists work for governmental agencies like the Department of National Defence or Defence Research and Development Canada. They conduct research on the Canadian Armed Forces including their well-being and operational effectiveness. Defence scientists have the opportunity to address a variety of operational problems with their research, and see the real-world impact their research has made on the lives of CAF personnel and decision making within the Department of National Defence. The use of theoretical frameworks, in addition to quantitative methodological and statistical competencies, can be appealing and very relevant for this type of research, making social psychology students desirable candidates for such positions.

Further, all of the examples of career paths described as possible trajectories for individuals with an undergraduate education in Psychology (e.g. careers in Consulting, Policy Analysis, Market Analysis, Polling, Research Analysis, or Organizational Behavior) are also very good options for those with advanced degrees in Social Psychology. A graduate degree makes it possible to apply for positions that are higher than entry-level jobs, so a greater degree of options in these exciting career paths are available to those with a graduate degree.

Growth Careers in Social Psychology

There is a good reason to be optimistic about the job market for students with a degree in Social Psychology. Understanding how people are influenced by their social environments, combined with the excellent training in research methodology and statistics, makes students with expertise in Social Psychology attractive to a number of different types of employers, such as those mentioned above. Further, according to the American Psychological Association (www.apa.org), there will be career sector growth in related fields such as program evaluation, working with older adults, the military, and the government.

References

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50, 179-211.

Alloy, L. B., & Abramson, L. Y. (1979). Judgment of contingency in depressed and nondepressed students: Sadder but wiser? Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 108, 441-485.

Anderson, C. A., & Dill, K. E. (2000). Video games and aggressive thoughts, feelings, and behavior in the laboratory and in life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78, 772-790.

Anderson, C. A., Shibuya, A., Ihori, N., Swing, E. L., Bushman, B. J., Sakamoto, A., . . . Saleem, M. (2010). Violent video game effects on aggression, empathy, and prosocial behavior in Eastern and Western countries: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 136, 151-173.

Asch, S. E. (1955). Opinions and social pressure. Scientific American, 193, 31–35.

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117, 497-529.

Berkowitz, L., & LePage, A. (1967). Weapons as aggression-eliciting stimuli. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 7, 202-207.

Boxall, P. F., Purcell, J., & Wright, P. M. (2007). The Oxford handbook of human resource management. London, UK: Oxford University Press.

Buehler, R., Griffin, D., & Ross, M. (1994). Exploring the “planning fallacy”: Why people underestimate their task completion times. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67, 366-381.

Bushman B. J., & Baumeister R. F. (1998). Threatened egotism, narcissism, self-esteem, and direct and displaced aggression: Does self-love or self-hate lead to violence? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75, 219–229

Cacioppo, J. T., Hawkley, L. C., Bernston, G. C., Ernst, J. M., Gibbs, A. C., Stickgold, R., & Hobson, J. A. (2002). Do lonely days invade the nights? Potential social modulation of sleep efficiency. Psychological Science, 13, 384-387.

Case R. B., Moss A. J., Case N., McDermott M., & Eberly S. (1992). Living alone after myocardial infarction. Impact on prognosis. Journal of the American Medical Association, 267, 515–519.

Cialdini, R. B. (2009). Influence: Science and practice. Boston, MA: Pearson Education.

Crocker, J., Thompson, L. L., McGraw, K. M., & Ingerman, C. (1987). Downward comparison, prejudice, and evaluations of others: Effects of self-esteem and threat. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 907–916.

Cummings, T. G., & Worley, C. G. (2009) Organization development & change (9th ed.). Mason, OH: South Western Cengage Learning.

DeWall, C. N., & Bushman, B. J. (2011). Social acceptance and rejection: The sweet and the bitter. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 20, 256–260.

DeWall, C. N., Finkel, E. J., Lambert, N. M., Slotter, E. B., Bodenhausen, G. V., Pond, R. S., … Fincham, F. D. (2013). The voodoo doll task: Introducing and validating a novel method for studying aggressive inclinations. Aggressive Behavior, 39, 419-439.

Farrell, D., & Rusbult, C. E. (1981). Exchange variables as predictors of job satisfaction, job commitment, and turnover: The impact of rewards, costs, alternatives, and investments. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 28, 78-95.

Fazio, R. H., Jackson, J. R., Dunton, B. C., & Williams, C. J. (1995). Variability in automatic activation as an unobtrusive measure of racial attitudes: A bona fide pipeline? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69, 1013–1027.

Fees, B. S., Martin, P., & Poon, L. W. (1999). A model of loneliness in older adults. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 54, 231-239.

Fiedler, F. (1967). A theory of leadership effectiveness. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Finkel, E. J., DeWall, C. N., Slotter, E. B., Oaten, M., & Foshee, V. A. (2009). Self-regulatory failure and intimate partner violence perpetration. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 97, 483-499.

Fonda, H. (Producer), Justin, G. (Associate Producer), Rose, R. (Producer), & Lumet, S. (Director). (1957). 12 angry men [Motion Picture]. USA: Orion-Nova Productions.

Funder, David C. (2008). Persons, Situations, and Person–Situation Interactions. In Handbook of Personality: Theory and Research, Eds. John, Oliver P., Robins, Richard W., & Pervin, Lawrence A. . New York: Guilford Press, 568–80.

Gerber, J., Wheeler, L. (2009). On being rejected: A meta-analysis of experimental research on rejection. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 4, 468–488.

Greenwald, A. G., McGhee, D. E., & Schwartz, J. L. K. (1998). Measuring individual differences in implicit cognition: The Implicit Association Test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 1464- 1480.

Gruman, J., Schneider, F., & Coutts, L. (Eds.). (2016). Applied social psychology: Understanding and addressing social and practical problems (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Hartgerink, C. H., van Beest, I., Wicherts, J. M., & Williams, K. D. (2015) The ordinal effects of ostracism: a meta-analysis of 120 cyberball studies. PLoS ONE 10:e0127002.

Hawkley, L. C., Burleson, M. H., Berntson, G. G., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2003). Loneliness in everyday life: Cardiovascular activity, psychosocial context, and health behaviors. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85, 105-120.

Hazan, C., & Shaver, P. (1987). Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 511-524.

House, J. S., Landis, K. R., & Umberson, D. (1988). Social relationship and health. Science, 241, 540-545.

Janis, I. L. (1971). Groupthink. Psychology Today, 5, 43-46.

Kalven, H., & Zeisel, H. (1966). The American jury. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Kiecolt-Glaser, J. K., Garner, W., Speicher, C., Penn, G. M., Holliday, J., & Glaser, R. (1984). Psychosocial modifiers of immunocompetence in medical students. Psychosomatic Medicine, 46, 7-14.

Latané, B., & Darley, J. M. (1968). Group inhibition of bystander intervention in emergencies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 10, 308–324.

Latané, B., Williams, K., & Harkins, S. (1979). Many hands make light the work: The causes and consequences of social loafing. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37, 822-832.

Lieberman, J. D., Solomon, S., Greenberg, J. L., & McGregor, H. A. (1999). A hot new way to measure aggression: Hot sauce allocation. Aggressive Behavior, 25, 331-348

McCarthy, R. J., & Elson, M. (2018). A conceptual review of lab-based aggression paradigms. Collabra: Psychology, 4, 1-12.

Meyer, D. E., & Schvaneveldt, R. W. (1971). Facilitation in recognizing pairs of words: Evidence of a dependence between retrieval operations. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 90, 227-234.

Mikulincer, M., & Shaver, P. R. (2012). Attachment theory. In P. Van Lange, A. Kruglanski, & E. Higgins (Eds.), Handbook of theories of social psychology. (pp. 160-180). London, UK: SAGE Publications Ltd.

Milgram, S. (1965). Some conditions of obedience and disobedience to authority. Human Relations, 18, 57-76.

Milgram, S. (1974). Obedience to authority: An experimental view. New York: Harper Collins.

Moscovici, S., & Zavalloni, M. (1969). The group as a polarizer of attitudes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 12, 125-135.

Myers, D. G., Spencer, S. J., & Jordan, C. H. (2018). Social Psychology (7th Canadian ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Nisbett, R. E., & Wilson, T. D. (1977). Telling more than we can know: Verbal reports on mental processes. Psychological Review, 84, 231-259.

Oliver, N. (1990). Rewards, investments, alternatives and organizational commitment: Empirical and evidence and theoretical development. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 63, 19-31.

Payne, B. K., Cheng, C. M., Govorun, O., & Stewart, B. D. (2005). An inkblot for attitudes: Affect misattribution as implicit measurement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 89, 277-293.

Pederson, W. C., Vasquez, E. A., Bartholow, B. D., Grosvenor, M., & Truong, A. (2014). Are you insulting me? Exposure to alcohol primes increases aggression following ambiguous provocation. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 40, 1037–1049

Pressman, S. D., Cohen, S., Miller, G. E., Barkin, A., Rabin, B. S., & Treanor, J. J. (2005). Loneliness, social network size, and immune response to influenza vaccination in college freshman. Health Psychology, 24, 297-306.

Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Rothman, A. J., & Salovey, P. (1997). Shaping perceptions to motivate healthy behaviour: The role of message framing. Psychological Bulletin, 121, 3-19.

Rusbult, C. E. (1980). Commitment and satisfaction in romantic associations: A test of the investment model. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 16, 172-186.

Sheppard, J. P., & Young, M. (2007) The routes of moral development and the impact of exposure to the Milgram obedience study. Journal of Business Ethics, 75, 315–333.

Slotter, E. B., Finkel, E. J., DeWall, C. N., Pond, R. S., Jr., Lambert, N. M., Bodenhausen, G. V., & Fincham, F. D. (2012). Putting the brakes on aggression toward a romantic partner: The inhibitory influence of relationship commitment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 102, 291-305.

Stone, J., Aronson, E., Crain, A. L., Winslow, M. P., & Fried, C. B. (1994). Inducing hypocrisy as a means of encouraging young adults to use condoms. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 20, 116-128.

Straus, M. A. (1979). Measuring intrafamily conflict and violence: The Conflict Tactics (CT) scales. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 41, 75-88.

Tajfel, H. (1979). Individuals and groups in social psychology. British Journal of Social, & Clinical Psychology, 18, 183-190.

Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1986) The Social Identity Theory of Intergroup Behavior. Psychology of Intergroup Relations, 5, 7-24.

Taylor, S. (1967). Aggressive behavior and physiological arousal as a function of provocation and the tendency to inhibit aggression. Journal of Personality, 35, 297–310.

Taylor, S. E. (1991). Positive illusions: Creative self-deception and the healthy mind. New York: Basic Books.

Taylor, S. E., & Brown, J. (1988). Illusion and well-being: A social psychological perspective on mental health. Psychological Bulletin, 103, 193–210.

Uchino, B. N., Cacioppo, J. T., & Kiecolt-Glaser, J. K. (1996). The relationship between social support and physiological processes: A review with emphasis on underlying mechanisms and implications for health. Psychological Bulletin, 119, 488-531.

Warburton, W. A., Williams, K. D., & Cairns, D. R. (2006). When ostracism leads to aggression: The moderating effects of control deprivation. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 42, 213–220.

Wells, G. L., & Leippe, M. R. (1981). How do triers of fact infer the accuracy of eyewitness identifications? Using memory for peripheral detail can be misleading. Journal of Applied Psychology, 66, 682-687.

Williams, K. D. (2001). Ostracism: The power of silence. New York, NY: Guilford.

Williams, K. D., Cheung, C. K. T., & Choi, W. (2000). CyberOstracism: Effects of being ignored over the Internet. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79, 748-762.

Williams, K. D., & Jarvis, B. (2006). Cyberball: A program for use in research on interpersonal ostracism and acceptance. Behavior Research Methods, 38(1), 174–180. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03192765

Please reference this chapter as:

MacDonald, T. K., Wood, V., & Refling, E. (2019). Social psychology. In M. E. Norris (Ed.), The Canadian Handbook for Careers in Psychological Science. Kingston, ON: eCampus Ontario. Licensed under CC BY NC 4.0. Retrieved from https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/psychologycareers/chapter/social-psychology/