1 An Introduction to Careers in the Psychological Sciences

Meghan E. Norris, Department of Psychology, Queen’s University

Tyson W. Baker, Department of Psychology, Queen’s University

Welcome to Psychological Science

Welcome to the world of psychological science–I’m so thrilled to share the world of psychological science with you. If you are feeling apprehensive about the word “science,” don’t let it throw you off. Although psychology is a science (more on this below!), I want to encourage you to think of science like a power tool: you might be a bit apprehensive at first, but once you learn how to use the tool, things become incredibly exciting. You will get some information on the tool of science in this chapter, with more to come in the chapters to follow.

With our science-power-tool in hand, we can systematically explore, evaluate, understand, and solve questions that we care about. For example, understanding how, when, and why the brain can re-write itself is a) cool, and b) allows us to use this information in contexts such as everyday learning, and recovery from trauma. Science allows us to measure and evaluate efficacy of treatments, including psychotherapy, providing us evidence that a specific treatment is worthwhile and won’t cause harm. Science allows us to understand basic behavioural phenomena like bystander apathy (the tendency for bystanders to not intervene in an emergency), and then it allows us to create interventions based in empirical evidence that will facilitate bystander engagement. Applying scientific methods allows us to create better communications so that people will behave in healthier ways, to design playgrounds to promote active play, to create healthier and more efficient work-places, to develop prevention and harm-reduction programs that work, and to optimize sport performance (just to name a few benefits). By using the scientific method to systematically explore questions like this, we a) can communicate more effectively with our colleagues in other areas by virtue of a common framework, and b) most importantly, have confidence that we are making decisions about how to proceed in any context with the support of empirical evidence.

Notice that there are many contexts in which we can apply psychological science. In this book, we are only going to cover some of the many contexts where psychological science is relevant. Notably, I’m hopeful that future editions will cover more in-depth areas including cognitive psychology, school psychology, the psychology of teaching and learning, and disability management. For now, I’m hopeful this text will provide a strong foundation that we can jump from.

With that, let’s dig in.

What is Psychological Science?

Although the terms psychology and psychological science can be used interchangeably, it is important at this point to re-state that this book approaches psychology as a science. Psychology is the scientific study of brain and behaviour. This means that in the quest to understand brain and behaviour, the scientific method is applied. Thus, those training in the field of psychological science are developing the skills to notice patterns, develop hypotheses, systematically test those hypotheses through measurement, draw conclusions, and use those conclusions to create or refine hypotheses in an ongoing process that continually gives us a more accurate and precise understanding of brain and behaviour. To establish clear boundaries, psychology is not using gut intuition to understand people. Psychology is not making unfounded assumptions. Psychology is not mind reading. Instead, psychology is doing careful background research. Psychology is carefully collecting observations in a systematic way. Psychology is ensuring that observations are collected in an ethical way. Psychology is having strong understanding of research methods and data analytics so as to have the tools to carefully evaluate quality of evidence. Psychology is having awareness of validity, reliability, and generalizability of research findings to appropriately apply research in practice and future research. Psychology is ensuring that ethical responsibilities are met. In this book, we will highlight the ways in which the scientific method has been used to understand brain and behaviour, and we will help you to make important connections between training in the psychological sciences and the many careers that this training prepares you for.

Highlighting the reason this book was created, surprisingly (to us), despite developing skills and knowledge in the science that underlies the wide variety of applications of psychological science, many students do not immediately see the value of their undergraduate degree in psychology when it comes time to employment (Borden & Rajecki, 2000). One goal of this book is to overcome this gap: psychology is an incredibly popular major (e.g., Higher Education Research Institute, 2008), and students who receive training in psychology develop concrete skills and knowledge that employers want. This book was carefully curated to highlight the many ways you can apply your training in psychology to a wide variety of careers. Further, this book was carefully curated to highlight the many ways in which others have applied their training in psychology to solve important questions related to the brain and behaviour. As with any science, we are continually developing and learning. If you are interested in the brain and behaviours, generally speaking, and if you get excited to ask questions, search for answers, and then to apply what you’ve learned, you are in the right place. If you are feeling unsure, that’s okay. Hopefully the following chapters shed new light on the field of psychological science to help you as you develop your long term career goals. If you decide that psychology is not for you, that’s also a win: it’s important that you find an area to work in that meets your personal goals. It’s likely that you will interact with someone who is working from a psychological science framework during your career, and we hope this content gives you a common framework from which to work.

What Do Employers Want

According to a survey of employers conducted by the National Association of Colleges and Employers (2016), the top 10 most highly rated attributes of job candidates were:

- Leadership

- Ability to work in a team

- Communication skills (written)

- Problem-solving skills

- Communication skills (verbal)

- Strong work ethic

- Initiative

- Analytical/quantitative skills

- Flexibility/adaptability

- Technical skills

Although many students might not see how their psychology degree is relevant for the workforce (Borden & Rajecki, 2000), undergraduate training in psychology directly and intentionally addresses at least the first 9 of the top 10 rated attributes desired by employers, and likely all 10. Indeed, the American Psychological Association specifies 5 goals and related learning outcomes for undergraduate programs in psychology which have direct overlap with the above listed attributes that employers seek (American Psychological Association, 2013):

Goal 1: Knowledge Base in Psychology

1.1 Describe key concepts, principles, and overarching themes in psychology

1.2 Develop a working knowledge of psychology’s content domains

1.3 Describe applications of psychology

Goal 2: Scientific Inquiry and Critical Thinking

2.1 Use scientific reasoning to interpret psychological phenomena

2.2 Demonstrate psychology information literacy

2.3 Engage in innovative and integrative thinking and problem solving

2.4 Interpret, design, and conduct basic psychological research

2.5 Incorporate sociocultural factors in scientific inquiry

Goal 3: Ethical and Social Responsibility in a Diverse World

3.1 Apply ethical standards to evaluate psychological science and practice

3.2 Build and enhance interpersonal relationships

3.3 Adopt values that build community at local, national, and global levels

Goal 4: Communication

4.1 Demonstrate effective writing for different purposes

4.2 Exhibit effective presentation skills for different purposes

4.3 Interact effectively with others

Goal 5: Professional Development

5.1 Apply psychological content and skills to career goals

5.2 Exhibit self-efficacy and self-regulation

5.3 Refine project-management skills

5.4 Enhance teamwork capacity

5.5 Develop meaningful professional direction for life after graduation

Thus, there appears to be a gap such that undergraduate students in psychology are failing to see the strong connections between their developing skills, and the attributes desired by the job market.

This book will show you many examples of how you can use your training across a variety of careers, including those outside of “psychology.” To help demonstrate how training in psychology can translate to many careers, it is helpful to start from a common understanding of the foundation of psychological science.

Psychology and the Scientific Method

To belabour the point, psychology is an empirical science. This means that, in addition to theory and logic, most professionals who work in the psychological sciences rely on the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data to inform their work. This is important: we know from research that humans can fall prey to biases including the availability heuristic (the tendency to assume that what comes to mind easily is likely accurate, e.g., Tversky & Kahneman, 1973), false consensus effects (the tendency to assume that our behaviours and opinions are similar with most other people, e.g., Ross, Greene, & House, 1977), and confirmation bias (the tendency to see information which is confirming rather than disconfirming, e.g., Nickerson, 1998). Relying on data (especially data verified by other scientists) to inform our professional opinions helps us to not only limit the effects of these biases, but it also helps us to gain representative insights into phenomenon of interest that are more likely to reflect the true nature of the phenomenon of interest.

As we look with an empirical lens at the brain and behaviours, and as you develop your own professional opinions, you are encouraged to always consider the following 3 concepts when you are considering information presented to you: validity, reliability, and generalizability.

Validity is the degree to which a measure or design accurately captures the construct or process of interest. This means that when you are reading about any finding, you should first ask yourself questions including “are these researchers measuring what they think they are measuring, or did they make a mistake?” “Is this research actually addressing the concept it’s claiming to?”

Reliability is the degree to which a finding consistently appears across time and/or situations. This means that when you are reading about any finding, you should ask yourself questions including “do I think this effect will appear in a similar context if this is done a year from now?” “Do I think there are other variables that might influence whether this effect will appear?” “Do I think there is a better measure of this effect that will more consistently measure this effect?”

Generalizability is the degree to which similar findings are likely to occur in other contexts. This means that when you are reading about any finding, you should ask yourself questions including “do I think that this effect will also appear in other groups of people? If not, why?” “Why should (or shouldn’t) this effect appear in other groups of people?”

A final consideration you should make when engaging with research is critically important: the ethics of the research. You should always ask yourself whether the work you are doing (or learning about) meets the Canadian Psychological Association’s principles for ensuring Dignity of Persons, Responsible Caring, Integrity in Relationships, and Responsibility to Society (Canadian Psychological Association, 2017). You can learn more about this in our chapter on research ethics.

Notice that you have an important role to play here: it is your job as a reader of science to also use your developing skills to ask tough questions of other researchers. Again, even scientists are human, and even with careful work, we can all make mistakes. We need to trust that our colleagues (that now includes you!) will ask tough questions of our studies. From this point on, it is your professional responsibility as a developing psychological scientist to ask questions about validity, reliability, and generalizability if they arise, and also to ask questions about other aspects of research including ethics. You will learn more about asking questions of research in the coming chapters.

Careers in Psychological Science

An undergraduate degree in psychological science is effective preparation for many types of careers. For example, as a result of strong training in the scientific method, students in the psychological sciences are equipped to distinguish causal and non-causal relationships between variables. This means that students can identify if one variable causes another, or if two variables are related but one doesn’t necessarily cause the other (i.e., if variables are correlated). Insights such as these prove valuable in many contexts. For example, when a client presents claiming that Treatment X cured an ailment, a practitioner trained in the psychological sciences should immediately consider the validity, reliability, and generalizability of the claim. Specifically, the treatment may not be valid–perhaps is there a lurking third variable, such as passage of time which often is associated with a reduction in symptoms. To put this into context, Treatment X could cure the cold after 7 days, but most instances of the cold resolve on their own in around 7 days. A student with training in psychological science would design an experiment to test the effects of Treatment X to see whether it is indeed an effective treatment. If we want to make accurate causal claims, then there are proper ways to run the experiments (you will learn more about experimental design in our chapter on research methods). You may have noticed that this example isn’t even psychological in nature. This highlights that psychologists are trained in the scientific method, which can be applied in any area that follows the scientific method.

As overviewed above, students who train in psychological science receive training in both skills and knowledge that are important to employers. Thus, there are many, many career options available to a student who has trained in psychology. Indeed, a challenge that many students in psychology is not “what can I do?,” but rather “how can I choose what to do?

Identifying Possible Pathways

You may find yourself asking one of two questions: what do I want to do, and/or what can I do with training in psychology. Both of these are good questions, and may require different processes to reach satisfying answers. Below is just a brief summary of two search strategies that I often use with students as we explore career opportunities: Broad Search Strategies and Targeted Search Strategies. Broad search strategies best answer the question “what do I want to do,” whereas targeted search strategies addresses “what can I do?”. Note that the below methods are not evidence-based in that I (Meghan) don’t have data to support their use beyond my own personal experience in working with students. Specialists in career development elaborate on career search and development in Chapter 2.

The Broad Search Strategy

This is a strategy for when you have no idea what you want to do, and you are seeking to identify careers that meet your personal interest and long-term development goals. This search strategy uses backwards planning: rather than starting from where you are now and building out, this strategy looks for an end-point and guides you in planning backwards.

Step 1: The Initial Search: Identify 5-10 jobs across organizations that you think look interesting, even if they aren’t jobs that you are qualified for (yet!).

Step 2: Identifying Common Requirements: Do you notice any common requirements among these jobs? If so, this common requirement might be a qualification you consider working towards.

Step 3: Identify Exemplars: Individuals normally change jobs throughout their lifetime. The average length of time that an employee had been with an employer across all US sectors was only 4.2 years (Bureau of Labor and Statistics, 2018). It’s one thing to read a job posting, but it’s another to see the journey to get there. In this step, identify individuals who have jobs that are of interest to you, using tools such as LinkedIn. Are there any early career experiences of desired exemplars that are relevant for you?

Step 4: Planning for the Next Steps: Once you have identified common requirements and typical pathways among your careers of interest, you are in a position to start planning your next steps on your similar pathway. If you have learned that a specific graduate program is required for your careers of interest, it’s time to start searching for graduate programs. Similar to the broad career search steps, identify graduate programs that are of interest to you. What are their requirements? Are there common undergraduate courses that you need for admission? Consider enrolling in those courses now. Are there common volunteer or research assistantship requirements for admission? If so, consider applying for those positions now so that you meet that requirement.

If you are unsure about graduate admission requirements, it is always a good idea to contact your program of interest directly. Requirements and space availability can change year-to-year. Only that specific program has the most up-to-date information on their admissions process.

The Targeted Search Strategy

Sometimes career searches can be much more pragmatic. For example, the desired career might be within a certain geographic location that earns a certain salary.

This Targeted Search Strategy is intended to be a career search strategy, not a job search strategy. That is, if you are asking the question “what should I do with my life in terms of a career?” this may be a helpful strategy. If you are looking for a specific job (i.e., you have your credentials and are actively job searching), you will want to check in with your local career assistance office for guidance.

The Targeted Search Strategy involves going directly to a source and evaluating careers on your criteria of interest. Many resources exist that give specific and concrete information on career specifics. The Government of Canada’s Job Bank (Government of Canada, 2018) is one such resource. This free, online resource provides information on many occupations, the typical educational training paths required for a variety of occupations, average salary by geographic location, and the job availability outlooks associated with many careers. The website uses the National Occupational Classification system (NOC) in classifying jobs. In this classification system, each occupation is assigned a nationally recognized 4-digit code. Similar jobs are typically classified by the same NOC code, although jobs classified together may vary on important dimensions depending on your search goals. The NOC system is helpful to know about, as it may help you to streamline your job search by exploring NOC codes rather than searching for keywords. https://www.jobbank.gc.ca/explorecareers

Although you are encouraged to go to the Government of Canada Job Bank website directly to search for career information (it is updated often!), we have compiled career paths related to Psychology from the Government of Canada Job Bank, and have built an Open Educational Resource with this information. We encourage you to use it as a starting point if you are feeling overwhelmed: Careers Related to Psychology Sourced from The Government of Canada’s Job Bank Resource https://github.com/MeghanNorris/PsychologyCareers

As you look through these careers, we encourage you to think about how the knowledge and skills you are developing in your education can be applied to the careers included. You might find that Activity 1 in the Appendix can help you to make connections between a generic career description and your specific skill and knowledge expertise. For example, as a student with training in psychology, you likely have developed skills related to team work, written and oral communication, data management and analysis, and problem solving.

We want to encourage you to use the Government of Canada Job Bank in multiple ways. For example, not only is the Government of Canada Job Bank a helpful guide for a career search, but it is also helpful for those who are actively applying for jobs. When you receive a job offer, especially for professional careers, there may be an opportunity for negotiations. The Government of Canada Job Bank is an excellent resource for bench-marking average rates of pay, and for bench-marking your credentials in light of a specific occupation. Thus, when asked for your expected salary, you might respond with “Based on data from the Government of Canada, I would like to suggest that my salary would be in the range of $29-$32/hour.” Notice again this tendency to seek data to inform an opinion: your psychology professors repeatedly asking you for evidence develops data-driven skills that will help you in many areas of your life!

In addition to the resources provided above, there are many additional resources available. One that we would like to direct your attention to is hosted by the American Psychological Association, and is quite comprehensive in the information it provides:

Data Tools from the Center for Workforce Studies (American Psychological Association): https://www.apa.org/workforce/data-tools/

Common Professional Skills, Knowledge, and Etiquette Behaviours

There are a number of common skills and professional behaviours that span career opportunities and that either I wish I knew as a student, or that I wish students knew. Note that this section does not highlight professional skills in terms of practicing psychology in a clinical sense, but rather professional skills at a more general level. Specific skills related to sub-disciplines in psychology will be addressed in the chapters to come, and in courses that you choose to pursue.

Searching for Evidence

A background in peer-review

In psychological science, our gold standard for evidence is peer-reviewed scholarly evidence. In the context of empirical research, peer-review is a system where an individual (or team) conducts a study to answer a research question, writes a manuscript describing that study, and then submits the manuscript for “peer-review” at a specific journal chosen by the author(s). The editor of that journal then chooses typically 2-3 experts in the area (reviewers) to read and critique the submitted manuscript. The reviewers provide feedback to the authors and editor, and make recommendations as to whether the paper should be published in that specific journal, revised and resubmitted for further consideration to that specific journal, or rejected from that journal. The editor then goes through the reviewer feedback and makes a decision as to whether the manuscript will be published, and under what conditions if revisions are requested. Very few papers are accepted without any required revisions. If authors choose not to make the requested revisions, of if their paper has been rejected, they are able to submit their manuscript to another journal of their choosing (with or without edits).

The entire research-and-peer-review process can take months, and typically years from start to finish. The feedback from reviewers is intentionally very critical, with the goal of ensuring that rigorous and accurate research is published. Research that does not meet the threshold for rigor and/or accuracy is unlikely to be published in a high calibre peer-reviewed journal. You may have submitted term papers for classes; this is the early training that allows students to gain expertise writing scholarly reports. With enough training and practice, students become experts,and those who choose to can submit manuscripts for publication, become the peers for the peer-review system, and train students of their own.

Academic journals have differing levels of impact—impact is a rough measure of how much people read and cite certain journals. Some journals have a higher readership resulting from a very high calibre of research due to a much higher threshold for publication. For example, some high-threshold journals might require multiple studies that comprehensively test many factors related to a research question to be considered for publication. Other lower-threshold journals might publish research that is interesting but does not yet have a great deal of empirical support. Thus, not all academic journals are considered equal. One proxy of journal quality is their impact factor, usually available on their webpage. Higher impact factors mean greater readership. Note that this is a proxy for quality: high readership does not mean rigorous research. Many tabloid newspapers have high readership, but it doesn’t mean the content is accurate. Highly specialized journals may have fantastic research, but only be read by a handful of specialized researchers because there are only a few experts in the world. Readers must always be thoughtful while they read research, and be actively considering the degree to which the research is valid, reliable, generalizable, and ethical (among other things, but these 4 are a great start!). This is fundamental to what reviewers and good researchers do.

Where to find peer-reviewed articles

Members of the public typically have to pay to read scholarly research, including peer-reviewed research (but, see Changes Happening in Peer-Reviewed Research section below). If you are currently a member of a university community, you likely have access to scholarly research through your library. Universities pay sometimes millions of dollars to have access to academic journals (e.g., Bergstrom, Courant, McAfee, & Williams, 2014). You are able to go into your campus library to access scholarly research, or, if you are accessing the internet from campus or have access to a proxy-server, you can typically go to a website like http://www.scholar.google.com and be able to access the journals your institution is subscribed to. If you type in keywords, similar to a regular Google search, the Google Scholar search engine will populate with scholarly articles. Again, remember that this doesn’t mean they are quality search hits, but they will be scholarly in nature. You should always be asking yourself “to what degree is this research valid, reliable, generalizable, and ethical?”

If you have a more targeted literature search, you might use a targeted search engine such as PsycInfo which searches Psychology resources. To determine the best targeted search engine, you might use a database identification tool through your library. Here is one example of a database identification tool from Queen’s University: https://library.queensu.ca/search/databases/browse/all

If you are struggling with finding scholarly research relevant for your question of interest, librarians are trained in conducting literature searches. Their services are typically free for you to access, and you can find librarians in libraries both at educational campuses, as well as in public libraries. When conducing any type of literature search, you would be wise to consult with a librarian.

Changes Happening in Peer-Reviewed Research

For many good reasons, changes are happening to the process of publishing research in psychological science. Although this will be reviewed in more detail in the Research Methods chapter of this book, there are a few important changes happening that you should know in the context of reading and interpreting psychological research for your professional development.

The process of peer-review described above continues to mostly hold true. However, recently pre-registration has been added to the process. Pre-registration is submitting the research question(s), and basic research design plan before the research is conducted. That is, the research plan is registered prior to conducting the research itself.

In some cases, this pre-registered plan is peer-reviewed and researchers get feedback about potential flaws in design before conducting the study. This use of the pre-registration process has great merit in the facilitation of getting constructive criticism early in the process at a time when it can be used to tweak research design. Imagine if your professor gave your term paper feedback before you submitted it. Would that result in a stronger final paper?

In other cases, the pre-registration details are kept temporarily private, to become public once the research is complete to ensure that researchers are conducting the research consistent with their pre-registered intentions. This is intended to minimize researcher bias (intentional or unintentional) during the research process.

Another change happening in the world of scholarly publications is a trend towards open-access publishing. Open-access publishing is publishing in such a way that readers do not need to pay a fee to access the work. As noted above, accessing scholarly research can be expensive and prohibitive. Some academic journals, and some textbooks (this one, as an example!), have been written intentionally to be open-access. In addition to pragmatics regarding how to make the open-access system sustainable (e.g., who pays for server maintenance, etc), one downside is that typically open-access resources are viewed as having less prestige than those publications that require payment to access and, as a result, authors do not often consider them as a primary destination for research publication. It seems that a shift is now underway, though. Some open-access journals, including PLOS ONE (2019), employ a peer-review system and have grown in credibility. As scholarly research becomes more available to the public (which personally, we think is an excellent improvement), it is critical that the public has the tools to critically read and evaluate this research. Again, always be asking the degree to which research findings are valid, reliable, generalizable, and ethical (there are other things to consider, but this is a good first cut!).

Business Etiquette

As with many professional contexts, there are professional situations that you are likely to find yourself in while working in a variety of different career trajectories, and there are some common business etiquette behaviours. These behaviours often are taught from mentors, are rarely explicitly addressed, and may or may not actually be best practices.

To help ensure that you have awareness of these types of professional etiquette behaviours, some are addressed below. Please read these with thoughtful caution, however. Etiquette can change within a professional body (and oftentimes ought to change), and often varies significantly across professional bodies. To give an example, in some professional contexts it is perfectly appropriate to wear jeans and sneakers to a job interview. In others, a full suit is expected. If you are ever in doubt about appropriate professional etiquette, ask a trusted mentor. If you don’t have a trusted mentor, ask any friendly professor for some advice. They may be able to steer you in the right direction. If you don’t have any friendly professors, drop Meghan (editor of this book) an email and I will do my best to connect you with a helpful resource that is close to you.

Some common business etiquette behaviours within psychological science are highlighted next that will span many career trajectories, but again recognize that this can vary by region, institution, and individual. Appropriate etiquette can change over time, and it may be different within subsets of the population. If you are unsure of business etiquette (or if you want to work to change it), please connect with a trusted advisor.

Addressing Professors

Many students coming into university from high school will address their professors as “Mr./Ms. Lastname.” In a higher-education setting, professional titles should be used. In the context of a North American university, instructors should professionally be referred to as “Dr. Lastname” if they have a doctorate, or “Prof. Lastname” if they do not. This is not true in other systems including the UK. In those systems, “Prof. Lastname” is used only for those professors who have achieved full professorship. Note, female instructors should never be referred to as “Miss” or “Mrs.,” unless specifically requested. These titles are used to indicate a woman’s marital status which is irrelevant to her professional status. Relatedly, as we learn more about the impacts of pro-nouns, gendered titles used to address individuals may change.

In the event that you are unsure of how to address someone in their preferred way, for example if you are unsure of whether a gendered title is appropriate, or whether you should refer to someone by first name, there are appropriate ways to find out. In some cases, an individual will be explicit in telling you how they preferred to be addressed. In other cases, you might ask. For example, you might ask for permission to use someone’s first name if you have a close collegial working relationship with them. An example of how to ask a question like this is: “Dear Dr. Lastname, I want to ensure that I am addressing you appropriately. What is your preferred way to be addressed?”

Please note that if a professor, or any professional, prefers to be called by their professional title, this is perfectly appropriate: they are working in their professional setting and are requesting to be called by their professional title. Let’s consider this in another context: A police officer might be called Officer Jeffrey. It would be out of context to call Officer Jeffrey “Mrs. Jeffrey” if Officer Jeffrey was in uniform. Likewise, it would be up to Officer Jeffrey if she was willing for someone to call her “Sue” when she was on duty. Officer Jeffrey might be comfortable with her partner calling her Sue, but not a member of the public that she is serving. Notice that there is a great deal of context in this example, just as there is in any interpersonal dynamic. If you are unsure of how to address your instructor, or any colleague, a friendly email asking for their preferred way to be addressed is appropriate.

In a professional context, for example at a lecture, you should likely default to referring to any colleague by professional title even if you have permission to use their first name. For example, I introduce some of my best friends as “Dr. Lastname” in professional contexts.

Writing An Email

We all have questions, and an email is a common way to ask those questions to professors and other professionals. Before sending an email to anyone, it is helpful to first ask yourself a couple of questions.

- What exactly is it that I need help with?

- What are the best resources for me to get the needed help? For example, if you are looking for deadline or absence policies, before sending an email you should first check the syllabus of the course you are in (if in the context of a class), any previous correspondence (do an email search), and relevant webpages. Some organizations, including universities, also have discussion boards in their online platforms for certain types of questions. If you have exhausted your resources and are needing some extra support from an instructor or a boss, an email may be very appropriate.

It may be tempting to send an email to an employer or instructor similar to the way you would send a text, especially if you have a quick question. Although this may be appropriate if you know someone well and are engaged in an email conversation (as we often do outside of professional contexts), text-style email is not typically an appropriate method for professional communication. When emailing in a professional context, you want to ensure the following information is included:

- a proper salutation

- who you are, and the context you are writing about

- a concise statement of your question/comment, overviewing what you’ve already done to try to solve the problem or answer the question

- your full name and contact information, including your student number if relevant

Two sample email templates are below, although you should edit them prior to use so that your own professional tone comes through:

Dear [Ms. CEO],

I am a new employee in your marketing department, and am writing to ask for clarification about [Project X]. Specifically, I’ve [read through the request for proposal and have done research on our competitors], but am unable to find information on [sales history]. My goal is to [create a thorough document that has all relevant information to ensure our success]. Could you please direct me towards more information?

Thanks for your time!

With kind regards,

Full name

Email address/phone number

Dear [Dr. Lastname],

I am a student in your [course name, and section]. I am writing to ask for [clarification on, further information regarding, etc]. Specifically [give summary of the background research you’ve already done e.g., consulted the syllabus], and my current understanding is [summary]. I am seeking clarification about [specification of what is not understood]. Could you please provide me more information to help me better understand?

Thanks for your time!

With kind regards,

Full Name

Student Number 0123456789

When using electronic communication, please remember that USING ALL CAPLOCKS IS CONSIDERED YELLING. Excessive use of exclamation points can also be interpreted as yelling!!! The way in which you type communicates tone. If sending an important email, you might ask a friend or colleague to first read it over to ensure that the tone you are using is appropriate for the context. If an email reads more harshly than intended, you might soften it by adding an emoji (if professionally appropriate—there are boundaries on appropriate use of emojis), or by acknowledging in text to the reader that the email reads more harshly than you intend it to.

Leaving a voicemail

Sometimes an uncomfortable task, you will undoubtedly have to leave a voicemail at some point during your professional career. When leaving a voicemail, we recommend that you speak slowly, ensure that you give your name and a way to contact you for follow up. Importantly, give this information twice! Sometimes there is a crack in the phone line and a digit can’t be heard. Leaving your name and contact information twice helps to ensure that your recipient gets all of the information they need to follow-up with you.

Asking for letters of reference/experience

Students are sometimes uneasy asking for letters of reference. Please know that each year, most instructors get dozens of requests for letters of reference. I tell you this a.) to reassure you that you are engaging in an expected professional behaviour by asking for a letter of reference and b.) to help you understand what an effective request for a letter of reference contains.

Instructors often teach dozens, and sometimes hundreds, of students in a given year. Instructors also often teach multiple courses in a given academic year. As a result, although you may have a great relationship with your instructor, and they know you well, they may have forgotten some important details related to your professional interactions that could be helpful in a letter. Below is the information that I (Meghan) request, in addition to an unofficial transcript, when students ask for a letter of recommendation, along with my internal reasoning for asking the question. Your letter-writers may request different information. Please consider this as a starting place, and use the format provided by your letter-writer when requested:

General information to help set the context:

- The nature of the programs you are applying to

A letter of reference for a specific job might be very different than application to graduate school in psychology, which might be different from an application to another type of program. Please give a brief overview of the program so that the letter can be framed appropriately.

2. An overview of the submission process

Graduate school letters of reference are often submitted confidentially through an online portal. Not all letters go through this process, and job letters can vary significantly in their submission process. Please give a brief overview of how the process will work, and whether letters should be directly addressed to a specific recipient (e.g., Dear Graduate Committee, vs “Dear Ms. CEO”). Because reference letters have to be submitted in very specific ways, it’s easiest to give these details right away either in an attached file or link to a webpage. Be sure to include the deadline in your request, and give your referee at least two weeks before the deadline.

Specific information to help write a strong letter:

- Full name on record, preferred name and pronouns, and student number

Sometimes students have different preferred names from those on record, and I want to make sure that those receiving the letter know who I am referring to. Having access to all names, preferred pronouns, and the student number also helps letter writers to search records more effectively so that they can write a comprehensive letter.

- All courses taken with me as instructor (including the year taken), the components of those courses, and your overall grades

Sometimes courses change slightly across years, and the components of the course can also change. Specifying the components in a course may help your letter writer to write a stronger letter—for example, if there was a teamwork component, they can speak to this. Remember that there are dozens of students in multiple courses asking for letters: by providing this information in your request, you are making it much easier for your letter writer, and you are demonstrating conscientious professional behaviours. Thus, this also helps your letter writer when they comment on your professional skills!

- Academic Achievements (e.g., Honours List, any other academic awards, conference presentations, any publications if relevant)

Instructors often don’t get notice of your individual achievements, and are excited to hear about them. By letting your letter writer know about these achievements, they can include information about them in your letter. Even if your letter writer knows about the achievement, a reminder is helpful.

- Volunteer and work experience (both academic and non-academic)

In this section, include any volunteer or work experience that might be relevant for the letter. Even if you volunteer in the lab of your letter writer, please include this. It helps to know that you’ve provided a comprehensive record.

- Non-academic Achievements

Have you done something great that isn’t related to your academics? This is important and matters! Please be sure to tell us a bit about it.

Etiquette at a Conference

Depending on your area, appropriate business behaviours can vary. For example, some conferences are very formal and require full business suits, whereas others are more business-casual in nature. If you have the opportunity and resources to attend a conference, it is appropriate to ask a trusted advisor about the level of formality at the conference, including dress code. Some conferences have pictures on their website of previous conferences, so you can see typical conference attire for yourself. If the dress code is not obvious, you might ask your advisor, or even the organizer of the conference, “Is there a dress-code at the conference?” Below, additional business etiquette considerations are overviewed that are fairly common across contexts. We didn’t learn many of these behaviours until after we graduated with PhDs, and wish we knew some of them earlier!

Nametags

Nametags should be worn on your right side. The logic is when you shake hands (with your right hand), your colleague’s eyes can follow a relatively straight and natural path from your shaking hand to your visible nametag while also comfortably make eye contact.

Your left side is where you would wear a pin, if relevant. The pin would thus be “over your heart.”

The Elevator Pitch

Elevators used to be where all important people met. Okay, that’s not true, but the term “The Elevator Pitch” refers to a description of your expertise that you can communicate to someone in a few seconds (the length of an elevator ride). It’s the ultimate tl;dr (too long; didn’t read) of your expertise.

It is worth your time to develop and practice an elevator pitch of your interests now. This pitch can and will change with time, but you will be interacting with professors and potential colleagues throughout your training. An elevator pitch should be maximum 60 seconds in length and summarize your professional interests and experiences. For example, you might use the following structure:

“I am a [undergraduate student/research assistant/graduate student] at [institution] and I am interested in [general summary of area of interest].”

Notice that this is a very general and short professional summary about yourself. If the person you are speaking with is interested to learn more, they are able to ask follow up questions. They can also comfortably “get off of the elevator at their floor” (i.e., discontinue the conversation) if unavailable for further follow-up.

The Dinner Table

So many glasses, plates, and cutlery. Whose is whose, and when should you use what?

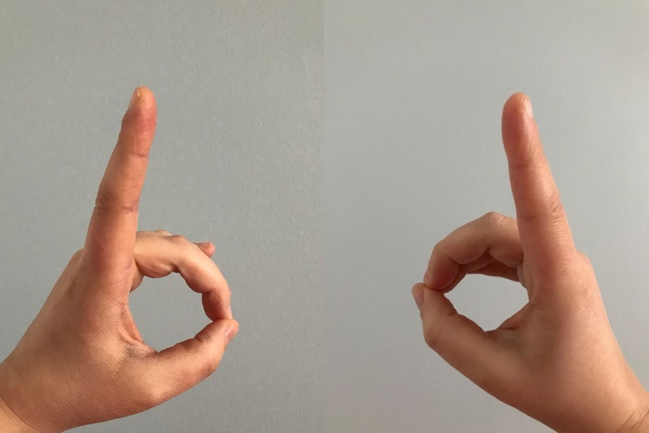

Drinking glasses and bread plates: drinking glasses are to your right, and your bread plate (small plate) is to your left. Here is a handy trick to help you remember:

The “b” is your bread side (left), and the “d” is your drink side (right).

Forks: start farthest away from your plate, and work your way inwards with each course.

Food and Networking

Practice holding food and drink in your left hand during networking events so that your right hand is free for shaking hands. Passing your food or drink to your left hand just isn’t as smooth, especially if you have crumbs or condensation on your hand. You don’t want to give a crummy handshake.

The Handshake

Handshakes can be awkward, especially if you haven’t practiced handshakes. It takes practice to have a firm-but-not-painful handshake. It also takes practice to kindly decline a handshake if you are uncomfortable or unable to shake a hand. It also takes practice to adjust if your handshake is declined (it is not necessarily a social rejection if a handshake is denied—many invisible conditions prevent handshaking). It also takes practice in shaking hands with someone who has a visible disability if you are unsure how to proceed. Notice that “practice” is repeated here. Your first few professional handshakes might be awkward, and that’s to be expected. If the thought of giving handshakes makes you nervous, it is worthwhile to reach out to a trusted mentor or career centre for guidance. For more insights specifically on handshake behaviours with individuals who have a visible disability, please see (https://styleforsuccess.com/blog/how-to-shake-hands-with-someone-with-a-disability/). As with all interpersonal interactions, be aware that contexts can vary. Never touch someone who gives indicators that they do not want to be touched (e.g., the person steps away from you, and/or has closed body language). If you are unsure, a friendly verbal greeting is more appropriate than potentially violating someone.

The Art of Thank You

In your career you will encounter many people who will go out of their way to help you either in small or large ways. Although not expected, it can strengthen an interpersonal relationship to send a genuine thank you to a person who has helped you in a meaningful way. You can of course send an email of thanks, but in situations where someone has significantly made the world a better place for you, sending a simple hand-written thank-you card is often much appreciated. Indeed, we often underestimate how good receiving a thank you can feel for our recipients (e.g., Kumar & Eply, 2018).

Are there other areas of professional knowledge and behaviours that you are unsure about? If so, in addition to following up with a trusted mentor or career development office, please feel free to send Meghan (the editor of this book) an email. We may include your question in a future edition of this book!

How to Use This Book

Building on themes highlighted in this introduction, this book has been created to provide you with content on applications of psychological science and careers in psychological science written by experts across Canada. These experts were once where you are: students in a psyc course. Their chapters will vary somewhat in format to allow each sub-discipline’s “voice” to come through, but all chapters have an intentional focus on both research and application of psychological science, in addition to content regarding educational training paths and career options.

We hope that this book highlights the many careers available to students who train in the psychological sciences. We hope this book also provides you with new insights into the many ways in which psychological sciences addresses important questions, and ultimately influences the world around us in its application. As with anything you read, I encourage you to always be considering questions related to validity, reliability, generalizability, and ethics as you read this book. Indeed, this is how new research questions are often generated! In that spirit, in case no one has done this already, I welcome you as a colleague in the psychological sciences, and look forward to learning about your future work.

Activity 1: Identifying your skills

Norris & Baker, 2019

Below you will find the top 10 most highly rated attributes on behalf of employers (National Association of Colleges and Employers, 2016). For each attribute, reflect on your experiences and see whether you can identify a specific example of how you have displayed or developed that attribute. For example, if in a course you had a team-based project that you scored highly on, you should include that in your chart under the “ability to work in a team” section. Have you taken a course that has required you to use software to analyze or manage data? That can go under the “technical skills” section.

You likely won’t have an example for every box, and that’s okay! The goal is to identify some specific examples so that you can rely on these to demonstrate strong attributes.

|

|

Coursework that demonstrates my skills and ability | Volunteer experience that demonstrates my skills and ability | Paid work experience that demonstrates my skills and ability | Awards/honours that demonstrate my skills and ability |

| Leadership |

|

|||

| Ability to work in a team | ||||

| Communication skills (written) | ||||

| Problem-solving skills | ||||

| Communication skills (verbal) | ||||

| Strong work ethic | ||||

| Initiative |

|

|||

| Analytical/quantitative skills | ||||

| Flexibility/adaptability | ||||

| Technical skills |

|

References

American Psychological Association (n.d.). Data Tools from the Center for Workforce Studies. Retrieved from American Psychological Association website: https://www.apa.org/workforce/data-tools/

American Psychological Association (2013). APA guidelines for the undergraduate psychology major version 2.0. Retrieved from American Psychological Association website: https://www.apa.org/ed/precollege/about/psymajor-guidelines.pdf

Bergstrom, T. C., Courant, P. N., McAfee, R. P., & Williams, M. A. (2014). Evaluating big deal journal bundles. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(26), 9425-9430.

Borden, V. M., & Rajecki, D. W. (2000). First-year employment outcomes of psychology baccalaureates: Relatedness, preparedness, and prospects. Teaching of Psychology, 27(3), 164-168.

Bureau of Labor and Statistics (2018). Employee tenure summary. Retrieved from Bureau of Labor and Statistics website: https://www.bls.gov/news.release/tenure.nr0.htm

Canadian Psychological Association (2017). Canadian code of ethics for psychologists (4th ed.). Retrieved from Canadian Psychological Association website: https://cpa.ca/docs/File/Ethics/CPA_Code_2017_4thEd.pdf

Fuchs, E., & Flügge, G. (2014) Adult neuroplasticity: More than 40 years of research. Neural Plasticity, 2014, 1-10. doi:10.1155/2014/541870

Goldstein, N. J., Cialdini, R. B., & Griskevicius, V. (2008). A room with a viewpoint: Using social norms to motivate environmental conservation in hotels. Journal of Consumer Research, 35(3), 472-482.

Google LLC (2019) Google Scholar [Search engine]. Retrieved from https://scholar.google.ca/

Government of Canada (2018). Labour market information. Retrieved from Government of Canada website: https://www.jobbank.gc.ca/explorecareers

Higher Education Research Institute. (2008). 2008 CIRP freshman survey. Retrieved from Higher Education Research Institute website: http://www.heri.ucla.edu

Hundley, J., Elliott, K., & Therrien, Z.(2013). The efficacy and effectiveness of psychological treatments. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Psychological Association. Retrieved from https://www.cpa.ca/docs/File/Practice/TheEfficacyAndEffectivenessOfPsychologicalTreatments_web.pdf

Kerr, T., MacPherson, D., & Wood, E. (2008). Establishing North America’s first safer injection facility: lessons from the Vancouver experience. In A. Stevens (Ed.) Crossing frontiers: International developments in the treatment of drug dependence. Brighton, UK: Pavilion Publishing.

Kumar, A., & Epley, N. (2018). Undervaluing gratitude: Expressers misunderstand the consequences of showing appreciation. Psychological Science, 29(9), 1423-1435.

Linda Fitzpatrick (2018, February 24) How to shake hands with someone with a disability [Web log post]. Retrieved from https://styleforsuccess.com/blog/how-to-shake-hands-with-someone-with-a-disability/

Lindsay, R. C., Ross, D. F., Read, J. D., & Toglia, M. (Eds) (2007). Handbook of eyewitness psychology: Memory for people. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum and Associates.

National Association of Colleges and Employers (2016). Job Outlook 2016. Retrieved from National Association of Colleges and Employers website: http://www.naceweb.org/career-development/trends-and-predictions/job-outlook-2016-attributes-employers-want-to-see-on-new-college-graduates-resumes/

Nickerson, R. S. (1998). Confirmation bias: A ubiquitous phenomenon in many guises. Review of General Psychology, 2(2), 175.

PLOS ONE (2019). Benefits of open access journals [Webpage]. Retrieved from https://www.plos.org/open-access

Polanin, J. R., Espelage, D. L., & Pigott, T. D. (2012). A meta-analysis of school-based bullying prevention programs’ effects on bystander intervention behavior. School Psychology Review, 41(1), 47-65. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Dorothy_Espelage/publication/235220413_A_Meta-Analysis_of_School-Based_Bullying_Prevention_Programs’_Effects_on_Bystander_Intervention_Behavior/links/00b4952c602de18785000000.pdf

Ross, L., Greene, D., & House, P. (1977). The “false consensus effect”: An egocentric bias in social perception and attribution processes. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 13(3), 279–301. doi:10.1016/0022-1031(77)90049-X

Shirazipour, C. H., Evans, M. B., Caddick, N., Smith, B., Aiken, A. B., Martin Ginis, K. A., & Latimer-Cheung, A. E. (2017). Quality participation experiences in the physical activity domain: Perspectives of veterans with a physical disability. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 29, 40-50. doi:10.1016/j.psychsport.2016.11.007

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1973). Availability: A heuristic for judging frequency and probability. Cognitive Psychology, 5(2), 207-232.

Please reference this chapter as

Norris, M. E. & Baker, T. W. (2019). An introduction to careers in the psychological sciences. In M. E. Norris (Ed.), The Canadian Handbook for Careers in Psychological Science. Kingston, ON: eCampus Ontario. Licensed under CC BY NC 4.0. Retrieved from https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/psychologycareers/chapter/introduction/