8 Developmental Psychology

Valerie A. Kuhlmeier, Department of Psychology, Queen’s University

Kyla Mayne, Department of Psychology, Queen’s University

Wendy Craig, Department of Psychology, Queen’s University

-

WHAT IS DEVELOPMENTAL PSYCHOLOGY?

As a human progresses through life, they transition from a zygote to a crying infant, from a babbling toddler to a curious kindergartner, from a quick-learning grade school student to a broody adolescent, from an independence-seeking emerging adult to a mature adult, and later, to an elderly senior. Across the lifespan, there are numerous physical, cognitive, and social changes. The field of developmental psychology is focused on observing these changes and elucidating their underlying mechanisms.

People with training in developmental psychology have learned how to be scientists. Like all scientists, they know the key theories of their field, and importantly, they recognize how those theories came to be. They can create empirical research methodologies to test new hypotheses, and they analyze the resulting data. They know how to critically evaluate claims and effectively communicate findings to other scientists as well as the broader community. Depending on their chosen career and level of education, people trained in developmental psychology may apply some or all of these skills in their work.

The specific area of interest for any one developmental psychologist may differ greatly from the interests of other developmental psychologists. It is arguably the most interdisciplinary of the traditional areas of psychology, as individuals may focus on development in relation to sensation and perception, cognition, reasoning and behaving in the social environment, personality, and brain systems. Within these topics, developmental psychologists may focus on what we think of as normative development, as well as atypical development.

Because of this diversity, the questions that developmental psychologists ask can seem disconnected from each other. Take a look at a typical introductory textbook on the topic, and you will likely see research questions as wide-ranging as: When do infants perceive physical depth? How do children learn the meanings of words? How does moral reasoning change from early to later childhood? Is the development of theory of mind in humans different from that of other species? How do bullying experiences in childhood affect later victimization in adulthood? How do cultures differ in pedagogical practices? What is the role of parents in the development of emotion regulation? How does gender identity develop?

The thread that connects these diverse topics, though, is the approach that developmental psychologists take. There is a shared interest in understanding the mechanisms of change by examining the interactions between nature (our genetic inheritance) and nurture (the physical and social environment). Within this framework, species-typical developmental paths can be observed, but intriguing individual differences may also be uncovered.

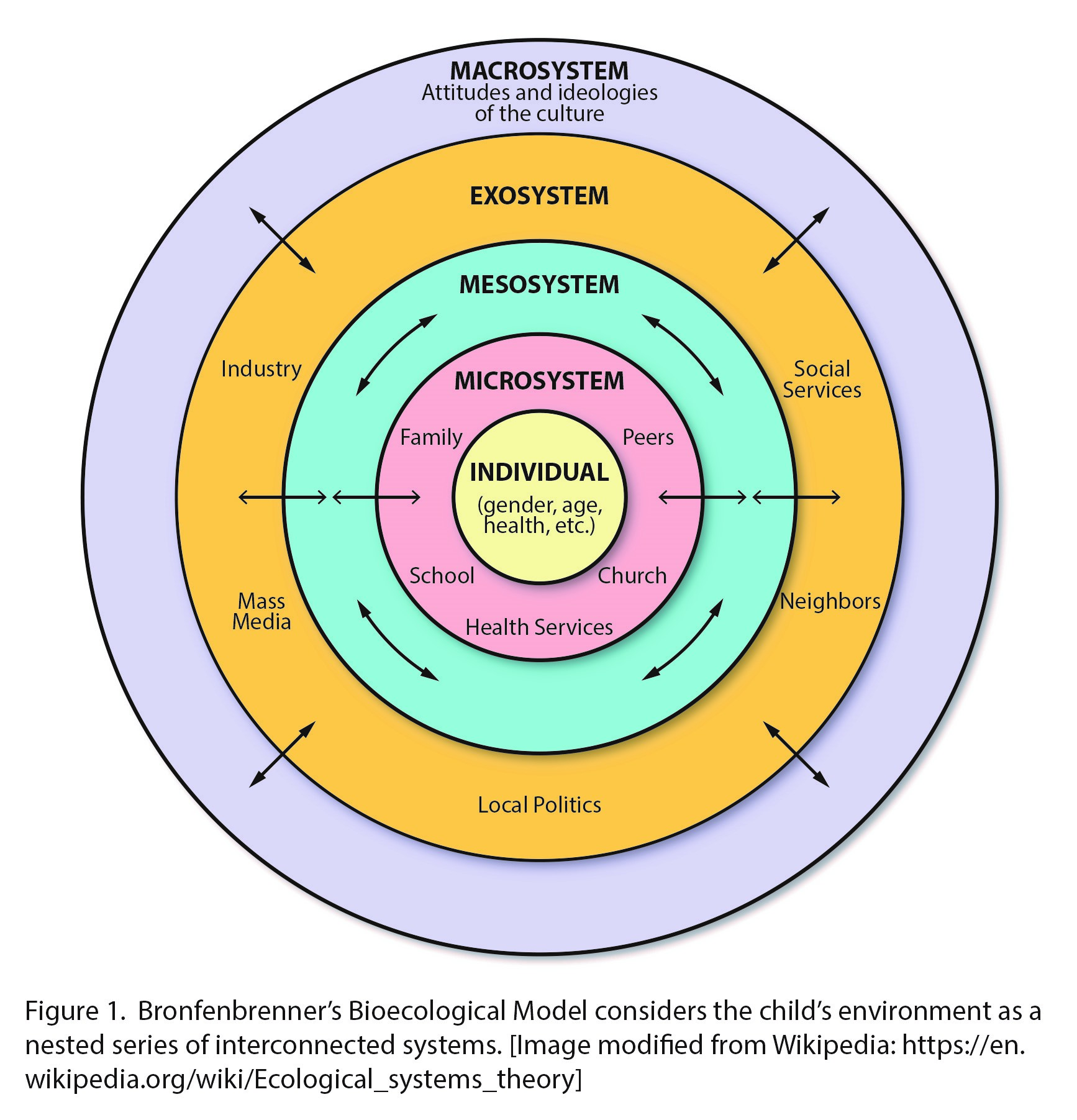

Perhaps one of the best ways to picture the general context of development is by considering Urie Bronfenbrenner’s seminal Bioecological Model (Bronfenbrenner, 1979; Figure 1). This model considers the multi-directional impact of environmental factors on a child’s physical, social, emotional, and cognitive development. In the model, there are a series of nested systems, with the child (including his or her particular combination of genes, temperament, age, health, physical appearance, etc.) at the center. The systems interconnect, and themselves exist within the ‘chronosystem’, which considers circumstances that change over time.

When you consider this complexity, as well as the various domains of development that psychologists examine, it may not be surprising that the methods used by developmental psychologists who are actively involved in research are quite varied. Some methods share commonalities with other areas of psychology: surveys, naturalistic or structured behavior observation, verbal interviews, genetic assays, and neuroimaging with fMRI and electroencephalography, among others. A primary consideration within developmental research, though, is the age-appropriateness of the methods. This is particularly evident when testing infants who are not yet speaking and have limited motor ability, but applies to all ages to some extent.

Another consideration is how development is to be examined. For example, does the research question pertain to whether an ability is present at a certain age? If so, researchers might focus on one time point (e.g., 5 months of age). Alternatively, is a comparison to be made between certain ages? In this case, researchers may use a cross-sectional approach, comparing different groups of children of different ages, or they might create a longitudinal design in which they follow the same children over a period of months or years. Yet another approach is the microgenetic design, in which researchers attempt to gain an in-depth understanding of the mechanisms of change. In a microgenetic design, the focus is on children who are thought to be on the cusp of a particular change, and researchers make observations during a number of sessions over a short period of time.

SECTION RECAP

People trained in developmental psychology have learned the historic and current theories of developmental science and have a critical understanding of how to conduct and interpret research. One individual’s specific focus may differ greatly from another’s (e.g., the development of numerical understanding versus gender development), but they will share a common interest in uncovering the mechanisms of change. In turn, these mechanisms are considered within the complex interactions between nature and nurture.

In the last section of this chapter, some of the many careers and educational paths related to developmental psychology are presented. Before getting there, though, you will see examples of research and how it has been (and continues to be) extended and applied. These sections are divided into two areas of developmental research: social and cognitive. The lines separating the areas may at times seem ‘fuzzy’; for example, a researcher interested in the development of a cognitive process will likely consider the role of the child’s social experience (e.g., how is information being presented to the child by others?). Yet, the divisions provide an organizational scheme for presenting important themes and research methods within the larger field of developmental psychology.

-

SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT

The earliest social experiences for humans occur soon after birth, often with the immediate family. In typical development, for example, newborns show a marked attention to faces and soon are able to recognize the individual faces of those around them (e.g., Bartrip, Morton, & de Schonen, 2001). This early interest in people is thought to start us on a developmental path toward the complex sociality that characterizes our species.

This section will begin by considering what developmental psychologists have discovered about social experiences during infancy and early childhood. Focus will then turn to the development of social relationships, including the child’s own social identity. Throughout, examples will be presented of how this knowledge has been extended and applied. The topics and examples are, of course, limited, but the aim is to present major themes and directions.

EARLY SOCIAL EXPERIENCES

Our species has a relatively long period of vulnerability; we are born helpless and unable to survive without a caregiver. To ensure infants’ survival, and by extension, the survival of the species, infants and caretakers have developed a complex system of behaviours that fosters a strong relationship and motivates adequate caregiving (Simpson & Belsky, 2008).

It was relatively recently, though, that we started to have a more complete understanding of the necessary features of human caregiving. Observations of children who were separated from their parents during World War II showed that these children were emotionally disturbed, even those who were in institutions that provided good physical care (e.g., Bowlby, 1953). What appeared to be missing, it was argued, was the opportunity to create socio-emotional bonds with caregivers. Relatedly, research by Harry Harlow in the 1950s demonstrated that infant rhesus macaque monkeys preferred to spend time in contact with a cloth-covered apparatus than a metal wire apparatus, even though the latter provided milk. In fact, the infant monkeys with access to a ‘cloth mother’ showed more species-typical behaviour, exploring the world and then returning to the soft apparatus as if it were a secure base.

Together, these findings formed the initial basis of Mary Ainsworth and John Bowlby’s attachment theory. The ideas were expanded through studies suggesting that infants’ early experiences with primary caregivers shape their social and emotional development. Through the interactions with a sensitive caregiver, infants form a ‘working model of attachment’, a mental representation or schema of positive social relationships. Without these early experiences — or with experience with an insensitive caregiver – children’s social development can be compromised (Please see Box 1 for more on this topic).

Since this initial research, developmental psychologists have continued to expand our understanding of the significance of early social experiences. For example, there is evidence for both cultural universals and cultural variations: though the importance of attachment security appears to be universal, securely attached children in different cultures may differ in how often they are in close physical proximity to their mothers (e.g., Posada et al., 2013). Additionally, the research in this area has provided us with a foundation for creating interventions to improve parent-child interactions. Developmental psychologists work with clinical psychologists and health care professionals to design and evaluate programs that focus on sensitive parenting behaviour. As one example, nursing professionals at Toronto Public Health in Ontario, Canada, joined with clinical and developmental psychologists to elaborate and evaluate the ‘Make the Connection’ parenting program. When compared to a control group, this program was found to increase sensitive caregiving behaviour and improve parental attitude in at-risk mothers through in-class activities that included reflective discussion while watching video of their interactions with their infants (O’Neill, Swigger, & Kuhlmeier, 2018).

Developmental psychologists have further applied the research on early social experiences to questions about the impact of nonparental childcare. For many families, parents hold jobs by necessity or choice, and children may spend time with other caregivers. A large-scale study in the U.S.A., as well as other smaller-scale studies, suggested that when childcare is high quality (e.g., low turnover of caregivers and a low number of children per caregiver), children can still form secure attachments with their mothers when their mothers show sensitivity in their time together. Further, high-quality childcare can even compensate when children experience unresponsive parenting from their mothers (e.g., NICHD Early Childcare Network, 1997).

BOX 1. ROMANIAN ADOPTION STUDIES

As you have just read, throughout the 1900s developmental psychologists increased our understanding of the role of sensitive caregiving in early social development. It may come as a surprise, then, to learn that as late as the 1980s and 1990s, many children in Romania lived in institutions with relatively little contact with caregivers, as demanded by the political dictatorship at the time.

When the political power shifted, children were adopted by families in different countries. Across a series of studies, the development of these children was examined, often in comparison with both Romanian and non-Romanian children who had been adopted early in infancy (e.g., Nelson et al., 2007; Rutter, O’Connor, & The English and Romanian Adoptees (ERA) Study Team, 2004). The studies found that Romanian children who were adopted at an older age (e.g., 12 to 24 months and 24 to 42 months) often showed atypical physical, social, and cognitive development as compared to children who had been adopted at a younger age, even after years of living in a loving and supportive environment.

These findings were important for the information they provided on the significance of early social experiences in human development and for the implications for public policy (Rutter et al., 2009). Also notable, though, was the consideration of the ethics of the research, with consideration of the potential for exploitation, the risk/benefit ratio, and cultural sensitivity (Zeanah et al., 2006).

DEVELOPMENT OF THE SELF

It may seem strange to read about the development of ‘the self’ in a section on social development. Yet, one’s self-concept develops through interactions among all the systems in Bronfenbrenner’s model (refer back to Figure 1), including, importantly, our interactions with others.

Early in development, an emerging sense of self can be seen when infants recognize that they have agency and are able to control their environment (to some extent!). For example, at 2 to 4 months of age, infants show excitement when they can cause a mobile to move via a string attached to their kicking foot (e.g., Rovee-Collier, 1999). In the toddler years, children come to realize that when looking in the mirror, they are looking at an image of themselves. The sense of self continues to become more elaborate during the preschool years, and 3 to 4 year olds will describe themselves in terms of their physical features (I have brown hair) as well as their social relationships (I have a brother). During the elementary school years, children increasingly engage in social comparison (Other kids at school do better in math; e.g., Harter, 1999), and in adolescence, the importance of social acceptance by peers is strong (e.g., Damon & Hart, 1988).

Developmental psychologists now have amassed a rich body of research on the development of the self, including focus on topics such as ethnic, sexual, and gender identity. In many cases, the research aims to be cross-cultural, as identity formation is influenced by the opportunities children and adolescents have, which are, in turn, impacted by economic and historical status, among other factors. The research is continually being applied with the aim of improving health and well-being (see Box 2 for an example in relation to gender identity).

Focus has also turned to one particular element of self concept: self esteem. How we evaluate ourselves is related to life satisfaction, and low self esteem in childhood and adolescence is associated with negative outcomes such as substance abuse, depression, and withdrawal from social interactions (e.g., Donnellan, Trzesnieswski, Robins, Moffitt, & Caspi, 2005). Receiving praise can typically help to increase self esteem, but developmental psychologists have suggested that inflated praise (You are the best at drawing!) can actually have detrimental effects for children with low self esteem. In one study, children who were visiting a museum drew a picture and were told that it would be evaluated by a painter (there was no actual painter, only the experimenters). Some children received inflated praise (You made an incredibly beautiful drawing!), while others received either no praise or non-inflated praise. Children with low self esteem who received inflated praise were less likely to take on a new challenge than other children, suggesting that the inflated praise actually backfired, perhaps because it set high standards that these children did not feel they could meet (Brummelman, Thomaes, Orobio de Castro, Overbeek, & Bushman, 2014). Discussion of this research has been valuable in educational settings, as praise in relation to participation rather than achievement has become more common.

BOX 2. GENDER DEVELOPMENT IN TRANSGENDER YOUTH

Gender identity is typically defined as an individual’s awareness of themself as male, female, or transgender. The term is thus different than terms such as sexual identity or sexual orientation, which typically refer to the sense of oneself as a sexual being and one’s romantic attractions (or lack thereof). Though there has been much research on gender development in children who identify with their natal sex, less is known about other children.

The TransYouth Project, led by developmental psychologist Dr. Kristina Olson, examines transgender children’s gender development. At the time of this writing, it is an ongoing longitudinal study of transgender children from North America (ages 3 to 12 years at the start of the study), though some early findings have been published (for a summary, see Olson & Gülgöz, 2018). These children have socially transitioned (e.g., they are referred to by a pronoun not traditionally used for their natal sex) and thus have significant parental support of their gender identities. Because of this, the researchers are cautious in generalizing the findings beyond similar samples.

The TransYouth Project is the first of its kind, researching gender development in transgender youth using quantitative empirical methodologies. The research thus far has examined the continuity and discontinuity of gender identity, researcher biases in assessing gender, and the implications of social support and transitioning on well-being in transgender and gender diverse youth. One finding thus far is that socially transitioned children’s gender development is quite similar to gender-typical peers and gender typical siblings. There are future research directions planned too, including larger and more diverse samples with children who have and have not socially transitioned.

PEER RELATIONSHIPS

Developmental psychologists have long claimed that relationships with peers are integral to children’s development. The interactions with similarly-aged ‘equals’ often allows the free exchange of ideas and criticisms, which can lead to the development of new concepts about how the world works. Cooperation with peers helps children develop social and emotional skills valued in the culture.

Among the different types of peer relationships, the study of friendship – and how the concept of ‘friend’ changes during development – has provided a large body of research. Having close, reciprocated friendships as a child is linked with positive outcomes even into young adulthood (e.g., Bagwell, Newcomb, & Bukowski, 1998). That said, friendships with individuals who promote dangerous or unhealthy behaviours can be costly (e.g., Simpkins, Eccles, & Becnel, 2008).

For some children and adolescents, peer relationships can include aggression, harassment, and violence, in person or online (i.e., cyberbullying). The consequences of being bullied are broad and include academic difficulties, stress-related illness, loneliness, biological changes within the brain, and suicide. By some accounts, 30% of children and adolescents in North America are bullied occasionally, with 7-10% bullied on a daily basis. Further, 75% of people say that they have been affected by bullying (www.PREVNet.ca).

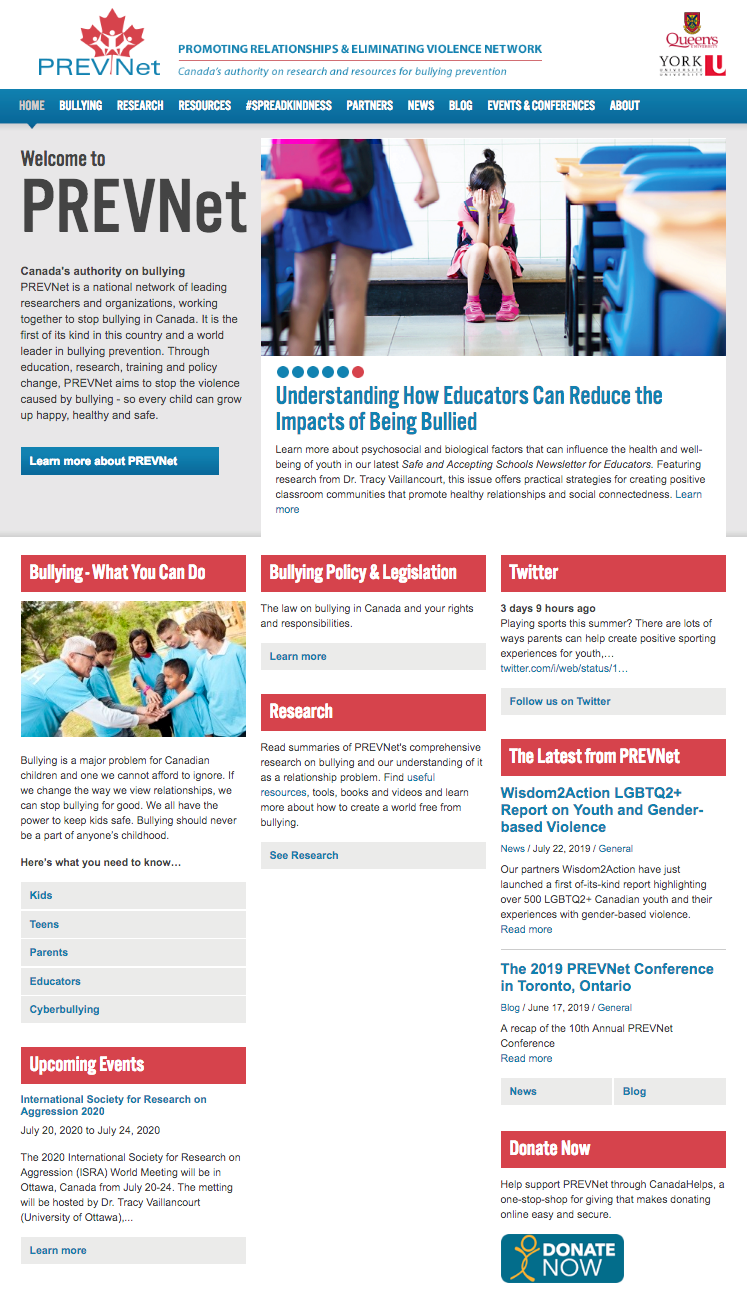

Developmental psychologists have been working with organizations to connect science to practice and practice to science, in turn creating and evaluating programs that promote positive relationships. For example, PREVNet (Promoting Relationships & Eliminating Violence Network; Figure 5) is a network of 130 Canadian research scientists, 183 graduate students, and 62 national youth-serving organizations (e.g., the Boys and Girls Club of Canada) that began in 2006. PREVNet focuses on education, assessment, intervention, and policy.

Initially, Canadian youth-serving organizations had few resources and opportunities to connect with each other and engage with researchers. Organizations like PREVNet, though, can bridge the gap between academic research, public policy and practices by connecting university researchers with organizations and communities. Indeed, since PREVNet began in 2006, the proportion of students in Canada who report bullying others has decreased by 62%, and the proportion of students who report both bullying others and being victimized has dropped by 44%. This decrease is likely in part a result of the work of all members of PREVNet and its cumulative impact across the country.

BOX 3. EMOTION REGULATION

In developmental psychology, the study of emotions occurs at many levels: neural responses, physiological responses such as heart rate, the subjective feelings associated with emotions, the recognition of others’ emotions, and the cognitive processes that can influence these different levels (e.g., Siegler et al., 2018).

Here, we highlight one aspect of emotional development: the ability to regulate one’s emotions. Though we have situated this ‘box’ within the social development section of this chapter, the topic actually bridges social and cognitive development. Regulating emotions can entail cognitive processes, including inhibitory control, reassessment of goals, and creation of new behavioural strategies. But, emotion regulation can also occur in a more social context, such as the co-regulation that can occur with parents or peers.

Emotion regulation plays an important role in well-being, with implications for anxiety and depression. Researchers in both developmental and clinical psychology often work together to apply research findings in the creation of interventions. One example is the use of video games that allow children with moderate to high levels of anxiety to practice controlling their stress. The game MindLight, created by developmentalist Dr. Isabella Granic along with a team of researchers and game designers, lets children virtually explore a dark mansion with a light that becomes brighter as they relax. Because the game is fun and engaging, children get repeated experience controlling their own anxious emotions as they play. Evaluating the effectiveness of the game is ongoing, and comparisons are being made to existing interventions including traditional cognitive behavioural therapy (e.g., Schoneveld et al., 2016; Wols, Lichtwarck-Aschoff, Schoneveld, & Granic, 2018).

SECTION RECAP

This section has provided a brief summary of social development, with emphasis on early interactions with caregivers, the development of a sense of self, and peer relationships. In each case, examples of how research findings have been applied — in various contexts (e.g., education, parenting) and with various goals (e.g., public policy) — have been presented.

Underlying our social interactions, though, are cognitive processes that support our interpretation of others’ behaviour and guide our decision-making. In the next section, we will provide an overview of some major research areas of cognitive developmental psychology and give examples of applications of the work.

-

COGNITIVE DEVELOPMENT

In a general sense, cognitive developmental psychologists study how our abilities to acquire, store, and process information develop. A more specific definition of ‘cognition’, though, is the “mental processes and activities used in perceiving, remembering, thinking, and understanding, and the act of using these processes” (Ashcraft & Klein, 2010, p. 9). Cognitive processes, therefore, are internal, occurring inside the brain. Because of this, cognition is typically inferred from behavioural or neural measures during carefully designed experiments.

This section will provide examples of research on cognitive development, noting how the findings can apply to other areas of the field of psychology as well as other disciplines and nonacademic communities. That said, many cognitive developmental psychologists conduct ‘basic science’, remaining agnostic with regard to any application to, for example, health or education. Indeed, the basic science underlying any effective application or intervention will take many years to complete, and the potential applications may only be realized after a large body of findings have been amassed and interpreted. Knowing this, it is important to approach the claims that specific toys or videos will make children ‘smarter’ with dose of healthy skepticism (e.g., Schellenberg & Hallam, 2005).

PERCEPTION AND EARLY COGNITIVE DEVELOPMENT

Decades of research with humans and nonhuman animals have led to the conclusion that the wiring of a species-typical brain is, in part, a result of experiences within a species-typical environment (e.g., voices, movement, three-dimensional objects). The brain is thus thought to ‘expect’ certain input from the environment to fine-tune itself by strengthening or pruning synapses. This experience-expectant plasticity has benefits (other areas may be able to take over when localized damage occurs), but it also has costs. If the ‘expected’ environmental information is not there, then development can be compromised.

Findings from infants who are born with cataracts that obscure vision demonstrate a cost of experience-expectant plasticity. Developmental psychologists have found that children who have cataracts medically removed later in development have greater visual impairment than those who have them removed earlier (see Maurer, 2017, for review). Research such as this has led to modern practices of early removal of cataracts when surgery is possible, with the aim of providing the infant visual system with the experiences that are important for development.

But, how do we even know what infants see when they cannot verbally communicate to us about their perceptions? Though there are many methodologies that capitalize on different infant behaviours such as reaching or sucking, there has been a long history of measuring infants’ looking behaviour. Experimental procedures using a habituation/dishabituation design, for example, capitalize on infants’ initial interest in new things, as well as their waning interest over time. In a typical set up, a visual stimulus (e.g., a striped object) is placed in front of an infant repeatedly. For the first few minutes, infants spend the majority of the time looking at the stimulus, but over time, they habituate to the stimulus and begin to look elsewhere more and more. When this looking-away behaviour reaches pre-determined criteria, a new stimulus is presented (e.g., a differently patterned object). Increased looking to this new stimulus is called dishabituation, and suggests that an infant is able to differentiate between the two stimuli. Using this type of methodology, cognitive developmental psychologists have been able to examine early perception and cognition in relation to objects (e.g., infants’ early sense of number, Box 4) and people.

A common methodology that is used to examine infant auditory discrimination is known as the conditioned head-turn procedure. At the start, infants are trained that when a change in an ongoing sound occurs, a fun toy appears to their side. When they learn this association, they readily turn their head in the direction of the upcoming toy if they hear the change. Using this procedure, developmental psychologists have examined how infants discriminate among different speech sounds. For example, 7-month-old infants growing up in English speaking households would turn their head when a speech sound common in English changed to a speech sound common in Salish, a language from coastal British Columbia, Canada. Intriguingly, 1-year-olds and adults with no experience with Salish find it very difficult to differentiate these sounds (e.g., Werker & Tees, 1984). Thus, there appears to be a time in early development in which our auditory perception allows for this discrimination, but with increased exposure to the predominant language in our environment, we narrow our perception. Although this may seem detrimental – and perhaps the opposite of how we usually think about development – the narrowing and focus may underlie the attainment of expertise.

BOX 4. NUMBER AND MATHEMATICS

What does cognitive developmental neuroscience have to do with mathematics education? A lot, actually. Many developmental psychologists have been focusing their research on how children learn about numbers using both behavioural and brain-imaging methods.

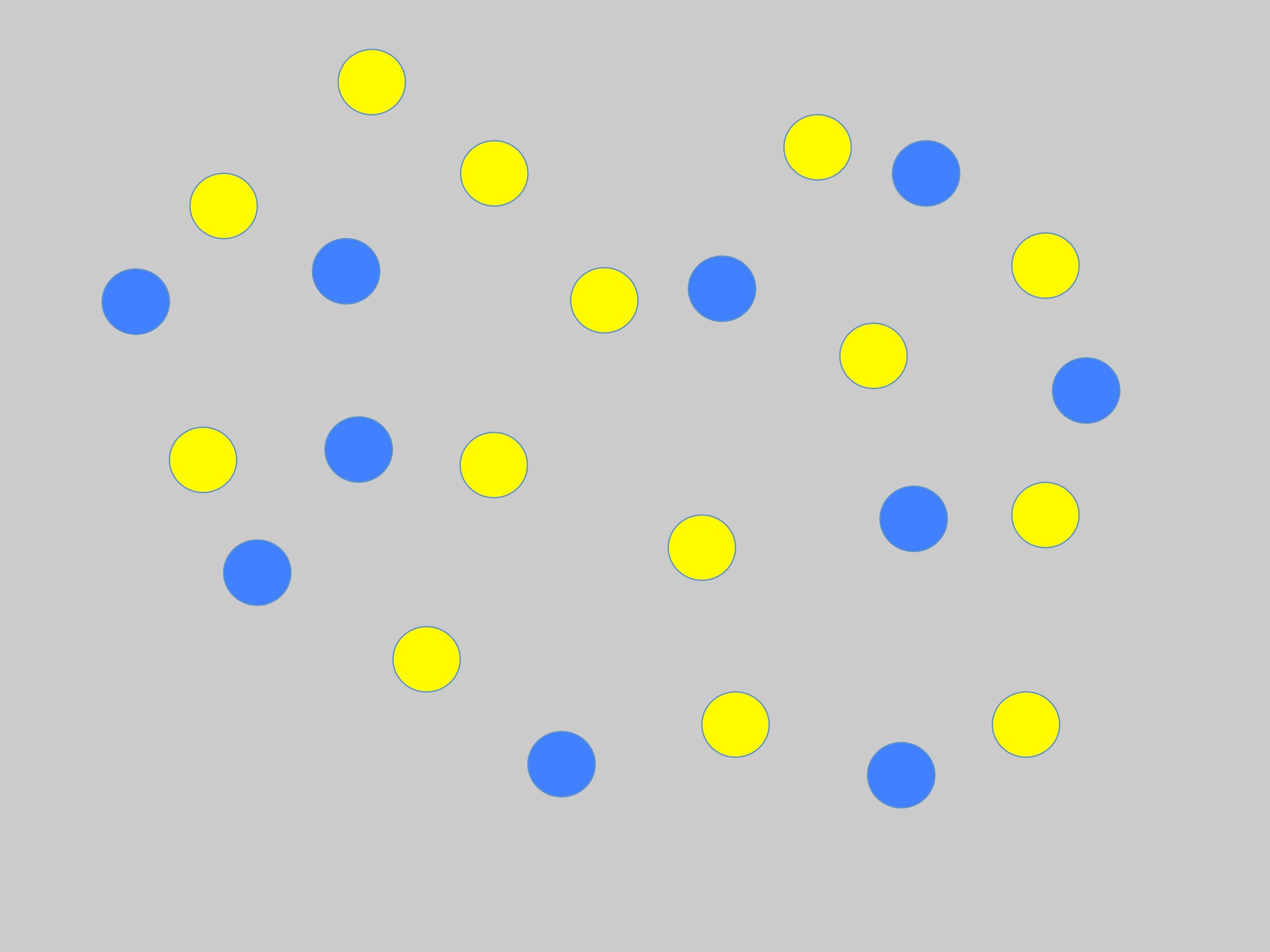

Young infants (and many nonhuman animals) can notice the difference between an array of, say, 8 dots and an array of 4 dots. We are capable of estimating numerical magnitude and discriminating between magnitudes, even at a very young age. (To try an adult version of this task in which both arrays are presented together, quickly look at Figure 7 without explicitly counting the dots. Are there more yellow or blue dots?)

Of interest to many researchers is the role these early representations play in the acquisition of symbolic number, such as Arabic numerals and number words (e.g., Feigenson, Libertus, & Halberda, 2013; Sokolowski, Fias, Ononye, & Ansari, 2017; Xenidou-Dervou, Molenaar, Ansari, van der Schoot, & van Lieshout, 2007). Does, for example, the development of basic magnitude processing impact the development of arithmetic skills? If so, what might this mean for mathematics education?

Developmental psychologists are also examining children who have severe difficulties with arithmetic (developmental dyscalculia). For example, Dr. Daniel Ansari uses behavioural and functional neuroimaging methods to study the causes and neural correlates of developmental dyscalculia (e.g., Bugden & Ansari, 2016). By partnering with educational psychologists, he aims to apply research findings to the classroom. For more information about the project, see: http://www.numericalcognition.org/media.html

LANGUAGE DEVELOPMENT

Developmental psychologists have a long history of studying language development, considering important aspects such as the perception and discrimination of speech sounds and the ways in which children learn the meanings of words. Related research focuses on how children learn to read. The area is broad, and entire university courses can be designed to introduce the topic. Here, we will focus specifically on the role of adults in children’s language learning and critical periods within development.

Perhaps counter-intuitively, adults do not actively teach language as much as you may think. Parents, for example, do not often explicitly teach grammatical rules. Instead, much of the learning comes from exposure to language. Parents will use infant-directed speech (higher pitch, with exaggerated intonation) when talking to an infant, and the speech emphasizes words for objects in the environment. During these ‘conversations’, children will also pay attention to the speaker’s focus of attention (via eye gaze, pointing, etc.) and use these pragmatic cues to determine what object the speaker is likely labeling.

Imagine, however, if a child does not have any exposure to language. Fortunately, such a situation is rare, but there are documented cases of abused children who were not exposed to language with any consistency. Children who were rescued from abuse later in development did not successfully learn language, even after living in a social and loving household. Similar findings also come from situations in which there was no abuse, yet children were not diagnosed with deafness and, thus, there was no exposure to sign language until later childhood. There appears to be a critical period within the first 4-5 years of life in which exposure to language is integral to language development.

The study of bilingual children and adults further supports the importance of a critical period. Adults who were exposed to a second language during their first three years of life show brain activation patterns to the second language that are similar to the patterns in monolingual adults who are listening to their native language. Those who learn a second language later, however, show different patterns (e.g., Weber-Fox & Neville, 1996).

But, how do children manage to learn two languages at once? A classic, but now unsupported view was that learning more than one language would negatively impact learning more generally. While it is the case that children learning two languages may learn each more slowly than children exposed to only one, the developmental ‘lag’ quickly disappears with age. These findings are important to policies around bilingual education, suggesting that immersion programs will not hinder learning (e.g., Holobow, Genesee, & Lambert, 1991).

UNDERSTANDING OTHERS

Many topics already covered in this chapter relate to children’s developing understanding of the people around them. Attention to faces in early infancy, forming attachments to parents, and perceptual systems that parse the sounds of human language all support our ability to make sense of others’ behaviour and predict their future behaviour. The importance of these and other social cognitive abilities can perhaps best be appreciated when we consider how hard it is to navigate human society when the abilities are limited, as is thought to be the case for individuals with autism spectrum disorder (Box 5).

Key to our mature understanding of others is the seemingly human-unique suite of social cognitive skills that researchers refer to as theory of mind. Theory of mind is our understanding that the behaviour of other people is caused by their internal mental states, such as their intentions, desires, and beliefs. We cannot directly see others’ beliefs, but we can infer them based on the context, past behaviour, and current behaviour. You will likely predict, for example, that a friend will look for his book on his desk where he left it, even if you borrowed it when he was away and left it on your own desk. You know that his belief as to the location of the book is different from your own knowledge.

This type of inference undergoes a major change in the preschool years, and developmental psychologists have found that many social, cognitive, and neurodevelopmental factors shape the timeline of theory of mind development. Some studies, for example, use electroencephalography (EEG), a procedure that measures electrical activity of the brain over time using electrodes placed on the scalp, to assess ways in which brain maturation might be specifically related to developments in preschoolers’ theory-of-mind (e.g., Sabbagh, Bowman, Evraire, & Ito, 2009). Related research considers the role of neurotransmitter systems (e.g., dopamine) in shaping children’s social cognitive development (Lackner, Sabbagh, Hallinan, Liu, & Holden., 2012).

Our brains develop within our social and cultural environments, though, as you have likely recognized throughout this chapter. Thus, theory of mind research also considers how brain maturation interacts with relevant, everyday social experiences. For example, parents’ use of mental state talk with their young children is correlated with children’s later theory of mind development (e.g., Ruffman, Slade, & Crowe, 2002). It is possible that mental state talk provides them with fact-based knowledge about mental states, and it might help children to start to take the perspective of others by using their own perspectives as a comparison.

As noted, the ability to reason about others’ mental states is integral to efficiently navigating our social world. There are, thus, direct applications of the study of theory of mind to the study of autism, but the applications can extend far more broadly. For example, those studying how children learn from others (social learning) consider how children differentiate knowledgeable from ignorant individuals (e.g., Poulin-Dubois et al, 2016), and researchers who are characterizing the factors that encourage or discourage bullying and prosocial behaviour consider underlying social cognitive reasoning (e.g., Dunfield & Kuhlmeier, 2013). As a further example, clinical psychologists work with developmental psychologists to examine the role of theory of mind in the etiology, pathology, and phenomenology of depression in adolescents and adults (e.g., Zahavi et al., 2016).

BOX 5. AUTISM

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) usually emerges in the first three years of life. It is a developmental disorder, and as such, it is particularly important to diagnose and treat ASD early in life (though there is currently no ‘cure’).

One characteristic of ASD is a difficulty and disinterest in engaging in social interactions. Many researchers have suggested that this key feature of ASD has foundations in early infancy. Whereas typically developing infants attend to faces and biological motion, infants who later are diagnosed with ASD show deficits in attention to social stimuli (e.g., Klin, Lin, Gorrindo, Ramsay, & Jones, 2009; Osterling & Dawson, 1994). This inattention may derail subsequent experiences, leading to inattention to higher-level social information. In this way, development is driven to more severe dysfunction, and deficits are ultimately seen in additional domains, such as language development.

Developmental psychologists have been working for many years to find reliable predictors of ASD during the first year of life. New findings from the study of typical cognitive development are often considered in relation to children who are at risk of developing ASD (e.g., siblings of already-diagnosed children). Until we have reliable predictive tests, though, diagnosis cannot occur until behavioural symptoms emerge in later toddlerhood. Treatment is often delayed, potentially missing a developmental period in which intervention may be particularly successful in mitigating some of the impairments seen in ASD.

SECTION RECAP

This chapter has thus far been divided into two areas of developmental research: social and cognitive. As you likely noticed, the lines separating the areas are at times ‘fuzzy’, yet there has been a tradition in developmental psychology to loosely organize around these two areas. This is not to suggest that the work occurs in two separate silos. For example, even research on children’s developing understanding of objects, including their understanding about the number of objects, will also consider the social environment. Learning about objects relies on not only on children’s perceptual development and recognition of physical causality, but also on how they learn from knowledgeable others about an object’s function and name. Number cognition develops within cultural systems that have symbolic count words, artifacts such as calculators and the abacus, and mathematics notation.

Perhaps in part due to the breadth of developmental psychology as a field, there are many relevant career paths that incorporate its theory and methodology, either directly or indirectly. In the next section, we provide examples of these careers, as well as some of the educational paths students can take.

-

EDUCATIONAL PATHS AND CAREERS

Most of the studies and the applications of research findings described in this chapter are the result of projects led by developmental psychologists who have completed a doctorate (e.g., Ph.D.) degree. The basic science underlying any novel application or intervention can take many years to complete (indeed, basic science is often completed with no application in mind). Along the way, though, the work is only possible through the combined work of many individuals with many different types of educational backgrounds and job experience.

Before discussing different educational and career paths relevant to developmental psychology, it is important to consider a distinction that will often confuse students early in their undergraduate training: How do developmental psychologists differ from child clinical psychologists? In fact, before reading this chapter, some students might have reasonably, though incorrectly, thought that only clinical psychologists consider applications of psychological research.

Developmental psychologists are interested in understanding the mechanisms of change by examining the interactions between nature (our genetic inheritance) and nurture (the physical and social environment). They are often interested in species-typical developmental paths, but intriguing individual differences may also be uncovered. Clinical psychologists tend to emphasize the individual differences, particularly those relevant to psychological health and well-being.

Many child clinical psychologists are primarily practitioners and see clients, which requires specialized training. Developmental psychologists typically do not have the requisite training to be registered as this type of “Psychologist” and instead engage in specialized research training. That said, some child clinical psychologists are scientist-practitioners and collaborate closely with developmental psychologists in research settings.

With this distinction in place, we can now consider the educational and career paths relevant to developmental psychology. As in most disciplines, the career opportunities will differ based on the level of education completed, so undergraduate training is presented separately from graduate training in this section. Also, similar to many disciplines, there are not many ‘hard and fast rules’; remember that there are many routes possible to reach your goals.

UNDERGRADUATE TRAINING

In North America, undergraduate degrees in psychology are not typically specialized in a particular area like developmental psychology (it is a general degree in Psychology), though psychology majors and other majors may choose to emphasize this coursework in their training. Many colleges and universities have courses that cover the field in general (Developmental Psychology) and courses that provide specific focus (Language Development, Infancy, Social-Emotional Development, Cognitive Developmental Neuroscience).

Knowledge gained from developmental psychology courses provides good preparation for graduate training in psychology, social work, speech-language pathology, occupational therapy, teaching, law, and public policy, among others. Some students take developmental psychology courses to complement their undergraduate and graduate training in education and even computer science (e.g., educational software development). Of course, some careers may be started without further training in graduate school – it is never too early to start looking at job advertisements and reading the professional profiles of people who have a career that interests you.

Resources for students can typically be found on their college or university campus, but online resources are also available from reputable organizations. Both the Canadian Psychological Association (CPA) and the American Psychological Association (APA) have subsections specific to developmental psychology, for example.

GRADUATE TRAINING

Those who apply to graduate school in developmental psychology typically hold an undergraduate degree in psychology, but it is not uncommon to have a background in neuroscience, biology, philosophy, linguistics, or another related field. Prospective students start their search by considering who they want to work with: Is there an individual or team whose research you find particularly relevant to your career goals? The next consideration is often the school itself: What resources (collaborators, funding, professional development, etc.) does the university provide?

In many programs, graduate students earn a master’s degree before continuing on to the Ph.D. degree. A master’s degree can prepare students well for some of the types of graduate training described above; for example, a master’s degree could be attained before or after law school with the goal of practicing family law. Individuals who earn a Ph.D. are considered experts in their field and have strong research, data analytic, and critical thinking skills that can be applied to many different settings.

Graduate training is perfect for people who enjoy discovery and problem-solving. Perhaps an underemphasized trait, though, is having an entrepreneurial spirit that motivates you to create the career you want. Developmental psychologists have created careers within both the academic and nonacademic sectors, using their skills in various ways, including the following:

RESEARCH AND TEACHING (typically with a Ph.D.)

Colleges/Universities

Government

Medical Centers

APPLIED/CONSULTING (typically with a Master’s or Ph.D.)

Software Development

Online Content Curation

Marketing

Youth Service (NGO’s)

Child Welfare Agencies

Education: Curriculum & Content

Education: Children’s Museums

Science Writing

Toy Design

SECTION RECAP

Developmental psychologists are well-versed in the key theories of their field. They can create empirical research methodologies to test new hypotheses, and they analyze the resulting data. They know how to critically evaluate claims and effectively communicate findings to other scientists as well as the broader community. In some cases, research findings become relevant to the development of new programs and interventions, which themselves must be evaluated empirically before implementation and policy change. Depending on their chosen career and level of education, people trained in developmental psychology may apply some or all of these skills in their work.

REFERENCES

Ashcraft, M. H., & Klein, R. (2010). Cognition. Toronto, CA: Pearson Education Canada.

Bagwell, C. L., Newcomb, A. F., & Bukowski, W. M. (1998). Preadolescent friendship and peer rejection as predictors of adult adjustment. Child Development, 69, 140-153. doi:10.111/j.1467-8624.1998.tb06139.x

Bartrip, J., Morton, J., & de Schonen, S. (2001). Responses to mother’s face in 3-week to 5-month-old infants. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 19, 219-232. doi: 10.1348/026151001166047

Bowlby, J. (1953). Child care and the growth of love. M. Fry (Ed.). London, UK: Penguin Books.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Brummelman, E., Thomaes, S., Orobio de Castro, B., Overbeek, G., & Bushman, B. J. (2014). “That’s not just beautiful—that’s incredibly beautiful!”: The adverse impact of inflated praise on children with low self-esteem. Psychological Science, 25(3), 728–735. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797613514251

Bugden, S., & Ansari, D. (2016) Probing the nature of deficits in the ‘Approximate Number System’ in children with persistent developmental dyscalculia. Developmental Science, 19, 817-33.

Damon, W., & Hart, D. (1988). Self-understanding in childhood and adolescence. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Donnellan, M. B., Trzesnieswski, K. H., Robins, R. W., Moffitt, T. E., & Caspi, A., (2005). Low self-esteem is related to aggression, antisocial behavior, and delinquency. Psychological Science, 16, 328-335. doi:10.1111/j.0956-7976.2005.01535.x

Dunfield, K. A., & Kuhlmeier, V. A. (2013). Classifying prosocial behaviour: Children’s responses to instrumental need, emotional distress, and material desire. Child Development, 84(5), 1766-1776.

Feigenson, L., Libertus, M. E., & Halberda, J. (2013). Links between the intuitive sense of number and formal mathematics ability. Child Development Perspectives, 7, 74-79.

Harter, S. (1999). The construction of the self: A developmental perspective. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Holobow, N. E., Genesee, F., & Lambert, W. E. (1991). The effectiveness of a foreign language immersion program for children from different ethnic and social class backgrounds: Report 2. Applied Psycholinguistics, 12, 179-198.

Klin, A., Lin, D. J., Gorrindo, P., Ramsay, G., & Jones, W. (2009). Two-year-olds with autism orient to non-social contingencies rather than biological motion. Nature, 459(7244), 257–261.

Lackner, C. L., Sabbagh, M. A., Hallinan, E., Liu, X., & Holden, J. J. (2012). Dopamine receptor D4 gene variation predicts preschoolers’ developing theory of mind. Developmental Science, 15, 272-280.

Maurer, D. (2017). Critical periods re-examined: Evidence from children treated for dense cataracts. Cognitive Development, 42, 27-36.

Nelson, C. A. III, Zeanah, C. H., Fox, N. A., Marshall, P. J., Smyke, A. T., & Guthrie, D. (2007). Cognitive recovery in socially deprived young children: The Bucharest Early Intervention Project. Science, 318, 1937-1940.

NICHD Early Childcare Network. (1997). The effects of infant child care on infant-mother attachment security: Results of the NICHD Study of Early Child Care. Child Development, 68, 860-879. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.1997.tb01976.x

O’Neill, A. C., Swigger, K., & Kuhlmeier, V. A. (2018). Make The Connection’ parenting skills program: a controlled trial of associated improvement in maternal attitudes. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 36(5), 536-547. doi: 10.1080/02646838.2018.1497779

Olson, K. R., & Gülgöz, S. (2018). Early findings from the TransYouth Project: Gender development in transgender children. Child Development Perspectives, 12(2), 93-97.

Osterling, J., & Dawson, G. (1994). Early recognition of children with autism: A study of first birthday home videotapes. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 24, 247-257.

Posada, G, Lu, T., Trumbell, J., Trudel, M., Plata, S. J., Pena, P. P., … Lay, K-L. (2013). Is the secure base phenomenon evident here, there, and anywhere? A cross-cultural study of child behavior and experts’ definitions. Child Development, 84, 1896-1905.

Poulin-Dubois, D., & Brosseau-Liard, P. (2016). The developmental origins of selective social learning. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 25(1), 60–64. doi:10.1177/0963721415613962

Sabbagh, M. A., Bowman, L. C., Evraire, L. & Ito, J. M. (2009). Neurodevelopmental bases of preschoolers’ theory-of-mind development. Child Development, 80, 1147-1162.

Schellenberg, E. G., & Hallam, S. (2005). Music listening and cognitive abilities in 10 and 11 year olds: The Blur effect. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1060, 202–209.

Schoneveld, E. A., Malmberg, M., Lichtwarck-Aschoff, A., Verheijen, G. P., Engels, R. C., & Granic, I. (2016). A neurofeedback video game (MindLight) to prevent anxiety in children: A randomized controlled trial. Computers in Human Behavior, 63, 321-333. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2016.05.005

Siegler, R., Saffran, J. R., Graham, S., Eisenberg, N., DeLoache, J., Gershoff, E., & Leaper, C. (2018). How children develop (Canadian 5th ed.). New York, NY: Worth Publishers.

Simpkins, S. D., Eccles, J. S., & Becnel, J. N. (2008). The meditational role of adolescents’ friends in relations between activity breadth and adjustment. Developmental Psychology, 44, 1081-1094.

Simpson, J. A., & Belsky, J. (2008.). Attachment theory within a modern evolutionary framework: Theory, research, and clinical applications. In J. Cassidy & P. R. Shaver (Eds.), Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications (2nd ed., pp. 131-157). New York, NY: Guilford.

Sokolowski, H. M., Fias, W., Ononye, C., & Ansari, D. (2017) Are numbers grounded in a general magnitude processing system? A functional neuroimaging meta-analysis. Neuropsychologia, 105, 50-69.

Rovee-Collier, C. (1999). The development of infant memory. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 8, 80-85. doi: 10.1111/1467-8721.00019

Ruffman, T., Slade, L., & Crowe, E. (2002). The relation between children’s and mothers’ mental state language and theory of mind understanding. Child Development, 73, 734-751.

Rutter, M., Beckett, C., Castle, J., Kreppner, J., Stevens, S., & Sonuga-Barke, E. (2009). Policy and practice implications form the English and Romanian Adoptees (ERA) study: Forty-five key questions. London, UK: British Association for Adoption and Fostering.

Rutter, M., O’Connor, T. G., & The English and Romanian Adoptees (ERA) Study Team. (2004). Are there biological programming effects for psychological development? Findings from a study of Romanian adoptees. Developmental Psychology, 40, 81-94.

Weber-Fox, C., & Neville, H.J. (1996). Maturational constraints on functional specializations for language processing: ERP and behavioral evidence in bilingual speakers. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 8, 231-256.

Werker, J., & Tees, R.C. (1984). Cross-language speech perception: Evidence for perceptual reorganization during the first year of life. Infant Behavior and Development, 7, 49-73.

Wols, A., Lichtwarck-Aschoff, A., Schoneveld, E.A., & Granic, I. (2018). In-game play behaviours during an applied video game for anxiety prevention predict successful intervention outcomes. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 40, 655-668. doi:10.1007/s10862-018-9684-4

Xenidou-Dervou, I., Molenaar, D., Ansari, D., van der Schoot, M., & van Lieshout, E. C. (2017) Nonsymbolic and symbolic magnitude comparison skills as a longitudinal predictors of mathematical achievement. Learning and Instruction, 50, 1-13.

Zahavi, A. Y., Sabbagh, M. A., Washburn, D., Mazurka, R., Bagby, R. M., … Harkness, K. L. (2016). Serotonin and dopamine gene variation and theory of mind decoding accuracy in major depression: A preliminary investigation. PLOSOne. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0150872

Zeanah, C. H., Koga, S. F., Simion, B. , Stanescu, A. , Tabacaru, C. L., Fox, N. A., … BEIP Core Group. (2006). Ethical considerations in international research collaboration: The Bucharest early intervention project. Infant Mental Health Journal, 27: 559-576. doi:10.1002/imhj.20107

Please reference this chapter as:

Kuhlmeier, V. A., Mayne, K., & Craig, W. (2019). Developmental Psychology. In M. E. Norris (Ed.), The Canadian Handbook for Careers in Psychological Science. Kingston, ON: eCampus Ontario. Licensed under CC BY NC 4.0. Retrieved from https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/psychologycareers/chapter/developmental/