2 Introduction to Career Development

Cathy Keates, Director, Queen’s University, Career Services

Miguel Hahn, Head Career Counsellor, Queen’s University, Career Services

INTRODUCTION

Charting your career path beyond university can be a surprisingly complex experience – potentially both exciting and daunting at times, it can be all too easy to put off thinking about your future until some other time. To ease potential stress, and help find your way in an unknown terrain, it can be helpful to have a map to make more informed choices. In this chapter we will help you start building your own map of your future as we look at the topic of careers from a number of different perspectives.

We’ll examine common questions of Psychology students, look at some key labour market trends and information, and learn about leading career development theories. Then we’ll boil this all down to look at how you can use it to make the most of your time studying psychology, learn about yourself, and make good career decisions. From this foundation of a broad perspective on career development, you will be better positioned to make sense of the various career paths you will be exploring throughout the remainder of this text.

PSYCHOLOGY DEGREES + CAREER PATHS – WHAT CAN I DO WITH A PSYCH DEGREE?

Before you dive in to the wealth of information in this text about all the exciting career possibilities that lay ahead, and ideas about how to navigate your career in this chapter, we want to address a few key questions and concerns that we hear from Psychology students about career options, grad school, and what you are learning in the classroom.

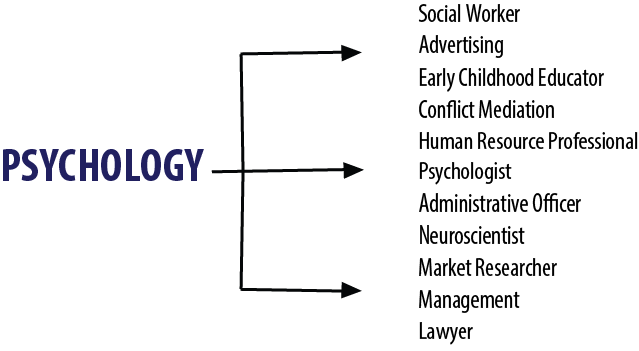

What can I do with a Psych degree? – COMMON CAREER PATHWAYS

One of the most common questions asked by students in Psychology is “What can I do with a Psych degree?” A reasonable question, hoping for a clear answer to provide future direction. The truth is a bit murkier than the predictability you might be expecting.

As a student you may be used to linear relationships between steps in your education – you complete secondary school and then go to postsecondary, you take Psych 100 to be able to take Psych 200, etc. It is easy to expect to keep moving on a predictable track to specific advanced degrees and jobs. The reality is that after graduation, graduates with Psych degrees head in many directions, some highly related to their undergraduate studies, and some less obviously so.

This textbook will shed some light on some of the more common pathways for psychology graduates, as well as a few destinations you might not have anticipated. With a quick search on LinkedIn you can confirm this for yourself. You’ll see psychology graduates working as psychologists, psychiatrists, counsellors, educators, and researchers, but also people working in marketing, human resources, law, non-profit, and a multitude of other professional fields. What does this mean for you? It means that you have options – you can continue to move in directions more explicitly related to psychology, but you can also give yourself permission to explore other destinations. In fact, only roughly half of students who study any discipline at university end up moving into directly related fields (Council of Ontario Universities, 2016).

How to search alumni on LinkedIn:

- Login to Linkedin (create an account if you haven’t yet)

- In the search bar at the top of the page, search for your school’s name.

- On your school’s page, click on the “See Alumni” button to access the database of students and alumni from your school.

- Keep in mind that if you click on someone’s page they will be notified, so you may either want to set your privacy settings to anonymous, or make sure you are comfortable with them knowing you clicked!

Why is this the case? There are a number of factors that influence the steps someone takes in their career. Although the fact that you have chosen to study psychology might tell us something about some of your aptitudes and interests, you will still find a wide degree of variety in the make up of your class. Not all psychology students are the same – each person in your class has their own life experiences, personality, skills, and values – and these will strongly influence directions you are inspired to pursue. Beyond the internal factors, there are a host of external variables that will affect this as well – parental and peer influences, networking connections, chance opportunities, barriers encountered, labour market forces, funding, and more will all alter your career trajectory in complex ways. We will get into a deeper analysis of understanding career development later in this chapter looking at the labour market and helpful career theories and models that have been refined over the last century to help us get a grasp on this complex dynamic.

Should I go to graduate school? – FURTHER EDUCATION & TRAINING

Another very common question psych students ask is “Should I go to graduate school?” Where do you go from an undergraduate degree? Sometimes, because you are surrounded with professors and graduate students who have all done advanced degrees, you might get the impression that your only route to success is to pursue a long academic track towards a PhD or other advanced credentials. While this can certainly be a rewarding path, it is not for everyone. In fact, Rajecki and Anderson (2004) state that the majority of psychology students enter the labour market after graduation, rather than pursue additional training. And just as there are a variety of career directions, there are just as many routes you can take to get to those destinations. Once you start exploring, you will come across programs ranging from short certificates and courses, to post-grad diplomas at colleges, professional course-based master’s, practicum focused master’s, research-based masters, law school, med school, and more. It can be very easy to get overwhelmed trying to sort through all of these possibilities.

How can you make an informed decision? Getting a clearer sense of career direction and long-term plan can help keep you grounded while considering your next steps. Throughout this text you will be refining your own sense of direction in terms of what fits you and your life, and learning about developing the necessary qualifications and experience to be a competitive candidate in your field of interest.

What am I learning studying psychology? THE VALUE OF YOUR DEGREE

Even though you spend so much time in classes and working on academic projects, many students struggle to articulate what they have actually been learning, especially when it comes time to apply to jobs or further education. The good news is that your studies in psychology are providing you with valuable skills that employers want. What exactly are they looking for?

According to a recent Business Skills Council of Canada Skills Survey, the top 5 skills employers look for in entry level hires are (Business Council of Canada, 2018):

- Collaboration and interpersonal skills

- Communication skills

- Problem-solving skills

- Analytical capabilities

- Resiliency

What are the specific skills and learning outcomes associated with studying psychology at the undergraduate level? The APA presents detailed information outlining their expectations (American Psychological Association, 2013):

- Knowledge base in psychology including key concepts, themes, domains, and applications

- Scientific inquiry and critical thinking including reasoning, information literacy, problem solving, and research

- Ethical and social responsibility in a diverse world

- Communication including effective writing and presentation skills

- Professional development including applying psychological content to career goals, self-efficacy, project management, teamwork, and meaningful professional direction for life after graduation

If you compare the skills you can get from your degree with what employers are looking for, you can quickly see that you are well positioned with a strong foundation for future success. For a more specific accounting of what you can expect to learn from your program, you can consult learning outcomes associated with the program, individual courses, or materials like the Queen’s University Majors Maps that outline key skills and career options tied to each program. In the next section we will take our investigations further by looking at labour market information and how it can help you navigate your career development.

Where are the jobs? – LABOUR MARKET INFORMATION

The future ain’t what it used to be. – Yogi Berra

Previous generations might have experienced periods of relative stability and predictable career progression, but in our modern society change is the new normal. With significant technological advancements transforming the ways we work, information technology transforming our cultures, and political, ecological and cultural changes affecting every aspect of our lives, it can be hard enough to predict the weather a month from now, let alone make informed career plans for years into the future. “Chaotic systems display … a lack of predictability at the micro level, while at the same time appearing to have a degree of stability at the macro level” (Bright & Prior, 2005). There is no one answer to “Where are the jobs?” because there is too much change to predict the future to that micro level. However, there are some broad changes at the macro level that we can explore.

Broad trends affecting world of work

With the nature of working rapidly changing, understanding the future of the labour market can prove difficult. Here we will look at key forces that will influence the way work is viewed in the future; technology, globalization, demography, society, climate change, and energy resources (Gratton, 2011).

The influence of technology and globalization across the world is perhaps the most obvious. Technology has consistently driven long-term economic growth, resulting in continuous productivity gains since the mid-1990s – a narrative that is expected to continue as the world’s knowledge becomes increasingly digitized.

4 Major Trends Shaping the Future (Gratton, 2011)

- Technology

- Globalization

- Demographic and social shifts

- Climate change & energy systems

Globalization affects countries in different ways. Increased competition and trade have allowed certain countries to benefit as it becomes more cost-effective to move both goods and information. However, this has also resulted in markets that are arguably more unstable as compared to markets in the 20th century. With the development of global financial markets, undesirable market effects can spread very quickly on a global scale, such as the market crash on September 29, 2008 (Bostan, 2009).

With this increasing global connectivity, societal mindsets are shifting as consumers are exposed to more choices and are faced with an evolving definition of what it means to meet their needs (Gratton, 2011). This is further influenced by changes in the world’s demographic and societal structure. Developed countries are facing a rapidly aging population concurrent with a low birth rate. While increasing longevity means that people are able to contribute to the labour market for a longer period of time, governments are also faced with restructuring their policies to better support the population. Additionally, differing attitudes between generational cohorts will likely also contribute to a restructuring of work. Generation Z, who will be around 35 years old in 2025, is known primarily for its connectivity. As more of this generation enters the work force, they will play a larger role in reshaping the workplace to meet their expectations and needs.

The final restructuring that will inevitably occur concerns the use of energy resources and their related contribution to climate change. A reorganization appears inescapable in the future – whether it is a reluctant adaptation of the present energy framework as resources become increasingly strained, or a construction of a new energy framework that would integrate networks both locally and globally to create a new system of sustainability. All of these trends combined will continue to reshape the future of work – how we work, with who, and where.

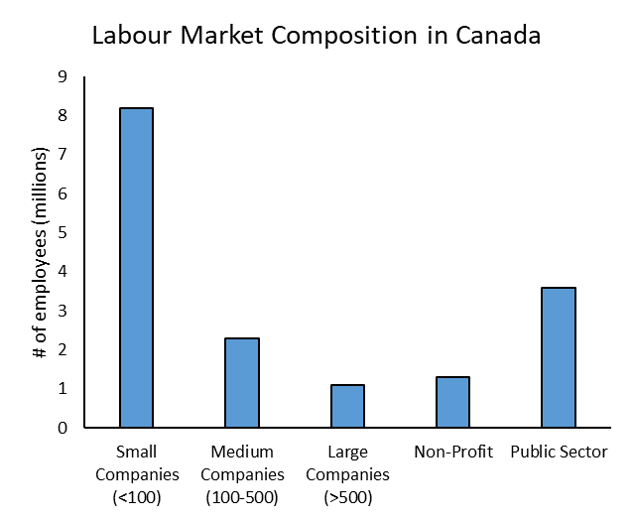

Where people work

Shifting from a global perspective to a national perspective, it can be enlightening to see where people in Canada actually work. A common assumption is that most people work in large companies, but in fact large companies only employ a small percentage of the population, with the majority of people working in small companies of less than 100 people (Government of Canada, 2016), and almost a third working in non-profit (Statistics Canada, 2005) and the public sector (Fraser Institute, 2015).

Small Company (less than 100 employees) 8.2 Million

Medium Company (between 100 and 500 employees) 2.3 Million

Large Company (more than 500 employees) 1.1 Million

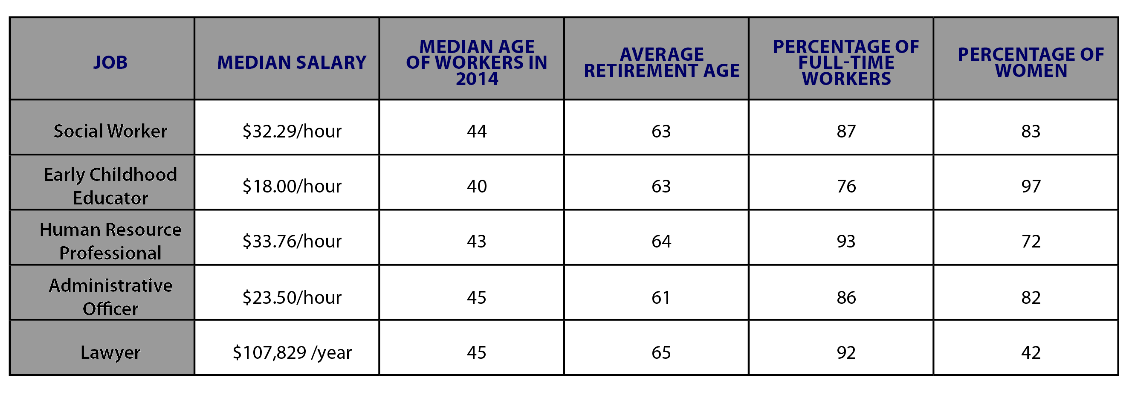

Outlook by Occupation

Occupational outlooks can be a valuable source of information in trying to predict future demand for careers of interest. Using resources like the Canadian Job Bank website, you can search by occupation to access information projecting demand 10 years into the future, as well as wage information, skills, job postings, and more. Below is a quick sampling of some of the kinds of information you may find (Government of Canada, 2018c):

Outlook by Area of Study

Government data is also available by degree area and level, and can reveal some interesting details.

Searching the Canadian Job Bank website for graduates of psychology Bachelor’s Degree programs (Government of Canada, 2018a):

- Unemployment is 6%

- Median salary is $44,639.00

- 40% work in jobs closely related to field of study, 28% somewhat related, and 32% not related

- 60% of graduates continue studying after graduation

For graduates of psychology Master’s Degree programs (Government of Canada, 2018b):

- Unemployment is 4%

- Median earnings are $61,537

- 61% work in jobs closely related to their field of study, 25% somewhat related, and 14% not related

- 40% of graduates continue studying

So what does all of this data mean to you?

Getting information about future trends, salary surveys, and occupational outlooks can give you a sense of what is going on in the world of work to help you make informed decisions. Knowing, for example, that roughly half of graduates of psychology end up in work closely related to their studies might encourage you to consider other possibilities. Seeing the higher salary and employment rates of Master’s degree holders might lead you to think that further education could be a good investment. Or you could see the labour market outlook for psychologists in the Maritime Provinces or the prairies is better than Ontario and consider moving there for better job prospects (Government of Canada, 2018c).

While potentially quite useful, this information should be used with caution. In the dynamic modern workplace, changes can happen quite quickly. Much of the information included in job futures projections may be based on census information or graduate surveys that could be already a few years old.

Most importantly, the information speaks to general patterns and averages, but not to individuals. Although there may be broader trends or pathways that others follow, they need to be considered in the context of your specific life circumstances and particular needs. It can be tempting to follow the money, or seek out the hot jobs – but this is not a guaranteed road to success. In the 1990s, students were flocking to studying computers because the job market was so hot in IT – but when the market contracted suddenly and the dot-com bubble burst, many computing students struggled to find work (U.S. National Center for Education Statistics, 2017).

A balanced approach to decision making that considers environmental conditions and personal factors together is more likely to lead to good decisions than a strategy based on either aspect alone. To help you form your own grounded perspective way of looking at careers, we will look at some of the most prominent models and thinkers influencing career development theory today in the next section.

MODELS & WAYS OF LOOKING AT CAREERS – HOW DO I THINK ABOUT CAREERS?

Much like the other topics you have studied in your degree so far, the topic of “career development” has had a lot of academic study – with years of theory development and research looking at how people develop careers.

The central questions of career development theories have been:

- How do individuals make decisions about what career to pursue?; and

- How do career paths develop over time?

This chapter will be useful to you if you are interested in “career development” from an academic perspective, but you needn’t be. As we review theories of career development, we will extract information and strategies that you can use as you map out your own future career path(s). We will review several approaches to career development, focusing on those theorists and topics that may be most helpful to you as you think about your own career decisions.

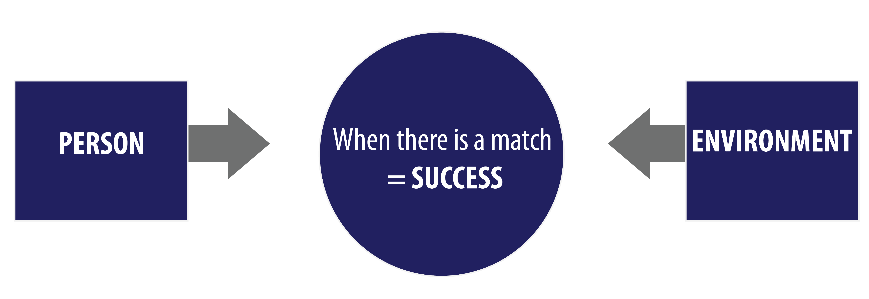

Person-Environment Fit

A foundational theory and concept in career development is person-environment fit, credited to Frank Parsons working from the early 1900s (Neault, 2014). The central idea of person-environment fit is that the better the match between a person (namely their traits such as skills, interests, and values) and the environment (such as the needs and demands of a specific occupation and workplace) the greater likelihood of success and happiness for that person.

In practical terms, following the person-environment fit model to make a career decision would lead to activities such as first assessing your skills, interests, and values, then gathering data about occupations, and then comparing you (the person) and the occupations (environment) and looking for the “best fit” career choices.

This simple idea of person-environment fit continues to be the foundation of most career development activity (and in the next section of the chapter we will present some activities that you can use to learn more about yourself and about potential occupations as you look for fits). However, while useful as a foundation, this approach is too one dimensional. Simply looking at fit between an individual person’s needs and an occupation’s needs, is not representative of the actual complexity of career decisions and career development over one’s lifespan. In addition it leaves out significant other variables that impact what options are available to many people.

Constraints on Person-Environment Fit

While person-environment fit is a useful starting point, a key criticism is that it assumes that all individuals are choosing from all possible environments (jobs, organizations). Theorists such as Gottfredson (1996) argue that choosing a career is not just about your psychological self, but also your social self. Through your career choice, you are “placing [yourself] in the broader social order” (p. 181). This draws attention to the impact of social aspects such as gender and social class. Her theory of Circumscription and Compromise asserts that your self-concept and your images of occupations are impacted by social factors. Circumscription is a narrowing of perceived options – “the progressive elimination of unacceptable alternatives” to those that are considered socially acceptable (p. 187). Compromise is then the process of editing your preferred career options based not just on what is most compatible with you, but what you perceive as most acceptable. For example, some might believe that certain careers are only appropriate for certain genders such as nursing for women.

Are there career options that you think are not “acceptable” for you? Based on your gender identity? Based on your social class? Based on other social variables? Are any of those careers options that you feel are compatible with your skills and interest, but you’ve eliminated them as options because of perceived “unacceptability”?

Gottfredson’s concepts of circumscription and compromise illuminate how there is more to a career decision than assessing the fit between a person and the environment; there can be internal reactions to external factors, and these internal reactions change perceptions of what careers might be possible and acceptable as you plan your career options.

The Decade After High School

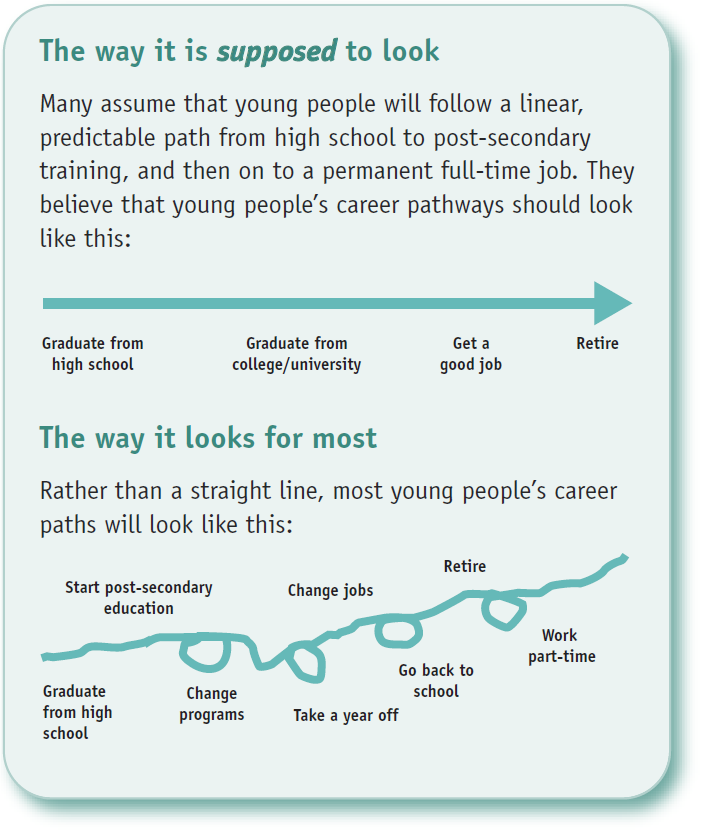

While it is helpful to think about how to plan your career path, planning does not represent the full experience of how careers actually unfold. Many people think of career development as a ladder – a series of planned steps leading up to greater and greater things. In reality, people’s career trajectories are far more disordered. Recent research with youth in Canada in their decade after graduating from high school provides an interesting illustration of this (Campbell & Dutton, 2015).

Researchers interviewed 100 young people in four Canadian cities. They found that these youth used three styles of moving forward:

- navigating – youth who used navigating had a plan and were following it

- exploring – those using exploring did not know exactly where they wanted to end up, but were actively trying out different things to learn more about themselves and about career options

- drifting – those who were drifting were “going with the flow” and didn’t have a plan and were not engaged in trying to learn more or be proactive about how to move forward.

The researchers also found that many people used more than one of these approaches over time.

It is tempting to expect that navigating, which is the most planful strategy, would be the most successful. However, the research found that this was not always the case. Sometimes being too committed to one path without yet knowing that much about it, or having had a chance to try it on, led to later not being as satisfied. In terms of the second strategy, exploring, the researchers found that young people sometimes faced criticism for exploring, but that exploring helped the interviewees understand their own identities and options better. Even drifting sometimes has positive outcomes when exposed by chance to positive experiences. The researchers conclude that all three approaches can be helpful and that an overreliance on believing that you should have an answer and decision can be detrimental.

“I think drifting and exploring for awhile and then navigating is cool. Kind of like getting thrown off a ship. You drift for awhile and then think this is getting a little boring so maybe I’ll swim this way for a little bit. Then you’re like, it’s definitely this way and you swim to shore.” Colin, a 26 year old from Halifax

(quote used with permission)

Young people reported that they faced great expectations for being planful. In our own work at a university career centre, we also hear students telling us that they receive a lot of the following messages, whether said explicitly, or implied:

- You should know where you want to go – you should make a decision

- It is better to know what you want to do than to not know

- The most successful people set and follow plans

The Decade After High School authors share the following visual (Figure 2.5) to illustrate the difference between expectations and reality and argue that “the results of this study highlight the importance of normalizing unpredictability and change in the school-to-work transition and providing young people with tools to work more effectively with this reality.” (Campbell & Dutton, 2015, p. 65)

What has your experience been? Do you feel pressure to have an answer and clearly laid out path? When someone asks you “What are you going to do after graduation? or “What are you going to do with your degree?” or “What do you want to be when you grow up?” – do you feel pressure to have an answer?

Planned Happenstance

When I was in my final year of undergrad, I was in my second floor apartment in downtown Toronto making lunch. I randomly decided to go over and look out the window and happened to see a friend of a friend walking on the street. I shouted out to him and we chatted for a few minutes and found out that he was looking for an apartment, and I was looking for a summer job. He ended up moving in to the apartment upstairs, and I ended up working at the same camp as he was, getting a foot in the door with the director by using his name. To this day we are still close, and the friends I made at that camp are still among my best. All because I looked out the window and said “Hi!”.

– Miguel Hahn, Chapter Co-Author

The themes identified in the Decade After High School research relate well to Planned Happenstance Theory. Mitchell, Levin, and Krumboltz (1999) argue that unexpected events play a significant role in most careers, and their Planned Happenstance model, an intentional oxymoron, is a good way to conceptualize how careers actually unfold.

We have spoken with countless professionals, often alumni of the universities where we have worked. When we’ve asked “how did you get to be where you are today?” there is a startling consistency to the answers. The number one response: “luck”. That is the “happenstance” part. But what about the “planned”? When we ask follow up questions about the luck, such as “When that lucky situation happened, how did you respond?”, we find that people actively took advantage of the luck to turn it into a career move. And when we ask questions like “And what had you done previously that put you in the situation where the luck was able to happen?” we find that people had had to have been actively engaged in a network and in exploration, in order to be somewhere where luck found them. Although the lucky happenstance was a key occurrence, each person had created the conditions for the luck, and then had acted on the luck rather than ignored it. These alumni stories map well into the Planned Happenstance framework.

There are two key tenets of planned happenstance theory (Mitchell et al., 1999, p. 118)

“a) exploration generates change opportunities for increasing quality of life; and

b) “skills enable people to seize opportunities.”

The first, that exploration creates opportunities, draws our attention to how we are not just passive recipients of chance events, but that we can increase the likelihood of positive happenstances through exploration and engagement. For example, individuals who have little to no interaction with the larger world are unlikely to experience a lot of exciting chance events that will bring new career opportunities. However, if we are engaged and connected, are building a strong network and attending events, speaking with colleagues, are part of an online community, and so on, then we are more likely to bump into new opportunities. Our own behaviours can generate greater likelihood for lucky opportunities. Then, when there is a lucky opportunity, we can choose to ignore it, or we can choose to take advantage of it. If there is a knock on the door we have to open it to see if it is a visit that might lead to something exciting.

Mitchell et al. (1999) lay out five skills that they believe help us generate and take advantage of happenstances, listed in the left hand column below. The interplay of these skills help us to make it more likely that we will have positive happenstances, and that we will then act on them in a way that leads to the most positive impact for our own lives.

Think of your own path so far, that has gotten you to today. What role has planning played, and what role has happenstance played?

| Curiosity: exploring new learning opportunities | How has curiosity led you to new opportunities in your past? |

| Persistence: exerting effort despite setbacks | What is an example of a time when you persisted and that meant that you were able to move forward despite facing challenges? |

| Flexibility: changing attitudes and circumstances | When in the past have you been flexible and that allowed you to take advantage of an opportunity you might not have had? |

| Optimism: viewing new opportunities as possible and attainable | How would you describe your own level of optimism and how much you believe new opportunities will appear and be things you can act on? |

| Risk taking: taking action in the face of uncertain outcomes | How would you describe your risk taking approach? What is an example of a time in the past when you took a risk on a new opportunity and it led to good things? |

(Adapted from Mitchell et al., 1999, p. 118)

The Chaos Theory of Careers

The Chaos Theory of Careers (Bright & Pryor, 2005; Pryor & Bright, 2014) has some commonality with Planned Happenstance (in particular the role of unexpected events), but is an attempt at a much broader new conceptualization of career development. The authors wanted a theory that would not just address how an individual makes a career decision, but one that also incorporates the complexity of variables, both personal and contextual, that impact career trajectories. They asked a fundamental, and very big, question: “Why should the influences on career development be different from those that brought about life or which shape our cosmos?” (Pryor & Bright, 2014, p. 4). They looked beyond the career development literature to general science and its attempts to explain the overall function of the natural world.

Careers, like other parts of nature, are part of a chaotic system: “An individual’s career development therefore is the interaction of one complex dynamical system (the person) with a series of more or less generalized other complex dynamical systems including other individuals, organizations, cultures, legislations and social contexts” (Pryor & Bright, 2014, p. 5).

The Chaos Theory of Careers uses terms from general Chaos Theory (such as complexity, non-linearity, chance and change), and applies them to career development.

Complexity – there are so many variables, linked in so many ways, that complexity is a reality of systems, including the systems within which we work and manage our careers. As covered in the labour market section, many authors are arguing that complexity is increasing and will continue to.

Non-linearity – Perhaps the most well-known component of general chaos theory is the butterfly effect, in which a butterfly flaps its wings in one part of the world, and impacts the weather somewhere on the other side of the globe. This is an example of non-linearity and, applied to careers as we have covered already, this emphasizes how most people’s careers do not follow a direct line, and that a small change can cause disproportionately significant impacts.

Chance – this theory reinforces the importance of recognizing how we cannot focus on predictability, but should recognize and even embrace the role of chance in our careers.

Change – the authors argue not only that there is constant change in the larger world, but that people themselves change. A criticism of the person-environment fit model (that we explored at the beginning of the section) is that it assumes little change in both the person and the environment. If people themselves are continually changing, how does that impact how people make career decisions?

The Chaos Theory of Careers draws our attention to the complexity of career development and to the multiple and often unpredictable influences on our options and opportunities.

How well do you think chaos describes the natural world? How well do you think a chaos theory can describe your career so far?

If careers are chaotic, how does that make your feel? Are you excited by the possibilities, concerned about the lack of predictability, intrigued by the complexity, or a combination of those feelings and/or others?

Constructivist Approaches

Much recent work on career development uses a constructive approach, emphasizing that reality, and how we experience it, are individually and socially constructed. There is not one objective reality, nor one story of who we are and our career path. A subset of constructivist theories, narrative approaches specifically highlight the role of story and argue that we narrate our own lives – “we are the stories that we live” (Niles & Harris-Bowlsbey, 2013, p. 113). As we tell the story of ourselves and our careers, we are designing our own reality. Although overall the world may be chaotic (should we ascribe to a Chaos Theory conceptualization), the narrative approach allows a look at how individuals have agency in impacting the stories they narrate for their own careers. It is “by constructing personal career narratives, we can come to see our movement through life more clearly and can understand our specific decisions with a greater life context that has meaning and coherence” (Niles & Harris-Bowlsbey, 2013, p. 112).

As an illustration of one constructivist approach, Savickas (1997) uses a “career story” process to help people narrate their own development. He asks clients five key questions about themselves – asking them to name role models, favorite magazines, favorite book, mottos and early recollections. Then, working together, the counsellor and client draw themes out of these reflections, and the client constructs a story of their career – identifying central themes that have guided them in the past, and that they may choose to use to guide them into the future. Having these themes then informs decision making about next steps.

Another example of a constructivist approach is the use of metaphor as a way for individuals to understand their own careers (Amundson, 2010). “People actively seek to make meaning of life events and this process is on-going” and metaphors are a common way humans make meaning (Amundson, 2010, p. 7). Using metaphors is helpful because by “referring to parallel examples where similar dynamics are in play” we are better able to understand a new experience by relating to the familiar metaphor (Amundson, 2010, p. 2).

Consider the following metaphors that might be used to describe your career:

| If you use this metaphor for your career,

• What does it bring to mind? |

|

| Career as journey, which can include getting a call, responding to the call, facing obstacles | |

| Career/life as a book – with chapters, difficult challenges, | |

| Climbing the ladder of success |

|

| Following the yellow brick road |

|

| Solving a puzzle (or many puzzles) |

|

| Undertaking a research project |

|

Metaphors adapted from Amundson (2010)

Limitations: Ethnocentricism

We have reviewed a few examples of how career development theory has evolved over time. During this evolution, there has been a growing conversation about diversity and the limitations of existing theories in an increasingly diverse community. Ethnocentrism is the assumption that one’s own “value system is superior and preferable to another” (Niles & Harris-Bowlsbey, 2013, p. 135). Historically most of the career development literature that is used in North America has been produced in North America, and primarily by members of dominant groups (Niles & Harris-Bowlsbey, 2013). It is important to note that these theories do not reflect a universal value system.

Arthur and Collins (2014) draw attention to several cultural assumptions that have been made in career development literature reflecting a European-American perspective:

- Individualism and autonomy – assuming that individuals make their own choices that create their futures

- Affluence – assuming that individuals have access to affluence, or the resources needed

- Structure of opportunity open to all- assuming that all individuals have access to opportunities

- Centrality of work in people’s live – assuming that work is a central part of lives

- Linearity, progressiveness, and rationality – assuming that individual’s careers progress in linear and rational ways

These assumptions, based on a “Western” worldview, limit the applicability of the career theories we have reviewed. Even the term “career” itself may have different meanings for different people, depending on historical and cultural influences (Arthur & Collins, 2014). Although the theories we are reviewing in this chapter all have useful ideas to offer, we should examine them through a lens of diversity and social justice, considering how each theory may be limited within a particular world view, and consider limits, biases, and gaps .

In addition to limitations within career theories, there are also limitations and structural barriers that people from marginalized groups may experience in the labour market. Niles and Harris-Bowlsbey (2013, p. 130) argue that “there is also ample evidence to suggest that women, people of colour, persons with disabilities, gay men, lesbian women, and transgender persons continue to encounter tremendous obstacles in their career development .”

Fortunately, there are increasingly more diverse voices in career development writings. Examples of recent work includes articles looking through an Indigenous lens (Caverley, Stewart, & Shepard, 2014), and considering the experiences of immigrants to Canada (Bylsma & Yohani, 2014) and of refugees to Canada (Sutherland & Ibrahim, 2014).

What messages about “career” have you learned from your family, and what messages are routed in your family’s history and experiences?

Are there any structural or systemic obstacles you believe you may (or have) experience as you pursue your career path? What privileges have you benefited from that have made your life easier?

Which, if any, of the assumptions listed above have you made when you think about careers and opportunities?

FINDING YOUR WAY– MOVING TOWARDS YOUR CAREER GOALS

In the previous section we reviewed the evolution of career development theory. We’re now going to present some more concrete processes and tools that you can use as you seek to develop your own career path and a meaningful sense of direction.

The Value of Purpose

Research from Harackiewicz, Barron, Tauer, and Elliot (2002) and Snyder et al. (2002) shows that students are more successful academically when they are motivated in pursuing career goals, with a desire to learn and embrace necessary challenges for growth, while students with undefined goals tend to put in minimal effort. Does this mean you have to have all the answers right now? Most definitely not – as we have said before, only some of us are in a position to be navigating directly towards a clear goal. However, taking active steps in exploring potential directions can give a sense of purpose to your time at university, help keep you motivated during challenging times, and position you for success during and after your studies.

This sense of purpose is different than a specific short-term goal – it is longer-term and broader – a direction we are always working towards that motivates and guides our decisions, often with a service component. Damon writes that purpose is “a part of one’s personal search for meaning, but also has an external component, the desire to make a difference in the world, to contribute to matters larger than the self” (Damon, Menon, & Bronk, 2003, p. 121).

Living purposefully requires knowing yourself to get clarity about what unique purpose is suited to you based on your unique personal makeup and identity. Having a sense of your values and interests is fundamental in terms of making decisions that align with who you are, but it is also important to factor in your strengths (Smith, 2017). In fact, research shows that when we use our strengths at work we are more likely to find meaning in our work, and to perform at a higher level (Dubreuil, Forest, & Courcy, 2014). In this section we will look at decision making strategies, self assessment strategies, key resources, and activities to help you get clarity as you think about your future options.

Making Career Decisions

Decision Making Styles

Everyone has their own style of making decisions – and the role of data plays a different role in each style. Dinklage found 8 decision making styles (1968):

- Planful – systematic process with goals, options, and actions

- Agonizing – Try to be planful, but end up excessively focusing on data and information to their detriment and struggle to make a perfect decision

- Impulsive – select alternative quickly, minimal use of data

- Intuitive – Use experience and judgment to decide on path with little use for data

- Compliant – highly influenced by other opinions or social norms

- Delaying – Sees a decision to be made but avoids it – lacking motivation or information

- Fatalistic – Feels their actions don’t matter, that decision is out of their hands

- Paralytic – Sees decision, but is paralyzed by fear of process or outcome

Having a sense of your own decision making style can help you to navigate your own ongoing career decision.

When have you made big decisions in the past?

Were you successful? Why? Why not?

What do you need to do differently the next time?

Decision Making Processes

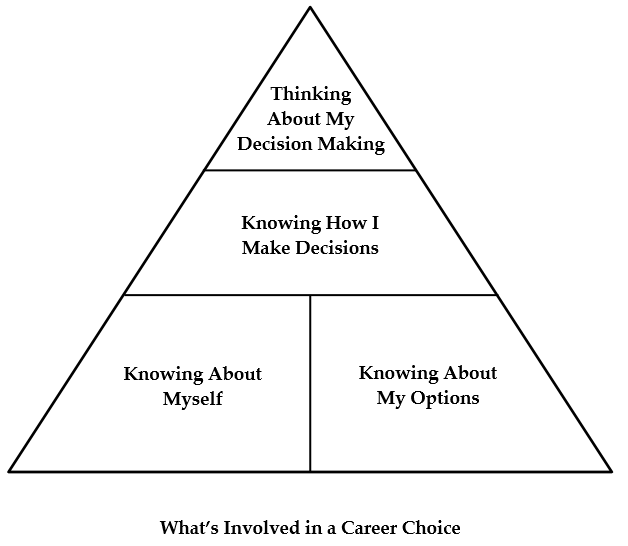

The Cognitive Information Processing Approach examines how we make effective career decisions (Sampson, Peterson, Lenz, & Reardon, 1992). It posits that decisions involve both cognitive and affective elements, and that career decisions are ongoing, with our knowledge evolving over time. In their information processing pyramid (Figure 2.6) they describe 3 foundational components: self-knowledge, occupational knowledge, and decision-making skills, capped by metacognition (awareness of our thoughts and processes). We will work through these pieces in the coming sections exploring self-assessment, exploring options, and decision making.

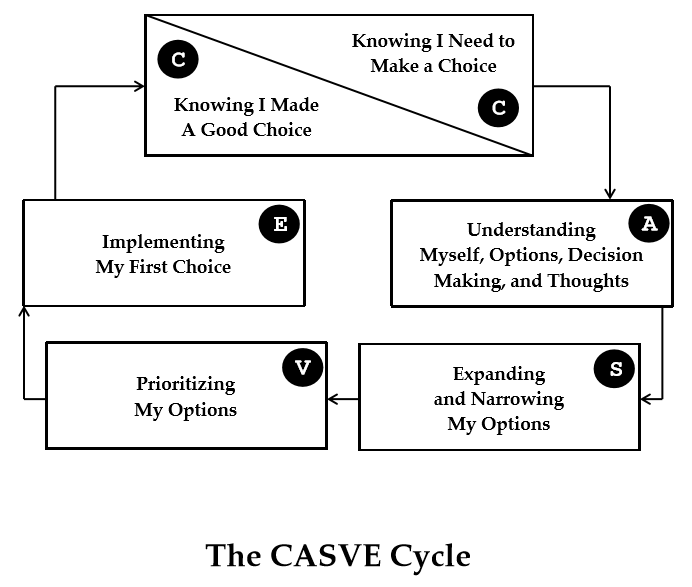

The Cognitive Information Processing Approach also includes the CASVE process (named after the phases of Communication, Analysis, Synthesis, Valuing, and Execution) featured below which explains the phases we go through in making a decision. The first two components from the pyramid are incorporated into the analysis phase, while the metacognition and decision-making skills apply throughout. The process reflects the cyclical nature of navigating career decisions, as we incorporate new learning and experiences into future decisions.

Figure 2.7. CASVE Model

By paying attention to your own thought process you can monitor your progress. Are you in need of more information or options? Or do you need to move ahead with evaluation and execution and learning from your experiences? Although not everyone is the same place, it is very common for university students to benefit from attention to all aspects of this process – starting with analysis of self and options. In the coming sections we will look at the various phases of the CASVE model of decision making to help you make informed career decisions.

Analysis Part 1 – Self-assessment

While most students want to start with the question “what can I do with my degree?” – most career counsellors will try to shift the initial conversation to learning more about you as a person. Your unique makeup in terms of personality, skills, values, interests, experiences, connections, and your environment will all greatly influence career directions that you might choose to pursue. As students of psychology you are well aware there are many ways to try to measure and assess people – from complex formal assessment tools, to mind-mapping, journaling, and reflective conversation – and they can all contribute different pieces to your evolving self-understanding.

Using Assessment Tools

Commonly Used Personality and Career Assessments

| Assessment | Description | Availability |

| Six Factor Personality Questionnaire | Based on Big Five research, measures personality traits of Agreeableness, Neuroticism, Openness to Experience, Extroversion, and splits Conscientiousness into Industriousness and Methodicalness.

Read more about psychometric properties at: |

Assessment professional. |

| Strong Interest Inventory | Explores work interest areas divided into Holland’s RIASEC categories of realistic, investigative, social, enterprising, and conventional.

Read more about psychometric properties at: |

Assessment professional. |

| VIA Character Strengths | Based on Seligman’s Positive Psychology, focuses on assessing character strengths.

Access the free test online at: |

Free |

| Strengths Finder 2.0 | Based on Clifton’s work with Strengths Psychology.

Access the test online (for fee, or with book purchase) at: |

Purchase online or with book. |

| Life Values Inventory | Helps you clarify your personal values to make more effective decisions.

Access for free at: |

Free |

Assessment by Self-Reflection

A number of popular career books outline reflection activities to help you make sense of your current career situation, often partly involving looking backwards at past experiences, or collecting data from current experiences. In our work with students we have found a few to be particularly useful:

| Activity | Instructions |

| Mind-mapping – a creative open-ended way of pouring out ideas to mine your experience for insights | Start with a large blank piece of paper, and write your name in the middle. Then, radiating outwards, write our any idea that comes into your head as potentially relevant for your future – it could include past jobs, hobbies, mentors, strengths, fears, dreams, etc… |

| Journaling – to track daily experiences of engagement | Start paying attention to your daily experiences and record how each activity went in terms of your subjective experience – what you enjoyed, did well, or disliked. |

| Experience reflections – a variety of exercises for personal clarification | Write down key career stories from your past where things were going well – and reflecting on the meaning in terms of skills, interests, or values for you personally. |

For more ideas and reflective activities you may want to consult a career planning book like some of these popular titles students have enjoyed in the past:

- You Majored in What?, Katharine Brooks, Ed. D.(2010)

- Designing Your Life, Bill Burnett & Dave Evans (2018)

- What Colour is Your Parachute?, Richard Nelson Bolles (2018)

- Business Model You, Tim Clark (Clarke, Osterwalder, & Pigneur, 2012)

Assessment through other’s perspectives and support

Another rich source of information about ourselves can be other people around us. Family, friends, coworkers, supervisors or teachers could all offer perspectives that can complement your own internal reflection or results from formal assessments. You can ask important people (between 5-10) who know you well for their perspective on your key strengths, weaknesses, or personal qualities.

Finally, you may want to consider getting help with the self-assessment process by talking to a professional career counsellor. Most university’s have some form of career centre on campus that provides career advising or counselling to students. Career counsellors are trained to guide you through the process of reflecting on yourself, exploring possibilities, and making plans to move towards your goals. Often, having a conversation with an unbiased person who doesn’t know you personally can help you get clarity and perspective on your situation to help you feel more confident in knowing what directions are personally meaningful to you.

Learning about oneself is not a one-time event, but rather an ongoing process that unfolds over our lifetime. Not only do we come to understand ourselves in deeper ways, but we also continue to change and evolve from our experiences – meaning that a situation that might be a good fit for us in our twenties, could not be as good of a fit in our thirties or forties.

Analysis Part 2 – Exploring Career Options

This book is an excellent starting point for exploring your career options related to psychology – it will provide a solid overview of some of the most common pathways you might want to consider, as well as some new ideas you hadn’t thought of before.

Formal sources of information

To take this research further, and explore possibilities not covered here you may want to consult other sources of career information such as:

- Job Bank (Government of Canada, 2018d) – to access information on wages, outlooks, education, skills, and more. https://www.jobbank.gc.ca/explorecareers

- O*NET (U.S. Department of Labor, 2018) – a similar website to Job Bank from the United States https://www.onetonline.org/

- Career Cruising (2018)– an informative Canadian resource with information on thousands of careers covering education programs, related careers, interviews with professionals, and more. May be available through your campus career centre.

- LinkedIn (LinkedIn Corporation, 2018) – similar to Facebook in terms of profiles and newsfeed, but offers a powerful search tool including the ability to search alumni by institution to see what others have done with your degree.

- Career books – Your campus career centre may have a resource library featuring books with occupational information that can help you go more in-depth in areas of interest

- Professional Associations – most occupations have a professional association (for example NAADAC, The Association for Addiction Professionals, or CAOT, The Canadian Association for Occupational Therapists, exist for most professions. They can be a source of valuable information on a career of interest, including links to further education, job opportunities, conferences, certification, and more.

Informal sources of information

Speaking to professionals working in areas of interest can be a valuable source of insight (known as information interviewing). They can answer questions about a typical day, challenges, rewards, required qualifications, strategies for entering the field, and provide advice for your unique situation. To find people to speak to, ask people in your network if they know anyone working in the field, seek out alumni from your school, or connect with professional associations.

Questions you could ask in an information interview:

- What interests keep you going in your work?

- What skills are essential in doing your work?

- What are your work/life fit preferences (values and needs) that are met in this work?

- If you were going to start again in this field of work today, what would you do to be really ready? (What training and experience would you need to have? What would be great ways to get it?)

- What professional associations do you rely on to keep up to date? What publications, organizations or people do you suggest I contact for more information?

Synthesis and Valuing

As you collect information on yourself and careers, you will be moving into the next phase of the CASVE model, of synthesizing options and valuing potential directions based on the information you found which helps you move into the execution phase of testing out your ideas.

If your research does not provide an obvious career direction to explore, it may help to work through more systematic analyses of your findings. This can be as simple as a chart of pro’s and con’s for each career of interest to help you get a more holistic view of each option. For a more in-depth analysis, consider using a matrix to rank the options against a set of important criteria. For example – someone might analyze 3 career paths of psychologist, marketing professional, and lawyer, and explore them in terms of pay, satisfaction, creativity, status, and investment required in training.

Alternatively, you might benefit from talking through your various options with family, friends, or seeking professional help from an impartial career counsellor to help you clarify your thoughts and feelings.

Execution and Taking Action

Although collecting and analyzing information is very useful, it is important to balance research with action and experience. By testing out your career ideas, you can get very important firsthand experience that can tell you more about your potential career directions. Planned Happenstance and Chaos Theory tell us of the impossibility of knowing the future in great detail, and the value of taking action despite this. As you move forward gaining various experiences from coursework, extra-curricular activities, part-time work, volunteering, and otherwise – you will likely learn new information about yourself and the world of work that could inform and maybe alter your career direction.

As you move forward learning from your coursework and other experiences, you will also be developing marketable experience that will be valuable in future applications to work or graduate school. While initially pursuing a broad range of experiences can be beneficial, at a certain point, starting to focus on a few specific directions will likely help you be more strategic in your involvement. Considering what you have learned in the research stage about careers of interest can help you prioritize the development of key skills to help you pursue the well-rounded education needed to be successful in your next step.

The Value of Ongoing Reflection

To get the most of your time at university, it is important to complement your education and experiences with ongoing reflection. In fact, a recent study showed that employees who reflected for 15 minutes daily performed 23% better at their work after 10 days than employees who didn’t participate in the reflection (Di Stefano, Gino, Pisano, & Staats, 2014).

Not only does ongoing reflection reinforce your learning and inform decisions, it will also help you when it comes time to apply to jobs or school as it will help you to articulate the value of your experience and skills to potential employers or graduate programs. You may want to consider some key questions after or during new learning experiences such as courses, extracurricular activities, or work:

- What was challenging about this experience? How did I overcome it? What results did I achieve?

- What impact did I have on those around me, on my environment, or on myself?

- How did this change me? What do I do or see differently now?

- What is most significant this experience for me? For a potential employer?

- What areas of growth does it show for me? What skills did I develop?

Likewise, we encourage you to reflect on your learning throughout this course. As you learn about various possible career paths, connect them back to your personal experiences and what you are learning about yourself. Are they a good fit? Why or why not? What is this telling you about what you want or where you want to go?

Chapter Summary

In this chapter we’ve covered the following key ideas as you think about how to make sense of the information of this book and apply it to your own career decision making.

The value of your degree: Your Psychology degree can help to prepare you to head in many potential career directions. To position yourself for success, be able to articulate the value of your degree to future employers and grad programs with a clear sense of the skills and knowledge you have gained, and add to this with experience outside of the classroom.

Making sense of labour market information: Integrating knowledge of opportunities and labour market trends with an understanding of yourself can help you make more informed decisions now and in the future.

Consider person-environment fit: but remember it is only part of the equation.

Accept & embrace chance and chaos: chance and unpredictability are normal. In addition to planning, embrace happenstance – success derives from a combination of planning, preparedness, and taking advantage of luck. Use the five skills outlined by Krumboltz, Mitchell, and Levin (1999):

- Curiosity: exploring new learning opportunities

- Persistence: exerting effort despite setbacks

- Flexibility: changing attitudes and circumstances

- Optimism: viewing new opportunities as possible and attainable

- Risk taking: taking action in the face of uncertain outcomes

Actively explore possibilities: Proactively exploring careers of interest can give you a sense of direction, ease anxiety, and motivate you to do your best academically.

Get to know yourself: Through formal and informal means, developing a sense of you are in terms of strengths, values, interests, and personality can help you make better decisions and articulate your value to potential employers or graduate school admission committees.

Access resources: gather information and support with online tools, people in your network, and resources at your university career centre.

References

American Psychological Association. (2013). APA guidelines for the undergraduate psychology major: Version 2.0. Retrieved from American Psychological Association website: http://www.apa.org/ed/precollege/undergrad/index.aspx

Amundson, N. E. (2010). Metaphor Making: Your career, your life, your way. Richmond, BC: Ergon Communications

Arthur, N., & Collins, S. (2014). Diversity and social justice: Guiding concepts for career development practice. In B. C. Shepard, & P. S. Mani (Eds.),Career development practice in Canada (pp. 77-104). Toronto, ON: Canadian Education and Research Institute for Counselling.

Asplund, J., Agrawal, S., Hodges, T., Harter, J., & Lopez, S. J. (2014) The Clifton Strengthsfinder 2.0 technical report. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/267694228_THE_CLIFTON_STRENGTHSFINDER_R_20_TECHNICAL_REPORT

Bostan, A. (2009). Globalization and instability on financial markets. Economy Transdisciplinarity Cognition, (1), 167-171. Retrieved from http://www.ugb.ro/etc/etc2009no1/S0602%20(2).pdf

Bright, J. E., & Pryor, R. G. (2005). The chaos theory of careers: A users guide. The Career Development Quarterly, 53(4), 291-305. doi:10.1002/j.2161-0045.2005.tb00660.x

Brooks, K (2010) You majored in what? Designing your path from college to career. New York City, NY: Plume.

Brown, D., & Crace, R. K. (2002). Life values inventory facilitator’s guide. Williamsburg, Virginia: Applied Psychology Resources, Inc.. Retrieved from http://www.lifevaluesinventory.org/LifeValuesInventory.org%20-%20Facilitators%20Guide%20Sample.pdf

Burnett, B., & Evans, D. (2018) The designing your life workbook: A framework for building a life you can thrive in. Danvers, MA: Potter/Ten Speed/Harmony/Rodale.

Business Council of Canada (2018). Navigating change. Retrieved from Business Council of Canada website: https://thebusinesscouncil.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/Navigating-Change-2018-Skills-Survey-1.pdf

Bylsma, L., & Yohani, S. C. (2014). Immigrants in Canada: Context and issues for consideration in career development practice in Canada. In B. C. Shepard, & P. S. Mani (Eds.) Career development practice in Canada: Perspectives, principles, and professionalism (pp. 249-274). Toronto, ON: Canadian Education and Research Institute for Counselling.

Campbell, C., & Dutton, P. (2015). Career crafting the decade after high school: Professional’s guide. Toronto, ON: Canadian Education and Research Institute for Counselling.

Career Cruising (2018) Career Cruising [Homepage]. Retrieved from https://public.careercruising.com/en/

Caverley, N., Stewart, S., & Shepard, B. C. (2014). Through an Aboriginal lens: Exploring career development and planning in Canada. In B. C. Shepard, & P. S. Mani (Eds.) Career development practice in Canada: Perspectives, principles, and professionalism (pp. 297-330). Toronto, ON: Canadian Education and Research Institute for Counselling.

Clark, T., Osterwalder, A., & Pigneur, Y. (2012). Business model you. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Council of Ontario Universities (2016). Grad Survey. Retrieved from Council of Ontario Universities website: http://cou.on.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/COU-Grad-Survey-2016.pdf

Damon, W., Menon, J., & Bronk, K. C. (2003). The development of purpose during adolescence. Applied Developmental Science, 7(3), 119-128. doi:10.1207/s1532480xads0703_2

Di Stefano, G. D., Gino, F., Pisano, G. P., & Staats, B. R. (2014). Learning by thinking: How reflection aids performance. SSRN Electronic Journal. doi:10.2139/ssrn.2414478

Dinklage, L. B. (1968). Decision strategies of adolescents (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University.

Dubreuil, P. Forest, J., & Courcy, F. (2014). From strengths use to work performance: The role of harmonious passion, subjective vitality, and concentration. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 9, 335-349.

Fraser Institute (2015) An analysis of public and private sector employment trends in Canada, 1990-2013. Vancouver, British Columbia: Author. Retrieved from https://www.fraserinstitute.org/sites/default/files/analysis-of-public-and-private-sector-employment-trends-in-canada.pdf

Gallup, Inc. (2018). CliftonStrengths [Webpage]. Retrieved from https://www.gallupstrengthscenter.com/home/en-us/strengthsfinder

Gottfredson, L. S. (1996). Gottfredson’s theory of circumscription and compromise. In D. Brown & L. Brooks (Eds.), Career choice and development (pp. 179-232). San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass

Government of Canada (2016). Key small business statistics. Retrieved from http://www.ic.gc.ca/eic/site/061.nsf/eng/h_03018.html

Government of Canada (2018a). Career tool report: Psychology, Bachelor’s degree. Retrieved from: https://www.jobbank.gc.ca/studentdashboard/FOS20708/LOS05

Government of Canada (2018b). Career tool report: Psychology, Master’s degree. Retrieved from https://www.jobbank.gc.ca/studentdashboard/FOS20708/LOS07

Government of Canada (2018c). Labour market facts and figures: Psychologists in Canada. Retrieved from https://www.jobbank.gc.ca/marketreport/outlook-occupation/2218/ca

Government of Canada (2018d). Labour market information. Retrieved from https://www.jobbank.gc.ca/explorecareers

Gratton, L. (2011). The shift: The future of work is already here. London, UK: HarperCollins.

Harackiewicz, J. M., Barron, K. E., Tauer, J. M., & Elliot, A. J. (2002). Predicting success in college: A longitudinal study of achievement goals and ability measures as predictors of interest and performance from freshman year through graduation. Journal of Educational Psychology, 94, 562-575.

Jackson, D. N, Paunonen, S. V., & Tremblay, P. F. (2000) Six factor personality questionnaire [Webpage]. Retrieved from https://www.sigmaassessmentsystems.com/assessments/six-factor-personality-questionnaire/

Life Values Inventory Online. (2018). Life Values Inventory [Homepage]. Retrieved from http://www.lifevaluesinventory.org/

LinkedIn Corporation (2018). LinkedIn [Homepage]. Retrieved from https://ca.linkedin.com/

Mitchell, K. E., Levin, A. S., & Krumboltz, J.D. (1999) Planned happenstance: Constructing unexpected career opportunities. Journal of Counseling & Development, 77, 115-124.

Neault, R. A. (2014) Theoretical foundations of career development. In B. C. Shepard, & P. S. Mani (Eds.) Career development practice in Canada: Perspectives, principles, and professionalism (pp. 129-150). Toronto, ON: Canadian Education and Research Institute for Counselling.

Nelson Bolles, R. (2018) What Colour is Your Parachute? Danvers, MA: Ten Speed Press.

Niles, S. G., & Harris-Bowlsbey, J. (2013) Career development interventions in the 21st Century. (4th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson.

Pryor, R. G, & Bright, J. (2003). The Chaos Theory of Careers. Australian Journal of Career Development, 12(3), 12-20.

Pryor, R. G, & Bright, J. (2014). The Chaos Theory of Careers (CTC): Ten years on and only just begun. Australian Journal of Career Development, 23(1), 4–12.

Rajecki, D. W., & Anderson, S. L. (2004). Career pathway information in introductory psychology textbooks. Teaching of Psychology, 31, 116-118.

Sampson, J. P., Jr., Peterson, G. W., Lenz, J. G., & Reardon, R. C. (1992). A cognitive approach to career services: Translating concepts into practice. Career Development Quarterly, 41, 67-74.

Savickas, M. L. (1997). Career Counseling. Washington, DC.: American Psychological Association.

Smith, E. E. (2017). The power of meaning: Crafting a life that matters. London, UK: Rider Books.

Snyder, C. R., Shorey, H. S., Cheavens, J., Pulvers, K. M., Addams, V. H., & Wiklund, C. (2002). Hope and academic success in college. Journal of Educational Psychology, 94, 820-826.

Statistics Canada (2005) Highlights of the national survey of non-profit and voluntary organizations (Catalogue No. 61-533-XIE). Retrieved from http://publications.gc.ca/collections/Collection/Statcan/61-533-XIE/61-533-XIE2004001.pdf

Sutherland, S., & Ibrahim, H. (2014) Refugees in Canada: From persecution to preparedness. In B. C. Shepard,, & P. S. Mani (Eds.) Career development practice in Canada: Perspectives, principles, and professionalism (pp. 275-296). Toronto, ON: Canadian Education and Research Institute for Counselling.

The Myers-Brigg’s Company. (2018). Validity of the Strong Interest Inventory® Instrument [Webpage]. Retrieved from https://www.cpp.com/en-US/Support/Validity-of-the-Strong-Interest-Inventory

U.S. Department of Labor (2018) One Net Online [Homepage] Retrieved from https://www.onetonline.org/

U.S. National Center for Education Statistics. (2017). Early millennials: The sophomore class of 2002 a decade later (NCES 2017-437). Retrieved from https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2017/2017437.pdf

VIA Institute on Character. (2018). Join the over 7 million people [Homepage]. Retrieved from https://www.viacharacter.org/www

VIA Institute on Character. (2018). VIA Assessments Psychometrics [Webpage]. Retrieved from https://www.viacharacter.org/www/VIA-Assessments-Psychometrics#

Please reference this chapter as:

Keates, C., & Hahn M. (2019). Introduction to career development. In M. E. Norris (Ed.), The Canadian Handbook for Careers in Psychological Science. Kingston, ON: eCampus Ontario. Licensed under CC BY NC 4.0. Retrieved from https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/psychologycareers/chapter/career-development/