14 Applications and careers in community psychology: Practicing in settings, systems, and communities to build well-being and promote social justice

Liesette Brunson, Ph.D., Associate Professor, Département de psychologie, Université du Québec à Montréal

Alexis Gilmer, M.A., Doctoral Candidate, School Of Public Health And Health Systems, University of Waterloo and Department of Psychology, Wilfrid Laurier University

Colleen Loomis, Associate Professor, Balsillie School of International Affairs and Wilfrid Laurier University

Community psychology (CP) bases its action on the recognition that individuals’ development, psychological functioning, and mental health are profoundly affected by their physical, social, cultural, political, and economic contexts (Hakim, 2010, Jason & O’Brien, 2018; McMahon, Jimenez, Bond, Wolfe, & Ratcliffe, 2015; Wolff, 2014). This chapter presents CP applications and careers in two sections. The first section provides an overview of important areas of intervention and practice in CP, starting with a brief history of the field, an introduction to its typical research methods, and highlights of significant scholarly findings. The second section presents a model of CP practice and describes career and training opportunities in CP.

Introduction to Community Psychology[1]

What is Community Psychology?

CP is concerned with individuals and their immediate interpersonal context and links their well-being to broader social structures and dynamics (Arcidiacono 2017; Moane, 2003). Rooted in a scientific and empirical approach to understanding the world, CP uses the research process as well as scientific knowledge and intervention strategies to create social change and improve well‐being at the individual, organizational, and community levels (Neigher, Ratcliffe, Wolff, Elias, & Hakim, 2011). CP draws attention to the importance of diversity, inclusion, and economic and social equity and highlights the power of preventing problems as well as treating them (Julian, 2006; Wolff et al., 2017). CP contributes to psychology in general by proposing a critical analysis of the social context that affects human well-being and highlighting the importance of working in partnership with the people most affected by social problems. Community psychologists analyse and intervene at the interface between individual and social factors, focus on complexity and systems, and hold prevention, advocacy, social justice, and systems change as core concerns (Arcidiacono, 2017; Dzidic, Breen & Bishop, 2013; Evans, Duckett, Lawthorn, & Kivell, 2017; Prilletensky, 1997; Rappaport, 1981).

Although the emphasis on social contexts is not unique to the discipline, CP is ultimately concerned about the effects of social context on human well-being, development and functioning, rather than on describing social and cultural systems for their own sake. CP is also distinguished by theoretical frameworks that emphasize aspects often neglected in more individualized approaches to human problems (Jason, Stevens, Ram, Miller, Beasley, & Gleason, 2016; Stein, 2007), such as ecological analysis (Bronfenbrenner, 1979; Hawe, 2017; Kelly, 1986; Neal, 2016), historical-material analysis (Montero, Sonn, & Burton, 2017), and social determinants of health (Montero, 2012). Certain values-based frames of analysis also tend to characterise the field and nourish its practice (Evans et al., 2017; Montero et al., 2017; Rappaport, 1981; Wolff et al., 2017). Diverse as they are, these theoretical and value-based frames of analysis provide conceptual tools for understanding social actors, their activities and positionality, and the patterns and determinants of constraints and opportunities that surround them and shape their possibilities.

Thus, the distinctive nature of CP is probably best characterised in terms of its unique constellation of principles, goals and values, frames of analysis, and methods for change. While the particular constellation and composition of these elements varies across countries and cultures (Francescato & Zani, 2013; Lykes, Terreblanche, & Hamber, 2013; Wolfe, Scott & Jimenez, 2013), community psychologists globally are unified by the goal of promoting well-being by working at the interface between people and their social contexts.

A Brief History of Community Psychology

CP emerged as a discipline across the globe throughout the mid-1900s, largely in response to political turmoil, skepticism regarding the dominant views of psychology, movements for social change, and a transformation of the mental health care system in many countries (Nelson, Lavoie, & Mitchell, 2007). Though in some countries CP is still relatively emergent, other regions have seen immense growth and development in the field since the 1970s (Reich, Riemer, Prilleltensky, & Montero, 2007).

In Canada, events that led to the emergence of CP include the community health movement, alternatives to institutionalization, and a focus on prevention (Nelson, et al., 2007). Though the birth of the field of CP is often linked to the 1965 Swampscott Conference in the U.S., Pols (2000) links the birth of Canadian CP to the mid-1920s and Edward Bott, the first chair of the psychology department at the University of Toronto, who with William Line and colleagues developed school- and community-based prevention projects (Nelson, Ochocka, Janzen, Trainor, Goering, & Lomoteyet al., 2007). Line was the first to use the term community psychology while discussing primary prevention in the 1951 Royal Commission Report (Babarik, 1979). In the 1970s and 1980s, CP programs were established in several Canadian universities. Wilfrid Laurier University and the Université du Québec à Montréal started the first Canadian masters and doctoral programs, respectively, and the University of Manitoba assembled a national CP network, which led to the creation of the CP section of the Canadian Psychological Association in 1982 (Nelson, et al., 2007). In that same year, the Canadian Journal of Community Mental Health was created and allowed for interdisciplinary communication and cooperation concerning the promotion of community mental health (Walsh-Bowers, 1998). In the early 2000s, doctoral programs were developed at Laval University and Wilfrid Laurier University, further expanding the field in the academic realm (Aubry, Sylvestre, & Ecker, 2010). A wide range of focus areas is studied within CP, with recent social issues within the Canadian context demanding attention, such as the increasing demand for mental health services, integration for newcomers to Canada, housing security, and the social dismissal of Indigenous peoples (Nelson & Aubry, 2010).

Methods in Community Psychology

Research methods in CP are both similar to and different from other fields such as social, clinical, and developmental psychology. Research is conducted using quasi-experimental, correlational, qualitative and longitudinal studies with interviews, self- or other surveys, reports, and observations. CP also uses case study, ethnographic, and phenomenological methods typical of disciplines such as sociology, economics, political science, and public health. Given that psychology students are typically introduced to the analysis of quantitative data early in their studies, many CP instructors emphasise qualitative and mixed methods in order to prepare students for the varied research approaches that are used to accomplish the twin goals of action and research. To conduct action-oriented research, additional methods include program evaluation, assets and needs assessment, and community-based participatory action research (CBPAR). CBPAR, for example, is a collaborative approach to research that involves community members directly affected by the problem being studied in all phases of a research project, from the definition of the initial research questions to the analysis of data, development of recommendations and diffusion of results. CBPAR begins from the concerns expressed by a particular community and uses research to support changes desired by the community (Burns, Cook, & Schweidler, 2011). These change-oriented research strategies realize the call by Martín-Baró for psychology research to reveal what “needs to be done” (1994, p. 6) by researching the process of change. Although there are many ways to examine change, the key to community research is to investigate how a community-driven effort impacts what that community has decided needs to be changed.

The choice of appropriate methods to be used in CP depends on the research questions and the researcher’s knowledge of many methods as well as personal values. As Campbell (2010) pointed out, when methods drive the research process, the questions must fit within the boundaries of what the method can address. However, when the research questions drive the research process, methods can be selected, modified or combined based on their ability to provide answers. Community psychologists need to be well-informed about various methodological options in order to avoid letting the method drive the question. Campbell concludes by reminding us, “By letting our research questions develop without the constraints of methods, and by allowing our values to have a voice in the research process, we can figure out what is right – for a given context” (Campbell, pp. 308-310).

A critical part of community research is developing the ability to communicate in multiple ways to different audiences to stimulate change. Methods for sharing research findings include oral presentations to research participants and professionals at conferences, publications in academic journals, reporting in policy briefs, workshops, interactive websites, and other interactive methods of knowledge exchange. Researchers have also developed and tested a method for evaluating the impact of knowledge mobilisation efforts (e.g., Hayward, Loomis, Nelson, Pancer, & Peters, 2011; Worton, Loomis, Pancer, Nelson, & Peters, 2017).

Significant Scholarly Findings

CP has contributed a number of significant findings to psychology and social science knowledge and practice; a comprehensive overview is available in Bond, Serrano-Garcia, Keys, and Shinn (2017a, 2017b). Here we highlight CP’s contributions to two significant research and practice movements: the community mental health movement and the current focus on prevention and health promotion.

Community mental health.

Until the mid-1900s, many individuals with mental illnesses were confined to psychiatric hospitals that were typically ineffective, dehumanizing, and unsanitary (Nelson, Kloos, & Ornelas, 2014). The deinstitutionalization movement within Canada began in the 1960s, resulting from limited funding for psychiatric hospitals as well as growing pressure for human rights and effective treatment within the community (Nelson, 2006). This movement led to many previously institutionalized individuals being released into the community even though few services were available to support individuals through this transition (Nelson, et al., 2014). Many of these individuals faced additional stressors upon release from psychiatric institutions, including unemployment, homelessness, poverty, discrimination, social isolation and a lack of psychosocial support, thus illustrating how mental illness often occurred in combination with other social issues not necessarily addressed by typical psychiatric treatment (Nelson, Kloos, & Ornelas). Deinstitutionalization forced a shift in focus from the institutional-medical model to a community treatment approach. This shift resulted in the emergence of alternatives to psychiatric hospitalization (e.g., assertive community treatment, supportive housing, healing lodges, case management) and alternative types and views of support, such as consumer/survivor initiatives, and self-help groups (Nelson, Lord, & Ochoka, 2001).

This drastic change in mental health reform created a movement towards community mental health. Community mental health aligns with core CP values in examining the social, economic, and cultural factors influencing and maintaining mental illness (Fortin-Pellerin, Pouliot-Lapointe, Thibodeau, & Gagne, 2007). Community psychologists have continued to work in community settings to improve well-being and mental health among populations since the overhaul of psychiatric institutions in the mid-1900s. For example, Canada was the first country to hold a self-help conference (Lavoie, Borkman, & Gidron, 1992). Just over a decade later, a longitudinal participatory action research evaluation of consumer-run self-help organizations found significant reductions of symptom distress, and significant improvements in quality of life, community integration, and employment among members of the self-help organizations compared to non-members (Nelson, Ochocka, et al., 2007).

Extensive research supports the adoption of the Pathways to Housing First (HF) model in the At Home/Chez Soi demonstration project as one of the most remarkable and effective community mental health initiatives in Canada (Tsemberis, 1999; Tsemberis, Gulcur, & Nakae, 2004) . For individuals with a mental health diagnosis who are experiencing homelessness, At Home provides housing first and treatment second, rather than the inverse order that was ineffective in improving well-being (Aubry et al., 2016). The HF model involves providing choice over housing options, allowing a sense of agency and independence to participants, who are often referred to as consumers rather than clients to emphasise their agentic role in relation to their housing transitions (Nelson, Stefancic, et al., 2014). Individuals with serious mental illnesses experience unstable housing at a more prevailing rate than those without mental illness; thus, neighbourhood and housing environments are particularly important for this sample of the population (Kloos & Shah, 2009). Promising findings have emerged from evaluations of At Home/Chez Soi, including longer times spent in stable housing and higher ratings of quality of housing among individuals assigned to HF compared to participants in the treatment-as-usual condition, who had access to existing housing and support services within their communities (Aubry et al., 2016). Additionally, participants in the HF condition reported a higher quality of life and were assessed as having better community functioning than the treatment-as-usual condition (Aubry et al.). Further, participants receiving HF with previous criminal activity have shown a more significant reduction in new criminal offences post-intervention in comparison to those in the treatment as usual condition (Somers, Rezansoff, Moniruzzaman, Palepu, & Patterson, 2013).

Prevention and promotion.

CP has contributed significantly to highlighting the importance of prevention and health promotion as a complement to treatment. Caplan (1961) highlighted three types of prevention. Primary (universal) prevention targets entire populations to lower the rates of new cases of disorders; secondary (selective) prevention targets populations at risk of developing a disease or disorder, and tertiary (indicated) prevention targets populations who already have a disorder and focuses on lowering the intensity or duration of the disorder. Dramatic increases in prevention awareness and efforts have taken place since the 1960s (Dalton, Elias, & Wandersman, 2007). Although prevention infuses and informs a number of disciplines, many authors highlight the contributions of early community psychologists to applying public health approaches to physical health to promoting the importance of a prevention focus in mental health.

One prevention program in Canada is Better Beginnings, Better Futures (BBBF), a research demonstration project for children and their families in disadvantaged communities. BBBF was initiated by the Ontario provincial government to address the limitations of other early childhood programming including a narrow focus on the child with little to no regard for the impact of familial and community contexts (Gottlieb & Russell, 1989). BBBF engages residents in the creation and implementation of programs to address specific community needs to achieve three overarching goals: the promotion of well-being and healthy child development, the prevention of developmental problems, and the promotion of community development (Gottlieb & Russell). Evaluation research has shown significant changes in children, families, and communities. For example, at grade 12, youth who participated in BBBF had higher average grades, a higher proportion of involvement in regular exercise, and a lower proportion of special education service use, and lower rates of criminal behaviours than the comparison communities (Peters, et al., 2010). At the community level, significant improvements were seen in parental involvement in neighbourhood activities, greater use of both health and social services within the community, a strong sense of community involvement, neighbourhood satisfaction, and neighbourhood cohesion within the BBBF intervention group (Pancer, Nelson, Hasford, & Loomis, 2012), and greater neighbourhood attachment (Hasford, Loomis, Nelson, & Pancer, 2013). Cost-savings analysis indicated a return of $2.50 CDN for every $1.00 CDN the provincial government invested, mostly due to decreased use of special education services, social assistance, and disability support programming (Peters, et al., 2016).

Another significant prevention program involved the emergence of the first safer injection facility (SIF) in North America, Insite, located in Vancouver, BC (Kerr, MacPherson, & Wood, 2008). SIFs allow space for injection drug users to use pre-obtained illicit drugs in the presence of healthcare staff who may intervene in the case of overdose (Kerr et al.). Insite opened in September 2003, mainly in response to the HIV epidemic and increasing rates of overdose appearing in the downtown east side of Vancouver (Kerr et al.). In response to community concerns regarding the risk of increased drug activity and drug-related crime upon the opening of Insite, Wood, Tyndall, Lai, Montanero, and Kerr (2006) conducted a study. They examined crime rates the year before the opening of the SIF compared to the year post-opening and found no significant increases in drug trafficking, assault, or robbery and a significant decrease in cases of vehicle break-ins and theft. SIFs are an example of a successful prevention effort at the tertiary level, in that they are aimed at decreasing the risk of infection and overdose associated with injection drug use. Since 2016, SIFs have been approved in Alberta, British Columbia, Ontario, and Quebec (Government of Canada, 2018).

Careers in Community Psychology: Activities, Job Titles & Training

A Model of CP Practice: Core Work Activities and Common CP Change Strategies

Recent years have seen a lively discussion about the particular expertise and professional identity of community psychologists. CP practice has been described in many ways, such as: (1) the goals that community psychologists seek to achieve; (2) the values, principles and frames of analysis that typify the field; (3) the settings where community psychologists can find work; (4) the skills, competencies and techniques typify CP practice; and (5) the personal characteristics, beliefs and attitudes that individuals bring to their practice (Arcidiacono, 2017; Julian, 2006; Kelly, 1971; Society for Community Research and Action [SCRA], 2012).

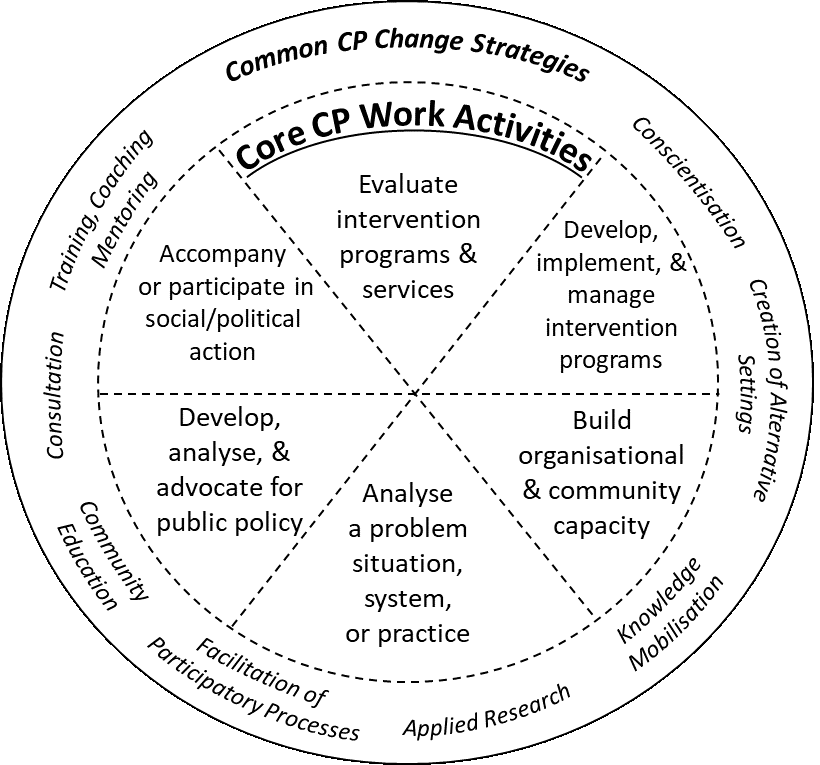

Following Ramos (2007) and Lavoie & Brunson (2010), and inspired by a framework developed by Foucher and Leduc (2008), this chapter presents a model of CP practice centered around six core work activities that community psychologists might participate in across diverse settings, as well as diverse change strategies that they might use as they conduct these activities (Figure 1). An activity-based approach seems consistent with CP’s emphasis on settings and roles (Hawe, 2017; Seidman, 1988) and complements other descriptions of practice in CP and other fields (Leach, 2008; Reeves, Fox, & Hodges, 2009). We stress that these activities are not exclusive to CP and that the contribution of other professions, as well as individuals and groups involved in change initiatives, should be recognized (Akhurst, Kagan, Lawthorn, & Richards, 2016; Dzidic et al., 2013; Lavoie & Brunson, 2010). However, community psychologists offer novel contributions to this work with their unique set of training and skills, frames of analysis, and focus on ecological and systems factors. We present this model of CP practice by first discussing the six proposed core CP work activities and provide a brief overview of several typical CP change strategies (Table 1).

Core CP Work Activities

Evaluate the Impact of Intervention Programs and Services.

A primary work activity for many community psychologists is to evaluate intervention programs, services, and systems change efforts. The goal of these activities is to collect information about the intervention’s intended and unintended effects; the processes by which those effects are achieved; and possible avenues for improving the intervention. Evaluation makes programs more accountable to stakeholders and funders and assists decision-makers as they consider whether to maintain, expand or eliminate a program (Cook, 2014; Wolfe, et al., 2017). It can also be considered a strategy for effecting social change and promoting social justice (Cook), with the goal of creating a more equitable, fair and just distribution of resources, opportunities, and privileges within society.

Evaluation objectives can be varied and are often broadly categorized in terms of outcome evaluations and process evaluations. The notion of outcome evaluation is probably most familiar. This involves documenting the impact of an intervention in relation to its stated objectives. Established, evidence-based programs may not always be successful in new contexts or populations, so outcome evaluations help to determine local impact. Process evaluation determines whether program components are actually being implemented as planned and if not, what barriers such as time or resource constraints might be getting in the way. Process evaluation can also address a program’s fit with its local context, for example examining whether the program is actually diverting resources from other important activities, whether it duplicates existing efforts, and whether it can be sustainable over time (Wolfe, et al., 2017).

Community psychologists can play an important role in evaluation by carrying out assessments in consultation with relevant stakeholders, providing training that enables actors to appropriate techniques and the evaluation culture, and by developing the tools that facilitate evaluation work. An integrated and sustained CP approach to program evaluation over time might include conceptualizing the program’s theory of change; planning activities and program components that have the best chance to produce desired changes; developing and executing a systematic plan to implement and support the program at multiple levels; ensuring the program fits local culture and context; evaluating whether the activities achieve their desired effects, and finding ways to ensure the sustainability of the program over time (Wolfe, et al., 2017). A CP approach to evaluation will also often include an analysis of benefits at a systems or community level, above and beyond the effects of individual change (Hawe, 1994).

Develop, Implement and Manage Intervention Programs.

Community psychologists are often called upon to develop, implement and manage intervention programs, especially those with prevention and health promotion goals (SCRA, 2012), and also programs for re-adaptation, crisis and trauma response, human resource capacity building, and the implementation of coordinated systems of care (Cook & Kilmer, 2012; Lavoie & Brunson, 2010; van de Hoef, Sundar, Austin, & Dostaler, 2011).

To find an appropriate intervention program, it is sometimes more efficient to identify an existing program and assess potential fit with the particular setting’s goals and resources. In other cases, it is more appropriate to develop a program suited to the particular needs and goals of the setting and compatible with existing resources, structures and practice. For both existing and locally-developed programs, ensuring the continued success of a program over time involves supervisory, management, and human resources activities, as well as financial management, marketing and strategic planning (McMahon & Wolfe, 2017; SCRA, 2012). Implementing programs in a sustainable way in any local context involves issues of fidelity to core program elements and fit and adaptation to the local context (Castro, Barrera, & Martinez, 2004). It is vital to ensure a supportive organisational and community context and organisational support for the program at multiple levels (Blanchet-Cohen & Brunson, 2010) and creating the conditions and processes that ensure that effective programs continue to operate successfully and even expand their reach (Cook, 2014).

Community psychologists can organize a collaborative approach among multiple community actors to identify stakeholder goals and assemble a meaningful and coherent package of intervention activities. The dual role of community psychologists both as researchers and as stakeholders make it possible to consider multiple perspectives and values, identify models, distill the evidence base, and systematize the choice of objectives and activities. Their training in developmental psychology also prepares them to consider issues related to age (Lavoie & Brunson, 2010).

Build Capacity at Organizational and Community Levels.

CP practitioners frequently participate in organisational and community capacity building activities aimed at developing links among citizens and organisations, strengthening networks and communication, and aligning efforts and resources to accomplish common goals (Wolff, 2010; Wolff et al., 2017). Some essential components of this capacity-building process include the ability to identify and convene diverse stakeholders; facilitate mutual trust; promote collaborative decision-making with authentic buy-in from all stakeholders; and to work together to act in ways that surpass what an individual actor would be able to do alone (Aspen Institute, 1996; Wolff).

At the organisational level, capacity building enhances the capacity of an organization to attain its goals by introducing or improving organizational tools, policies, and processes (SCRA, 2012). This work may involve helping an organisation to develop an organizational vision, mission, and strategic plan; aligning stakeholders, resources, and organizational processes around these priorities; building a communications strategy; promoting organisational learning; or putting mechanisms in place to monitor efforts and results (Hawe et al., 2000; Norton, McCleroy, Burdine, Felix, & Dorsey, 2002).

At the community level, capacity building fosters collaborative relationships and concrete action among community members, groups, and organizations (SCRA, 2012). It may involve helping community actors to define a shared vision and engaging, energizing and mobilizing individuals and groups around an issue of shared importance (SCRA). Grassroots community organizing involves working collaboratively with community members to gain the power to improve the conditions affecting their community (SCRA; Speer & Hughey, 1995). Community coalition building creates networks of organizational and resident stakeholders who work together across organizational boundaries to address a common issue (Allen, 2005; Foster-Fishman, Berkowitz, Lounsbury, Jacobson, & Allen, 2001; Francescato & Zani, 2017; Wolff et al., 2017).

Many other professions and disciplines recognize the importance of secure networks, social capital and collaborative relationships. Community psychologists participate in and foster these efforts, bringing among other things an awareness of social justice and equity and the importance of involving people who are directly affected by the conditions being addressed as well as those with relatively less power and voice (Rappaport, 1981; Wolff et al., 2017). Community psychologists are particularly attuned to identifying and mobilising existing strengths that exist, but which may be under-recognized or underutilised in the community (Kelly, 1971). They are also knowledgeable about relevant research and practice that may be taking place elsewhere and can suggest ideas that have been successful elsewhere (Dagenais, 2006; Lavoie & Brunson, 2010). A particular contribution of CP is the ability to use participation processes , such as participatory action research, participatory arts and theater, community forums, Delphi techniques, and small and large group facilitation techniques, to promote co-construction of knowledge and a positive climate for change efforts.

Analyse a Problematic Situation, System, or Practice.

The work of community psychologists sometimes involves making sense of an ambiguous and problematic situation in order to identify the problem better, create a shared and coherent understanding of the situation, and explore possible solutions. As Caplan & Nelson (1973) pointed out many years ago, what is done about a problem depends on how it is defined. If failure to obtain mental health care, for example, is defined in terms of individual characteristics and problems, such as lack of information or insufficient motivation, then person change intervention options are most logical and change efforts would likely focus on public awareness campaigns to diffuse information or increasing individuals’ awareness of the importance of care. If explanations are situation focused, for example, if lack of access was attributed to a lack of providers, high treatment costs, duplication of effort, and competition for resources and recognition, then system change in the form of mobile clinics working with community organisations to offer low-cost care or coordinated efforts to create interorganizational links would be a more logical solution (e.g., Lundburg, Ignatio, & Ramos, 2011; Wolff, 2014).

The analysis of a problem, a situation, a milieu, or practices consists of taking a critical, analytical and contextualized look at a social issue or a social object such as a community program, organization or institution. It may involve naming and documenting a little-known problem and raising awareness about its existence. It might involve documenting and exploring different viewpoints held by various stakeholders involved in the situation (Juras, Mackin, Curtis, & Foster-Fishman, 1997). It could involve taking on the role of “critical friend,” whereas a participant in the setting, the community psychologist tactfully confronts ways of thinking or acting that serve to maintain the status quo (Evans, Brown, de Schutter, & McGee, 2008). It helps to reveal how a group conceives a particular situation and suggests levers for change that might be created by introducing new mental models of the situation (Christens, Hanlin, & Speer, 2007).

Develop, Analyse and Advocate for Public Policy.

Community psychologists can be involved in efforts to influence public policy (Maton, 2016; Phillips, 2000). This type of work seeks to create change at the societal level by targeting the policies that govern its institutions and how they operate, the distribution of resources, and the structure of existing programs and services.

Community psychologists can play several public policy roles. They may provide research-based information on social problems and their possible solutions or work to raise awareness of an issue so that it becomes part of the political agenda. They can conduct policy analysis, examining the various policy options that are available and determining their actual or potential impact concerning a set of policy goals. They might participate in policy advocacy to influence decision-making processes and advocate for specific policies (Bouchard, 2001, 2010; McMahon & Wolfe, 2017; van de Hoef et al., 2011). Community psychologists can collaborate within a community to encourage citizen participation in policy-making or strengthen the capacity of institutional leaders to reach out to and listen to their constituents (Brunson & Boileau, 2008; Chavis, 1993). Community psychologists might work directly in the political system as a political attaché or policy staff (Phillips, 2000; van de Hoef et al., 2011), or even hold a position as an elected official or as a ministry-level decision-maker (Bouchard, 2001, 2011; Starnes, 2004).

Becoming involved in politics and the political process is not always easy or comfortable for psychologists, in part because of the contested nature of the political process (Bernier & Clavier, 2011; Fafard, 2015; Phillips, 2000). The distinction between providing information as a researcher versus acting as a lobbyist or political activist can be challenging to manage (Bouchard, 2001; Francescato & Zani, 2017). Even when persuasive arguments are based on a solid research base, it can be difficult to accept that scientific knowledge is only one element among many in a political decision-making process (Bernier & Clavier; Bouchard; Fafard).

Although few CP training programs provide training on the process of public governance (Phillips, 2000), community psychologists bring to this field a broad knowledge of topics of interest to social policy planners (citizen participation, the influence of social networks, exclusion, etc.) and a broad ecological analysis of phenomena, including exo and macrosystem factors. They are skilled at building and sustaining working relationships and effective communication with a variety of stakeholders, and can apply these skills with policy makers, elected officials, governmental staff, and community leaders (SCRA, 2012).

Accompany and Participate in Social and Political Action.

CP typically works with disempowered groups in contexts that are constructed economically, politically and historically and proposes structural and contextualized understanding of these social situations. When these groups encounter social and economic interests that differ from their own, the work inevitably enters into the realm of politics and social action (Burton, Kagan & Duckett, 2012). Social action, defined as efforts to address inequities of power and privilege between an oppressed group and society at large, is an option for challenging these existing power relations in society (Le Bossé & Dufort, 2001; Lykes et al., 2003; Moane, 2003; Rothman & Tropman, 1987).

Community psychologists may engage in explicitly political commitment as experts with particular knowledge of the evidence base and the risks and harms involved in a particular situation. They might work with community groups to organize a protest movement, participate in a collective advocacy process, or conduct a grassroots community organizing with a rights-based focus. They can help to maintain positive group dynamics, a valuable contribution for small groups engaged in difficult campaigns (Burton, et al., 2012).

Taking a stand on social issues requires engaging in value debates and taking on political issues. As with policy analysis and advocacy, there can be tensions between acting as a practitioner/professional versus as a political activist (Lavoie & Brunson, 2010; Francescato & Zani, 2017). Some resolution of this dilemma can be found when community psychologists are also able to identify with a social movement as part of their civic and personal identity and to recognize their own and others’ rights to act as fully enfranchised members of civil society (Burton, et al., 2012; Dzidic et al., 2013).

Common CP Change Strategies

Community psychologists use diverse strategies to promote change across different activities and settings. Table 2 briefly highlights a number of change strategies typical to CP practice that have been discussed in detail elsewhere (Bond et al., 2017b; Francescato & Zani, 2017; Lavoie & Brunson, 2010). Other strategies can certainly be added depending on the area of specialization.

| Strategy Type | Description |

| Conscientisation | Creates a group process in which social relations and collective action lead to greater awareness of the social and political structures that limit and distribute power in society, and the possibility for change (Franscescato & Zani, 2017; Montero 2012; Montero et al., 2017). |

| Alternative settings | Seeks to move completely out of the current system and create a new resource, challenging the established order instead of trying to change an existing service. Some examples include mutual aid groups, cooperatives, social economy enterprises, counterspaces (Case & Hunter, 2012; Cherniss & Deegan, 2000; Francescato & Zani 2017). |

| Knowledge mobilisation | Aims to reduce the gap between science and practice by involving practitioners and clients in creating knowledge and applying it in a particular context (Dagenais, 2006; Worton et al., 2017). |

| Applied research | Allows stakeholders to identify solutions to problems by gathering information, developing and testing hypotheses, crafting change processes adapted to a particular context, and evaluating their impact in that specific context (Juras et al., 1997; van de Hoef et al., 2011). |

| Participation | Seeks to understand and improve fair and diverse participation in work and life settings. Participatory action research promotes social change and quality of life for oppressed and exploited communities (Creswell, Hanson, Clark Plano, & Morales, 2007; SCRA, 2012). |

| Community education | Aims to educate members of the community and promote healthy behaviour change related to using social marketing and public awareness campaigns (SCRA, 2012; Gagné, Lachance, Thomas, Brunson, & Clément, 2014). |

| Consultation | Builds a collaborative process aimed at identifying and solving problems and identifying useful data and resources, takes place within the context of a specific mandate given by a group, organisation or community. In CP, consultation is envisaged as a tool for development and empowerment that often takes place in complex systems involving many stakeholders (Laprise & Payette, 2001, Meyers, 2002). |

| Training, coaching, mentoring | Develops individual and groups’ abilities to work more effectively towards their goals and is especially effective when individual capacity building is supported by tools and processes that provide continuing support. Training in such skills as reflective practice or evaluation can be a crucial component in capacity building efforts (Lavoie & Brunson, 2010; SCRA, 2012). |

Job Settings and Titles

As McMahon and colleagues (2015) have aptly pointed out, few job ads announce that they are looking for a community psychologist to fill the position! However, the training and experience that community psychologists acquire through academic programs and work experience typically equip them well to be employed in a wide variety of settings. Given its interdisciplinary focus and collaborative traditions, CP graduates often contribute their skills, knowledge and expertise to a specific problem area. This in fact creates a dilemma for the field: While other disciplines such as public health and social work have reserved job titles and a clear job market, Canadian CP does not currently have this level of infrastructure in place. Thus, unlike other fields that draw people into institutional structures that reinforce their professional identity, the “peculiar success” of CP has created centripetal forces which tend to limit graduates’ opportunities to identify with the field on an everyday level in their professional work (Neigher et al., 2011; Snowden, 1987). In this way, CP may be a victim of its success in promoting collaborative, interdisciplinary and power-sharing approaches to solving social problems and preparing its graduates for a wide variety of careers. It can therefore be difficult to highlight the variety of contributions of community psychologists.

Despite this dilemma, graduates of CP programs can be found working in many types of settings, including academic settings, philanthropic organisations and private foundations, health and human service agencies, municipal, regional, provincial and federal governments; medical centers, public health settings, comprehensive community initiatives, self-help groups, prevention organizations, community mental health centers, nonprofits, schools, community-based organizations, advocacy groups, religious institutions, and neighborhood groups. They work in organisations offering applied research, consultation and evaluation services, and community development, architectural, planning, and environmental firms. They may also be found in corporations or as researchers in community organizations, universities, think tanks, or government agencies (McMahon & Wolfe, 2017; Neigher et al., 2011; Wolff, 2014).

Community psychologists are well prepared to promote mental health and community well-being in a variety of roles. Some relevant job titles might include (Hakim, 2010; McMahon & Wolfe, 2017; Viola et al., 2017):

- community mental health worker

- grassroots organizer

- community development specialist or urban planner

- program or project director

- grant writer

- trainer

- director of a nonprofit or community-based organization

- research/evaluation consultant

- coordinator for a community coalition

- policy analyst

- governmental administrative staff or political attaché

- executive staff of a nonprofit or for-profit organization.

Interestingly, Franscescato and Zani (2017) describe how community psychologists in Italy were successful in advocating for and implementing positions of territorial community psychologists, who are mandated to conduct regional analyses to assess strengths and problems and analyse and coordinate the local network of institutions, associations and groups. For compelling descriptions of diverse career paths of individual community psychologists, see Bouchard, 2010; Chavis, 1993; van de Hoef et al., 2011; Wolff, 2014).

Training in Community Psychology

At the undergraduate level, though there is no formal training in CP within Canada, there are numerous undergraduate courses on the topic offered at institutions across the country (see Table 2). Training in CP at the undergraduate and graduate levels is often pursued through supervision by professors with CP expertise who identify as community psychologists without necessarily being affiliated with a formal CP program. Indeed, formal graduate programs in CP are currently only available in three Canadian universities. Two stand-alone CP graduate programs are offered at Wilfrid Laurier University and at the Université du Québec à Montréal, and a clinical psychology program with a specialisation in CP is offered at the University of Ottawa. Specific postdoctoral training in CP is not yet offered within Canada, though many fellowships are available within the United States, including at Penn State University, Stanford Medical Center and Veterans Affairs, and the Center for AIDS Intervention Research in Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

Those who have been in the position of interviewing and accepting students into CP graduate programs have provided insights into the application process. Importantly, as CP is an action-oriented field, CP supervisors look for practical field experience in addition to research experience. Another essential component for applicants includes an understanding of CP and what makes each student passionate about it. For example, a student may see the value of a CP program in applying multiple levels of analysis to their topic of interest. A simple and accessible way to learn more about CP is to explore the free online resource The Community Toolbox (Center for Community Health and Development, 2019).

In considering graduate school in CP, it is also useful to note that a PhD in CP is not required to be active in the field. Community psychologists fill many different roles, and CP-specific training is not required for many of these positions. Individuals working in CP related positions hold varying degree levels, including undergraduate and master’s as well as doctoral degrees.

| Level | Degree Type | Institution |

| Undergraduate | ||

| – | Wilfrid Laurier University | |

| – | University of Windsor | |

| – | Cape Breton University | |

| – | McGill University | |

| – | University of New Brunswick | |

| – | Thompson Rivers University | |

| – | UQAM | |

| – | Saint Mary’s University | |

| Master’s | ||

| Master of Arts in Community Psychology | Wilfrid Laurier University | |

| Master of Public Policy and Administration in Social Change | Adler University | |

| Doctoral | ||

| PhD in Community Psychology | Wilfrid Laurier University | |

| UQAM | ||

| PhD in Experimental Psychology – Social/Community | University of Ottawa | |

| Other | ||

| Undergraduate Practicum | Carleton University |

Conclusion

Community psychologists share many of the values, concepts and change strategies of other community-focused specialties, such as applied sociology, social work, community economic development, public health, applied anthropology, and prevention science. However, CP adds a particular constellation of perspectives on community change and intervention compared to other disciplines. CP practice is, among other things, fundamentally rooted in an empirical approach, using research not only to describe social problems but as a lever for change. CP is rooted in psychology and uses psychological and psychosocial knowledge to promote social change. Community psychologists often adopt a critical and analytical approach to environments and systems through the use of concepts such as social regularities, person-environment fit, and ecological analysis. They hold a tolerance for ambiguity and the ability to legitimize multiple points of view. They seek out individual and group strengths and strive to identify levers for change that are already present in the situation. Community psychologists move beyond analysis towards action, by establishing a climate of mobilization and synergy and by promoting concrete possibilities for change (Laprise & Payette, 2001). These features of CP contribute to the wide variety of applications and careers that community psychologists can pursue.

References

Akhurst, J., Kagan, C., Lawthorn, R., & Richards, M. (2016). Community psychology practice competencies: perspectives from the UK. Global Journal of Community Psychology Practice, 7(4), 1-16.

Allen, N. E. (2005). A multi‐level analysis of community coordinating councils. American Journal of Community Psychology, 35(1-2), 49-63. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-005-1889-5

Arcidiacono, C. (2017). The community psychologist as a reflective plumber. Global Journal of Community Psychology Practice, 8(1), 1–16.

Aspen Institute (1996). Measuring community capacity building: A workbook in progress for rural communities. Washington, DC: Author.

Aubry, T., Goering, P., Veldhuizen, S., Adair, C. E., Bourque, J., Distasio, J., … Tsemberis, S. (2016). A multiple-city RCT of housing first with assertive community treatment for homeless Canadians with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services, 67(3), 275-281. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201400587

Aubry, T., Sylvestre, J., & Ecker, J. (2010). Community psychology training in Canada in the new millennium. Canadian Psychology, 51(2), 89-95. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0018134

Babarik, P. (1979). The buried Canadian roots of community psychology. Journal of Community Psychology, 7, 362–367. https://doi.org/10.1002/1520-6629(197910)7:4<362::AID-JCOP2290070416>3.0.CO;2-X

Bernier, N. F., & Clavier, C. (2011). Public health policy research: making the case for a political science approach. Health promotion international, 26(1), 109-116. doi: 10.1093/heapro/daq079

Blanchet-Cohen, N., & Brunson, L. (2014). Creating settings for youth empowerment and leadership: An ecological perspective. Child & Youth Services, 35(3), 216-236. https://doi.org/10.1080/0145935X.2014.938735

Bond,. I. E. Serrano-García, C. B. Keys, C. & Shinn, M. (2017a). APA handbook of community psychology: Vol. 1. Theoretical foundations, core concepts, and emerging challenges. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Bond,. I. E. Serrano-García, C. B. Keys, C. & Shinn, M. (2017b). APA Handbook of Community psychology: Vol. 2. Methods for community research and action for diverse groups and issues . Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Bouchard, C. (2001). Inspirer, soutenir et rénover les politiques sociales. In F. Dufort & J. Guay (Eds.), Agir au cœur des communautés. La psychologie communautaire et le changement social (pp. 343-368). Saint-Nicolas, QC: Les Presses de l’Université Laval.

Bouchard, C. (2010). Construire un monde plus viable : plaidoyer pour une psychologie de l’engagement civique. Congrès de l’Ordre des psychologues du Québec, Québec, Québec : October 30, 2010.

Bouchard, C. (2011). 1. De Skinner à Bronfenbrenner ou de l’utopie à l’engagement: parcours d’un psychologue communautaire. In T. Saias (Ed.), Introduction à la psychologie communautaire (pp. 1-11). Paris, FR: Dunod.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Brunson, L. & Boileau, G. (2008). La voix des parents : Préparation d’un portrait de la communauté par, pour et avec les parents — Guide du processus. Guide d’animation présenté à Québec Enfants, Montréal, Québec (86 pp.).

Burns, J. C., Cooke, D. Y., & Schweidler, C. (2011). A short guide to community based participatory action research. Los Angeles, CA: Advancement Project. Retrieved from https://hc-v6-static.s3.amazonaws.com/media/resources/tmp/cbpar.pdf

Burton, M., Kagan, C., & Duckett, P. (2012). Making the psychological political–challenges for community psychology. Global Journal of Community Psychology Practice, 3(4), 1-11.

Campbell, R. (2010). Commentary: What’s the ‘right’ method in community research. In G. Nelson & I. Prilleltensky (Eds.), Community psychology: In pursuit of liberation and well-being (2nd ed., pp. 308-310). London, UK: MacMillan.

Caplan, G. (1961). Prevention of mental disorders in children: Initial explorations. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Caplan, N., & Nelson, S. D. (1973). On being useful: The nature and consequences of psychological research on social problems. American Psychologist, 28(3), 199. doi: 10.1037/h0034433

Case, A. D., & Hunter, C. D. (2012). Counterspaces: A unit of analysis for understanding the role of settings in marginalized individuals’ adaptive responses to oppression. American Journal of Community Psychology, 50(1-2), 257-270.

Castro, F. G., Barrera, M., & Martinez, C. R. (2004). The cultural adaptation of prevention interventions: Resolving tensions between fidelity and fit. Prevention Science, 5(1), 41-45. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:PREV.0000013980.12412.cd

Center for Community Health and Development (2019). The community toolbox [resource]. Retrieved from https://ctb.ku.edu/en

Chavis, D. M. (1993). A future for community psychology practice. American Journal of Community Psychology, 21(2), 171–183. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00941620

Cherniss, C., & Deegan, G. (2000). The creation of alternative settings. In J. Rappaport & E. Seidman (Eds.), Handbook of Community Psychology (pp. 359 –378). New York, NY: Plenum Press.

Christens, B. D., Hanlin, C. E., & Speer, P. W. (2007). Getting the social organism thinking: Strategy for systems change. American Journal of Community Psychology, 39(3-4), 229-238. doi: 10.1007/s10464-007-9119-y

Cook, J. R. (2014). Using evaluation to effect social change. American Journal of Evaluation, 36(1), 107–117. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098214014558504

Cook, J. R., & Kilmer, R. P. (2012). Systems of care: New partnerships for community psychology. American Journal of Community Psychology, 49(3-4), 393-403. doi: 10.1007/s10464-012-9516-8.

Creswell, J. W., Hanson, W. E., Clark Plano, V. L., & Morales, A. (2007). Qualitative research designs: Selection and implementation. The Counseling Psychologist, 35(2), 236-264.

Dagenais, C. (2006). Vers une utilisation accrue des résultats de la recherche par les intervenants sociaux. Quels modèles de transfert de connaissance privilégier? Les Sciences de l’Éducation pour l’Ère nouvelle, 3, 23-35. doi: 10.3917/lsdle.393.0023

Dalton, J. H., Elias, M. J., & Wandersman, A. (2007). Community psychology: Linking individuals and communities (2nd ed.). Belmont, CA: Thomson Wadsworth.

Dzidic, P., Breen, L. J. & Bishop, B. J. (2013). Are our competencies revealing our weaknesses? A critique of community psychology practice competencies. Global Journal of Community Psychology Practice, 4(4), 1–10.

Evans, S. D., Brown, N., deSchutter, J., & McGee, S. (2008, mai). The role of the « critical friend » in the community-university partnership. Communication présentée au 4ième Colloque de psychologie communautaire Québec-Ontario, Montréal, Québec.

Evans, S. D. Duckett, P., Lawthorn, R., & Kivell, N. (2017). Positioning the critical in community psychology. In M. A. Bond,. I. E. Serrano-García, C. B. Keys, & M. Shinn (2017). APA Handbook of Community Psychology: Vol. 1. Theoretical Foundations, Core Concepts, and Emerging Challenges. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Fafard, P. (2015). Beyond the usual suspects: Using political science to enhance public health policy making. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 69(11), 1129-1132. http://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2014-204608

Fortin-Pellerin, L., Pouliot-Lapointe, J., Thibodeau, C., & Gagne, M-H. (2007). The Canadian journal of community mental health from 1982 to 2006: A content analysis. Canadian Journal of Community Mental Health, 26(1), 23-45. https://doi.org/10.7870/cjcmh-2007-0005

Foster-Fishman, P. G., Berkowitz, S. L., Lounsbury, D. W., Jacobson, S., & Allen, N. A. (2001). Building collaborative capacity in community coalitions: A review and integrative framework. American Journal of Community Psychology, 29(2), 241-261. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010378613583

Foucher, R., & Leduc, F. (2008). Domaines de pratique et compétences professionnelles des psychologues du travail et des organisations (2e éd.). Montréal, QC: Éditions Nouvelles.

Francescato, D., & Zani, B. (2013). Community psychology practice competencies in undergraduate and graduate programs in Italy. Global Journal of Community Psychology Practice, 4(4), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.7728/0404201303

Francescato, D., & Zani, B. (2017). Strengthening community psychology in Europe through increasing professional competencies for the new Territorial Community Psychologists. Global Journal of Community Psychology Practice, 8(1), 1–14.

Gagné, M. H., Lachance, V., Thomas, F., Brunson, L., & Clément, M. È. (2014). Prévenir la maltraitance envers les enfants au moyen du marketing social. Canadian Journal of Community Mental Health, 33(2), 85-107.

Gottlieb, B. H., & Russell, C. C. (1989). Better beginnings, better futures: Primary prevention in Ontario. Canadian Journal of Mental Health, 8(2), 151-152.

Government of Canada (2018). Supervised consumption sites: status of applications. Retrieved from https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/substance-abuse/supervised-consumption-sites/status-application.html#app

Hasford, J., Loomis, C., Nelson, G., & Pancer, S. M. (2013). Youth narratives on community involvement and sense of community and their relation to participation in an early childhood development program. Youth & Society. Advance online publication. http://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X13506447

Hawe, P. (1994). Capturing the meaning of “community” in community intervention evaluation: Some contributions from community psychology. Health Promotion International, 9, 199 –210.

Hawe, P. (2017). The contribution of social ecological thinking to community psychology: Origins, practice, and research. In M. A. Bond,. I. E. Serrano-García, C. B. Keys, & M. Shinn (2017). APA Handbook of Community Psychology: Vol. 1. Theoretical Foundations, Core Concepts, and Emerging Challenges. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Hawe, P., King, L., Noort, M., Jordens, C., Gifford, S., & Lloyd, B. (2000). Indicators to help with capacity building in health promotion. Sidney, AU: Australian Centre for Health Promotion, Health Promotion International, NSW Health Department.

Hayward, K., Loomis, C., Nelson, G., Pancer, M., & Peters, R. DeV. (2011). A toolkit for building better beginnings and better futures. Kingston, ON: Better Beginnings, Better Futures Research Coordination Unit.

Jason, L. A. & O’Brien, J. (2018). What is unique to our field? The Community Psychologist, 51(3).

Jason, L. A., Stevens, E., Ram, D. Miller, S. A., Beasley, C. R., & Gleason, K., (2016). Theories in the field of community psychology. Global Journal of Community Psychology Practice, 7(2), 1-27.

Julian, D. (2006). Defining community psychology practice: Meeting the needs and realizing the dreams of the community. The Community Psychologist, 39(4), 66-69.

Juras, J. L., Mackin, J. R., Curtis, S. E., & Foster-Fishman, P. G. (1997). Key concepts of community psychology: Implications for consulting in educational and human service settings. Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation, 8, 111-133. https://doi.org/10.1207/s1532768xjepc0802_2

Kelly, J. G. (1971). Qualities for the community psychologist. American Psychologist, 26(10), 897-903. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/h0032231

Kelly, J. G. (1986). Context and process: An ecological view of the interdependence of practice and research. American Journal of Community Psychology, 14(6), 581-589. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00931335

Kerr, T., MacPherson, D., & Wood, E. (2008). Establishing North America’s first safer injection facility: lessons from the Vancouver experience. In A. Stevens (Ed.). Crossing frontiers: International developments in the treatment of drug dependence. Brighton, UK: Pavilion Publishing.

Kloos, B., & Shah, S. (2009). A social ecological approach to investigating relationships between housing and adaptive functioning for persons with serious mental illness. American Journal of Community Psychology, 44, 316-326. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-009-9277-1

Laprise, R., & Payette, M. (2001). Le choix d’un modèle de consultation selon une perspective communautaire. In F. Dufort & J. Guay (Eds.), Agir au cœur des communautés. La psychologie communautaire et le changement social (pp. 187-214). Saint-Nicolas, QC: Les Presses de l’Université Laval.

Lavoie, F., & Brunson, L. (2010). La pratique de la psychologie communautaire. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie Canadienne, 51(2), 96–105. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018085

Lavoie, F., Borkman, T., & Gidron, B. (Eds.). (1994). Self-help and mutual aid groups: International and multicultural perspectives. New York, NY: Haworth Press.

Le Bossé, Y., & Dufort F. (2001). Le pouvoir d’agir (empowerment) des personnes & des communautés : Une autre façon d’intervenir. In F. Dufort & J. Guay (Eds.), Agir au coeur des communautés : La psychologie communautaire et le changement social (pp. 75-116). Sainte-Foy, QC: Presses de l’Université Laval.

Leach, D. C. (2008). Competencies: from deconstruction to reconstruction and back again, lessons learned. American Journal of Public Health, 98(9), 1562–1564. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2007.125302

Lundburg, K., Ignacio, C. R., & Ramos, C. M. (2011). The mobile care health project: Providing dental care in rural Hawai’i communities. Global Journal of Community Psychology Practice, 1(3), 32-36.

Lykes, M. B., TerreBlanche, M., & Hamber, B. (2003). Narrating survival and change in Guatemala and South Africa: The politics of representation and a liberatory community psychology. American Journal of Community Psychology, 31(1/2), 79-90.

Martín-Baró, I. (1994). Writings for a Liberation Psychology. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Maton, K. I. (2016). Influencing social policy: Applied psychology serving the public interest. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

McMahon, S. D., & Wolfe, S. M. (2017). Career opportunities for community psychologists. APA handbook of community psychology, 2 Methods for community research and action for diverse groups and issues, 645–659.

McMahon, S. D., Jimenez, T. R., Bond, M. A., Wolfe, S. M., & Ratcliffe, A. W. (2015). Community psychology education and practice careers in the 21st century. In V. C. Scott & S. M. Wolfe (Eds.), Community psychology: Foundations for practice (pp. 379–409). London, UK: SAGE Publications, Ltd.

Meyers, A. B. (2002). Developing nonthreatening expertise: Thoughts on consultation training from the perspective of a new faculty member. Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation, 13, 55– 67.

Moane, G. (2003). Bridging the personal and the political : Practices for a liberation psychology. American Journal of Community Psychology, 31(1-2), 91-101.

Montero, M. (2012). From complexity and social justice to consciousness: Ideas that have build a community psychology. Global Journal of Community Psychology Practice, 3(1), 1–13.

Montero, M., Sonn, C., & Burton, M. (2017). Community psychology and liberation psychology : A creative synergy for an ethical and transformative praxis. In M. A. Bond,. I. E. Serrano-García, C. B. Keys, & M. Shinn (Eds.), APA Handbook of Community Psychology: Vol. 1. Theoretical Foundations, Core Concepts, and Emerging Challenges (pp. 149-167). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Neal, J. W. (2016). Phenomenon of interest, framework, or theory? Building better explanations in Community Psychology. Global Journal of Community Psychology Practice, 7(2), 1-6.

Neigher, W. D., Ratcliffe, A. W., Wolff, T., Elias, M., & Hakim, S. M. (2011). A value proposition for community psychology. Global Journal of Community Psychology Practice, 2(3), 1–21.

Nelson, G. (2006). Mental health policy in Canada. In A. Westhues (Ed.), Canadian social policy: Issues and perspectives (4th ed., pp. 245- 266). Waterloo, ON: Wilfrid Laurier University Press.

Nelson, G., & Aubry, T. (2010). Introduction to community psychology in Canada: past, present, and future. Canadian Psychology 51(2), 77-78. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0019740

Nelson, G., Kloos, B., & Ornelas, J. (2014). Transformative change in community mental health. In G. Nelson, B. Kloos, & J. Ornelas (Eds.), Community psychology and community mental health: Towards transformative change. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press

Nelson, G., Lavoie, F., & Mitchell, T. (2007). The history and theories of community psychology in Canada. In S. M. Reich, M. Riemer, I. Prilleltensky, & M. Montero (Eds.), International Community Psychology (pp. 13–36). New York, NY: Springer US

Nelson, G., Lord, J., & Ochoka, J. (2001). Shifting the paradigm in community mental health: towards empowerment and community. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.3138/9781442679900

Nelson, G., Ochocka, J., Janzen, R., Trainor, J., Goering, P., & Lomotey, J. (2007). A longitudinal study of mental health consumer/survivor initiatives: Part V—Outcomes at three-year follow-up. Journal of Community Psychology, 35, 655–665. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.20171

Nelson, G., Stefancic, A., Rae, J., Townley, G., Tsembers, S., Macnaughton, E., … Georging, P. (2014). Early implementation evaluation of a multi-site housing first intervention for homeless people with mental illness: a mixed methods approach. Evaluation and Program Planning, 43, 16-26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2013.10.004

Norton, B., McLeroy, K., Burdine, J., Felix, R., & Dorsey, A. (2002). Community capacity: Concept, theory, and methods. In D. R. DiClemente, R. Crosby, & M. Kegler (Eds.), Emerging theories in health promotion practice and research (pp. 194-227). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Pancer, S. M., Nelson, G., Hasford, J., & Loomis, C. (2012). The Better Beginnings, Better Futures project: Long-term parent, family, and community outcomes of a universal, comprehensive, community-based prevention approach for primary school children and their families. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 23, 187-205. https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.2110

Peters, R. DeV., Nelson, G., Petrunka, K., Pancer, S. M., Loomis, C., Hasford, J., … Van Andel, A. (2010). Investing in our future: Highlights of Better Beginnings research findings at grade 12. Kingston, ON: Better Beginnings Research Coordination Unit, Queen’s University.

Peters, R. DeV., Petrunka, K., Kahn, S., Howell-Moneta, A., Nelson, G., Pancer, S. M., & Loomis, C. (2016). Cost-savings analysis of the Better Beginnings, Better Futures community-based project for young children and their families: A 10-Year Follow-up. Prevention Science, 17(2), 237–247. doi: 10.1007/s11121-015-0595-2

Phillips. D. A. (2000). Social policy and community psychology. In J. Rappaport & E. Seidman (Eds.), Handbook of community psychology (pp. 397-419). New York, NY: Plenum.

Pols, H. (2000). Between the laboratory, the school, and the community: The psychology of human development, Toronto, 1916-1956. Canadian Journal of Community Mental Health, 19(2), 13-30. https://doi.org/10.7870/cjcmh-2000-0013

Prilleltensky, I. (1997). Values, assumptions, and practices: Assessing the moral implications of psychological discourse and action. American Psychologist, 52(5), 517-535.

Ramos, C. M. (2007). A conceptual framework for community psychology practice. The Community Psychologist, 40(4), 53–54.

Rappaport, J. (1981). In praise of paradox: A social policy of empowerment over prevention. American Journal of Community Psychology, 9(1), 1-25.

Reeves, S., Fox, A., & Hodges, B. D. (2009). The competency movement in the health professions: Ensuring consistent standards or reproducing conventional domains of practice? Advances in Health Sciences Education : Theory and Practice, 14(4), 451–453. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-009-9166-2

Reich, S. M., Riemer, M., Prilleltensky, I., & Montero, M. (2007). International Community Psychology. New York, NY: Springer US

Rothman, J., & Tropman E. (1987). Models of community organizations and macro practice perspectives: Their mixing and phasing. In F. Cox, J. Erlich, J. Rothman, & J. Tropman, (Eds), Strategies of community organization: Macro practice (4th ed.) (pp. 3-26). Itasca, Illinois: F.E. Peacock Publishers, Inc.

Seidman, E. (1988). Back to the future, community psychology: Unfolding a theory of social intervention. American Journal of Community Psychology, 16(1), 3-24.

Snowden, L. R. (1987). The peculiar successes of community psychology: Service delivery to ethnic minorities and the poor. American Journal of Community Psychology, 15(5), 575-586.

Society for Community Research and Action (2012). Competencies for community psychology practice: Draft August 15, 2012. The Community Psychologist, 45(4), 7–14.

Somers, J. M., Rezansoff, S. N., Moniruzzaman, A., Palepu, A., & Patterson, M. (2013). Housing first reduces re-offending among formerly homeless adults with mental disorders: Results of a randomized controlled trial. PLOS ONE, 8(9), 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0072946

Speer, P. W., & Hughey, J. (1995). Community organizing: An ecological route to empowerment and power. American Journal of Community Psychology, 23(5), 729-748.

Starnes, D. M. (2004). Community psychologists — get in the arena! American Journal of Community Psychology, 33(1-2), 3-6.

Stein, C. H. (2007). Commentary – Competencies and toolboxes or lessons learned along the journey? The nature of graduate education in community psychology. The Community Psychologist, 40(2), 101-102.

Tsemberis, S. (1999). From streets to homes: An innovative approach to supported housing for homeless adults with psychiatric disabilities. Journal of Community Psychology, 27, 225-241. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1520-6629(199903)27:2<225::AID-JCOP9>3.0.CO;2-Y

Tsemberis, S., Gulcur, L., & Nakae, M. (2004). Housing first, consumer choice, and harm reduction for homeless individuals with a dual diagnosis. American Journal of Public Health, 94(4), 651–656. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.94.4.651

van de Hoef, S., Sundar, P., Austin, S., & Dostaler, T. (2011). And then what? Four community psychologists reflect on their careers ten years after graduation. Global Journal of Community Psychology Practice, 2(2), 1–8.

Viola, J. J., Glantsman, O., Williams, A., & Stevension, C. (2017). Answers to all your questions about careers in community psychology. In J. J. Viola & O. Glantsman (Eds.), Diverse Careers in Community Psychology. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780190457938.001.0001

Walsh-Bowers, R. (1998). Community psychology in the Canadian psychological family. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie Canadienne, 39(4), 280-287.

Wolfe, S. M., Scott, V. C., & Jimenez, T. R. (2013). Community psychology practice competencies: A global perspective. Global Journal of Community Psychology Practice, 4(4), 1–9.

Wolff, T. (2010). The power of collaborative solutions: Six principles and effective tools for building healthy communities. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Wolff, T. (2014). Community psychology practice: Expanding the impact of psychology’s work. The American Psychologist, 69(8), 803–813. doi: 10.1037/a0037426

Wolff, T., Minkler, M., Wolfe, S. W., Berkowitz, B., Bowen, L., Butterfoss, F. D., … Lee, K. S. (2017). Collaborating for equity and justice: Moving beyond collective impact. Nonprofit Quarterly, 9, 42-53.

Wood, E., Tyndall, M. W., Lai, C., Montanero, J. S., & Kerr, T. (2006). Impact of a medically supervised safer injecting facility on drug dealing and other drug-related crime. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy 1, 13. https://doi.org/10.1186/1747-597X-1-13

Worton, K., Loomis, C., Pancer, M., Nelson, G., & Peters. R. (2017). Evidence to impact: A community knowledge mobilization evaluation framework. Gateways International Journal, 10, 121–142. https://doi.org/10.5130/ijcre.v10i1.5202

Please reference this chapter as:

Brunson, L., Gilmer, A., & Loomis, C. (2019). Applications and careers in community psychology: Practicing in settings, systems, and communities to build well- being and promote social justice. In M. E. Norris (Ed.), The Canadian Handbook for Careers in Psychological Science. Kingston, ON: eCampus Ontario. Licensed under CC BY NC 4.0. Retrieved from https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/psychologycareers/chapter/applications-and-careers-in-community-psychology/

- We thank Tom Wolff, Elizabeth Thomas and Cynthia Moore for their comments on early drafts of this chapter. ↵