19 Understanding Psychological Measurement

Learning Objectives

- Define measurement and give several examples of measurement in psychology.

- Explain what a psychological construct is and give several examples.

- Distinguish conceptual from operational definitions, give examples of each, and create simple operational definitions.

- Distinguish the four levels of measurement, give examples of each, and explain why this distinction is important.

What Is Measurement?

Measurement is the assignment of scores to individuals so that the scores represent some characteristic of the individuals. This very general definition is consistent with the kinds of measurement that everyone is familiar with—for example, weighing oneself by stepping onto a bathroom scale, or checking the internal temperature of a roasting turkey using a meat thermometer. It is also consistent with measurement in the other sciences. In physics, for example, one might measure the potential energy of an object in Earth’s gravitational field by finding its mass and height (which of course requires measuring those variables) and then multiplying them together along with the gravitational acceleration of Earth (9.8 m/s2). The result of this procedure is a score that represents the object’s potential energy.

This general definition of measurement is consistent with measurement in psychology too. (Psychological measurement is often referred to as psychometrics.) Imagine, for example, that a cognitive psychologist wants to measure a person’s working memory capacity—their ability to hold in mind and think about several pieces of information all at the same time. To do this, she might use a backward digit span task, in which she reads a list of two digits to the person and asks them to repeat them in reverse order. She then repeats this several times, increasing the length of the list by one digit each time, until the person makes an error. The length of the longest list for which the person responds correctly is the score and represents their working memory capacity. Or imagine a clinical psychologist who is interested in how depressed a person is. He administers the Beck Depression Inventory, which is a 21-item self-report questionnaire in which the person rates the extent to which they have felt sad, lost energy, and experienced other symptoms of depression over the past 2 weeks. The sum of these 21 ratings is the score and represents the person’s current level of depression.

The important point here is that measurement does not require any particular instruments or procedures. What it does require is some systematic procedure for assigning scores to individuals or objects so that those scores represent the characteristic of interest.

Psychological Constructs

Many variables studied by psychologists are straightforward and simple to measure. These include age, height, weight, and birth order. You can ask people how old they are and be reasonably sure that they know and will tell you. Although people might not know or want to tell you how much they weigh, you can have them step onto a bathroom scale. Other variables studied by psychologists—perhaps the majority—are not so straightforward or simple to measure. We cannot accurately assess people’s level of intelligence by looking at them, and we certainly cannot put their self-esteem on a bathroom scale. These kinds of variables are called constructs (pronounced CON-structs) and include personality traits (e.g., extraversion), emotional states (e.g., fear), attitudes (e.g., toward taxes), and abilities (e.g., athleticism).

Psychological constructs cannot be observed directly. One reason is that they often represent tendencies to think, feel, or act in certain ways. For example, to say that a particular university student is highly extraverted does not necessarily mean that she is behaving in an extraverted way right now. In fact, she might be sitting quietly by herself, reading a book. Instead, it means that she has a general tendency to behave in extraverted ways (e.g., being outgoing, enjoying social interactions) across a variety of situations. Another reason psychological constructs cannot be observed directly is that they often involve internal processes. Fear, for example, involves the activation of certain central and peripheral nervous system structures, along with certain kinds of thoughts, feelings, and behaviors—none of which is necessarily obvious to an outside observer. Notice also that neither extraversion nor fear “reduces to” any particular thought, feeling, act, or physiological structure or process. Instead, each is a kind of summary of a complex set of behaviors and internal processes.

The Big Five

The Big Five is a set of five broad dimensions that capture much of the variation in human personality. Each of the Big Five can even be defined in terms of six more specific constructs called “facets” (Costa & McCrae, 1992)[1].

The conceptual definition of a psychological construct describes the behaviors and internal processes that make up that construct, along with how it relates to other variables. For example, a conceptual definition of neuroticism (another one of the Big Five) would be that it is people’s tendency to experience negative emotions such as anxiety, anger, and sadness across a variety of situations. This definition might also include that it has a strong genetic component, remains fairly stable over time, and is positively correlated with the tendency to experience pain and other physical symptoms.

Students sometimes wonder why, when researchers want to understand a construct like self-esteem or neuroticism, they do not simply look it up in the dictionary. One reason is that many scientific constructs do not have counterparts in everyday language (e.g., working memory capacity). More important, researchers are in the business of developing definitions that are more detailed and precise—and that more accurately describe the way the world is—than the informal definitions in the dictionary. As we will see, they do this by proposing conceptual definitions, testing them empirically, and revising them as necessary. Sometimes they throw them out altogether. This is why the research literature often includes different conceptual definitions of the same construct. In some cases, an older conceptual definition has been replaced by a newer one that fits and works better. In others, researchers are still in the process of deciding which of various conceptual definitions is the best.

Operational Definitions

An operational definition is a definition of a variable in terms of precisely how it is to be measured. These measures generally fall into one of three broad categories. Self-report measures are those in which participants report on their own thoughts, feelings, and actions, as with the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (Rosenberg, 1965)[2]. Behavioral measures are those in which some other aspect of participants’ behavior is observed and recorded. This is an extremely broad category that includes the observation of people’s behavior both in highly structured laboratory tasks and in more natural settings. A good example of the former would be measuring working memory capacity using the backward digit span task. A good example of the latter is a famous operational definition of physical aggression from researcher Albert Bandura and his colleagues (Bandura, Ross, & Ross, 1961)[3]. They let each of several children play for 20 minutes in a room that contained a clown-shaped punching bag called a Bobo doll. They filmed each child and counted the number of acts of physical aggression the child committed. These included hitting the doll with a mallet, punching it, and kicking it. Their operational definition, then, was the number of these specifically defined acts that the child committed during the 20-minute period. Finally, physiological measures are those that involve recording any of a wide variety of physiological processes, including heart rate and blood pressure, galvanic skin response, hormone levels, and electrical activity and blood flow in the brain.

For any given variable or construct, there will be multiple operational definitions. Stress is a good example. A rough conceptual definition is that stress is an adaptive response to a perceived danger or threat that involves physiological, cognitive, affective, and behavioral components. But researchers have operationally defined it in several ways. The Social Readjustment Rating Scale (Holmes & Rahe, 1967)[4] is a self-report questionnaire on which people identify stressful events that they have experienced in the past year and assigns points for each one depending on its severity. For example, a man who has been divorced (73 points), changed jobs (36 points), and had a change in sleeping habits (16 points) in the past year would have a total score of 125. The Hassles and Uplifts Scale (Delongis, Coyne, Dakof, Folkman & Lazarus, 1982) [5] is similar but focuses on everyday stressors like misplacing things and being concerned about one’s weight. The Perceived Stress Scale (Cohen, Kamarck, & Mermelstein, 1983) [6] is another self-report measure that focuses on people’s feelings of stress (e.g., “How often have you felt nervous and stressed?”). Researchers have also operationally defined stress in terms of several physiological variables including blood pressure and levels of the stress hormone cortisol.

When psychologists use multiple operational definitions of the same construct—either within a study or across studies—they are using converging operations. The idea is that the various operational definitions are “converging” or coming together on the same construct. When scores based on several different operational definitions are closely related to each other and produce similar patterns of results, this constitutes good evidence that the construct is being measured effectively and that it is useful. The various measures of stress, for example, are all correlated with each other and have all been shown to be correlated with other variables such as immune system functioning (also measured in a variety of ways) (Segerstrom & Miller, 2004)[7]. This is what allows researchers eventually to draw useful general conclusions, such as “stress is negatively correlated with immune system functioning,” as opposed to more specific and less useful ones, such as “people’s scores on the Perceived Stress Scale are negatively correlated with their white blood counts.”

Levels of Measurement

The psychologist S. S. Stevens suggested that scores can be assigned to individuals in a way that communicates more or less quantitative information about the variable of interest (Stevens, 1946)[8]. For example, the officials at a 100-m race could simply rank order the runners as they crossed the finish line (first, second, etc.), or they could time each runner to the nearest tenth of a second using a stopwatch (11.5 s, 12.1 s, etc.). In either case, they would be measuring the runners’ times by systematically assigning scores to represent those times. But while the rank ordering procedure communicates the fact that the second-place runner took longer to finish than the first-place finisher, the stopwatch procedure also communicates how much longer the second-place finisher took. Stevens actually suggested four different levels of measurement (which he called “scales of measurement”) that correspond to four types of information that can be communicated by a set of scores, and the statistical procedures that can be used with the information.

The nominal level of measurement is used for categorical variables and involves assigning scores that are category labels. Category labels communicate whether any two individuals are the same or different in terms of the variable being measured. For example, if you ask your participants about their marital status, you are engaged in nominal-level measurement. Or if you ask your participants to indicate which of several ethnicities they identify themselves with, you are again engaged in nominal-level measurement. The essential point about nominal scales is that they do not imply any ordering among the responses. For example, when classifying people according to their favorite color, there is no sense in which green is placed “ahead of” blue. Responses are merely categorized. Nominal scales thus embody the lowest level of measurement[9].

The remaining three levels of measurement are used for quantitative variables. The ordinal level of measurement involves assigning scores so that they represent the rank order of the individuals. Ranks communicate not only whether any two individuals are the same or different in terms of the variable being measured but also whether one individual is higher or lower on that variable. For example, a researcher wishing to measure consumers’ satisfaction with their microwave ovens might ask them to specify their feelings as either “very dissatisfied,” “somewhat dissatisfied,” “somewhat satisfied,” or “very satisfied.” The items in this scale are ordered, ranging from least to most satisfied. This is what distinguishes ordinal from nominal scales. Unlike nominal scales, ordinal scales allow comparisons of the degree to which two individuals rate the variable. For example, our satisfaction ordering makes it meaningful to assert that one person is more satisfied than another with their microwave ovens. Such an assertion reflects the first person’s use of a verbal label that comes later in the list than the label chosen by the second person.

On the other hand, ordinal scales fail to capture important information that will be present in the other levels of measurement we examine. In particular, the difference between two levels of an ordinal scale cannot be assumed to be the same as the difference between two other levels (just like you cannot assume that the gap between the runners in first and second place is equal to the gap between the runners in second and third place). In our satisfaction scale, for example, the difference between the responses “very dissatisfied” and “somewhat dissatisfied” is probably not equivalent to the difference between “somewhat dissatisfied” and “somewhat satisfied.” Nothing in our measurement procedure allows us to determine whether the two differences reflect the same difference in psychological satisfaction. Statisticians express this point by saying that the differences between adjacent scale values do not necessarily represent equal intervals on the underlying scale giving rise to the measurements. (In our case, the underlying scale is the true feeling of satisfaction, which we are trying to measure.)

The interval level of measurement involves assigning scores using numerical scales in which intervals have the same interpretation throughout. As an example, consider either the Fahrenheit or Celsius temperature scales. The difference between 30 degrees and 40 degrees represents the same temperature difference as the difference between 80 degrees and 90 degrees. This is because each 10-degree interval has the same physical meaning (in terms of the kinetic energy of molecules).

Interval scales are not perfect, however. In particular, they do not have a true zero point even if one of the scaled values happens to carry the name “zero.” The Fahrenheit scale illustrates the issue. Zero degrees Fahrenheit does not represent the complete absence of temperature (the absence of any molecular kinetic energy). In reality, the label “zero” is applied to its temperature for quite accidental reasons connected to the history of temperature measurement. Since an interval scale has no true zero point, it does not make sense to compute ratios of temperatures. For example, there is no sense in which the ratio of 40 to 20 degrees Fahrenheit is the same as the ratio of 100 to 50 degrees; no interesting physical property is preserved across the two ratios. After all, if the “zero” label were applied at the temperature that Fahrenheit happens to label as 10 degrees, the two ratios would instead be 30 to 10 and 90 to 40, no longer the same! For this reason, it does not make sense to say that 80 degrees is “twice as hot” as 40 degrees. Such a claim would depend on an arbitrary decision about where to “start” the temperature scale, namely, what temperature to call zero (whereas the claim is intended to make a more fundamental assertion about the underlying physical reality).

In psychology, the intelligence quotient (IQ) is often considered to be measured at the interval level. While it is technically possible to receive a score of 0 on an IQ test, such a score would not indicate the complete absence of IQ. Moreover, a person with an IQ score of 140 does not have twice the IQ of a person with a score of 70. However, the difference between IQ scores of 80 and 100 is the same as the difference between IQ scores of 120 and 140.

Finally, the ratio level of measurement involves assigning scores in such a way that there is a true zero point that represents the complete absence of the quantity. Height measured in meters and weight measured in kilograms are good examples. So are counts of discrete objects or events such as the number of siblings one has or the number of questions a student answers correctly on an exam. You can think of a ratio scale as the three earlier scales rolled up in one. Like a nominal scale, it provides a name or category for each object (the numbers serve as labels). Like an ordinal scale, the objects are ordered (in terms of the ordering of the numbers). Like an interval scale, the same difference at two places on the scale has the same meaning. However, in addition, the same ratio at two places on the scale also carries the same meaning (see Table 4.1).

The Fahrenheit scale for temperature has an arbitrary zero point and is therefore not a ratio scale. However, zero on the Kelvin scale is absolute zero. This makes the Kelvin scale a ratio scale. For example, if one temperature is twice as high as another as measured on the Kelvin scale, then it has twice the kinetic energy of the other temperature.

Another example of a ratio scale is the amount of money you have in your pocket right now (25 cents, 50 cents, etc.). Money is measured on a ratio scale because, in addition to having the properties of an interval scale, it has a true zero point: if you have zero money, this actually implies the absence of money. Since money has a true zero point, it makes sense to say that someone with 50 cents has twice as much money as someone with 25 cents.

Stevens’s levels of measurement are important for at least two reasons. First, they emphasize the generality of the concept of measurement. Although people do not normally think of categorizing or ranking individuals as measurement, in fact, they are as long as they are done so that they represent some characteristic of the individuals. Second, the levels of measurement can serve as a rough guide to the statistical procedures that can be used with the data and the conclusions that can be drawn from them. With nominal-level measurement, for example, the only available measure of central tendency is the mode. With ordinal-level measurement, the median or mode can be used as indicators of central tendency. Interval and ratio-level measurement are typically considered the most desirable because they permit for any indicators of central tendency to be computed (i.e., mean, median, or mode). Also, ratio-level measurement is the only level that allows meaningful statements about ratios of scores. Once again, one cannot say that someone with an IQ of 140 is twice as intelligent as someone with an IQ of 70 because IQ is measured at the interval level, but one can say that someone with six siblings has twice as many as someone with three because number of siblings is measured at the ratio level.

| Level of Measurement | Category labels | Rank order | Equal intervals | True zero |

| NOMINAL | X | |||

| ORDINAL | X | X | ||

| INTERVAL | X | X | X | |

| RATIO | X | X | X | X |

- Costa, P. T., Jr., & McCrae, R. R. (1992). Normal personality assessment in clinical practice: The NEO Personality Inventory. Psychological Assessment, 4, 5–13. ↵

- Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press ↵

- Bandura, A., Ross, D., & Ross, S. A. (1961). Transmission of aggression through imitation of aggressive models. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 63, 575–582. ↵

- Holmes, T. H., & Rahe, R. H. (1967). The Social Readjustment Rating Scale. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 11(2), 213-218. ↵

- Delongis, A., Coyne, J. C., Dakof, G., Folkman, S., & Lazarus, R. S. (1982). Relationships of daily hassles, uplifts, and major life events to health status. Health Psychology, 1(2), 119-136. ↵

- Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., & Mermelstein, R. (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24, 386-396. ↵

- Segerstrom, S. E., & Miller, G. E. (2004). Psychological stress and the human immune system: A meta-analytic study of 30 years of inquiry. Psychological Bulletin, 130, 601–630. ↵

- Stevens, S. S. (1946). On the theory of scales of measurement. Science, 103, 677–680. ↵

- Levels of Measurement. Retrieved from http://wikieducator.org/Introduction_to_Research_Methods_In_Psychology/Theories_and_Measurement/Levels_of_Measurement ↵

Is the assignment of scores to individuals so that the scores represent some characteristic of the individuals.

Learning Objectives

- Describe useful strategies to employ when searching for literature

- Identify how to narrow down search results to the most relevant sources

One of the drawbacks (or joys, depending on your perspective) of being a researcher in the 21st century is that we can do much of our work without ever leaving the comfort of our recliners. This is certainly true of familiarizing yourself with the literature. Most libraries offer incredible online search options and access to important databases of academic journal articles.

A literature search usually follows these steps:

- Building search queries

- Finding the right database

- Skimming the abstracts of articles

- Looking at authors and journal names

- Examining references

- Searching for meta-analyses and systematic reviews

Step 1: Building a search query with keywords

What do you type when you are searching for something on Google? Are you a question-asker? Do you type in full sentences or just a few keywords? What you type into a database or search engine like Google is called a query. Well-constructed queries get you to the information you need faster, while unclear queries will force you to sift through dozens of irrelevant articles before you find the ones you want.

The words you use in your search query will determine the results you get. Unfortunately, different studies often use different words to mean the same thing. A study may describe its topic as substance abuse, rather than addiction. Think of different keywords that are relevant to your topic area and write them down. Often in social work research, there is a bit of jargon to learn in crafting your search queries. For example, if you wanted to learn more about people of low-income households who do not have access to a bank account, it may be helpful to include the jargon term "unbanked" in your search query. If you wanted to learn about children who take on parental roles in families, you may need to include “parentification” as part of your search query. As undergraduate researchers, you are not expected to know these terms ahead of time. Instead, start with the keywords you already know. Once you read more about your topic, start including new keywords that will return the most relevant search results for you.

Google is a “natural language” search engine, which means it tries to use its knowledge of how people to talk to better understand your query. Google’s academic database, Google Scholar, incorporates that same approach. However, other databases that are important for social work research—such as Academic Search Complete, PSYCinfo, and PubMed—will not return useful results if you ask a question, type a sentence, or use a phrase as your search query. Unlike Google Scholar, these databases are best used by typing in keywords. Instead of typing “the effects of cocaine addiction on the quality of parenting,” you might type in “cocaine AND parenting” or “addiction AND child development.” Note: you would not actually use the quotation marks in your search query for these examples.

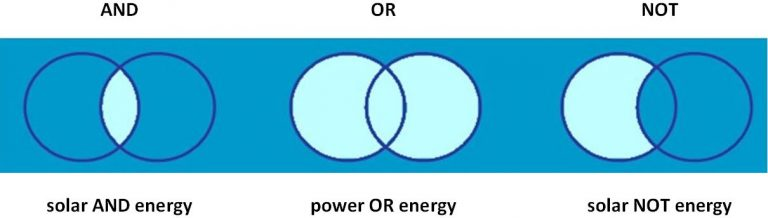

These operators (AND, OR, NOT) are part of what is called Boolean searching. Boolean searching works like a simple computer program. Your search query is made up of words connected by operators. Searching for “cocaine AND parenting” returns articles that mention both cocaine and parenting. There are lots of articles on cocaine and lots of articles on parenting, but fewer articles that discuss both topics together. In this way, the AND operator reduces the number of results you will get from your search query because both terms must be present. The NOT operator also reduces the number of results you get from your query. For example, perhaps you wanted to exclude issues related to pregnancy. Searching for “cocaine AND parenting NOT pregnancy” would exclude articles that mentioned pregnancy from your results. Conversely, the OR operator would increase the number of results you get from your query. For example, searching for “cocaine OR parenting” would return not only articles that mentioned both words but also those that mentioned only one of your two search terms. This relationship is visualized in Figure 2.1 below.

As my students have said in the past, probably the most frustrating part about literature searching is looking at the number of search results for your query. How could anyone be expected to look at hundreds of thousands of articles on a topic? Don’t worry. You don’t have to read all those articles to know enough about your topic area to produce a good research study. A good search query should bring you to at least a few relevant articles to your topic, which is more than enough to get you started. However, an excellent search query can narrow down your results to a much smaller number of articles, all of which are specifically focused on your topic area. Here are some tips for reducing the number of articles in your topic area:

- Use quotation marks to indicate exact phrases, like “mental health” or “substance abuse.”

- Search for your keywords in the ABSTRACT. A lot of your results may be from articles about irrelevant topics simply that mention your search term once. If your topic isn’t in the abstract, chances are the article isn’t relevant. You can be even more restrictive and search for your keywords in the TITLE. Academic databases provide these options in their advanced search tools.

- Use multiple keywords in the same query. Simply adding “addiction” onto a search for “substance abuse” will narrow down your results considerably.

- Use a SUBJECT heading like “substance abuse” to get results from authors who have tagged their articles as addressing the topic of substance abuse. Subject headings are likely to not have all the articles on a topic but are a good place to start.

- Narrow down the years of your search. Unless you are gathering historical information about a topic, you are unlikely to find articles older than 10-15 years to be useful. They are less useful because they no longer tell you the current knowledge on a topic. All databases have options to narrow your results down by year.

- Talk to a librarian. They are professional knowledge-gatherers, and there is often a librarian assigned to your department. Their job is to help you find what you need to know.

Step 2: Finding the right database

The four biggest databases you will probably use for finding academic journal articles relevant to social work are: Google Scholar, Academic Search Complete, PSYCinfo, and PubMed. Each has distinct advantages and disadvantages.

Because Google Scholar is a natural language search engine, you are more likely to get what you want without having to fuss with wording. It can be linked via Library Links to your university login, allowing you to access journal articles with one click on the Google Scholar page. Google Scholar also allows you to save articles in folders and provides a (somewhat correct) APA citation for each article. Google Scholar will automatically display not only journal articles, but also books, government and foundation reports, and gray literature, so you need to make sure that the source you are using is reputable. Look for the advanced search feature to narrow down your results further.

Academic Search Complete is available through your school’s library, usually under page titled databases. It is similar to Google Scholar in its breadth, as it contains a number of smaller databases from a variety of social science disciplines (including Social Work Abstracts). You have to use Boolean searching techniques, and there are a number of advanced search features to further narrow down your results.

PSYCinfo and PubMed focus on specific disciplines. PSYCinfo indexes articles on psychology, and PubMed indexes articles related to medical science. Because these databases are more narrowly targeted, you are more likely to get the specific psychological or medical knowledge you desire. If you were to use a more general search engine like Google Scholar, you may get more irrelevant results. Finally, it is worth mentioning that many university libraries have a meta-search engine which searches all the databases to which they have access.

Step 3: Skimming abstracts and downloading articles

Once you’ve settled on your search query and database, you should start to see articles that might be relevant to your topic. Rather than read every article, skim through the abstract to judge whether this article is relevant to your specific topic. If you like the article, make sure to download the full text PDF to your computer so you can read it later. Part of the tuition and fees your university charges you goes to paying major publishers of academic journals for the privilege of accessing their articles. Because access fees are incredibly costly, your school likely does not pay for access to all the journals in the world. While you are in school, you should never have to pay for access to an academic journal article. Instead, if your school does not subscribe to a journal you need to read, try using inter-library loan to get the article. On your university library’s homepage, there is likely a link to inter-library loan. Just enter the information for your article (e.g. author, publication year, title), and a librarian will work with librarians at other schools to get you the PDF of the article that you need. After you leave school, getting a PDF of an article becomes more challenging. However, you can always ask an author for a copy of their article. They will usually be happy to hear someone is interested in reading and using their work.

What do you do with all of those PDFs? I usually keep mine in folders on my cloud storage drive, arranged by topic. For those who are more ambitious, you may want to use a reference manager like Mendeley or RefWorks, which can help keep your sources and notes organized. At the very least, take notes on each article and think about how it might be of use in your study.

Step 4: Searching for author and journal names

As you scroll through the list of articles in your search results, you should begin to notice that certain authors appear more than once. If you find an author that has written multiple articles on your topic, consider searching the AUTHOR field for that particular author. You can also search the web for that author’s Curriculum Vitae or CV (an academic resume) that will list their publications. Many authors maintain personal websites or host their CV on their university department’s webpage. Just type in their name and “CV” into a search engine. For example, you may find Michael Sherraden’s name often if your search terms are about assets and poverty. You can find his CV on the Washington University of St. Louis website.

You can also narrow down your results by journal name. As you are scrolling, you should also notice that many of the articles you’ve skimmed come from the same journals. Searching with that journal name in the JOURNAL field will allow you to narrow down your results to just that journal. For example, if you are searching for articles related to values and ethics in social work, you might want to search within the Journal of Social Work Values and Ethics. You can also navigate to the journal’s webpage and browse the abstracts of the latest issues.

Step 5: Examining references

As you begin to read your articles, you’ll notice that the authors cite additional articles that are likely relevant to your topic area. This is called archival searching. Unfortunately, this process will only allow you to see relevant articles from before the publication date. That is, the reference section of an article from 2014 will only have references from pre-2014. You can use Google Scholar’s “cited by” feature to do a future-looking archival search. Look up an article on Google Scholar and click the “cited by” link. This is a list of all the articles that cite the article you just read. Google Scholar even allows you to search within the “cited by” articles to narrow down ones that are most relevant to your topic area. For a brief discussion about archival searching check out this article by Hammond & Brown (2008): http://www.infotoday.com/cilmag/may08/Hammond_Brown.shtml. [2]

Step 6: Searching for systematic reviews and other sources

Another way to save time in literature searching is to look for articles that synthesize the results of other articles. Systematic reviews provide a summary of the existing literature on a topic. If you find one on your topic, you will be able to read one person’s summary of the literature and go deeper by reading their references. Similarly, meta-analyses and meta-syntheses have long reference lists that are useful for finding additional sources on a topic. They use data from each article to run their own quantitative or qualitative data analysis. In this way, meta-analyses and meta-syntheses provide a more comprehensive overview of a topic. To find these kinds of articles, include the term “meta-analysis,” “meta-synthesis,” or “systematic review” to your search terms. Another way to find systematic reviews is through the Cochrane Collaboration or Campbell Collaboration. These institutions are dedicated to producing systematic reviews for the purposes of evidence-based practice.

Putting it all together

Familiarizing yourself with research that has already been conducted on your topic is one of the first stages of conducting a research project and is crucial for coming up with a good research design. But where to start? How to start? Earlier in this chapter you learned about some of the most common databases that house information about published social work research. As you search for literature, you may have to be fairly broad in your search for articles. Let’s walk through an example.

Dr. Blackstone, one of the original authors of this textbook, relates an example from her research methods class: On a college campus nearby, much to the chagrin of a group of student smokers, smoking was recently banned. These students were so upset by the idea that they would no longer be allowed to smoke on university grounds that they staged several smoke-outs during which they gathered in populated areas around campus and enjoyed a puff or two together.

A student in her research methods class wanted to understand what motivated this group of students to engage in activism centered on what she perceived to be, in this age of smoke-free facilities, a relatively deviant act. Were the protesters otherwise politically active? How much effort and coordination had it taken to organize the smoke-outs? The student researcher began her research by attempting to familiarize herself with the literature on her topic, yet her search in Academic Search Complete for “college student activist smoke-outs,” yielded no results. Concluding there was no prior research on her topic, she informed her professor that she would not be able to write the required literature review since there was no literature for her to review. How do you suppose her professor responded to this news? What went wrong with this student’s search for literature?

In her first attempt, the student had been too narrow in her search for articles. But did that mean she was off the hook for completing a literature review? Absolutely not. Instead, she went back to Academic Search Complete and searched again using different combinations of search terms. Rather than searching for “college student activist smoke-outs” she tried searching for "college student activism," among other sets of terms. This time, her search yielded many related articles. Of course, they were not focused on pro-smoking activist efforts, but they were focused on her population of interest, college students, and on her broad topic of interest, activism. Her professor suggested that reading articles on college student activism might illuminate what other researchers have found in terms of motivational factors that influence college students to become involved in activism. Her professor also suggested she could switch up her search terms and look for research on activism about other sorts of deviant activities, such as marijuana use or veganism. In other words, she needed to be broader in her search for articles.

While this student found success by broadening her search for articles, her reading of those articles needed to be narrower than her search. Once she identified a set of articles to review by searching broadly, it was time to remind herself of her specific research focus: college student activist smoke-outs. Keeping in mind her particular research interest while reviewing the literature gave her the chance to think about how the theories and findings covered in prior studies might or might not apply to her particular point of focus. For example, theories on what motivates activists to get involved might tell her something about the likely reasons the students she planned to study got involved. At the same time, those theories might not cover all the particulars of student participation in smoke-outs. Thinking about the different theories then gave the student the opportunity to focus her research plans and develop a few hypotheses about her anticipated findings.

Key Takeaways

- When identifying and reading relevant literature, be broad in your search for articles but be narrow in your reading of articles.

- Conducting a literature search involves the skillful use of keywords to find relevant articles.

- It is important to narrow down the number of articles in your search results to only those articles that are most relevant to your inquiry.

Glossary

Query- search terms used in a database to find sources

Image Attributions

Magnifying glass google by Simon CC-0

Librarian at the Card Files at Senior High School in New Ulm Minnesota by David Rees CC-0

No smoking by OpenIcons CC-0

Describes the behaviors and internal processes that make up a psychological construct, along with how it relates to other variables.

Measures in which participants report on their own thoughts, feelings, and actions.

Measures in which some other aspect of participants’ behavior is observed and recorded.

Measures that involve recording any of a wide variety of physiological processes, including heart rate and blood pressure, galvanic skin response, hormone levels, and electrical activity and blood flow in the brain.

When psychologists use multiple operational definitions of the same construct—either within a study or across studies.

Learning Objectives

- Define and describe informed consent

- Identify the unique concerns related to studying vulnerable populations

- Differentiate between anonymity and confidentiality

- Explain the ethical responsibilities of social workers conducting research

As should be clear by now, conducting research on humans presents a number of unique ethical considerations. Human research subjects must be given the opportunity to consent to their participation, after being fully informed of the study's risks, benefits, and purpose. Further, subjects’ identities and the information they share should be protected by researchers. Of course, the definitions of consent and identity protection may vary by individual researcher, institution, or academic discipline. In section 5.1, we examined the role that institutions play in shaping research ethics. In this section, we’ll look at a few specific topics that individual researchers and social workers must consider before conducting research with human subjects.

Informed consent

All social work research projects involve the voluntary participation of all human subjects. In other words, we cannot force anyone to participate in our research without their knowledge and consent, unlike the experiment in Truman Show. Researchers must therefore design procedures to obtain subjects’ informed consent to participate in their research. Informed consent is defined as a subject’s voluntary agreement to participate in research based on a full understanding of the research and of the possible risks and benefits involved. Although it sounds simple, ensuring that one has actually obtained informed consent is a much more complex process than you might initially presume.

The first requirement to obtain informed consent is that participants may neither waive nor even appear to waive any of their legal rights. In addition, if something were to go wrong during their participation in research, participants cannot release the researcher, the researcher's sponsor, or any institution from any legal liability (USDHHS, 2009). [3] Unlike biomedical research, for example, social work research does not typically involve asking subjects to place themselves at risk of physical harm. Because of this, social work researchers often do not have to worry about potential liability, however their research may involve other types of risks.

For example, what if a social work researcher fails to sufficiently conceal the identity of a subject who admits to participating in a local swinger’s club? In this case, a violation of confidentiality may negatively affect the participant’s social standing, marriage, custody rights, or employment. Social work research may also involve asking about intimately personal topics, such as trauma or suicide that may be difficult for participants to discuss. Participants may re-experience traumatic events and symptoms when they participate in your study. Even after fully informing the participants of all risks before they consent to the research process, there is the possibility of raising difficult topics that prove overwhelming for participants. In cases like these, it is important for a social work researcher to have a plan to provide supports, such as referrals to community counseling or even calling the police if the participant is a danger to themselves or others.

It is vital that social work researchers craft their consent forms to fully explain their mandatory reporting duties and ensure that subjects understand the terms before participating. Researchers should also emphasize to participants that they can stop the research process at any time or decide to withdraw from the research study for any reason. Importantly, it is not the job of the social work researcher to act as a clinician to the participant. While a supportive role is certainly appropriate for someone experiencing a mental health crisis, social workers must ethically avoid dual roles. Referring a participant in crisis to other mental health professionals who may be better able to help them is preferred.

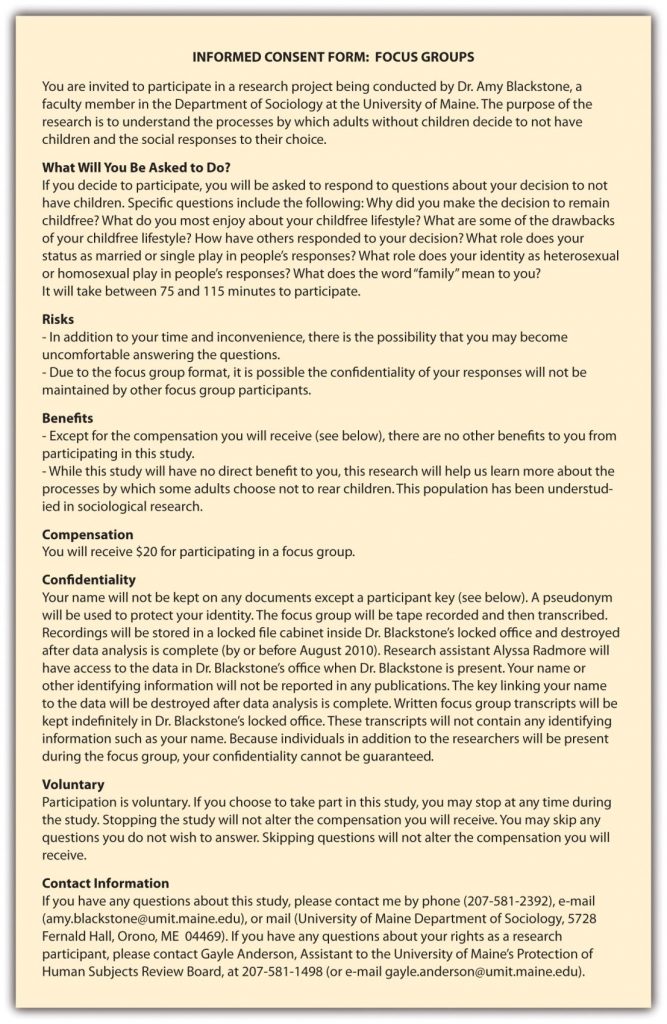

In addition to legal issues, most IRBs are also concerned with details of the research, including: the purpose of the study, possible benefits of participation, and most importantly, potential risks of participation. Further, researchers must describe how they will protect subjects’ identities, all details regarding data collection and storage, and provide a contact reached for additional information about the study and the subjects’ rights. All of this information is typically shared in an informed consent form that researchers provide to subjects. In some cases, subjects are asked to sign the consent form indicating that they have read it and fully understand its contents. In other cases, subjects are simply provided a copy of the consent form and researchers are responsible for making sure that subjects have read and understand the form before proceeding with any kind of data collection. Figure 5.1 showcases a sample informed consent form taken from a research project on child-free adults. Note that this consent form describes a risk that may be unique to the particular method of data collection being employed: focus groups.

When preparing to obtain informed consent, it is important to consider that not all potential research subjects are considered equally competent or legally allowed to consent to participate in research. Subjects from vulnerable populations may be at risk of experiencing undue influence or coercion. [5] The rules for consent are more stringent for vulnerable populations. For example, minors must have the consent of a legal guardian in order to participate in research. In some cases, the minors themselves are also asked to participate in the consent process by signing special, age-appropriate consent forms. Vulnerable populations raise many unique concerns because they may not be able to fully consent to research participation. Researchers must be concerned with the potential for underrepresentation of vulnerable groups in studies. On one hand, researchers must ensure that their procedures to obtain consent are not coercive, as the informed consent process can be more rigorous for these groups. On the other hand, researchers must also work to ensure members of vulnerable populations are not excluded from participation simply because of their vulnerability or the complexity of obtaining their consent. While there is no easy solution to this double-edged sword, an awareness of the potential concerns associated with research on vulnerable populations is important for identifying whatever solution is most appropriate for a specific case.

Protection of identities

As mentioned earlier, the informed consent process requires researchers to outline how they will protect the identities of subjects. This aspect of the process, however, is one of the most commonly misunderstood aspects of research.

In protecting subjects’ identities, researchers typically promise to maintain either the anonymity or confidentiality of their research subjects. Anonymity is the more stringent of the two. When a researcher promises anonymity to participants, not even the researcher is able to link participants’ data with their identities. Anonymity may be impossible for some social work researchers to promise because several of the modes of data collection that social workers employ. Face-to-face interviewing means that subjects will be visible to researchers and will hold a conversation, making anonymity impossible. In other cases, the researcher may have a signed consent form or obtain personal information on a survey and will therefore know the identities of their research participants. In these cases, a researcher should be able to at least promise confidentiality to participants.

Offering confidentiality means that some of the subjects' identifying information is known and may be kept, but only the researcher can link identity to data with the promise to keep this information private. Confidentiality in research and clinical practice are similar in that you know who your clients are, but others do not, and you promise to keep their information and identity private. As you can see under the “Risks” section of the consent form in Figure 5.1, sometimes it is not even possible to promise that a subject’s confidentiality will be maintained. This is the case if data collection takes place in public or in the presence of other research participants, like in a focus group study. Social workers also cannot promise confidentiality in cases where research participants pose an imminent danger to themselves or others, or if they disclose abuse of children or other vulnerable populations. These situations fall under a social worker’s duty to report, which requires the researcher to prioritize their legal obligations over participant confidentiality.

Protecting research participants’ identities is not always a simple prospect, especially for those conducting research on stigmatized groups or illegal behaviors. Sociologist Scott DeMuth learned how difficult this task was while conducting his dissertation research on a group of animal rights activists. As a participant observer, DeMuth knew the identities of his research subjects. When some of his research subjects vandalized facilities and removed animals from several research labs at the University of Iowa, a grand jury called on Mr. DeMuth to reveal the identities of the participants in the raid. When DeMuth refused to do so, he was jailed briefly and then charged with conspiracy to commit animal enterprise terrorism and cause damage to the animal enterprise (Jaschik, 2009). [6]

Publicly, DeMuth’s case raised many of the same questions as Laud Humphreys’ work 40 years earlier. What do social scientists owe the public? By protecting his research subjects, is Mr. DeMuth harming those whose labs were vandalized? Is he harming the taxpayers who funded those labs, or is it more important that he emphasize the promise of confidentiality to his research participants? DeMuth’s case also sparked controversy among academics, some of whom thought that as an academic himself, DeMuth should have been more sympathetic to the plight of the faculty and students who lost years of research as a result of the attack on their labs. Many others stood by DeMuth, arguing that the personal and academic freedom of scholars must be protected whether we support their research topics and subjects or not. DeMuth’s academic adviser even created a new group, Scholars for Academic Justice (http://sajumn.wordpress.com), to support DeMuth and other academics who face persecution or prosecution as a result of the research they conduct. What do you think? Should DeMuth have revealed the identities of his research subjects? Why or why not?

Disciplinary considerations

Often times, specific disciplines will provide their own set of guidelines for protecting research subjects and, more generally, for conducting ethical research. For social workers, the National Association of Social Workers (NASW) Code of Ethics section 5.02 describes the responsibilities of social workers in conducting research. Summarized below, these guidelines outline that as a representative of the social work profession, it is your responsibility to conduct to conduct and use research in an ethical manner.

A social worker should:

- Monitor and evaluate policies, programs, and practice interventions

- Contribute to the development of knowledge through research

- Keep current with the best available research evidence to inform practice

- Ensure voluntary and fully informed consent of all participants

- Avoid engaging in any deception in the research process

- Allow participants to withdraw from the study at any time

- Provide access for participants to appropriate supportive services

- Protect research participants from harm

- Maintain confidentiality

- Report findings accurately

- Disclose any conflicts of interest

Key Takeaways

- Researchers must obtain the informed consent of the people who participate in their research.

- Social workers must take steps to minimize the harms that could arise during the research process.

- If a researcher promises anonymity, they cannot link individual participants with their data.

- If a researcher promises confidentiality, they promise not to reveal the identities of research participants, even though they can link individual participants with their data.

- The NASW Code of Ethics includes specific responsibilities for social work researchers.

Glossary

Anonymity- the identity of research participants is not known to researchers

Confidentiality- identifying information about research participants is known to the researchers but is not divulged to anyone else

Informed consent- a research subject’s voluntary agreement to participate in a study based on a full understanding of the study and of the possible risks and benefits involved

A measurement used for categorical variables and involves assigning scores that are category labels.

A measurement that involves assigning scores so that they represent the rank order of the individuals.

A measurement that involves assigning scores using numerical scales in which intervals have the same interpretation throughout.

A measurement that involves assigning scores in such a way that there is a true zero point that represents the complete absence of the quantity.