41 Setting Up a Factorial Experiment

Learning Objectives

- Explain why researchers often include multiple independent variables in their studies.

- Define factorial design, and use a factorial design table to represent and interpret simple factorial designs.

Just as it is common for studies in psychology to include multiple levels of a single independent variable (placebo, new drug, old drug), it is also common for them to include multiple independent variables. Schnall and her colleagues studied the effect of both disgust and private body consciousness in the same study. Researchers’ inclusion of multiple independent variables in one experiment is further illustrated by the following actual titles from various professional journals:

- The Effects of Temporal Delay and Orientation on Haptic Object Recognition

- Opening Closed Minds: The Combined Effects of Intergroup Contact and Need for Closure on Prejudice

- Effects of Expectancies and Coping on Pain-Induced Intentions to Smoke

- The Effect of Age and Divided Attention on Spontaneous Recognition

- The Effects of Reduced Food Size and Package Size on the Consumption Behavior of Restrained and Unrestrained Eaters

Just as including multiple levels of a single independent variable allows one to answer more sophisticated research questions, so too does including multiple independent variables in the same experiment. For example, instead of conducting one study on the effect of disgust on moral judgment and another on the effect of private body consciousness on moral judgment, Schnall and colleagues were able to conduct one study that addressed both questions. But including multiple independent variables also allows the researcher to answer questions about whether the effect of one independent variable depends on the level of another. This is referred to as an interaction between the independent variables. Schnall and her colleagues, for example, observed an interaction between disgust and private body consciousness because the effect of disgust depended on whether participants were high or low in private body consciousness. As we will see, interactions are often among the most interesting results in psychological research.

Factorial Designs

Overview

By far the most common approach to including multiple independent variables (which are often called factors) in an experiment is the factorial design. In a factorial design, each level of one independent variable is combined with each level of the others to produce all possible combinations. Each combination, then, becomes a condition in the experiment. Imagine, for example, an experiment on the effect of cell phone use (yes vs. no) and time of day (day vs. night) on driving ability. This is shown in the factorial design table in Figure 9.1. The columns of the table represent cell phone use, and the rows represent time of day. The four cells of the table represent the four possible combinations or conditions: using a cell phone during the day, not using a cell phone during the day, using a cell phone at night, and not using a cell phone at night. This particular design is referred to as a 2 × 2 (read “two-by-two”) factorial design because it combines two variables, each of which has two levels.

If one of the independent variables had a third level (e.g., using a handheld cell phone, using a hands-free cell phone, and not using a cell phone), then it would be a 3 × 2 factorial design, and there would be six distinct conditions. Notice that the number of possible conditions is the product of the numbers of levels. A 2 × 2 factorial design has four conditions, a 3 × 2 factorial design has six conditions, a 4 × 5 factorial design would have 20 conditions, and so on. Also notice that each number in the notation represents one factor, one independent variable. So by looking at how many numbers are in the notation, you can determine how many independent variables there are in the experiment. 2 x 2, 3 x 3, and 2 x 3 designs all have two numbers in the notation and therefore all have two independent variables. The numerical value of each of the numbers represents the number of levels of each independent variable. A 2 means that the independent variable has two levels, a 3 means that the independent variable has three levels, a 4 means it has four levels, etc. To illustrate a 3 x 3 design has two independent variables, each with three levels, while a 2 x 2 x 2 design has three independent variables, each with two levels.

In principle, factorial designs can include any number of independent variables with any number of levels. For example, an experiment could include the type of psychotherapy (cognitive vs. behavioral), the length of the psychotherapy (2 weeks vs. 2 months), and the sex of the psychotherapist (female vs. male). This would be a 2 × 2 × 2 factorial design and would have eight conditions. Figure 9.2 shows one way to represent this design. In practice, it is unusual for there to be more than three independent variables with more than two or three levels each. This is for at least two reasons: For one, the number of conditions can quickly become unmanageable. For example, adding a fourth independent variable with three levels (e.g., therapist experience: low vs. medium vs. high) to the current example would make it a 2 × 2 × 2 × 3 factorial design with 24 distinct conditions. Second, the number of participants required to populate all of these conditions (while maintaining a reasonable ability to detect a real underlying effect) can render the design unfeasible (for more information, see the discussion about the importance of adequate statistical power in Chapter 13). As a result, in the remainder of this section, we will focus on designs with two independent variables. The general principles discussed here extend in a straightforward way to more complex factorial designs.

Assigning Participants to Conditions

Recall that in a simple between-subjects design, each participant is tested in only one condition. In a simple within-subjects design, each participant is tested in all conditions. In a factorial experiment, the decision to take the between-subjects or within-subjects approach must be made separately for each independent variable. In a between-subjects factorial design, all of the independent variables are manipulated between subjects. For example, all participants could be tested either while using a cell phone or while not using a cell phone and either during the day or during the night. This would mean that each participant would be tested in one and only one condition. In a within-subjects factorial design, all of the independent variables are manipulated within subjects. All participants could be tested both while using a cell phone and while not using a cell phone and both during the day and during the night. This would mean that each participant would need to be tested in all four conditions. The advantages and disadvantages of these two approaches are the same as those discussed in Chapter 5. The between-subjects design is conceptually simpler, avoids order/carryover effects, and minimizes the time and effort of each participant. The within-subjects design is more efficient for the researcher and controls extraneous participant variables.

Since factorial designs have more than one independent variable, it is also possible to manipulate one independent variable between subjects and another within subjects. This is called a mixed factorial design. For example, a researcher might choose to treat cell phone use as a within-subjects factor by testing the same participants both while using a cell phone and while not using a cell phone (while counterbalancing the order of these two conditions). But they might choose to treat time of day as a between-subjects factor by testing each participant either during the day or during the night (perhaps because this only requires them to come in for testing once). Thus each participant in this mixed design would be tested in two of the four conditions.

Regardless of whether the design is between subjects, within subjects, or mixed, the actual assignment of participants to conditions or orders of conditions is typically done randomly.

Non-Manipulated Independent Variables

In many factorial designs, one of the independent variables is a non-manipulated independent variable. The researcher measures it but does not manipulate it. The study by Schnall and colleagues is a good example. One independent variable was disgust, which the researchers manipulated by testing participants in a clean room or a messy room. The other was private body consciousness, a participant variable which the researchers simply measured. Another example is a study by Halle Brown and colleagues in which participants were exposed to several words that they were later asked to recall (Brown, Kosslyn, Delamater, Fama, & Barsky, 1999)[1]. The manipulated independent variable was the type of word. Some were negative health-related words (e.g., tumor, coronary), and others were not health related (e.g., election, geometry). The non-manipulated independent variable was whether participants were high or low in hypochondriasis (excessive concern with ordinary bodily symptoms). The result of this study was that the participants high in hypochondriasis were better than those low in hypochondriasis at recalling the health-related words, but they were no better at recalling the non-health-related words.

Such studies are extremely common, and there are several points worth making about them. First, non-manipulated independent variables are usually participant variables (private body consciousness, hypochondriasis, self-esteem, gender, and so on), and as such, they are by definition between-subjects factors. For example, people are either low in hypochondriasis or high in hypochondriasis; they cannot be tested in both of these conditions. Second, such studies are generally considered to be experiments as long as at least one independent variable is manipulated, regardless of how many non-manipulated independent variables are included. Third, it is important to remember that causal conclusions can only be drawn about the manipulated independent variable. For example, Schnall and her colleagues were justified in concluding that disgust affected the harshness of their participants’ moral judgments because they manipulated that variable and randomly assigned participants to the clean or messy room. But they would not have been justified in concluding that participants’ private body consciousness affected the harshness of their participants’ moral judgments because they did not manipulate that variable. It could be, for example, that having a strict moral code and a heightened awareness of one’s body are both caused by some third variable (e.g., neuroticism). Thus it is important to be aware of which variables in a study are manipulated and which are not.

Non-Experimental Studies With Factorial Designs

Thus far we have seen that factorial experiments can include manipulated independent variables or a combination of manipulated and non-manipulated independent variables. But factorial designs can also include only non-manipulated independent variables, in which case they are no longer experiments but are instead non-experimental in nature. Consider a hypothetical study in which a researcher simply measures both the moods and the self-esteem of several participants—categorizing them as having either a positive or negative mood and as being either high or low in self-esteem—along with their willingness to have unprotected sexual intercourse. This can be conceptualized as a 2 × 2 factorial design with mood (positive vs. negative) and self-esteem (high vs. low) as non-manipulated between-subjects factors. Willingness to have unprotected sex is the dependent variable.

Again, because neither independent variable in this example was manipulated, it is a non-experimental study rather than an experiment. (The similar study by MacDonald and Martineau [2002][2] was an experiment because they manipulated their participants’ moods.) This is important because, as always, one must be cautious about inferring causality from non-experimental studies because of the directionality and third-variable problems. For example, an effect of participants’ moods on their willingness to have unprotected sex might be caused by any other variable that happens to be correlated with their moods.

- Brown, H. D., Kosslyn, S. M., Delamater, B., Fama, A., & Barsky, A. J. (1999). Perceptual and memory biases for health-related information in hypochondriacal individuals. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 47, 67–78. ↵

- MacDonald, T. K., & Martineau, A. M. (2002). Self-esteem, mood, and intentions to use condoms: When does low self-esteem lead to risky health behaviors? Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 38, 299–306. ↵

Learning Objectives

- Reflect on how we know what to do as social workers

- Differentiate between micro-, meso-, and macro-level analysis

- Describe intuition, its purpose in social work, and its limitations

- Identify specific types of cognitive biases and how the influence thought

- Define scientific inquiry

What would you do?

Imagine you are a clinical social worker at a children’s mental health agency. Today, you receive a referral from your town’s middle school about a client who often skips school, gets into fights, and is disruptive in class. The school has suspended him and met with the parents multiple times. They report that they practice strict discipline at home, yet the client’s behavior has only gotten worse. When you arrive at the school to meet with the boy, you notice that he has difficulty maintaining eye contact with you, appears distracted, and has a few bruises on his legs. You also find out that he is a gifted artist, so you decide to paint and draw together while you assess him.

- Given the strengths and challenges you notice, what interventions would you select for this client and how would you know your interventions worked?

Imagine you are a social worker in an urban food desert, a geographic area in which there is no grocery store that sells fresh food. Many of your low-income clients live solely on food from the dollar store, convenience stores, or takeout, as they are unable to buy fresh food. You are becoming concerned about your clients’ health, as many of them are obese due to these conditions. Many of your clients survive on minimum wage jobs or Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits and end up relying on food pantries when their money runs out towards the end of the month. You have spent the past month building a coalition composed of members from your community, including non-profit agencies, religious groups, and healthcare workers to lobby your city council.

- How should your group address the issue of food deserts in your community? What intervention would you suggest? How would you know if your intervention worked?

You are a social worker working at a public policy center focused on homelessness. Your city is seeking a large federal grant to address the growing problem of homelessness in your area, and you have been hired as a consultant to work on the proposal. After conducting a needs assessment in collaboration with local social service agencies and interviewing people who are homeless, you meet with city council members to discuss potential programs. Local agencies want to spend the grant money to increase capacity at existing shelters and to create transitional housing by re-purposing an unused apartment complex. This way, individuals have a place to stay after the shelter where they can learn valuable independent living skills. On the other hand, you are aware that the clients would prefer to receive housing vouchers to rent apartments in the community. The clients also communicated that they fear shelters and transitional housing may impose on their daily lives by placing restrictions on guests and mandating quiet hours. When you ask the agencies about client feedback, they state that clients cannot be trusted to manage in their own apartments without the structure and supervision that is provided by agency support workers.

- What kind of program should your city choose to implement? Which program is most likely to be effective?

Assuming you've taken a social work course before, you will notice that the case studies cover different levels of analysis in the social ecosystem—micro, meso, and macro. At the micro-level, social workers examine the smallest levels of interaction, even interactions within “the self,” like in our first case study involving the misbehaving child. When social workers investigate groups and communities, such as our food desert scenario in case 2, they are operating at the meso-level. At the macro-level, social workers examine social structures and institutions. Research at the macro-level examines large-scale patterns, including culture and government policy, like the situation described in case 3. These domains interact with one another and it is common for a social work research project to address more than one level of analysis. Moreover, research that occurs on one level is likely to have implications at the other levels of analysis.

How do social workers know what to do?

Welcome to social work research. This chapter begins with three problems that social workers might face in practice and three questions about what a social worker should do next. If you haven’t already, spend a minute or two thinking about how you would respond to each case and jot down some notes. How would you respond to each of these cases?

I assume it is unlikely that you are an expert in the areas of children’s mental health, community responses to food deserts, and homelessness policy. Not to worry, neither am I. In fact, for many of you this textbook will likely come at an early point in your social work education, so it may seem unfair for me to ask you what the right answers are. And to disappoint you further, this course will not teach you the right answers to these questions, however it will teach you how to work through them and come to the right answer on your own. Social workers must learn how to examine the literature on a topic, come to a reasoned conclusion, and use that knowledge in their practice. Similarly, social workers engage in research to ensure that their interventions are helping, not harming, clients and that those interventions also contribute to social science and social justice.

Assuming that you may lack advanced knowledge of the topics addressed in the case studies, you likely made use of your intuition when imagining how you would react in each situation (Cheung, 2016). [1] Intuition is a way of knowing that is mostly unconscious, much like a gut feeling telling you what you should do. As you think about a problem such as those in the case studies, you notice certain details and ignore others. Using your past experiences, you apply knowledge that seems to be relevant and make predictions about what might be true.

In this way, intuition is based on direct experience. Many of us know things simply because we’ve experienced them directly. For example, you would know that electric fences can be pretty dangerous and painful if you touched one while standing in a puddle of water. Most of us can probably recall a time when we have learned something though experience. If you grew up in Minnesota, you would observe plenty of kids learning that your tongue really does stick to a metal pole in the winter. Similarly, you would learn that driving 20 miles above the speed limit on a major highway is a pretty easy way to earn a traffic ticket.

Intuition and direct experience are powerful forces. As a discipline, social work is unique because it values intuition, however it will take you quite a while to develop what social workers refer to as practice wisdom. Practice wisdom is the "learning by doing" that develops as one practices social work over time. Social workers also reflect on their practice, both independently and with colleagues, which sharpens their intuitions and opens their minds to other viewpoints. While your direct experience in social work may be limited at this point, feel confident that through reflective practice you will attain practice wisdom.

However, it’s important to note that intuitions are not always correct. Think back to the first case study. What might be your novice diagnosis for this child’s behavior? Does he have attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) because he is easily distracted and gets into trouble at school, or are those symptoms of autism spectrum disorder or an attachment disorder? Are the bruises on his legs an indicator of ADHD, or do they indicate possible physical abuse at home? Even if you arrived at an accurate assessment of the situation, you would still need to figure out what kind of intervention to use with the client. If he has a mental health issue, you might suggest therapy for the child, but what kind of therapy? Should we use cognitive-behavioral therapy, play therapy, art therapy, family therapy, or animal assisted therapy? Should we try a combination of therapy and medication prescribed by a psychiatrist?

We could guess which intervention would be best, but in practice that would be highly unethical. An incorrect guess could waste our time and the time of our client, or worse, it could actively harm a client. We need to ground our social work interventions with clients and systems with something more secure than our intuition and experience.

Cognitive biases

Although the human mind is a marvel of observation and data analysis, there are universal flaws in thinking that must be overcome. We all rely on mental shortcuts to help us make sense of a continuous stream of new information. All people, including you and I, must train their minds to be aware of predictable flaws in thinking, termed cognitive biases. Here is a link to the Wikipedia entry on cognitive biases. As you can see, it is quite long. We will review some of the most important ones here, but take a moment to browse around the link and get a sense of the extent to which cognitive biases are ingrained in human thinking.

The most important cognitive bias for social scientists to be aware of is confirmation bias. Confirmation bias involves observing and analyzing information in a way that confirms what you already think is true. No person is a blank slate. We arrive at each moment with a set of beliefs, experiences, and models of how the world works that we develop over time. Often, these are grounded in our own personal experiences. Confirmation bias assumes these intuitions are correct and ignores or manipulates new information in a way that avoids challenging our established beliefs.

Confirmation bias can be seen in many ways. Sometimes, people will only pay attention to the information that fits their preconceived ideas and ignore information that does not fit. This is called selective observation. Other times, people will make hasty conclusions about a broad pattern based on only a few observations. This is called overgeneralization. Let’s walk through an example and see how they each would function.

In our second case study, we are trying to figure out how to help people who receive SNAP (formerly Food Stamps) who live in a food desert. Let’s say that we have arrived at a solution and are now lobbying the city council to implement it. There are many people who have negative beliefs about people who are “on welfare.” These people believe individuals who receive social welfare benefits spend their money irresponsibly, are too lazy to get a job, and manipulate the system to maintain or increase their government payout. People expressing this belief may provide an example like Louis Cuff, who bought steak and lobster with his SNAP benefits and resold them for a profit.

City council members who hold these beliefs may ignore the truth about your client population. Your clients and other people experiencing poverty usually spend their money responsibly and they genuinely need help accessing fresh and healthy food. This would be an example of selective observation in which they are only paying attention to the cases that confirm their biased beliefs about people in poverty and ignoring evidence that challenges that perspective. Their beliefs are likely grounded in overgeneralization in which one example, like Mr. Cuff, is applied broadly to the population of people using social welfare programs. Social workers in this situation would have to hope that city council members are open to another perspective and can be swayed by evidence that challenges their beliefs. Otherwise, they will continue to rely on a biased view of people in poverty when they create policies.

But where do these beliefs and biases come from? Perhaps an authority figure told them that people in poverty are lazy and manipulative, and these beliefs may have been internalized without questioning. Naively relying on authority can take many forms. We might rely on our parents, friends, or religious leaders as authorities on a topic. We might consult someone who identifies as an expert in the field and simply follow what they say. We might hop aboard a “bandwagon” and adopt the fashionable ideas and theories of our peers and friends.

It is important to note that experts in the field should generally be trusted to provide accurate information on a topic, though their knowledge should be receptive to skeptical critique, as the state of knowledge will develop over time as more scholars study the topic. There are limits to skepticism, however. Disagreeing with experts about global warming, the shape of the earth, or the efficacy and safety of vaccines does not make one free of cognitive biases. On the contrary, it is likely that the person is falling victim to the Dunning-Kruger effect, in which unskilled people overestimate their ability to find the truth. As this comic illustrates, they are at the top of Mount Stupid. Only through rigorous, scientific inquiry can they progress down the back slope and hope to increase their depth of knowledge about a topic.

Scientific Inquiry

Cognitive biases are most often expressed when people are using informal observation. Until I asked at the beginning of this chapter, you may have had little reason to formally observe and make sense of information about children’s mental health, food deserts, or homelessness policy. Because you engaged in informal observation, it is more likely that you will express cognitive biases in your responses. Informal observation can be problematic because without any systemic process for observing or addressing the accuracy of our observations, we can never be sure of their accuracy. In order to minimize the effect of cognitive biases and come closer to truly understanding a topic, we must apply a systematic framework for understanding what we observe.

The opposite of informal observation is scientific inquiry, used interchangeably with the term research methods in this text. These terms refer to an organized, logical way of knowing that involves both theory and observation. Science can account for many of the limitations of cognitive biases, though not perfectly. Science ensures that observations are done rigorously by following a set of prescribed steps in which scientists clearly describe the methods they use to conduct observations and create theories about the social world. Theories are tested by observing the social world, and they can be shown to be false or incomplete. In short, scientists try to learn the truth. Social workers use scientific truths in their practice and conduct research to revise and extend our understanding of what is true in the social world. Social workers who ignore science and act based on biased or informal observation may actively harm clients.

Key Takeaways

- Social work research occurs on the micro-, meso-, and macro-level.

- Intuition is a powerful, though woefully incomplete, guide to action in social work.

- All human thought is subject to cognitive biases.

- Scientific inquiry accounts for cognitive biases by applying an organized, logical way of observing and theorizing about the world.

Glossary

Authority- learning by listening to what people in authority say is true

Cognitive biases- predictable flaws in thinking

Confirmation bias- observing and analyzing information in a way that confirms what you already think is true

Direct experience- learning through informal observation

Dunning-Kruger effect- when unskilled people overestimate their ability and knowledge (and experts underestimate their ability and knowledge)

Intuition- your "gut feeling" about what to do

Macro-level- examining social structures and institutions

Meso-level- examining interaction between groups

Micro-level- examining the smallest levels of interaction, usually individuals

Overgeneralization- using limited observations to make assumptions about broad patterns

Practice wisdom- “learning by doing” that guides social work intervention and increases over time

Research methods- an organized, logical way of knowing based on theory and observation

Image Attributions

Thinking woman by Free-Photos via Pixabay CC-0

Light bulb by MasterTux via Pixabay CC-0

Learning Objectives

- Define science

- Describe the difference between objective and subjective truth(s)

- Describe the roles of ontology and epistemology in scientific inquiry

Science and social work

Science is a particular way of knowing that attempts to systematically collect and categorize facts or truths. A key word here is "systematically," because it is important to understand that conducting science is a deliberate process. Scientists gather information about facts in a way that is organized and intentional, usually following a set of predetermined steps. More specifically, social work is informed by social science, the science of humanity, social interactions, and social structures. In sum, social work research uses organized and intentional procedures to uncover facts or truths about the social world and it also relies on social scientific research to promote individual and social change.

Philosophy of social science

This approach to finding truth probably sounds similar to something you heard in your middle school science classes. When you learned about the gravitational force or the mitochondria of a cell, you were learning about the theories and observations that make up our understanding of the physical world. These theories rely on an ontology, or a set of assumptions about what is real. We assume that gravity is real and that the mitochondria of a cell are real. With a powerful microscope, mitochondria are easy to spot and observe, and we can theorize about their function in a cell. The gravitational force is invisible, but clearly apparent from observable facts, like watching an apple fall. The theories about gravity have changed over the years, and those improvements in theory were made when existing theories fell short in explaining observations.

If we weren’t able to perceive mitochondria or gravity, they would still be there, doing their thing because they exist independent of our observation of them. This is a philosophical idea called realism, and it simply means that the concepts we talk about in science really and truly exist. Ontology in physics and biology is focused on objective truth. You may have heard the term “being objective” before: it involves observing and thinking with an open mind and pushing aside anything that might bias your perspective. Objectivity also involves finding what is true for everyone, not just what is true for one person. Gravity is certainly true for everyone, everywhere, but let’s consider a social work example. It is objectively true that children who are subjected to severely traumatic experiences will experience negative mental health effects afterwards. A diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is considered objective because it refers to a real mental health issue that exists independent of the social worker’s observations, and it presents similarly in all clients who experience the disorder.

Objective, ontological perspective implies that observations are true for everyone, regardless of whether we are there to observe them or not observe them. Epistemology, or our assumptions about how we come to know what is real and true, helps us to realize these objective truths. The most relevant epistemological question in the social sciences is whether truth is better accessed using numbers or words. Generally, scientists approaching research with an objective ontology and epistemology will use quantitative methods to arrive at scientific truth. Quantitative methods examine numerical data to precisely describe and predict elements of the social world. This is due to the epistemological assumption that mathematics can represent the phenomena and relationships we observe in the social world.

Mathematical relationships are uniquely useful because allow us to make comparisons across individuals as well as time and space. For example, let’s look at measures of poverty. While people can have different definitions of poverty, an objective measurement such as an annual income less than $25,100 for a family of four is insightful because (1) it provides a precise measurement, (2) it can be compared to incomes from all other people in any society from any time period, and (3) it refers to real quantities of money that exist in the world. In this book, we will review survey and experimental methods, which are the most common designs that use quantitative methods to answer research questions.

It may surprise you to learn that objective facts, like income or mental health diagnoses, are not the only facts that are present in the social sciences. Indeed, social science is not only concerned with objective truths, but it is also concerned with subjective truth. Subjective truths are unique to individuals, groups, and contexts. Unlike objective truths, subjective truths will vary based on who you are observing and the context you are observing them in. The beliefs, opinions, and preferences of people are actually truths that social scientists measure and describe. Additionally, subjective truths do not exist independent of human observation because they are the product of the human mind. We negotiate what is true in the social world through language, arriving at a consensus and engaging in debate.

Epistemologically, a scientist seeking subjective truth assumes that truth lies in what people say, in their words. A scientist uses qualitative methods to analyze words or other media to understand their meaning. Humans are social creatures, and we give meaning to our thoughts and feelings through language. Linguistic communication is unique. We share ideas with each other at a remarkable rate. In so doing, ideas come into and out of existence in a spontaneous and emergent fashion. Words are given a meaning by their creator., but anyone who receives that communication can absorb, amplify, and even change its original intent. Because social science studies human interaction, subjectivists argue that language is the best way to understand the world.

This epistemology is based on some interesting ontological assumptions. What happens when someone incorrectly interprets a situation? While their interpretation may be wrong, it is certainly true to them that they are right. Furthermore, they act on the assumption that they are right. In this sense, even incorrect interpretations are truths, even though they are only true to one person. This leads us to question whether the social concepts we think about really exist. They might only exist in our heads, unlike concepts from the natural sciences which exist independent of our thoughts. For example, if everyone ceased to believe in gravity, we wouldn’t all float away. It has an existence independent of human thought.

Let's think through an example. In the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) classification of mental health disorders, there is a list of culture-bound syndromes which only appear in certain cultures. For example, susto describes a unique cluster of symptoms experienced by people in Latin American cultures after a traumatic event that focus on the body. Indeed, many of these syndromes do not fit within a Western conceptualization of mental health because Western culture differentiates less between the mind and body. To a Western scientist, susto may seem less real than PTSD. To someone from Latin America, their symptoms may not fit neatly into the PTSD framework developed within Western society. This conflict raises the question: do either susto or PTSD really exist at all? If your answer is “no,” then you are adopting the ontology of anti-realism, which is the belief that social concepts do not have an existence apart from human thought. Unlike realists who seek a single, universal truth, the anti-realist sees a collection of truths that are created and shared within a social and cultural environment.

Let’s consider another example: manels or all-male panel discussions at conferences and conventions. Check out this National Public Radio article for some hilarious examples, ironically including panels about diversity and gender representation. Manels are a problem in academic gatherings, Comic-Cons, and other large group events. Over the last few decades, feminist critique has helped us to realize that manels are a holdover of sexist stereotypes and gender-based privilege that perpetuate the idea that men are the experts who deserve to be listened to by other, less important and knowledgeable people. However, let’s look at an example. We will take the perspective of a few different participants at a hypothetical conference and examine their individual, subjective truths.

Imagine that the conference schedule is announced. Of the ten panel discussions that are announced, only two panels contain women. Mei, an expert on the neurobiology of child abuse, thinks that this is unfair, as she was excluded from a panel on her specialty. Marco, an event organizer, feels that the results could not be sexist because the organizers simply invited those who were most qualified to speak, regardless of gender. Dionne, a professor who specializes in queer theory and indigenous social work, agrees with Mei that manels are sexist. However, she also feels that the focus on gender excludes and overlooks the problems with race, disability, sexual and gender identity, and social class among the conference panel members. Given these differing interpretations, how can we come to know what is true about this situation?

Honestly, there are many truths present in this example. Clearly, Pamela’s truth is that manels are sexist. Marco’s truth is that they are not necessarily sexist, as long as they were chosen in a sex-blind manner. While none of these statements are objectively true, they are subjectively true to the individual who thought of them. Subjective truth consists of the the different meanings, understandings, and interpretations created by people and communicated throughout society. The communication of ideas is important, as it is how people come to a consensus on how to interpret a situation and negotiate the meaning of events, and it informs how people act. Thus, as feminist critiques of society become more accepted, people will behave in less sexist ways. From a subjective perspective, there is no magical number of female panelists that conferences must reach to be sufficiently non-sexist. Instead, we should use language to investigate how people interpret the gender issues at the event and analyze them within a historical and cultural context. How do we find truth when everyone has their own unique interpretation? We must find patterns.

Science means finding patterns in data

Regardless of whether you are seeking objective or subjective truths, research and scientific inquiry aim to find and explain patterns. Most of the time, a pattern will not explain every single person’s experience, and this is a fact about social science that is both fascinating and frustrating. Even individuals who do not know each other and do not coordinate in any deliberate way can create patterns that persist over time. Those new to social science may find these patterns frustrating because they may believe that the patterns that describe their gender, age, or some other facet of their lives don’t really represent their experience. It’s true. A pattern can exist among your cohort without your individual participation in it. There is diversity within diversity.

Let’s consider some specific examples. One area that social workers commonly investigate is the impact of a person’s social class background on their experiences and lot in life. You probably wouldn’t be surprised to learn that a person’s social class background has an impact on their educational attainment and achievement. In fact, one group of researchers [2] in the early 1990s found that the percentage of children who did not receive any postsecondary schooling was four times greater among those in the lowest quartile (25%) income bracket than those in the upper quartile of income earners (i.e., children from high- income families were far more likely than low-income children to go on to college). Another recent study found that having more liquid wealth that can be easily converted into cash actually seems to predict children’s math and reading achievement (Elliott, Jung, Kim, & Chowa, 2010). [3]

These findings—that wealth and income shape a child’s educational experiences—are probably not that shocking to any of us. Yet, some of us may know someone who may be an exception to the rule. Sometimes the patterns that social scientists observe fit our commonly held beliefs about the way the world works. When this happens, we don’t tend to take issue with the fact that patterns don’t necessarily represent all people’s experiences. But what happens when the patterns disrupt our assumptions?

For example, did you know that teachers are far more likely to encourage boys to think critically in school by asking them to expand on answers they give in class and by commenting on boys’ remarks and observations? When girls speak up in class, teachers are more likely to simply nod and move on. The pattern of teachers engaging in more complex interactions with boys means that boys and girls do not receive the same educational experience in school (Sadker & Sadker, 1994). [4] You and your classmates, of all genders, may find this news upsetting.

People who object to these findings tend to cite evidence from their own personal experience, refuting that the pattern actually exists. However, the problem with this response is that objecting to a social pattern on the grounds that it doesn’t match one’s individual experience misses the point about patterns. Patterns don’t perfectly predict what will happen to an individual person, yet they are a reasonable guide. When patterns are systematically observed, they can help guide social work thought and action.

A final note on qualitative and quantitative methods

There is no one superior way to find patterns that help us understand the world. As we will learn about in Chapter 6, there are multiple philosophical, theoretical, and methodological ways to approach uncovering scientific truths. Qualitative methods aim to provide an in-depth understanding of a relatively small number of cases. Quantitative methods offer less depth on each case but can say more about broad patterns in society because they typically focus on a much larger number of cases. A researcher should approach the process of scientific inquiry by formulating a clear research question and conducting research using the methodological tools best suited to that question.

Believe it or not, there are still significant methodological battles being waged in the academic literature on objective vs. subjective social science. Usually, quantitative methods are viewed as “more scientific” and qualitative methods are viewed as “less scientific.” Part of this battle is historical. As the social sciences developed, they were compared with the natural sciences, especially physics, which rely on mathematics and statistics to find truth. It is a hotly debated topic whether social science should adopt the philosophical assumptions of the natural sciences—with its emphasis on prediction, mathematics, and objectivity—or use a different set of tools—understanding, language, and subjectivity—to find scientific truth.

You are fortunate to be in a profession that values multiple scientific ways of knowing. The qualitative/quantitative debate is fueled by researchers who may prefer one approach over another, either because their own research questions are better suited to one particular approach or because they happened to have been trained in one specific method. In this textbook, we’ll operate from the perspective that qualitative and quantitative methods are complementary rather than competing. While these two methodological approaches certainly differ, the main point is that they simply have different goals, strengths, and weaknesses. A social work researcher should choose the methods that best match with the question they are asking.

Key Takeaways

- Social work is informed by science.

- Social science is concerned with both objective and subjective knowledge.

- Social science research aims to understand patterns in the social world.

- Social scientists use both qualitative and quantitative methods. While different, these methods are often complementary.

Glossary

Epistemology- a set of assumptions about how we come to know what is real and true

Objective truth- a single truth, observed without bias, that is universally applicable

Ontology- a set of assumptions about what is real

Qualitative methods- examine words or other media to understand their meaning

Quantitative methods- examine numerical data to precisely describe and predict elements of the social world

Science- a particular way of knowing that attempts to systematically collect and categorize facts or truth

Subjective truth- one truth among many, bound within a social and cultural context

Image Attributions

Science and Technology by Petr Kratochvil CC-0

Abstract art blur bright by Pixabay CC-0

Learning Objectives

- Describe and discuss four important reasons why students should care about social scientific research methods

- Identify how social workers use research as part of evidence-based practice

At this point, you may be wondering about the relevance of research methods to your life. Whether or not you choose to become a social worker, you should care about research methods for two basic reasons: (1) research methods are regularly applied to solve social problems and issues that shape how our society is organized, thus you have to live with the results of research methods every day of your life, and (2) understanding research methods will help you evaluate the effectiveness of social work interventions, which is an important skill for future employment.

Consuming research and living with its results

Another New Yorker cartoon depicts two men chatting with each other at a bar. One is saying to the other, “Are you just pissing and moaning, or can you verify what you’re saying with data?” (https://condenaststore.com/featured/are-you-just-pissing-and-moaning-edward-koren.html). Think about yourself: Would you rather be a complainer or someone who can verify what they say? Understanding research methods and how they work can help position you to actually do more than just complain. Further, whether you know it or not, research probably has some impact on your life each and every day. Many of our laws, social policies, and court proceedings are grounded in some degree of empirical research and evidence (Jenkins & Kroll-Smith, 1996). [5] That’s not to say that all laws and social policies are good or make sense. However, you can’t have an informed opinion about any of them without understanding where they come from, how they were formed, and what their evidence base is. All social workers, from micro to macro, need to understand the root causes and policy solutions to social problems that their clients are experiencing.

A recent lawsuit against Walmart provides an example of social science research in action. A sociologist named Professor William Bielby was enlisted by plaintiffs in the suit to conduct an analysis of Walmart’s personnel policies in order to support their claim that Walmart engages in gender discriminatory practices. Bielby’s analysis shows that Walmart’s compensation and promotion decisions may indeed have been vulnerable to gender bias. In June 2011, the United States Supreme Court decided against allowing the case to proceed as a class-action lawsuit (Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. v. Dukes, 2011). [6] While a class-action suit was not pursued in this case, consider the impact that such a suit against one of our nation’s largest employers could have on companies and their employees around the country and perhaps even on your individual experience as a consumer. [7]

In addition to having to live with laws and policies that have been crafted based on social science research, you are also a consumer of all kinds of research. A strong understanding of research methods can help you be a more informed consumer. Have you ever noticed the magazine headlines that peer out at you while you are waiting in line to pay for your groceries? They are geared toward piquing your interest and making you believe that you will learn a great deal if you follow the advice in a particular article. However, since you would have no way of knowing whether the magazine’s editors had gathered their data from a representative sample of people like you and your friends, you would have no reason to believe that the advice would be worthwhile. By having some understanding of research methods, you can avoid wasting your money on magazines and avoid wasting your time on inappropriate advice.

If you were to pick up any magazine or newspaper or tune into any news broadcast, you are likely to hear about some new and exciting research results. A strong understanding of research methods will help you to read past the type of vague headlines and ask clarifying questions about what you see and hear in the media. In other words, research methods can help you to become a more responsible consumer of public and popular information. Who wouldn’t want to be more responsibly informed?

Evidence-based practice

At some point in your schooling, I am sure that you have felt as though a class was not relevant and found yourself wondering when you’ll ever need the information in “real life.” You may not believe me, but the research methods from this text will be used often in your careers. Social work supervisors and administrators at agency-based settings will likely have to demonstrate that their agency’s programs are effective at achieving their goals. Most private and public grants will require evidence of effectiveness for your agency to receive funding and to keep the programs running. Social workers at community-based organizations commonly use research methods to target their interventions to the needs of their service area. Clinical social workers must also make sure that the interventions they use in practice are effective and not harmful to clients. In addition, social workers may want to track client progress on goals, help clients gather data about their clinical issues, or use data to advocate for change. As a whole, all social workers in all practice situations must remain current on the scientific literature to ensure competent and ethical practice.

In all of these cases, a social worker needs to be able to understand and evaluate scientific information. Evidence-based practice (EBP) for social workers involves making decisions on how to help clients based on the best available evidence. A social worker must examine the current literature and understand both the theory and evidence relevant to the practice situation. According to Rubin and Babbie (2017), [8] EBP also involves understanding client characteristics, using practice wisdom and existing resources, and adapting to environmental context. It is not simply “doing what the literature says,” but rather a process by which practitioners examine the literature, client, self, and context to inform interventions with clients and systems. As we discussed in Section 1.2, the patterns discovered by scientific research are not perfectly applicable to all situations. Instead, we rely on the critical thinking of social workers to apply scientific knowledge to real-world situations.

Let’s consider an example of a social work administrator at a children’s mental health agency. The agency uses a private grant to fund a program that provides low-income children with bicycles, teaches the children how to repair and care for their bicycles, and leads group bicycle outings after school. Physical activity has been shown to improve mental health outcomes in scientific studies, but is this social worker’s program improving mental health in their clients? Ethically, the social worker should make sure that the program is achieving its goals. If the program is not beneficial, the resources should be spent on more effective programs. Practically, the social worker will also need to demonstrate to the agency’s donors that bicycling truly helps children deal with their mental health concerns.

The example above demonstrates the need for social workers to engage in evaluation research, or research that evaluates the outcomes of a policy or program. She will choose from many acceptable ways to investigate program effectiveness, and those choices are based on the principles of scientific inquiry you will learn in this textbook. As the example above mentions, evaluation research is embedded into the funding of nonprofit, human service agencies. Government and private grants need to make sure their money is being spent wisely. If your program does not work, then the funds will be allocated to a program that has been proven effective or a new program that may be effective. Just because a program has the right goal doesn’t mean it will actually accomplish that goal. Grant reporting is an important part of agency-based social work practice. Agencies, in a very important sense, help us discover what approaches actually help clients.

In addition to engaging in evaluation research to satisfy the requirements of a grant, your agency may also engage in evaluation research to validate a new approach to treatment. Innovation in social work is incredibly important. Sam Tsemberis relates an “aha” moment from his practice in this Ted talk on homelessness (https://youtu.be/HsFHV-McdPo). As a faculty member at the New York University School of Medicine, he noticed a problem with people cycling in and out of the local psychiatric hospital wards. Clients would arrive in psychiatric crisis, become stable with the help of medical supervision, and end up back in the psychiatric crisis ward shortly after discharge. When he asked the clients what their issues were, they said they were unable to participate in homelessness programs because they were not always compliant with medication for their mental health diagnosis and they continued to use drugs and alcohol. Collaboratively, the problem facing these clients was defined as a homelessness service system that was unable to meet clients where they were. Clients who were unwilling to remain completely abstinent from drugs and alcohol or who did not want to take psychiatric medications were simply cycling in and out of psychiatric crisis, moving from the hospital to the street and back to the hospital.

The solution that Sam Tsemberis implemented and popularized was called Housing First. It is an approach to homelessness prevention that starts by, you guessed it, providing people with housing first. Like Tanya Tull’s approach to address child and family homelessness, Tsemberis created a model to address chronic homelessness in people with co-occurring disorders (substance abuse and mental illness). The Housing First model holds that housing is a human right, one that should not be denied based on substance use or mental health diagnosis. Clients are given housing as soon as possible. The Housing First agency provides wraparound treatment from an interdisciplinary team, including social workers, nurses, psychiatrists, and former clients who are in recovery. Over the past few decades, this program has gone from one program in New York City to the program of choice for federal, state, and local governments seeking to address homelessness in their communities.

The main idea behind Housing First is that once clients have an apartment of their own, they are better able to engage in mental health and substance abuse treatment. While this approach may seem logical to you, it is backwards from the traditional homelessness treatment model. The traditional approach began with the client stopping drug and alcohol use and taking prescribed medication. Only after clients achieved these goals were they offered group housing. If the client remained sober and medication compliant, they could then graduate towards less restrictive individual housing.

Evaluation research helps practitioners establish that their innovation is better than the alternatives and should be implemented more broadly. By comparing clients who were served through Housing First and traditional treatment, Tsemberis could establish that Housing First was more effective at keeping people housed and progressing on mental health and substance abuse goals. Starting first with smaller studies and graduating to much larger ones, Housing First built a reputation as an effective approach to addressing homelessness. When President Bush created the Collaborative Initiative to Help End Chronic Homelessness in 2003, Housing First was used in many of the interventions and its effectiveness was demonstrated on a national scale. In 2007, it was acknowledged as an evidence-based practice in the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s (SAMHSA) National Registry of Evidence-Based Programs and Policies (NREPP). [9]

I suggest browsing around the NREPP website (https://nrepp.samhsa.gov/landing.aspx) and looking for interventions on topics that interest you. Other sources of evidence-based practices include the Cochrane Reviews digital library (http://www.cochranelibrary.com/) and Campbell Collaboration (https://campbellcollaboration.org/). In the next few chapters, we will talk more about how to find literature about interventions in social work. The use of systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and randomized controlled trials are particularly important in this regard.

So why share the story of Housing First? Well, I want you think about what you hope to contribute to our knowledge on social work practice. What is your bright idea and how can it change the world? Practitioners innovate all the time, often incorporating those innovations into their agency’s approach and mission. Through the use of research methods, agency-based social workers can demonstrate to policymakers and other social workers that their innovations should be more widely used. Without this wellspring of new ideas, social services would not be able to adapt to the changing needs of clients. Social workers in agency-based practice may also participate in research projects happening at their agency. Partnerships between schools of social work and agencies are a common way of testing and implementing innovations in social work. Clinicians receive specialized training, clients receive additional services, agencies gain prestige, and researchers can study how an intervention works in the real world.

While you may not become a scientist in the sense of wearing a lab coat and using a microscope, social workers must understand science in order to engage in ethical practice. In this section, we reviewed many ways in which research is a part of social work practice, including:

- Determining the best intervention for a client or system

- Ensuring existing services are accomplishing their goals

- Satisfying requirements to receive funding from private agencies and government grants

- Testing a new idea and demonstrating that it should be more widely implemented

Key Takeaways

- Whether we know it or not, our everyday lives are shaped by social scientific research.

- Understanding research methods is important for competent and ethical social work practice.

- Understanding social science and research methods can help us become more astute and more responsible consumers of information.

- Knowledge about social scientific research methods is important for ethical practice, as it ensures interventions are based on evidence.

Glossary

Evaluation research- research that evaluates the outcomes of a policy or program

Evidence-based practice- making decisions on how to help clients based on the best available evidence

Image Attributions

A peer counselor with mother by US Department of Agriculture CC-BY-2.0

Homeless man in New York 2008 by JMSuarez CC-BY-2.0

Learning Objectives

- Describe common barriers to engaging with social work research

- Identify alternative ways of thinking about research methods

I’ve been teaching research methods for six years and have found many students struggle to see the connection between research and social work practice. Most students enjoy a social work theory class because they can better understand the world around them. Students also like social work practice courses because they are taught how to conduct clinical work with clients, which is what most social work students want to do. On the other hand, it is less common for me to have a student that is interested in becoming a social work researcher. For this reason, I want to end this chapter on a more personal note. Most student barriers to research come from the following beliefs:

Research is useless!

Students are saying something important when they tell me that research methods is not a useful class to them. As a scholar (or student), your most valuable asset is your time. You give your time to the subjects you consider important to you and your future practice. Because most social workers don’t become researchers or practitioner-researchers, students feel like a research methods class is a waste of time.

Social workers play an important role in creating new knowledge about social services, as presented in our previous discussion of evidence-based practice and the use of research methods. On a more immediate level, research methods will also help you become a stronger social work student. The next few chapters of this textbook will review how to search for literature on a topic and write a literature review. These skills are relevant in every classroom during your academic career. The rest of the textbook will help you understand the mechanics of research methods so you can better understand the content of those pesky journal articles your professors force you to cite in your papers.

Research is too hard!

Research methods involves a lot of terminology that is entirely new to social workers. Other domains of social work are easier to apply your intuition towards. In a social work practice course, you may feel more at ease because you understand how to be an empathetic person, and your experiences in life can help guide you through a practice situation or even theoretical or conceptual question. Research may seem like a totally new area in which you have no previous experience. It can seem like a lot to learn. In addition to the normal memorization and application of terms, research methods also has wrong answers. There are certain combinations of methods that just don’t work together.

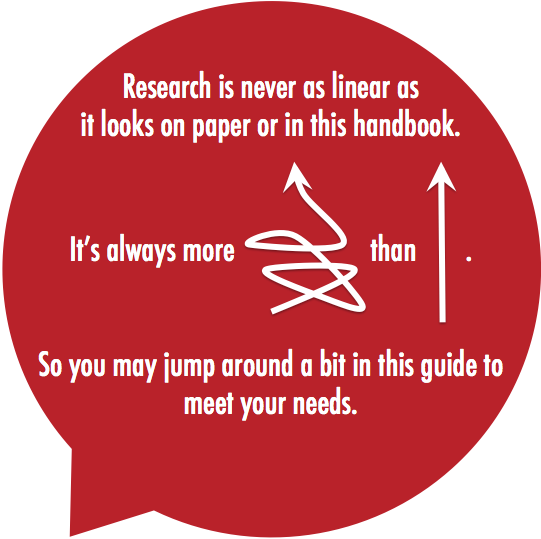

The fear is entirely understandable. Research is not straightforward. As Figure 1.1 shows, it is a process that is non-linear, involving multiple revisions, wrong turns, and dead ends before you figure out the best question and research approach. You may have to go back to chapters after having read them or even peek ahead at chapters your class hasn’t covered yet.

Moreover, research is something you learn by doing…and stumbling a few times. It’s an iterative process, which means that you must try many times before you get it right. There isn’t a shortcut for learning research, but hopefully your research methods class is one in which your research project is broken down into smaller parts and you get consistent feedback throughout the process. No one just knows research. It’s something you pick up by doing it, reflecting on the experiences and results, redoing your work, and revising it in consultation with your professor.

Research is boring!

We’ve already discussed the arcane research terminology, so I won’t go into it again here, but research methods is regarded as a boring topic by many students. Practice knowledge and even theory are fun to learn because they are easy to apply and give you insight into the world around you. Research just seems like its own weird, remote thing.

I completely understand where this perspective comes from and hope there are a few things you will take away from this course that aren’t boring to you. In the first section of this textbook, you will learn how to take any topic and learn what is known about it. It may seem trivial, but it is actually a superpower. Your social work education will present some generalist material, which is applicable to nearly all social work practice situations, and some applied material, which is applicable to specific social work practice situations. However, there is no education that will provide you with everything you need to know, and there is certainly no education that can tell you what will be discovered over the next few decades of your practice. Our work on literature reviews in the next few chapters will help you to become a strong social work student and practitioner. Following that, our exploration of research methods will help you further understand how the theories, practice models, and techniques you learn in your other classes are created and tested scientifically.

Get out of your own way

Together, the beliefs of “research is useless, boring, and hard” can create a self-fulfilling prophecy for students. If you believe that research is boring, then you won’t find it interesting. If you believe that research is hard, then you will struggle more with assignments. If you believe that research is useless, then you won’t see its utility. While I certainly acknowledge that students aren’t going to love research as much as I do (it’s a career for me, so I like it a lot!), I suggest reframing how you think about research using these touchstones:

- All social workers rely on social science research to engage in competent practice.

- No one already knows research. It’s something I’ll learn through practice, and it’s challenging for everyone.

- Research is relevant to me because it allows me to figure out what is known about any topic I want to study.

- If the topic I choose to study is important to me, I will be more interested in research.

Structure of this textbook

While you may not have chosen this course, you can increase the likelihood of academic gain by reframing your approach to it. To that end, here is the structure of this book:

In Chapters 2-4, we’ll review how to begin a research project. This involves searching for relevant literature, specifically from academic journals, and synthesizing what they say about your topic into a literature review.

In Chapters 5-9, you’ll learn about how research informs and tests theory. We’ll discuss how to conduct research in an ethical manner, create research questions, and measure concepts in the social world.

Chapters 10-14 will describe how to conduct research, whether it’s a quantitative survey or experiment, or a qualitative interview or focus group. We’ll also review how to analyze data that someone else has already collected.

Finally, Chapters 15 and 16 will review the types of research most commonly used in social work practice, including evaluation research and action research, and how to report the results of your research to various audiences.

Key Takeaways

- Anxiety about research methods is a common experience for students.

- Research methods will help you become a better scholar and practitioner.