20 Reliability and Validity of Measurement

Learning Objectives

- Define reliability, including the different types and how they are assessed.

- Define validity, including the different types and how they are assessed.

- Describe the kinds of evidence that would be relevant to assessing the reliability and validity of a particular measure.

Again, measurement involves assigning scores to individuals so that they represent some characteristic of the individuals. But how do researchers know that the scores actually represent the characteristic, especially when it is a construct like intelligence, self-esteem, depression, or working memory capacity? The answer is that they conduct research using the measure to confirm that the scores make sense based on their understanding of the construct being measured. This is an extremely important point. Psychologists do not simply assume that their measures work. Instead, they collect data to demonstrate that they work. If their research does not demonstrate that a measure works, they stop using it.

As an informal example, imagine that you have been dieting for a month. Your clothes seem to be fitting more loosely, and several friends have asked if you have lost weight. If at this point your bathroom scale indicated that you had lost 10 pounds, this would make sense and you would continue to use the scale. But if it indicated that you had gained 10 pounds, you would rightly conclude that it was broken and either fix it or get rid of it. In evaluating a measurement method, psychologists consider two general dimensions: reliability and validity.

Reliability

Reliability refers to the consistency of a measure. Psychologists consider three types of consistency: over time (test-retest reliability), across items (internal consistency), and across different researchers (inter-rater reliability).

Test-Retest Reliability

When researchers measure a construct that they assume to be consistent across time, then the scores they obtain should also be consistent across time. Test-retest reliability is the extent to which this is actually the case. For example, intelligence is generally thought to be consistent across time. A person who is highly intelligent today will be highly intelligent next week. This means that any good measure of intelligence should produce roughly the same scores for this individual next week as it does today. Clearly, a measure that produces highly inconsistent scores over time cannot be a very good measure of a construct that is supposed to be consistent.

Assessing test-retest reliability requires using the measure on a group of people at one time, using it again on the same group of people at a later time, and then looking at the test-retest correlation between the two sets of scores. This is typically done by graphing the data in a scatterplot and computing the correlation coefficient. Figure 4.2 shows the correlation between two sets of scores of several university students on the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale, administered two times, a week apart. The correlation coefficient for these data is +.95. In general, a test-retest correlation of +.80 or greater is considered to indicate good reliability.

Again, high test-retest correlations make sense when the construct being measured is assumed to be consistent over time, which is the case for intelligence, self-esteem, and the Big Five personality dimensions. But other constructs are not assumed to be stable over time. The very nature of mood, for example, is that it changes. So a measure of mood that produced a low test-retest correlation over a period of a month would not be a cause for concern.

Internal Consistency

Another kind of reliability is internal consistency, which is the consistency of people’s responses across the items on a multiple-item measure. In general, all the items on such measures are supposed to reflect the same underlying construct, so people’s scores on those items should be correlated with each other. On the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale, people who agree that they are a person of worth should tend to agree that they have a number of good qualities. If people’s responses to the different items are not correlated with each other, then it would no longer make sense to claim that they are all measuring the same underlying construct. This is as true for behavioral and physiological measures as for self-report measures. For example, people might make a series of bets in a simulated game of roulette as a measure of their level of risk seeking. This measure would be internally consistent to the extent that individual participants’ bets were consistently high or low across trials.

Like test-retest reliability, internal consistency can only be assessed by collecting and analyzing data. One approach is to look at a split-half correlation. This involves splitting the items into two sets, such as the first and second halves of the items or the even- and odd-numbered items. Then a score is computed for each set of items, and the relationship between the two sets of scores is examined. For example, Figure 4.3 shows the split-half correlation between several university students’ scores on the even-numbered items and their scores on the odd-numbered items of the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale. The correlation coefficient for these data is +.88. A split-half correlation of +.80 or greater is generally considered good internal consistency.

Perhaps the most common measure of internal consistency used by researchers in psychology is a statistic called Cronbach’s α (the Greek letter alpha). Conceptually, α is the mean of all possible split-half correlations for a set of items. For example, there are 252 ways to split a set of 10 items into two sets of five. Cronbach’s α would be the mean of the 252 split-half correlations. Note that this is not how α is actually computed, but it is a correct way of interpreting the meaning of this statistic. Again, a value of +.80 or greater is generally taken to indicate good internal consistency.

Interrater Reliability

Many behavioral measures involve significant judgment on the part of an observer or a rater. Inter-rater reliability is the extent to which different observers are consistent in their judgments. For example, if you were interested in measuring university students’ social skills, you could make video recordings of them as they interacted with another student whom they are meeting for the first time. Then you could have two or more observers watch the videos and rate each student’s level of social skills. To the extent that each participant does, in fact, have some level of social skills that can be detected by an attentive observer, different observers’ ratings should be highly correlated with each other. Inter-rater reliability would also have been measured in Bandura’s Bobo doll study. In this case, the observers’ ratings of how many acts of aggression a particular child committed while playing with the Bobo doll should have been highly positively correlated. Interrater reliability is often assessed using Cronbach’s α when the judgments are quantitative or an analogous statistic called Cohen’s κ (the Greek letter kappa) when they are categorical.

Validity

Validity is the extent to which the scores from a measure represent the variable they are intended to. But how do researchers make this judgment? We have already considered one factor that they take into account—reliability. When a measure has good test-retest reliability and internal consistency, researchers should be more confident that the scores represent what they are supposed to. There has to be more to it, however, because a measure can be extremely reliable but have no validity whatsoever. As an absurd example, imagine someone who believes that people’s index finger length reflects their self-esteem and therefore tries to measure self-esteem by holding a ruler up to people’s index fingers. Although this measure would have extremely good test-retest reliability, it would have absolutely no validity. The fact that one person’s index finger is a centimeter longer than another’s would indicate nothing about which one had higher self-esteem.

Discussions of validity usually divide it into several distinct “types.” But a good way to interpret these types is that they are other kinds of evidence—in addition to reliability—that should be taken into account when judging the validity of a measure. Here we consider three basic kinds: face validity, content validity, and criterion validity.

Face Validity

Face validity is the extent to which a measurement method appears “on its face” to measure the construct of interest. Most people would expect a self-esteem questionnaire to include items about whether they see themselves as a person of worth and whether they think they have good qualities. So a questionnaire that included these kinds of items would have good face validity. The finger-length method of measuring self-esteem, on the other hand, seems to have nothing to do with self-esteem and therefore has poor face validity. Although face validity can be assessed quantitatively—for example, by having a large sample of people rate a measure in terms of whether it appears to measure what it is intended to—it is usually assessed informally.

Face validity is at best a very weak kind of evidence that a measurement method is measuring what it is supposed to. One reason is that it is based on people’s intuitions about human behavior, which are frequently wrong. It is also the case that many established measures in psychology work quite well despite lacking face validity. The Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-2 (MMPI-2) measures many personality characteristics and disorders by having people decide whether each of over 567 different statements applies to them—where many of the statements do not have any obvious relationship to the construct that they measure. For example, the items “I enjoy detective or mystery stories” and “The sight of blood doesn’t frighten me or make me sick” both measure the suppression of aggression. In this case, it is not the participants’ literal answers to these questions that are of interest, but rather whether the pattern of the participants’ responses to a series of questions matches those of individuals who tend to suppress their aggression.

Content Validity

Content validity is the extent to which a measure “covers” the construct of interest. For example, if a researcher conceptually defines test anxiety as involving both sympathetic nervous system activation (leading to nervous feelings) and negative thoughts, then his measure of test anxiety should include items about both nervous feelings and negative thoughts. Or consider that attitudes are usually defined as involving thoughts, feelings, and actions toward something. By this conceptual definition, a person has a positive attitude toward exercise to the extent that they think positive thoughts about exercising, feels good about exercising, and actually exercises. So to have good content validity, a measure of people’s attitudes toward exercise would have to reflect all three of these aspects. Like face validity, content validity is not usually assessed quantitatively. Instead, it is assessed by carefully checking the measurement method against the conceptual definition of the construct.

Criterion Validity

Criterion validity is the extent to which people’s scores on a measure are correlated with other variables (known as criteria) that one would expect them to be correlated with. For example, people’s scores on a new measure of test anxiety should be negatively correlated with their performance on an important school exam. If it were found that people’s scores were in fact negatively correlated with their exam performance, then this would be a piece of evidence that these scores really represent people’s test anxiety. But if it were found that people scored equally well on the exam regardless of their test anxiety scores, then this would cast doubt on the validity of the measure.

A criterion can be any variable that one has reason to think should be correlated with the construct being measured, and there will usually be many of them. For example, one would expect test anxiety scores to be negatively correlated with exam performance and course grades and positively correlated with general anxiety and with blood pressure during an exam. Or imagine that a researcher develops a new measure of physical risk taking. People’s scores on this measure should be correlated with their participation in “extreme” activities such as snowboarding and rock climbing, the number of speeding tickets they have received, and even the number of broken bones they have had over the years. When the criterion is measured at the same time as the construct, criterion validity is referred to as concurrent validity; however, when the criterion is measured at some point in the future (after the construct has been measured), it is referred to as predictive validity (because scores on the measure have “predicted” a future outcome).

Criteria can also include other measures of the same construct. For example, one would expect new measures of test anxiety or physical risk taking to be positively correlated with existing established measures of the same constructs. This is known as convergent validity.

Assessing convergent validity requires collecting data using the measure. Researchers John Cacioppo and Richard Petty did this when they created their self-report Need for Cognition Scale to measure how much people value and engage in thinking (Cacioppo & Petty, 1982)[1]. In a series of studies, they showed that people’s scores were positively correlated with their scores on a standardized academic achievement test, and that their scores were negatively correlated with their scores on a measure of dogmatism (which represents a tendency toward obedience). In the years since it was created, the Need for Cognition Scale has been used in literally hundreds of studies and has been shown to be correlated with a wide variety of other variables, including the effectiveness of an advertisement, interest in politics, and juror decisions (Petty, Briñol, Loersch, & McCaslin, 2009)[2].

Discriminant Validity

Discriminant validity, on the other hand, is the extent to which scores on a measure are not correlated with measures of variables that are conceptually distinct. For example, self-esteem is a general attitude toward the self that is fairly stable over time. It is not the same as mood, which is how good or bad one happens to be feeling right now. So people’s scores on a new measure of self-esteem should not be very highly correlated with their moods. If the new measure of self-esteem were highly correlated with a measure of mood, it could be argued that the new measure is not really measuring self-esteem; it is measuring mood instead.

When they created the Need for Cognition Scale, Cacioppo and Petty also provided evidence of discriminant validity by showing that people’s scores were not correlated with certain other variables. For example, they found only a weak correlation between people’s need for cognition and a measure of their cognitive style—the extent to which they tend to think analytically by breaking ideas into smaller parts or holistically in terms of “the big picture.” They also found no correlation between people’s need for cognition and measures of their test anxiety and their tendency to respond in socially desirable ways. All these low correlations provide evidence that the measure is reflecting a conceptually distinct construct.

- Cacioppo, J. T., & Petty, R. E. (1982). The need for cognition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 42, 116–131. ↵

- Petty, R. E, Briñol, P., Loersch, C., & McCaslin, M. J. (2009). The need for cognition. In M. R. Leary & R. H. Hoyle (Eds.), Handbook of individual differences in social behavior (pp. 318–329). New York, NY: Guilford Press. ↵

Refers to the consistency of a measure.

When researchers measure a construct that they assume to be consistent across time, then the scores they obtain should also be consistent across time.

The consistency of people’s responses across the items on a multiple-item measure.

A score that is derived by splitting the items into two sets and examining the relationship between the two sets of scores in order to assess the internal consistency of a measure.

The extent to which different observers are consistent in their judgments.

The extent to which the scores from a measure represent the variable they are intended to.

I can spend hours looking for articles online. I love browsing around and searching on Google Scholar for articles to download and read. However, I begin to feel overwhelmed once I realize that must read all the articles I've saved. It certainly takes a lot of time to do it correctly, even for faculty. In this chapter, we will learn how to understand and evaluate the sources you find. We will also review how your research questions might change as you start reading in your area of interest and learn more about your topic.

Chapter outline

- 3.1 Reading an empirical journal article

- 3.2 Evaluating sources

- 3.3 Refining your question

Content advisory

This chapter discusses or mentions the following topics: sexual harassment and gender-based violence, mental health, pregnancy, and obesity.

The extent to which people’s scores on a measure are correlated with other variables (known as criteria) that one would expect them to be correlated with.

Learning Objectives

- Critically evaluate the sources of the information you have found

- Apply the information from each source to your research proposal

- Identify how to be a responsible consumer of research

In Chapter 2, you developed a “working question” to guide your inquiry and learned how to use online databases to find sources. By now, you’ve hopefully collected a number of academic journal articles relevant to your topic area. It’s now time to evaluate the information you found. Not only do you want to be sure of the source and the quality of the information, but you also want to determine whether each item is an appropriate fit for your literature review.

This is also the point at which you make sure you have searched for and obtained publications for all areas of your research question and that you go back into the literature for another search, if necessary. You may also want to consult with your professor or the syllabus for your class to see what is expected for your literature review. In my class, I have specific questions I will ask students to address in their literature reviews.

It is likely that most of the resources you locate for your review will be from the scholarly literature of your discipline or your topic area. As we have already seen, peer-reviewed articles are written by and for experts in a field. They generally describe formal research studies or experiments with the purpose of providing insight on a topic. You may have located these articles through the four databases in Chapter 2 or through archival searching. You are now probably wondering how to evaluate the utility of the articles you've collected so you can use them for your research.

Generally, when we discuss the evaluation of sources, we are referring to the following aspects: accuracy, relevance, bias, reputation, currency, and credibility factors. These measures apply to all works, including books, ebooks, articles, websites, or blog postings to name a few. Before you include a source in your literature review, you should clearly understand what it is and why you are including it. According to Bennard et al. (2014), “Using inaccurate, irrelevant, or poorly researched sources can affect the quality of your own work” (para. 4). When evaluating a work for inclusion in, or exclusion from, your literature review, ask yourself a series of questions about each source.

-

- Is the information outdated? Is the source more than 5-10 years old? If so, it will not provide what we currently know about the topic--just what we used to know. Older sources are helpful for historical information, but unless historical analysis is the focus of your literature review, try to limit your sources to those that are current.

- How old are the sources used by the author? If you are reading an article from 10 years ago, they are likely citing material from 15-20 years ago. Again, this does not reflect what we currently know about a topic.

- Does the author have the credentials to write on the topic? Search the author’s name in a general web search engine like Google. What are the researcher’s academic credentials? What else has this author written? Search by author in the databases and see how much they have published on any given subject.

- Who published the source? Books published under popular press imprints (such as Random House or Macmillan) will not present scholarly research in the same way as Sage, Oxford, Harvard, or the University of Washington Press. For grey literature and websites, check the About Us page to learn more about potential biases and funding of the organization who wrote the report.

- Is the source relevant to your topic? How does the article fit into the scope of the literature on this topic? Does the information support your thesis or help you answer your question, or is it a challenge to make some kind of connection? Does the information present an opposite point of view, so you can show that you have addressed all sides of the argument in your paper? Many times, literature searches will include articles that ultimately are not that relevant to your final topic. You don’t need to read everything!

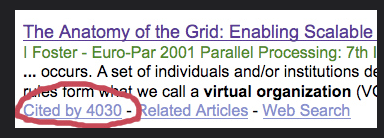

- How important is this source in the literature? If you search for the article on Google Scholar (see Figure 3.1 for an example of a search result from Google Scholar), you can see how many other sources cited this information. Generally, the higher the number of citations, the more important the article. This is a way to find seminal articles – “A classic work of research literature that is more than 5 years old and is marked by its uniqueness and contribution to professional knowledge” (Houser, 2018, p. 112).

Figure 3.1 Google Scholar - Is the source accurate? Check the facts in the article. Can statistics be verified through other sources? Does this information seem to fit with what you have read in other sources?

- Is the source reliable and objective? Is a particular point of view or bias immediately obvious, or does it seem objective at first glance? What point of view does the author represent? Are they clear about their point of view? Is the article an editorial that is trying to argue a position? Is the article in a publication with a particular editorial position?

- What is the scope of the article? Is it a general work that provides an overview of the topic or is it specifically focused on only one aspect of your topic?

- How strong is the evidence in the article? What are the research methods used in the article? Where does the method fall in the hierarchy of evidence?

- Meta-analysis and meta-synthesis: a systematic and scientific review that uses quantitative or qualitative methods (respectively) to summarize the results of many studies on a topic.

- Experiments and quasi-experiments: include a group of patients in an experimental group, as well as a control group. These groups are monitored for the variables/outcomes of interest. Randomized control trials are the gold standard.

- Longitudinal surveys: follow a group of people to identify how variables of interest change over time.

- Cross-sectional surveys: observe individuals at one point in time and discover relationships between variables.

- Qualitative studies: use in-depth interviews and analysis of texts to uncover the meaning of social phenomenon

The last point above comes with some pretty strong caveats, as no study is really better than another. Foremost, your research question should guide which kinds of studies you collect for your literature review. If you are conducting a qualitative study, you should include some qualitative studies in your literature review so you can understand how others have studied the topic before you. Even if you are conducting a quantitative study, qualitative research is important for understanding processes and lived experiences. Any article that demonstrates rigor in both thought and methodology is appropriate to use in your inquiry.

At the beginning of a project, you may not know what kind of research project you will ultimately propose. At this point, consulting a meta-analysis, meta-synthesis, or systematic review might be especially helpful as these articles try to summarize an entire body of literature into one article. Every type of source listed here is reputable, but some have greater explanatory power than others.

Thinking about your project

Two of the initial steps in designing a research project are identifying the overarching goals of your project and conducting a literature review. Forming a working research question, as discussed in section 2.1, is another crucial step. Creating and refining your research question will help you identify the key concepts you will study. Once you have identified those concepts, you’ll need to define them and decide how you will know that you are observing them during your data collection. Defining your concepts, and knowing them when you see them, relates to conceptualization and operationalization. Of course, you also need to know what approach you will take to collect your data. Thus, identifying your research method is another important part of research design.

In addition to identifying your research method, you also need to think about who your research participants will be and the larger group(s) they may represent. Last but certainly not least, you should consider any potential ethical concerns that could arise during the course of your research project. These concerns might come up during your data collection, but they might also arise when you get to the point of analyzing or sharing your research results.

Decisions about the various research components do not necessarily occur in sequential order. In fact, you may have to think about potential ethical concerns before you even zero in on a specific research question. Similarly, the goal of being able to make generalizations about your population of interest could shape the decisions you make about your method of data collection. Putting it all together, the following list shows some of the major components you’ll need to consider as you design your research project. Make sure you have information that will help inform how you think about each component.

- Research question

- Literature review

- Research strategy (idiographic or nomothetic, inductive or deductive)

- Units of analysis and units of observation

- Key concepts (conceptualization and operationalization)

- Method of data collection

- Research participants (sample and population)

- Ethical concerns

Being a responsible consumer of research

Being a responsible consumer of research requires you to take your identity as a social scientist seriously. Now that you are familiar with how to conduct research and how to read the results of others’ research, you have some responsibility to put your knowledge and skills to use. To do so, you must be able to distinguish what you know based on research from what you do not know. It is also a matter of having some awareness about what you can and cannot reasonably know as you encounter research findings.

When assessing social scientific findings, think about what information has been provided to you. In a scholarly journal article, you will presumably be given a great deal of information about the researcher’s method of data collection, her sample, and information about how she identified and recruited research participants. All of these details provide important contextual information that can help you assess the researcher’s claims. On the other hand, a discussion of social scientific research in a popular magazine or newspaper will likely fail to provide the same level of detailed information. In this case, what you do and do not know is more limited than in the case of a scholarly journal article. If the research appears in popular media, search for the author or study title in an academic database.

Also, take into account whatever information is provided about a study’s funding source. Most times, the entities that fund a study require that they are acknowledged in the publication, but more popular press may leave out a funding source. In this Internet age, it can be relatively easy to obtain information about how a study was funded. If this information is not provided in the source from which you learned about a study, it might behoove you to do a quick search on the web to see if you can learn more about a researcher’s funding. Findings that seem to support a particular political agenda, for example, might have more or less weight once you know whether and by whom a study was funded.

There is some information that even the most responsible consumer of research cannot know. Because researchers are ethically bound to protect the identities of their subjects, for example, we will never know exactly who participated in a given study. Researchers may also choose not to reveal any personal stakes they hold in the research they conduct. While researchers may “start where they are,” we cannot know for certain whether or how researchers are personally connected to their work unless they choose to share such details. Neither of these “unknowables” are necessarily problematic, but having some awareness of what you may never know about a study does provide important contextual information from which to assess what one can “take away” from a given report of findings.

Key Takeaways

- Not all published articles are the same. Evaluating sources requires a careful investigation of each source.

- Being a responsible consumer of research means giving serious thought and understanding to what you do know, what you don’t know, what you can know, and what you can’t know.

Image attributions

130329-A-XX000-001 by Master Sgt. Michael Chann public domain

Learning Objectives

- Explain how information is created and how it evolves over time

- Select appropriate sources for your inquiry

- Describe the strengths and limitations of each type of source

Because a literature review is a summary and analysis of the relevant publications on a topic, we first have to understand what is meant by “the literature.” In this case, “the literature” is a collection of all of the relevant written sources on a topic.

Disciplines of knowledge

When drawing boundaries around an idea, topic, or subject area, it is helpful to think about how and where the information for the field is produced. For this, you need to identify the disciplines of knowledge production in a subject area.

Information does not exist in the environment like some kind of raw material, rather it is produced by individuals working within a particular field of knowledge who use specific methods for generating new information. Disciplines consume, produce, and disseminate knowledge. Looking through a university’s course catalog gives clues to disciplinary structure. Fields such as political science, biology, history, and mathematics are unique disciplines, as is social work. Each has its own logic for how and where new knowledge is introduced and made accessible.

You will need to become comfortable with identifying the disciplines that might contribute information to any search. When you do this, you will also learn how to decode the way people talk about a topic within certain disciplines. This will be useful when you begin a review of the literature in your area of study.

For example, think about the disciplines that might contribute information to a topic such as the role of sports in society. Try to anticipate the type of perspective each discipline might have on the topic. Consider the following types of questions as you examine what different disciplines might contribute:

- What is important about the topic to the people in that discipline?

- What is most likely to be the focus of their study about the topic?

- What perspective would they be likely to have on the topic?

In this example, we identify two disciplines that have something to say about the role of sports in society: the human service professions of nursing and social work. What would each of these disciplines raise as key questions or issues related to that topic? A nursing researcher might study how sports affect individuals' health and well-being, how to assess and treat sports injuries, or the physical conditioning required for athletics. A social work researcher might study how schools privilege or punish student athletes, how athletics impact social relationships and hierarchies, or the differences between boys' and girls' participation in organized sports. In this example, we see that a single topic can be approached from many different perspectives depending on how the disciplinary boundaries are drawn and how the topic is framed. Nevertheless, it is useful for a social worker to be aware of the nursing literature, as they could better appreciate the physical toll that sports take on athletes' bodies and how that may interact with other issues. An interdisciplinary perspective is usually a more comprehensive perspective.

Types of sources

“The literature” consists of the published works that document a scholarly conversation on a specific topic within and between disciplines. In “the literature,” you will find documents that explain the background of your topic. You will also find controversies and unresolved questions that can inspire your own project. By now in your social work academic career, you’ve probably heard that you need to get “peer-reviewed journal articles.” But what are those exactly? How do they differ from news articles or encyclopedias? This section of the text will help you to differentiate the different types of literature.

First, let’s discuss periodicals. Periodicals include journals, trade publications, magazines, and newspapers. While they may appear similar, particularly online, each of these periodicals has unique features designed for a specific purpose. Magazine and newspaper articles are usually written by journalists. They are intended to be short and understandable for the average adult, they contain color images and advertisements, and they are designed as commodities to be sold to an audience. Magazines may contain primary or secondary literature depending on the article in question. The New Social Worker is an excellent magazine for social workers. An article that is a primary source would gather information as an event happened, like an interview with a victim of a local fire, or relate original research done by the journalists, like the Guardian newspaper’s The Counted webpage which tracks how many people were killed by police officers in the United States. [2]

You may be wondering if magazines are acceptable sources of information in a research methods course. If you were in my class, I would advise against using magazines as sources. There are some exceptions like the Guardian page mentioned above or breaking news about a policy or community, but I advise against using magazines and newspapers because most of the information they publish is secondary literature. Secondary sources interpret, discuss, and summarize primary sources. Often, news articles will summarize a study done in an academic journal. Your job in this course is to read the original source of the information, in this case, the academic journal article itself. Journalists are not scientists. If you have seen articles about how chocolate cures cancer or how drinking whiskey can extend your life, you should understand how journalists can exaggerate or misinterpret results. Careful scholars will critically examine the primary source, rather than relying on someone else’s summary. Many newspapers and magazines also contain opinion articles, which are even less reputable, as the author will choose facts to support their viewpoint and exclude facts that contract their viewpoint. Nevertheless, newspaper and magazine articles are excellent places to start your journey into the literature, as they do not require specialized knowledge to understand and may inspire deeper inquiry.

Unlike magazines and newspapers, trade publications may take some specialized knowledge to understand. Trade publications or trade journals are periodicals directed to members of a specific profession. They often have information about industry trends and practical information for people working in the field. Trade publications are somewhat more reputable than newspapers or magazines because the authors are specialists on their field. NASW News is a good example of a trade publication in social work, published by the National Association of Social Workers. Its intended audience is social work practitioners who want to know about important practice issues. They report news and trends in a field but not scholarly research. They may also provide product or service reviews, job listings, and advertisements.

So, can you use trade publications in a formal research proposal? In my class, I would advise against it, as a main shortcoming of trade publications is their lack of peer review. Peer review refers to a formal process in which other esteemed researchers and experts ensure your work meets the standards and expectations of the professional field. While trade publications do contain a staff of editors, the level of review is not as stringent as academic journal articles. On the other hand, if you are doing a study about practitioners, then trade publications may be quite relevant sources for your proposal. As illustrated below, peer review is the part of the publication cycle that acts as the gate-keeper to ensure that only top-quality articles are published. While peer review is far from perfect, the process provides for stricter scrutiny of scientific publications.

In summary, newspapers and other popular press publications are useful for getting general topic ideas. Trade publications are useful for practical application in a profession and may also be a good source of keywords for future searching. Scholarly journals are the conversation of the scholars who are doing research in a specific discipline and publishing their research findings.

Types of journal articles

As you’ve probably heard by now, academic journal articles are regarded as the most reputable sources of information, particularly in research methods courses. Journal articles are written by scholars with the intended audience of other scholars (like you!) interested in the subject matter. The articles are often long and contain extensive references for the arguments made by the author. The journals themselves are often dedicated to a single topic, like violence or child welfare, and include articles that seek to advance the body of knowledge about their chosen topic.

Most journals are peer-reviewed or refereed, which means a panel of scholars reviews articles to decide if they should be accepted into a specific publication. Scholarly journals provide articles of interest to experts or researchers in a discipline. An editorial board of respected scholars (peers) reviews all articles submitted to a journal. Editors and volunteer reviewers decide if the article provides a noteworthy contribution to the field and if it should be published. For this reason, journal articles are the main source of information for researchers and for literature reviews. You can tell whether a journal is peer reviewed by going to its website. Usually, under the “About Us” section, the website will list the editorial board or otherwise note its procedures for peer review. If a journal does not provide such information, you may have found a “predatory journal.” These journals will publish any article—no matter how bad it is—as long as the author pays them. Not all journals are created equal!

A kind of peer review also occurs after publication. Scientists regularly read articles and use them to inform their research. A seminal article is “a classic work of research literature that is more than 5 years old and is marked by its uniqueness and contribution to professional knowledge” (Houser, 2018, p. 112). [3] Basically, it is a really important article. Seminal articles are cited a lot in the literature. You can see how many authors have cited an article using Google Scholar’s citation count feature when you search for the article. Generally speaking, articles that have been cited more often are considered more reputable. There is nothing wrong with citing an article with a low citation count, but it is an indication that not many other scholars have found the source to be useful or important.

Journal articles fall into a few different categories. Empirical articles apply theory to a behavior and reports the results of a quantitative or qualitative data analysis conducted by the author. Just because an article includes quantitative or qualitative results does not mean it is an empirical journal article. Since most articles contain a literature review with empirical findings, you need to make sure the findings reported in the study are from the author’s own analysis. Fortunately, empirical articles follow a similar structure—introduction, method, results, and discussion sections appear in that order. While the exact headings may differ slightly from publication to publication and other sections like conclusions, implications, or limitations may appear, this general structure applies to nearly all empirical journal articles.

Theoretical articles, by contrast, do not follow a set structure. They follow whatever format the author finds most useful to organize their information. Theoretical articles discuss a theory, conceptual model, or framework for understanding a problem. They may delve into philosophy or values, as well. Theoretical articles help you understand how to think about a topic and may help you make sense of the results of empirical studies. Practical articles describe “how things are done” (Wallace & Wray, 2016, p. 20). [4] They are usually shorter than other types of articles and are intended to inform practitioners of a discipline on current issues. They may also provide a reflection on a “hot topic” in the practice domain, a complex client situation, or an issue that may affect the profession as a whole.

No one type of article is better than the other, as each serves a different purpose. Seminal articles relevant to your topic area are important to read because of their influence on the field. Theoretical articles will help you understand the social theory behind your topic. Empirical articles should test those theories quantitatively or create those theories qualitatively, a process we will discuss in greater detail later in this book. Practical articles will help you understand a practitioner’s perspective, though these are less useful when writing a literature review, as they only present a single person’s opinions on a topic.

Other sources of information

As mentioned earlier, newspaper and magazine articles are good places to start your search, though they should not be the end of your search. Another source that students commonly flock to is Wikipedia. Wikipedia is a marvel of human knowledge, as anyone can contribute to the digital encyclopedia. The entries for each Wikipedia article are overseen by skilled and specialized editors who volunteer their time and knowledge to making sure their articles are correct and up to date. Wikipedia is an example of a tertiary source. We reviewed primary and secondary sources in the previous section. Tertiary sources synthesize or distill primary and secondary sources. Examples of tertiary sources include encyclopedias, directories, dictionaries, and textbooks like this one. Tertiary sources are an excellent place to start, but are not a good place to end your search. A student might consult Wikipedia or the Encyclopedia of Social Work (available at http://socialwork.oxfordre.com/) to get a general idea of the topic.

As we’ve discussed, secondary and tertiary sources are great places to begin gathering background information on a topic, but as your study of the topic progresses towards your research project, you will have to begin using primary sources. Academic journal articles are one of the primary sources that we will discuss the most in this textbook, as they are an excellent source to use in formal research papers. However, it is important to understand how other types of sources can be utilized as well.

Books contain important scholarly information. They are particularly helpful for theoretical, philosophical, and historical inquiry. For example, in my research on self-determination for individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities, I needed to define and explore the concept of self-determination. I learned how to define it from the philosophical literature on self-determination and the advocacy literature contained in books. You can use books to learn definitions and key concepts, to identify keywords, and to find additional resources for further information. They will also help you to understand the scope of the topic, its underlying foundations, and how the topic has developed over time.

You may notice that some books contain chapters that resemble academic journal articles. These are called edited volumes, and they contain articles that may not have made it into academic journals or seminal articles that are republished in the book. Edited volumes are considered less reputable than journal articles, as they do not have as strong of a peer review process. However, papers in social science journals will often include references to books and edited volumes.

In addition to peer-reviewed academic journal articles and books, conferences are another great source of information. At conferences such as the Council on Social Work Education’s Annual Program Meeting or your state’s NASW conference, researchers present papers on their most recent research and obtain feedback from the audience. The papers presented at conferences are sometimes published in a volume called a conference proceeding, which highlights current discussions in a discipline and can lead you to scholars who are interested in specific research areas. If you are looking to use a conference proceeding as a source for your research paper, it is important to note that several factors can make them particularly difficult to find. Papers that are delivered at professional conferences are not always fully published in print or electronic form. The abstract of a paper may be available; however the full paper may only be available to the author(s). If you have any difficulty accessing a conference proceeding or paper, ask a librarian for assistance.

Another source of information is the gray literature, which is research and information released by non-commercial publishers, such as government agencies, policy organizations, and think-tanks. If you have already taken a policy class, perhaps you’ve come across the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (https://www.cbpp.org/). CBPP is a think tank, or a group of scholars, that conducts research and performs advocacy on social issues. Similarly, students often find the Centers for Disease Control website helpful for understanding the prevalence of social problems like mental illness and child abuse.

It is important to note that there are potential limitations to using gray literature as a source, such as the potential for biased information. Typically, think tanks and policy organizations have a specific viewpoint that they support. For example, there are conservative, liberal, and libertarian think tanks and policy organizations may be funded by private businesses to push a given message to the public. On the other hand, government agencies are generally more objective, though they may be less critical in their opinions of government programs than other sources. The main shortcoming of gray literature is the lack of peer review that is found in academic journal articles, though many gray literature sources are of good quality.

Additional sources of gray literature include dissertations and theses. These two sources are rich, and they often contain extensive reference lists that you can scan for further resources, however they are considered gray literature because they are not peer reviewed. The accuracy and validity of the paper itself may depend on the school that awarded the doctoral or master’s degree to the author. Having completed a dissertation myself, I know that they take a long time to write and a long time to read through. If you come across a dissertation that is relevant, it is a good idea to read the literature review and plumb the sources the author uses in your literature search. However, the data analysis from these sources is considered less reputable as it has not passed through peer review yet. Consider searching for journal articles by the author to see if any of the results passed peer review. You will also be thankful that journal articles are much shorter than dissertations and theses!

The final source of information we must talk about is webpages. My graduate research focused on substance abuse and drugs, and I was fond of reading Drug War Rant (http://www.drugwarrant.com/), a blog about drug policy. It provided me with breaking news about drug policy and editorial opinion about the drug war. I would never cite the blog in a research proposal, but it was an excellent source of information that warranted further investigation. Webpages will also help you locate professional organizations and human service agencies that address your research topic. The website of an organization may include social media feeds, reports, publications, or “news” sections that can clue you into important topics to study. Because anyone can begin their own webpage, they are usually not considered scholarly sources to use in formal writing, but they are still useful when you are first learning about a topic. Additionally, many advocacy webpages will provide references for the facts they cite, providing you with the primary source of the information.

As you think about each source, remember:

All information sources are not created equal. Sources can vary greatly in terms of how carefully they are researched, written, edited, and reviewed for accuracy. Common sense will help you identify obviously questionable sources, such as tabloids that feature tales of alien abductions, or personal websites with glaring typos. Sometimes, however, a source’s reliability—or lack of it—is not so obvious…You will consider criteria such as the type of source, its intended purpose and audience, the author’s (or authors’) qualifications, the publication’s reputation, any indications of bias or hidden agendas, how current the source is, and the overall quality of the writing, thinking, and design. (Writing for Success, 2015, p. 448). [5]

While each of these sources is an important part of how we learn about a topic, your research should focus on finding academic journal articles about your topic. These are the primary sources of the research world. While it may be acceptable and necessary to use other primary sources—like books, government reports, or an investigative article by a newspaper or magazine—academic journal articles are preferred. Finding these journal articles is the topic of the next section.

Key Takeaways

- Social work involves reading research from a variety of disciplines.

- While secondary and tertiary sources are okay to start with, primary sources provide the most accurate and authoritative information about a topic.

- Peer-reviewed journal articles are considered the best source of information for literature reviews, though other sources are often used.

- Peer review is the process by which other scholars evaluate the merits of an article before publication.

- Social work research requires critical evaluation of each source in a literature review

Glossary

Empirical articles- apply theory to a behavior and report the results of a quantitative or qualitative data analysis conducted by the author

Gray literature- research and information released by non-commercial publishers, such as government agencies, policy organizations, and think-tanks

Peer review- a formal process in which other esteemed researchers and experts ensure your work meets the standards and expectations of the professional field

Practical articles- describe “how things are done” in practice (Wallace & Wray, 2016, p. 20)

Primary source- published results of original research studies

Secondary source- interpret, discuss, summarize original sources

Seminal articles– classic work noted for its contribution to the field and its high citation count

Tertiary source- synthesizes or distills primary and secondary sources, such as Wikipedia

Theoretical articles– articles that discuss a theory, conceptual model or framework for understanding a problem

Image Attributions

Yahoo news portal by Simon CC-0

Research journals by M. Imran CC-0

Books door entrance culture by ninocare CC-0