31 Qualitative Research

Learning Objectives

- List several ways in which qualitative research differs from quantitative research in psychology.

- Describe the strengths and weaknesses of qualitative research in psychology compared with quantitative research.

- Give examples of qualitative research in psychology.

What Is Qualitative Research?

This textbook is primarily about quantitative research, in part because most studies conducted in psychology are quantitative in nature. Quantitative researchers typically start with a focused research question or hypothesis, collect a small amount of numerical data from a large number of individuals, describe the resulting data using statistical techniques, and draw general conclusions about some large population. Although this method is by far the most common approach to conducting empirical research in psychology, there is an important alternative called qualitative research. Qualitative research originated in the disciplines of anthropology and sociology but is now used to study psychological topics as well. Qualitative researchers generally begin with a less focused research question, collect large amounts of relatively “unfiltered” data from a relatively small number of individuals, and describe their data using nonstatistical techniques, such as grounded theory, thematic analysis, critical discourse analysis, or interpretative phenomenological analysis. They are usually less concerned with drawing general conclusions about human behavior than with understanding in detail the experience of their research participants.

Consider, for example, a study by researcher Per Lindqvist and his colleagues, who wanted to learn how the families of teenage suicide victims cope with their loss (Lindqvist, Johansson, & Karlsson, 2008)[1]. They did not have a specific research question or hypothesis, such as, What percentage of family members join suicide support groups? Instead, they wanted to understand the variety of reactions that families had, with a focus on what it is like from their perspectives. To address this question, they interviewed the families of 10 teenage suicide victims in their homes in rural Sweden. The interviews were relatively unstructured, beginning with a general request for the families to talk about the victim and ending with an invitation to talk about anything else that they wanted to tell the interviewer. One of the most important themes that emerged from these interviews was that even as life returned to “normal,” the families continued to struggle with the question of why their loved one committed suicide. This struggle appeared to be especially difficult for families in which the suicide was most unexpected.

The Purpose of Qualitative Research

Again, this textbook is primarily about quantitative research in psychology. The strength of quantitative research is its ability to provide precise answers to specific research questions and to draw general conclusions about human behavior. This method is how we know that people have a strong tendency to obey authority figures, for example, and that female undergraduate students are not substantially more talkative than male undergraduate students. But while quantitative research is good at providing precise answers to specific research questions, it is not nearly as good at generating novel and interesting research questions. Likewise, while quantitative research is good at drawing general conclusions about human behavior, it is not nearly as good at providing detailed descriptions of the behavior of particular groups in particular situations. And quantitative research is not very good at communicating what it is actually like to be a member of a particular group in a particular situation.

But the relative weaknesses of quantitative research are the relative strengths of qualitative research. Qualitative research can help researchers to generate new and interesting research questions and hypotheses. The research of Lindqvist and colleagues, for example, suggests that there may be a general relationship between how unexpected a suicide is and how consumed the family is with trying to understand why the teen committed suicide. This relationship can now be explored using quantitative research. But it is unclear whether this question would have arisen at all without the researchers sitting down with the families and listening to what they themselves wanted to say about their experience. Qualitative research can also provide rich and detailed descriptions of human behavior in the real-world contexts in which it occurs. Among qualitative researchers, this depth is often referred to as “thick description” (Geertz, 1973)[2]. Similarly, qualitative research can convey a sense of what it is actually like to be a member of a particular group or in a particular situation—what qualitative researchers often refer to as the “lived experience” of the research participants. Lindqvist and colleagues, for example, describe how all the families spontaneously offered to show the interviewer the victim’s bedroom or the place where the suicide occurred—revealing the importance of these physical locations to the families. It seems unlikely that a quantitative study would have discovered this detail.

Table 6.3 Some contrasts between qualitative and quantitative research

| Qualitative | Quantitative |

|

1. In-depth information about relatively few people

|

1. Less depth information with larger samples

|

|

2. Conclusions are based on interpretations drawn by the investigator

|

2. Conclusions are based on statistical analyses

|

|

3. Global and exploratory

|

3. Specific and focused

|

Data Collection and Analysis in Qualitative Research

Data collection approaches in qualitative research are quite varied and can involve naturalistic observation, participant observation, archival data, artwork, and many other things. But one of the most common approaches, especially for psychological research, is to conduct interviews. Interviews in qualitative research can be unstructured—consisting of a small number of general questions or prompts that allow participants to talk about what is of interest to them—or structured, where there is a strict script that the interviewer does not deviate from. Most interviews are in between the two and are called semi-structured interviews, where the researcher has a few consistent questions and can follow up by asking more detailed questions about the topics that come up. Such interviews can be lengthy and detailed, but they are usually conducted with a relatively small sample. The unstructured interview was the approach used by Lindqvist and colleagues in their research on the families of suicide victims because the researchers were aware that how much was disclosed about such a sensitive topic should be led by the families, not by the researchers.

Another approach used in qualitative research involves small groups of people who participate together in interviews focused on a particular topic or issue, known as focus groups. The interaction among participants in a focus group can sometimes bring out more information than can be learned in a one-on-one interview. The use of focus groups has become a standard technique in business and industry among those who want to understand consumer tastes and preferences. The content of all focus group interviews is usually recorded and transcribed to facilitate later analyses. However, we know from social psychology that group dynamics are often at play in any group, including focus groups, and it is useful to be aware of those possibilities. For example, the desire to be liked by others can lead participants to provide inaccurate answers that they believe will be perceived favorably by the other participants. The same may be said for personality characteristics. For example, highly extraverted participants can sometimes dominate discussions within focus groups.

Data Analysis in Qualitative Research

Although quantitative and qualitative research generally differ along several important dimensions (e.g., the specificity of the research question, the type of data collected), it is the method of data analysis that distinguishes them more clearly than anything else. To illustrate this idea, imagine a team of researchers that conducts a series of unstructured interviews with people recovering from alcohol use disorder to learn about the role of their religious faith in their recovery. Although this project sounds like qualitative research, imagine further that once they collect the data, they code the data in terms of how often each participant mentions God (or a “higher power”), and they then use descriptive and inferential statistics to find out whether those who mention God more often are more successful in abstaining from alcohol. Now it sounds like quantitative research. In other words, the quantitative-qualitative distinction depends more on what researchers do with the data they have collected than with why or how they collected the data.

But what does qualitative data analysis look like? Just as there are many ways to collect data in qualitative research, there are many ways to analyze data. Here we focus on one general approach called grounded theory (Glaser & Strauss, 1967)[3]. This approach was developed within the field of sociology in the 1960s and has gradually gained popularity in psychology. Remember that in quantitative research, it is typical for the researcher to start with a theory, derive a hypothesis from that theory, and then collect data to test that specific hypothesis. In qualitative research using grounded theory, researchers start with the data and develop a theory or an interpretation that is “grounded in” those data. They do this analysis in stages. First, they identify ideas that are repeated throughout the data. Then they organize these ideas into a smaller number of broader themes. Finally, they write a theoretical narrative—an interpretation of the data in terms of the themes that they have identified. This theoretical narrative focuses on the subjective experience of the participants and is usually supported by many direct quotations from the participants themselves.

As an example, consider a study by researchers Laura Abrams and Laura Curran, who used the grounded theory approach to study the experience of postpartum depression symptoms among low-income mothers (Abrams & Curran, 2009)[4]. Their data were the result of unstructured interviews with 19 participants. Table 6.4 shows the five broad themes the researchers identified and the more specific repeating ideas that made up each of those themes. In their research report, they provide numerous quotations from their participants, such as this one from “Destiny:”

Well, just recently my apartment was broken into and the fact that his Medicaid for some reason was cancelled so a lot of things was happening within the last two weeks all at one time. So that in itself I don’t want to say almost drove me mad but it put me in a funk.…Like I really was depressed. (p. 357)

Their theoretical narrative focused on the participants’ experience of their symptoms, not as an abstract “affective disorder” but as closely tied to the daily struggle of raising children alone under often difficult circumstances.

| Theme | Repeating ideas |

| Ambivalence | “I wasn’t prepared for this baby,” “I didn’t want to have any more children.” |

| Caregiving overload | “Please stop crying,” “I need a break,” “I can’t do this anymore.” |

| Juggling | “No time to breathe,” “Everyone depends on me,” “Navigating the maze.” |

| Mothering alone | “I really don’t have any help,” “My baby has no father.” |

| Real-life worry | “I don’t have any money,” “Will my baby be OK?” “It’s not safe here.” |

The Quantitative-Qualitative “Debate”

Given their differences, it may come as no surprise that quantitative and qualitative research in psychology and related fields do not coexist in complete harmony. Some quantitative researchers criticize qualitative methods on the grounds that they lack objectivity, are difficult to evaluate in terms of reliability and validity, and do not allow generalization to people or situations other than those actually studied. At the same time, some qualitative researchers criticize quantitative methods on the grounds that they overlook the richness of human behavior and experience and instead answer simple questions about easily quantifiable variables.

In general, however, qualitative researchers are well aware of the issues of objectivity, reliability, validity, and generalizability. In fact, they have developed a number of frameworks for addressing these issues (which are beyond the scope of our discussion). And in general, quantitative researchers are well aware of the issue of oversimplification. They do not believe that all human behavior and experience can be adequately described in terms of a small number of variables and the statistical relationships among them. Instead, they use simplification as a strategy for uncovering general principles of human behavior.

Many researchers from both the quantitative and qualitative camps now agree that the two approaches can and should be combined into what has come to be called mixed-methods research (Todd, Nerlich, McKeown, & Clarke, 2004)[5]. (In fact, the studies by Lindqvist and colleagues and by Abrams and Curran both combined quantitative and qualitative approaches.) One approach to combining quantitative and qualitative research is to use qualitative research for hypothesis generation and quantitative research for hypothesis testing. Again, while a qualitative study might suggest that families who experience an unexpected suicide have more difficulty resolving the question of why, a well-designed quantitative study could test a hypothesis by measuring these specific variables in a large sample. A second approach to combining quantitative and qualitative research is referred to as triangulation. The idea is to use both quantitative and qualitative methods simultaneously to study the same general questions and to compare the results. If the results of the quantitative and qualitative methods converge on the same general conclusion, they reinforce and enrich each other. If the results diverge, then they suggest an interesting new question: Why do the results diverge and how can they be reconciled?

Using qualitative research can often help clarify quantitative results via triangulation. Trenor, Yu, Waight, Zerda, and Sha (2008)[6] investigated the experience of female engineering students at a university. In the first phase, female engineering students were asked to complete a survey, where they rated a number of their perceptions, including their sense of belonging. Their results were compared across the student ethnicities, and statistically, the various ethnic groups showed no differences in their ratings of their sense of belonging. One might look at that result and conclude that ethnicity does not have anything to do with one’s sense of belonging. However, in the second phase, the authors also conducted interviews with the students, and in those interviews, many minority students reported how the diversity of cultures at the university enhanced their sense of belonging. Without the qualitative component, we might have drawn the wrong conclusion about the quantitative results.

This example shows how qualitative and quantitative research work together to help us understand human behavior. Some researchers have characterized qualitative research as best for identifying behaviors or the phenomenon whereas quantitative research is best for understanding meaning or identifying the mechanism. However, Bryman (2012)[7] argues for breaking down the divide between these arbitrarily different ways of investigating the same questions.

- Lindqvist, P., Johansson, L., & Karlsson, U. (2008). In the aftermath of teenage suicide: A qualitative study of the psychosocial consequences for the surviving family members. BMC Psychiatry, 8, 26. Retrieved from http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-244X/8/26 ↵

- Geertz, C. (1973). The interpretation of cultures. New York, NY: Basic Books. ↵

- Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Chicago, IL: Aldine. ↵

- Abrams, L. S., & Curran, L. (2009). “And you’re telling me not to stress?” A grounded theory study of postpartum depression symptoms among low-income mothers. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 33, 351–362. ↵

- Todd, Z., Nerlich, B., McKeown, S., & Clarke, D. D. (2004) Mixing methods in psychology: The integration of qualitative and quantitative methods in theory and practice. London, UK: Psychology Press. ↵

- Trenor, J.M., Yu, S.L., Waight, C.L., Zerda. K.S & Sha T.-L. (2008). The relations of ethnicity to female engineering students’ educational experiences and college and career plans in an ethnically diverse learning environment. Journal of Engineering Education, 97(4), 449-465. ↵

- Bryman, A. (2012). Social Research Methods, 4th ed. Oxford: OUP. ↵

Research that typically starts with a focused research question or hypothesis, collects a small amount of numerical data from a large number of individuals, describes the resulting data using statistical techniques, and draws general conclusions about some large population.

Research that begins with a less focused research question, collects large amounts of relatively “unfiltered” data from a relatively small number of individuals, describes data using nonstatistical techniques, such as grounded theory, thematic analysis, critical discourse analysis, or interpretative phenomenological analysis and aims to understand in detail the experience of the research participants.

Learning Objectives

- Define and describe informed consent

- Identify the unique concerns related to studying vulnerable populations

- Differentiate between anonymity and confidentiality

- Explain the ethical responsibilities of social workers conducting research

As should be clear by now, conducting research on humans presents a number of unique ethical considerations. Human research subjects must be given the opportunity to consent to their participation, after being fully informed of the study's risks, benefits, and purpose. Further, subjects’ identities and the information they share should be protected by researchers. Of course, the definitions of consent and identity protection may vary by individual researcher, institution, or academic discipline. In section 5.1, we examined the role that institutions play in shaping research ethics. In this section, we’ll look at a few specific topics that individual researchers and social workers must consider before conducting research with human subjects.

Informed consent

All social work research projects involve the voluntary participation of all human subjects. In other words, we cannot force anyone to participate in our research without their knowledge and consent, unlike the experiment in Truman Show. Researchers must therefore design procedures to obtain subjects’ informed consent to participate in their research. Informed consent is defined as a subject’s voluntary agreement to participate in research based on a full understanding of the research and of the possible risks and benefits involved. Although it sounds simple, ensuring that one has actually obtained informed consent is a much more complex process than you might initially presume.

The first requirement to obtain informed consent is that participants may neither waive nor even appear to waive any of their legal rights. In addition, if something were to go wrong during their participation in research, participants cannot release the researcher, the researcher's sponsor, or any institution from any legal liability (USDHHS, 2009). [1] Unlike biomedical research, for example, social work research does not typically involve asking subjects to place themselves at risk of physical harm. Because of this, social work researchers often do not have to worry about potential liability, however their research may involve other types of risks.

For example, what if a social work researcher fails to sufficiently conceal the identity of a subject who admits to participating in a local swinger’s club? In this case, a violation of confidentiality may negatively affect the participant’s social standing, marriage, custody rights, or employment. Social work research may also involve asking about intimately personal topics, such as trauma or suicide that may be difficult for participants to discuss. Participants may re-experience traumatic events and symptoms when they participate in your study. Even after fully informing the participants of all risks before they consent to the research process, there is the possibility of raising difficult topics that prove overwhelming for participants. In cases like these, it is important for a social work researcher to have a plan to provide supports, such as referrals to community counseling or even calling the police if the participant is a danger to themselves or others.

It is vital that social work researchers craft their consent forms to fully explain their mandatory reporting duties and ensure that subjects understand the terms before participating. Researchers should also emphasize to participants that they can stop the research process at any time or decide to withdraw from the research study for any reason. Importantly, it is not the job of the social work researcher to act as a clinician to the participant. While a supportive role is certainly appropriate for someone experiencing a mental health crisis, social workers must ethically avoid dual roles. Referring a participant in crisis to other mental health professionals who may be better able to help them is preferred.

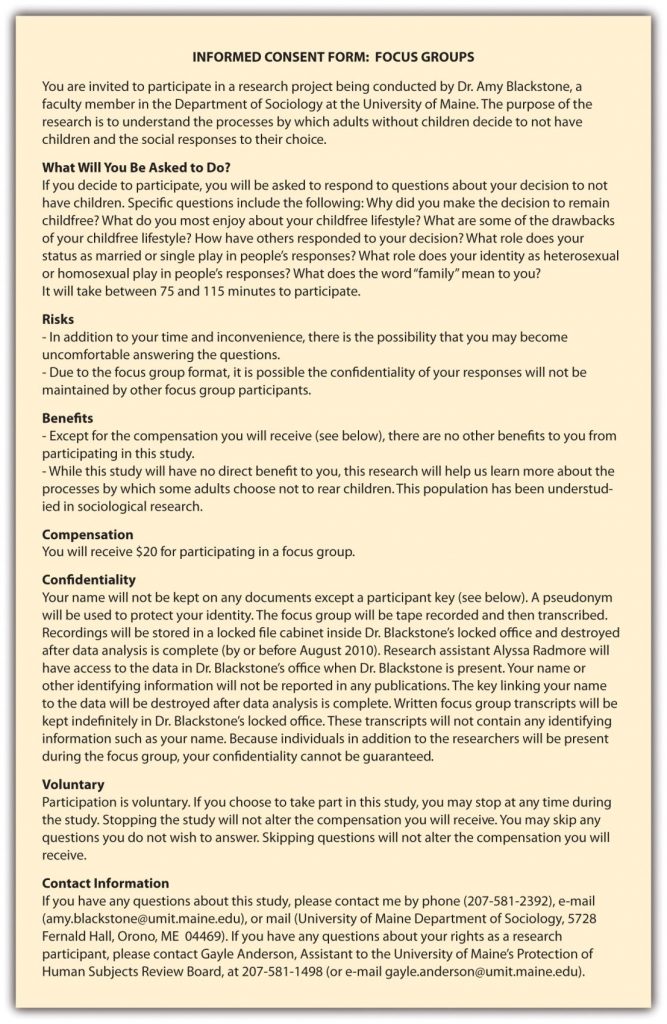

In addition to legal issues, most IRBs are also concerned with details of the research, including: the purpose of the study, possible benefits of participation, and most importantly, potential risks of participation. Further, researchers must describe how they will protect subjects’ identities, all details regarding data collection and storage, and provide a contact reached for additional information about the study and the subjects’ rights. All of this information is typically shared in an informed consent form that researchers provide to subjects. In some cases, subjects are asked to sign the consent form indicating that they have read it and fully understand its contents. In other cases, subjects are simply provided a copy of the consent form and researchers are responsible for making sure that subjects have read and understand the form before proceeding with any kind of data collection. Figure 5.1 showcases a sample informed consent form taken from a research project on child-free adults. Note that this consent form describes a risk that may be unique to the particular method of data collection being employed: focus groups.

When preparing to obtain informed consent, it is important to consider that not all potential research subjects are considered equally competent or legally allowed to consent to participate in research. Subjects from vulnerable populations may be at risk of experiencing undue influence or coercion. [3] The rules for consent are more stringent for vulnerable populations. For example, minors must have the consent of a legal guardian in order to participate in research. In some cases, the minors themselves are also asked to participate in the consent process by signing special, age-appropriate consent forms. Vulnerable populations raise many unique concerns because they may not be able to fully consent to research participation. Researchers must be concerned with the potential for underrepresentation of vulnerable groups in studies. On one hand, researchers must ensure that their procedures to obtain consent are not coercive, as the informed consent process can be more rigorous for these groups. On the other hand, researchers must also work to ensure members of vulnerable populations are not excluded from participation simply because of their vulnerability or the complexity of obtaining their consent. While there is no easy solution to this double-edged sword, an awareness of the potential concerns associated with research on vulnerable populations is important for identifying whatever solution is most appropriate for a specific case.

Protection of identities

As mentioned earlier, the informed consent process requires researchers to outline how they will protect the identities of subjects. This aspect of the process, however, is one of the most commonly misunderstood aspects of research.

In protecting subjects’ identities, researchers typically promise to maintain either the anonymity or confidentiality of their research subjects. Anonymity is the more stringent of the two. When a researcher promises anonymity to participants, not even the researcher is able to link participants’ data with their identities. Anonymity may be impossible for some social work researchers to promise because several of the modes of data collection that social workers employ. Face-to-face interviewing means that subjects will be visible to researchers and will hold a conversation, making anonymity impossible. In other cases, the researcher may have a signed consent form or obtain personal information on a survey and will therefore know the identities of their research participants. In these cases, a researcher should be able to at least promise confidentiality to participants.

Offering confidentiality means that some of the subjects' identifying information is known and may be kept, but only the researcher can link identity to data with the promise to keep this information private. Confidentiality in research and clinical practice are similar in that you know who your clients are, but others do not, and you promise to keep their information and identity private. As you can see under the “Risks” section of the consent form in Figure 5.1, sometimes it is not even possible to promise that a subject’s confidentiality will be maintained. This is the case if data collection takes place in public or in the presence of other research participants, like in a focus group study. Social workers also cannot promise confidentiality in cases where research participants pose an imminent danger to themselves or others, or if they disclose abuse of children or other vulnerable populations. These situations fall under a social worker’s duty to report, which requires the researcher to prioritize their legal obligations over participant confidentiality.

Protecting research participants’ identities is not always a simple prospect, especially for those conducting research on stigmatized groups or illegal behaviors. Sociologist Scott DeMuth learned how difficult this task was while conducting his dissertation research on a group of animal rights activists. As a participant observer, DeMuth knew the identities of his research subjects. When some of his research subjects vandalized facilities and removed animals from several research labs at the University of Iowa, a grand jury called on Mr. DeMuth to reveal the identities of the participants in the raid. When DeMuth refused to do so, he was jailed briefly and then charged with conspiracy to commit animal enterprise terrorism and cause damage to the animal enterprise (Jaschik, 2009). [4]

Publicly, DeMuth’s case raised many of the same questions as Laud Humphreys’ work 40 years earlier. What do social scientists owe the public? By protecting his research subjects, is Mr. DeMuth harming those whose labs were vandalized? Is he harming the taxpayers who funded those labs, or is it more important that he emphasize the promise of confidentiality to his research participants? DeMuth’s case also sparked controversy among academics, some of whom thought that as an academic himself, DeMuth should have been more sympathetic to the plight of the faculty and students who lost years of research as a result of the attack on their labs. Many others stood by DeMuth, arguing that the personal and academic freedom of scholars must be protected whether we support their research topics and subjects or not. DeMuth’s academic adviser even created a new group, Scholars for Academic Justice (http://sajumn.wordpress.com), to support DeMuth and other academics who face persecution or prosecution as a result of the research they conduct. What do you think? Should DeMuth have revealed the identities of his research subjects? Why or why not?

Disciplinary considerations

Often times, specific disciplines will provide their own set of guidelines for protecting research subjects and, more generally, for conducting ethical research. For social workers, the National Association of Social Workers (NASW) Code of Ethics section 5.02 describes the responsibilities of social workers in conducting research. Summarized below, these guidelines outline that as a representative of the social work profession, it is your responsibility to conduct to conduct and use research in an ethical manner.

A social worker should:

- Monitor and evaluate policies, programs, and practice interventions

- Contribute to the development of knowledge through research

- Keep current with the best available research evidence to inform practice

- Ensure voluntary and fully informed consent of all participants

- Avoid engaging in any deception in the research process

- Allow participants to withdraw from the study at any time

- Provide access for participants to appropriate supportive services

- Protect research participants from harm

- Maintain confidentiality

- Report findings accurately

- Disclose any conflicts of interest

Key Takeaways

- Researchers must obtain the informed consent of the people who participate in their research.

- Social workers must take steps to minimize the harms that could arise during the research process.

- If a researcher promises anonymity, they cannot link individual participants with their data.

- If a researcher promises confidentiality, they promise not to reveal the identities of research participants, even though they can link individual participants with their data.

- The NASW Code of Ethics includes specific responsibilities for social work researchers.

Glossary

Anonymity- the identity of research participants is not known to researchers

Confidentiality- identifying information about research participants is known to the researchers but is not divulged to anyone else

Informed consent- a research subject’s voluntary agreement to participate in a study based on a full understanding of the study and of the possible risks and benefits involved

Used in qualitative research which involves small groups of people who participate together in interviews focused on a particular topic or issue.

Researchers start with the data and develop a theory or an interpretation that is “grounded in” those data.

Research that combines both quantitative and qualitative approaches.

A detailed description of the research—that is reviewed by an independent committee.