50 Other Presentation Formats

Learning Objectives

- List several ways that researchers in psychology can present their research and the situations in which they might use them.

- Describe how final manuscripts differ from copy manuscripts in American Psychological Association (APA) style.

- Describe the purpose of talks and posters at professional conferences.

- Prepare a short conference-style talk and simple poster presentation.

Writing an empirical research report in American Psychological Association (APA) style is only one way to present new research in psychology. In this section, we look at several other important ways.

Other Types of Manuscripts

The previous section focused on writing empirical research reports to be submitted for publication in a professional journal. However, there are other kinds of manuscripts that are written in APA style, many of which will not be submitted for publication elsewhere. Here we look at a few of them.

Review and Theoretical Articles

Recall that review articles summarize research on a particular topic without presenting new empirical results. When these articles present a new theory, they are often called theoretical articles. Review and theoretical articles are structured much like empirical research reports, with a title page, an abstract, references, appendixes, tables, and figures, and they are written in the same high-level and low-level style. Because they do not report the results of new empirical research, however, there is no method or results section. Of course, the body of the manuscript should still have a logical organization and include an opening that identifies the topic and explains its importance, a literature review that organizes previous research (identifying important relationships among concepts or gaps in the literature), and a closing or conclusion that summarizes the main conclusions and suggests directions for further research or discusses theoretical and practical implications. In a theoretical article, of course, much of the body of the manuscript is devoted to presenting the new theory. Theoretical and review articles are usually divided into sections, each with a heading that is appropriate to that section. The sections and headings can vary considerably from article to article (unlike in an empirical research report). But whatever they are, they should help organize the manuscript and make the argument clear.

Final Manuscripts

Until now, we have focused on the formatting of manuscripts that will be submitted to a professional journal for publication. In contrast, other types of manuscripts are prepared by the author in their final form with no intention of submitting them for publication elsewhere. These are called final manuscripts and include dissertations, theses, and other student papers. These manuscripts may look different from strictly APA style manuscripts in ways that make them easier to read, such as putting tables and figures close to where they are discussed so that the reader does not have to flip to the back of the manuscript to see them. If you read a dissertation or thesis, for example, you might notice it does not adhere strictly to APA style formatting. For student papers, it is important to check with the course instructor about formatting specifics. In a research methods course, papers are usually required to be written as though they were manuscripts being submitted for publication.

Conference Presentations

One of the ways that researchers in psychology share their research with each other is by presenting it at professional conferences. (Although some professional conferences in psychology are devoted mainly to issues of clinical practice, we are concerned here with those that focus on research.) Professional conferences can range from small-scale events involving a dozen researchers who get together for an afternoon to large-scale events involving thousands of researchers who meet for several days. Although researchers attending a professional conference are likely to discuss their work with each other informally, there are two more formal types of presentation: oral presentations (“talks”) and posters. Presenting a talk or poster at a conference usually requires submitting an abstract of the research to the conference organizers in advance and having it accepted for presentation—although the peer review process is typically not as rigorous as it is for manuscripts submitted to a professional journal.

Oral Presentations

In an oral presentation, or “talk,” the presenter stands in front of an audience of other researchers and tells them about their research—usually with the help of a slide show. Talks usually last from 10 to 20 minutes, with the last few minutes reserved for questions from the audience. At larger conferences, talks are typically grouped into sessions lasting an hour or two in which all the talks are on the same general topic.

In preparing a talk, presenters should keep several general principles in mind. The first is that the number of slides should be no more than about one per minute of the talk. The second is that talks are generally structured like an APA-style research report. There is a slide with the title and authors, a few slides to help provide the background, a few more to help describe the method, a few for the results, and a few for the conclusions. The third is that the presenter should look at the audience members and speak to them in a conversational tone that is less formal than APA-style writing but more formal than a conversation with a friend. The slides should not be the focus of the presentation; they should act as visual aids. As such, they should present the main points in bulleted lists or simple tables and figures.

Posters

Another way to present research at a conference is in the form of a poster. A poster is typically presented during a one- to two-hour poster session that takes place in a large room at the conference site. Presenters set up their posters on bulletin boards arranged around the room and stand near them. Other researchers then circulate through the room, read the posters, and talk to the presenters. In essence, poster sessions are a grown-up version of the school science fair. But there is nothing childish about them. Posters are used by professional researchers in all scientific disciplines and they are becoming increasingly common. At a recent American Psychological Association Conference, nearly 2,000 posters were presented across 16 separate poster sessions. Among the reasons posters are so popular is that they encourage meaningful interaction among researchers.

Posters are typically a large size, maybe four feet wide and three feet high. The poster’s information is organized into distinct sections, including a title, author names and affiliations, an introduction, a method section, a results section, a discussion or conclusions section, references, and acknowledgments. Although posters can include an abstract, this may not be necessary because the poster itself is already a brief summary of the research. Figure 11.6 shows two different ways that the information on a poster might be organized.

Given the conditions under which posters are often presented—for example, in crowded ballrooms where people are also eating, drinking, and socializing—they should be constructed so that they present the main ideas behind the research in as simple and clear a way as possible. The font sizes on a poster should be large—perhaps 72 points for the title and authors’ names and 28 points for the main text. The information should be organized into sections with clear headings, and text should be blocked into sentences or bulleted points rather than paragraphs. It is also better for it to be organized in columns and flow from top to bottom rather than to be organized in rows that flow across the poster. This makes it easier for multiple people to read at the same time without bumping into each other. Posters often include elements that add visual interest. Figures can be more colorful than those in an APA-style manuscript. Posters can also include copies of visual stimuli, photographs of the apparatus, or a simulation of participants being tested. They can also include purely decorative elements, although it is best not to overdo these.

Again, a primary reason that posters are becoming such a popular way to present research is that they facilitate interaction among researchers. Many presenters immediately offer to describe their research to visitors and use the poster as a visual aid. At the very least, it is important for presenters to stand by their posters, greet visitors, offer to answer questions, and be prepared for questions and even the occasional critical comment. It is generally a good idea to have a more detailed write-up of the research available for visitors who want more information, to offer to send them a detailed write-up, or to provide contact information so that they can request more information later.

For more information on preparing and presenting both talks and posters, see the website of the Undergraduate Advising and Research Office at Dartmouth College: http://www.dartmouth.edu/~ugar/undergrad/posterinstructions.html

Professional Conferences

Following are links to the websites for several large national conferences in North America and also for several conferences that feature the work of undergraduate students. For a comprehensive list of psychology conferences worldwide, see the following website.

http://www.conferencealerts.com/psychology.htm

Large Conferences

Canadian Psychological Association Convention: http://www.cpa.ca/convention

American Psychological Association Convention: http://www.apa.org/convention

Association for Psychological Science Conference: http://www.psychologicalscience.org/index.php/convention

Canadian Society for Brain, Behavior, and Cognitive Science Annual Meeting: https://www.csbbcs.org/meetings

Society for Personality and Social Psychology Conference: http://meeting.spsp.org/

Psychonomic Society Annual Meeting: http://www.psychonomic.org/annual-meeting

U.S. Regional conferences where undergraduate researchers frequently present

Eastern Psychological Association (EPA): http://www.easternpsychological.org

Midwestern Psychological Association (MPA): http://www.midwesternpsych.org/

New England Psychological Association (NEPA): http://www.newenglandpsychological.org/

Rocky Mountain Psychological Association (RMPA): http://www.rockymountainpsych.com/

Southeastern Psychological Association (SEPA): http://www.sepaonline.com/

Southwestern Psychological Association (SWPA): http://www.swpsych.org/

Western Psychological Association (WPA): http://westernpsych.org/

Canadian Undergraduate Conferences

Connecting Minds Undergraduate Research Conference: http://www.connectingminds.ca

Science Atlantic Psychology Conference: https://scienceatlantic.ca/conferences/

Learning Objectives

- Explain what quasi-experimental research is and distinguish it clearly from both experimental and correlational research.

- Describe three different types of one-group quasi-experimental designs.

- Identify the threats to internal validity associated with each of these designs.

One-Group Posttest Only Design

In a one-group posttest only design, a treatment is implemented (or an independent variable is manipulated) and then a dependent variable is measured once after the treatment is implemented. Imagine, for example, a researcher who is interested in the effectiveness of an anti-drug education program on elementary school students’ attitudes toward illegal drugs. The researcher could implement the anti-drug program, and then immediately after the program ends, the researcher could measure students' attitudes toward illegal drugs.

This is the weakest type of quasi-experimental design. A major limitation to this design is the lack of a control or comparison group. There is no way to determine what the attitudes of these students would have been if they hadn’t completed the anti-drug program. Despite this major limitation, results from this design are frequently reported in the media and are often misinterpreted by the general population. For instance, advertisers might claim that 80% of women noticed their skin looked bright after using Brand X cleanser for a month. If there is no comparison group, then this statistic means little to nothing.

One-Group Pretest-Posttest Design

In a one-group pretest-posttest design, the dependent variable is measured once before the treatment is implemented and once after it is implemented. Let's return to the example of a researcher who is interested in the effectiveness of an anti-drug education program on elementary school students’ attitudes toward illegal drugs. The researcher could measure the attitudes of students at a particular elementary school during one week, implement the anti-drug program during the next week, and finally, measure their attitudes again the following week. The pretest-posttest design is much like a within-subjects experiment in which each participant is tested first under the control condition and then under the treatment condition. It is unlike a within-subjects experiment, however, in that the order of conditions is not counterbalanced because it typically is not possible for a participant to be tested in the treatment condition first and then in an “untreated” control condition.

If the average posttest score is better than the average pretest score (e.g., attitudes toward illegal drugs are more negative after the anti-drug educational program), then it makes sense to conclude that the treatment might be responsible for the improvement. Unfortunately, one often cannot conclude this with a high degree of certainty because there may be other explanations for why the posttest scores may have changed. These alternative explanations pose threats to internal validity.

One alternative explanation goes under the name of history. Other things might have happened between the pretest and the posttest that caused a change from pretest to posttest. Perhaps an anti-drug program aired on television and many of the students watched it, or perhaps a celebrity died of a drug overdose and many of the students heard about it.

Another alternative explanation goes under the name of maturation. Participants might have changed between the pretest and the posttest in ways that they were going to anyway because they are growing and learning. If it were a year long anti-drug program, participants might become less impulsive or better reasoners and this might be responsible for the change in their attitudes toward illegal drugs.

Another threat to the internal validity of one-group pretest-posttest designs is testing, which refers to when the act of measuring the dependent variable during the pretest affects participants' responses at posttest. For instance, completing the measure of attitudes towards illegal drugs may have had an effect on those attitudes. Simply completing this measure may have inspired further thinking and conversations about illegal drugs that then produced a change in posttest scores.

Similarly, instrumentation can be a threat to the internal validity of studies using this design. Instrumentation refers to when the basic characteristics of the measuring instrument change over time. When human observers are used to measure behavior, they may over time gain skill, become fatigued, or change the standards on which observations are based. So participants may have taken the measure of attitudes toward illegal drugs very seriously during the pretest when it was novel but then they may have become bored with the measure at posttest and been less careful in considering their responses.

Another alternative explanation for a change in the dependent variable in a pretest-posttest design is regression to the mean. This refers to the statistical fact that an individual who scores extremely high or extremely low on a variable on one occasion will tend to score less extremely on the next occasion. For example, a bowler with a long-term average of 150 who suddenly bowls a 220 will almost certainly score lower in the next game. Her score will “regress” toward her mean score of 150. Regression to the mean can be a problem when participants are selected for further study because of their extreme scores. Imagine, for example, that only students who scored especially high on the test of attitudes toward illegal drugs (those with extremely favorable attitudes toward drugs) were given the anti-drug program and then were retested. Regression to the mean all but guarantees that their scores will be lower at the posttest even if the training program has no effect.

A closely related concept—and an extremely important one in psychological research—is spontaneous remission. This is the tendency for many medical and psychological problems to improve over time without any form of treatment. The common cold is a good example. If one were to measure symptom severity in 100 common cold sufferers today, give them a bowl of chicken soup every day, and then measure their symptom severity again in a week, they would probably be much improved. This does not mean that the chicken soup was responsible for the improvement, however, because they would have been much improved without any treatment at all. The same is true of many psychological problems. A group of severely depressed people today is likely to be less depressed on average in 6 months. In reviewing the results of several studies of treatments for depression, researchers Michael Posternak and Ivan Miller found that participants in waitlist control conditions improved an average of 10 to 15% before they received any treatment at all (Posternak & Miller, 2001)[1]. Thus one must generally be very cautious about inferring causality from pretest-posttest designs.

A common approach to ruling out the threats to internal validity described above is by revisiting the research design to include a control group, one that does not receive the treatment effect. A control group would be subject to the same threats from history, maturation, testing, instrumentation, regression to the mean, and spontaneous remission and so would allow the researcher to measure the actual effect of the treatment (if any). Of course, including a control group would mean that this is no longer a one-group design.

Does Psychotherapy Work?

Early studies on the effectiveness of psychotherapy tended to use pretest-posttest designs. In a classic 1952 article, researcher Hans Eysenck summarized the results of 24 such studies showing that about two thirds of patients improved between the pretest and the posttest (Eysenck, 1952)[2]. But Eysenck also compared these results with archival data from state hospital and insurance company records showing that similar patients recovered at about the same rate without receiving psychotherapy. This parallel suggested to Eysenck that the improvement that patients showed in the pretest-posttest studies might be no more than spontaneous remission. Note that Eysenck did not conclude that psychotherapy was ineffective. He merely concluded that there was no evidence that it was, and he wrote of “the necessity of properly planned and executed experimental studies into this important field” (p. 323). You can read the entire article here:

http://psychclassics.yorku.ca/Eysenck/psychotherapy.htm

Fortunately, many other researchers took up Eysenck’s challenge, and by 1980 hundreds of experiments had been conducted in which participants were randomly assigned to treatment and control conditions, and the results were summarized in a classic book by Mary Lee Smith, Gene Glass, and Thomas Miller (Smith, Glass, & Miller, 1980)[3]. They found that overall psychotherapy was quite effective, with about 80% of treatment participants improving more than the average control participant. Subsequent research has focused more on the conditions under which different types of psychotherapy are more or less effective.

Interrupted Time Series Design

A variant of the pretest-posttest design is the interrupted time-series design. A time series is a set of measurements taken at intervals over a period of time. For example, a manufacturing company might measure its workers’ productivity each week for a year. In an interrupted time series-design, a time series like this one is “interrupted” by a treatment. In one classic example, the treatment was the reduction of the work shifts in a factory from 10 hours to 8 hours (Cook & Campbell, 1979)[4]. Because productivity increased rather quickly after the shortening of the work shifts, and because it remained elevated for many months afterward, the researcher concluded that the shortening of the shifts caused the increase in productivity. Notice that the interrupted time-series design is like a pretest-posttest design in that it includes measurements of the dependent variable both before and after the treatment. It is unlike the pretest-posttest design, however, in that it includes multiple pretest and posttest measurements.

Figure 8.1 shows data from a hypothetical interrupted time-series study. The dependent variable is the number of student absences per week in a research methods course. The treatment is that the instructor begins publicly taking attendance each day so that students know that the instructor is aware of who is present and who is absent. The top panel of Figure 8.1 shows how the data might look if this treatment worked. There is a consistently high number of absences before the treatment, and there is an immediate and sustained drop in absences after the treatment. The bottom panel of Figure 8.1 shows how the data might look if this treatment did not work. On average, the number of absences after the treatment is about the same as the number before. This figure also illustrates an advantage of the interrupted time-series design over a simpler pretest-posttest design. If there had been only one measurement of absences before the treatment at Week 7 and one afterward at Week 8, then it would have looked as though the treatment were responsible for the reduction. The multiple measurements both before and after the treatment suggest that the reduction between Weeks 7 and 8 is nothing more than normal week-to-week variation.

Learning Objectives

- Describe the inductive approach to research, and provide examples of inductive research

- Describe the deductive approach to research, and provide examples of deductive research

- Describe the ways that inductive and deductive approaches may be complementary

Theory structures and informs social work research. Conversely, social work research structures and informs theory. Students become aware of the reciprocal relationship between theory and research when they consider the relationships between the two in inductive and deductive approaches. In both cases, theory is crucial but the relationship between theory and research differs for each approach.

Inductive and deductive approaches to research are quite different, but they can also be complementary. Let’s start by looking at each one and how they differ from one another. Then we’ll move on to thinking about how they complement one another.

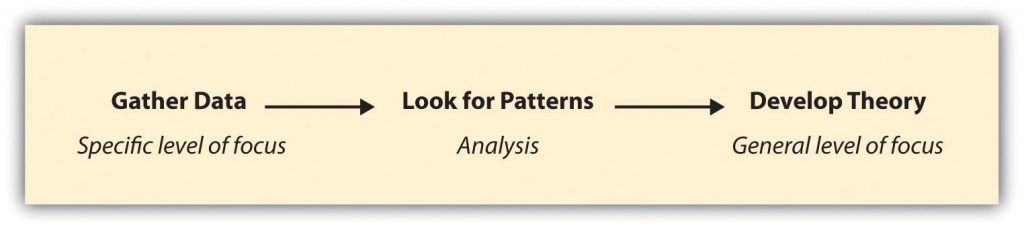

Inductive approaches and some examples

When a researcher utilizes an inductive approach, they begin by collecting data that is relevant to their topic of interest. Once a substantial amount of data have been collected, the researcher will take a break from data collection to step back and get a bird’s eye view of their data. At this stage, the researcher looks for patterns in the data, working to develop a theory that could explain those patterns. Thus, when researchers take an inductive approach, they start with a set of observations and then they move from those particular experiences to a more general set of propositions about those experiences. In other words, they move from data to theory, or from the specific to the general. Figure 6.1 outlines the steps involved with an inductive approach to research.

There are many good examples of inductive research, but we’ll look at just a few here. One fascinating study in which the researchers took an inductive approach is Katherine Allen, Christine Kaestle, and Abbie Goldberg’s (2011) study [5] of how boys and young men learn about menstruation. To understand this process, Allen and her colleagues analyzed the written narratives of 23 young men in which the men described how they learned about menstruation, what they thought of it when they first learned about it, and what they think of it now. By looking for patterns across all 23 men’s narratives, the researchers were able to develop a general theory of how boys and young men learn about this aspect of girls’ and women’s biology. They conclude that sisters play an important role in boys’ early understanding of menstruation, that menstruation makes boys feel somewhat separated from girls, and that as they enter young adulthood and form romantic relationships, young men develop more mature attitudes about menstruation. Note how this study began with the data—men’s narratives of learning about menstruation—and tried to develop a theory.

In another inductive study, Kristin Ferguson and colleagues (Ferguson, Kim, & McCoy, 2011) [6] analyzed empirical data to better understand how best to meet the needs of young people who are experiencing homelessness. The authors analyzed data from focus groups with 20 young people at a homeless shelter. From these data they developed a set of recommendations for those interested in applied interventions that serve youth that are experiencing homelessness. The researchers also developed hypotheses for people who might wish to conduct further investigation of the topic. Though Ferguson and her colleagues did not test the hypotheses that they developed from their analysis, their study ends where most deductive investigations begin: with a theory and a hypothesis derived from that theory.

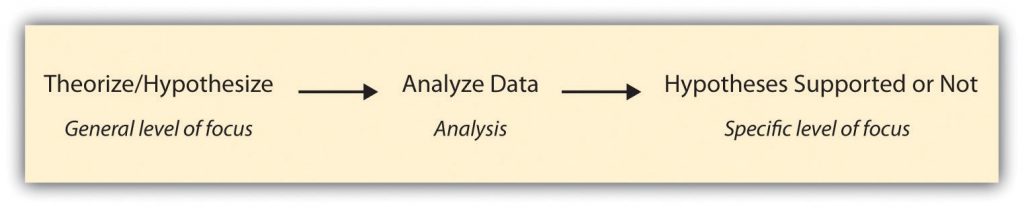

Deductive approaches and some examples

Researchers taking a deductive approach will start with a compelling social theory and then test its implications with data. In other words, they utilize the same steps as inductive research, but they will reverse the order, moving from general to more specific levels. Deductive research approach is most associated with scientific investigation. The researcher studies what others have done, reads existing theories of whatever phenomenon they are studying, and then tests hypotheses that emerge from those theories. Figure 6.2 outlines the steps involved with a deductive approach to research.

Although not all social science researchers utilize a deductive approach, there are some excellent, recent examples of deductive research. We’ll take a look at a couple of those next.

In a study of US law enforcement responses to hate crimes, Ryan King and colleagues (King, Messner, & Baller, 2009) [7] hypothesized that law enforcement’s response would be less vigorous in areas of the country that had a stronger history of racial violence. The authors developed their hypothesis from their reading of prior research and theories on the topic. They tested the hypothesis by analyzing data on states’ lynching histories and hate crime responses. Overall, the authors found support for their hypothesis. One might associate this research with critical theory.

In another recent deductive study, Melissa Milkie and Catharine Warner (2011) [8] studied the effects of different classroom environments on first graders’ mental health. Based on prior research and theory, Milkie and Warner hypothesized that negative classroom features, such as a lack of basic supplies and even heat, would be associated with emotional and behavioral problems in children. One might associate this research with systems theory. The researchers found support for their hypothesis, demonstrating that policymakers should be more attentive to the mental health outcomes of children’s school experiences, just as they track academic outcomes (American Sociological Association, 2011). [9]

Complementary approaches

While inductive and deductive approaches to research seem quite different, they can be rather complementary. In some cases, researchers will plan for their study to include multiple components, one inductive and the other deductive. In other cases, a researcher might begin their study planning to utilize only one approach but then discover along the way that the other approach is needed to help illuminate findings. Here is an example of each such case.

The original author of the textbook from which this textbook is adapted, Dr. Amy Blackstone, relates a story about her collaborative research on sexual harassment.

We began the study knowing that we would like to take both a deductive and an inductive approach in our work. We therefore administered a quantitative survey, the responses to which we could analyze in order to test hypotheses, and also conducted qualitative interviews with a number of the survey participants. The survey data were well suited to a deductive approach; we could analyze those data to test hypotheses that were generated based on theories of harassment. The interview data were well suited to an inductive approach; we looked for patterns across the interviews and then tried to make sense of those patterns by theorizing about them.

For one paper (Uggen & Blackstone, 2004), [10] we began with a prominent feminist theory of the sexual harassment of adult women and developed a set of hypotheses outlining how we expected the theory to apply in the case of younger women’s and men’s harassment experiences. We then tested our hypotheses by analyzing the survey data. In general, we found support for the theory that posited that the current gender system, in which heteronormative men wield the most power in the workplace, explained workplace sexual harassment—not just of adult women but of younger women and men as well. In a more recent paper (Blackstone, Houle, & Uggen, 2006), [11] we did not hypothesize about what we might find but instead inductively analyzed interview data, looking for patterns that might tell us something about how or whether workers’ perceptions of harassment change as they age and gain workplace experience. From this analysis, we determined that workers’ perceptions of harassment did indeed shift as they gained experience and that their later definitions of harassment were more stringent than those they held during adolescence. Overall, our desire to understand young workers’ harassment experiences fully—in terms of their objective workplace experiences, their perceptions of those experiences, and their stories of their experiences—led us to adopt both deductive and inductive approaches in the work. (Blackstone, n.d., p. 21)

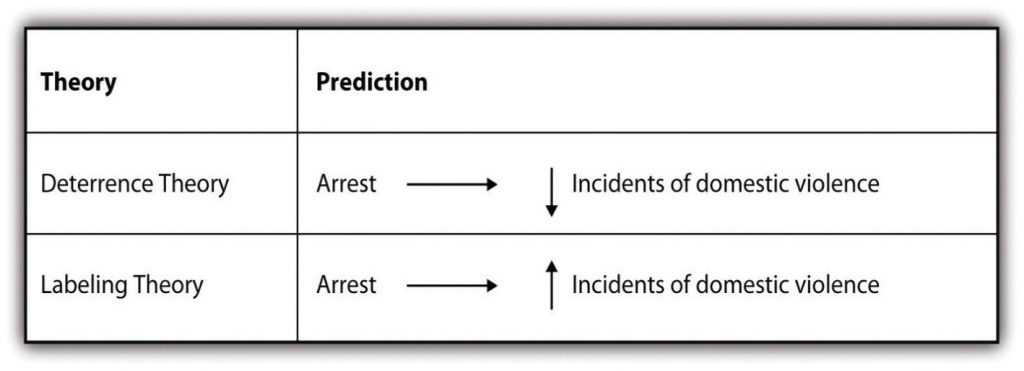

Researchers may not set out to employ both approaches in their work, but sometimes their use of one approach leads them to the other. One such example is described eloquently in Russell Schutt’s Investigating the Social World (2006). [12] As Schutt describes, researchers Lawrence Sherman and Richard Berk (1984) [13] conducted an experiment to test two competing theories of the effects of punishment on deterring deviance (in this case, domestic violence). Specifically, Sherman and Berk hypothesized that deterrence theory would provide a better explanation of the effects of arresting accused batterers than labeling theory. Deterrence theory predicts that arresting an accused spouse batterer will reduce future incidents of violence. Conversely, labeling theory predicts that arresting accused spouse batterers will increase future incidents. Figure 6.3 summarizes the two competing theories and the predictions that Sherman and Berk set out to test.

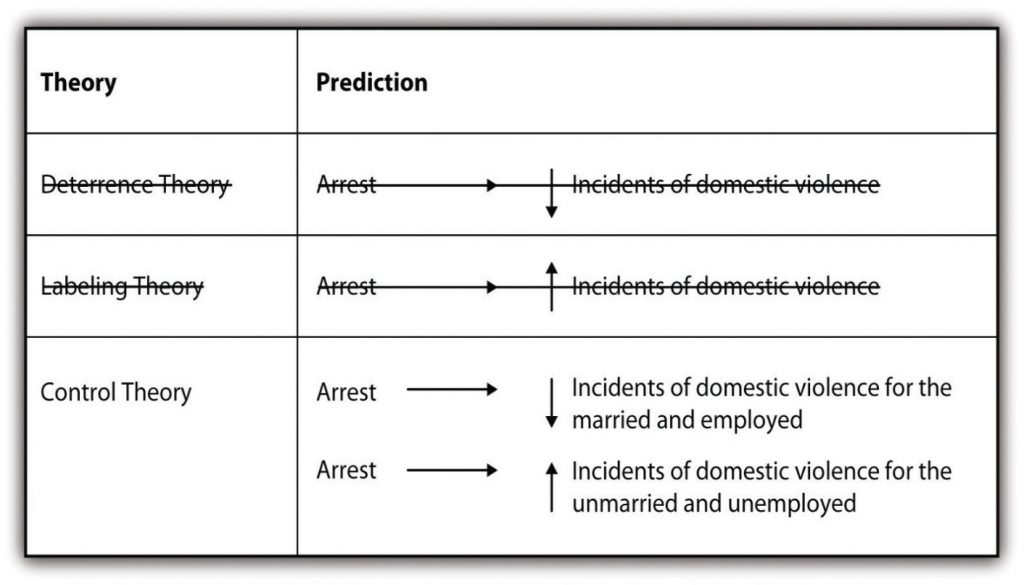

After conducting an experiment with the help of local police, Sherman and Berk found, that arrest did deter future incidents of violence, thus supporting their hypothesis that deterrence theory would better predict the effect of arrest. After conducting this research, they and other researchers went on to conduct similar experiments [14] in six additional cities (Berk, Campbell, Klap, & Western, 1992; Pate & Hamilton, 1992; Sherman & Smith, 1992). [15] The follow-up studies yielded mixed results. In some cases, arrest deterred future incidents of violence while in other cases, arrest did not. These results left the researchers with new data that they needed to explain, so they utilized an inductive approach to make sense of their latest empirical observations. The new studies revealed that arrest has a deterrent effect on individuals that are married and employed, while arrest may encourage future battering offenses in individuals that are unmarried and unemployed. Researchers thus turned to control theory to explain their observations, as it predicts that stakes in conformity are developed through social ties like marriage and employment.

Sherman and Berk's research and the associated follow-up studies demonstrate that researchers can start with a deductive approach and move to inductive approach when confronted with new data that must be explained.

Key Takeaways

- The inductive approach begins with a set of empirical observations, seeking patterns in those observations, and then theorizing about those patterns.

- The deductive approach begins with a theory, developing hypotheses from that theory, and then collecting and analyzing data to test those hypotheses.

- Inductive and deductive approaches to research can be employed together for a more complete understanding of the topic that a researcher is studying.

- Though researchers don’t always set out to use both inductive and deductive strategies in their work, they sometimes find that new questions arise in the course of an investigation that can best be answered by employing both approaches.

Glossary

Deductive approach- when a researcher studies what others have done, reads existing theories of whatever phenomenon they are studying, and then tests hypotheses that emerge from those theories

Inductive approach- when a researcher starts with a set of observations and then moves from particular experiences to a more general set of propositions about those experiences

Learning Objectives

- Explain what internal validity is and why experiments are considered to be high in internal validity.

- Explain what external validity is and evaluate studies in terms of their external validity.

- Explain the concepts of construct and statistical validity.

Four Big Validities

When we read about psychology experiments with a critical view, one question to ask is “is this study valid (accurate)?” However, that question is not as straightforward as it seems because, in psychology, there are many different kinds of validities. Researchers have focused on four validities to help assess whether an experiment is sound (Judd & Kenny, 1981; Morling, 2014)[17][18]: internal validity, external validity, construct validity, and statistical validity. We will explore each validity in depth.

Internal Validity

Two variables being statistically related does not necessarily mean that one causes the other. In your psychology education, you have probably heard the term, “Correlation does not imply causation.” For example, if it were the case that people who exercise regularly are happier than people who do not exercise regularly, this implication would not necessarily mean that exercising increases people’s happiness. It could mean instead that greater happiness causes people to exercise or that something like better physical health causes people to exercise and be happier.

The purpose of an experiment, however, is to show that two variables are statistically related and to do so in a way that supports the conclusion that the independent variable caused any observed differences in the dependent variable. The logic is based on this assumption: If the researcher creates two or more highly similar conditions and then manipulates the independent variable to produce just one difference between them, then any later difference between the conditions must have been caused by the independent variable. For example, because the only difference between Darley and Latané’s conditions was the number of students that participants believed to be involved in the discussion, this difference in belief must have been responsible for differences in helping between the conditions.

An empirical study is said to be high in internal validity if the way it was conducted supports the conclusion that the independent variable caused any observed differences in the dependent variable. Thus experiments are high in internal validity because the way they are conducted—with the manipulation of the independent variable and the control of extraneous variables (such as through the use of random assignment to minimize confounds)—provides strong support for causal conclusions. In contrast, non-experimental research designs (e.g., correlational designs), in which variables are measured but are not manipulated by an experimenter, are low in internal validity.

External Validity

At the same time, the way that experiments are conducted sometimes leads to a different kind of criticism. Specifically, the need to manipulate the independent variable and control extraneous variables means that experiments are often conducted under conditions that seem artificial (Bauman, McGraw, Bartels, & Warren, 2014)[19]. In many psychology experiments, the participants are all undergraduate students and come to a classroom or laboratory to fill out a series of paper-and-pencil questionnaires or to perform a carefully designed computerized task. Consider, for example, an experiment in which researcher Barbara Fredrickson and her colleagues had undergraduate students come to a laboratory on campus and complete a math test while wearing a swimsuit (Fredrickson, Roberts, Noll, Quinn, & Twenge, 1998)[20]. At first, this manipulation might seem silly. When will undergraduate students ever have to complete math tests in their swimsuits outside of this experiment?

The issue we are confronting is that of external validity. An empirical study is high in external validity if the way it was conducted supports generalizing the results to people and situations beyond those actually studied. As a general rule, studies are higher in external validity when the participants and the situation studied are similar to those that the researchers want to generalize to and participants encounter every day, often described as mundane realism. Imagine, for example, that a group of researchers is interested in how shoppers in large grocery stores are affected by whether breakfast cereal is packaged in yellow or purple boxes. Their study would be high in external validity and have high mundane realism if they studied the decisions of ordinary people doing their weekly shopping in a real grocery store. If the shoppers bought much more cereal in purple boxes, the researchers would be fairly confident that this increase would be true for other shoppers in other stores. Their study would be relatively low in external validity, however, if they studied a sample of undergraduate students in a laboratory at a selective university who merely judged the appeal of various colors presented on a computer screen; however, this study would have high psychological realism where the same mental process is used in both the laboratory and in the real world. If the students judged purple to be more appealing than yellow, the researchers would not be very confident that this preference is relevant to grocery shoppers’ cereal-buying decisions because of low external validity but they could be confident that the visual processing of colors has high psychological realism.

We should be careful, however, not to draw the blanket conclusion that experiments are low in external validity. One reason is that experiments need not seem artificial. Consider that Darley and Latané’s experiment provided a reasonably good simulation of a real emergency situation. Or consider field experiments that are conducted entirely outside the laboratory. In one such experiment, Robert Cialdini and his colleagues studied whether hotel guests choose to reuse their towels for a second day as opposed to having them washed as a way of conserving water and energy (Cialdini, 2005)[21]. These researchers manipulated the message on a card left in a large sample of hotel rooms. One version of the message emphasized showing respect for the environment, another emphasized that the hotel would donate a portion of their savings to an environmental cause, and a third emphasized that most hotel guests choose to reuse their towels. The result was that guests who received the message that most hotel guests choose to reuse their towels, reused their own towels substantially more often than guests receiving either of the other two messages. Given the way they conducted their study, it seems very likely that their result would hold true for other guests in other hotels.

A second reason not to draw the blanket conclusion that experiments are low in external validity is that they are often conducted to learn about psychological processes that are likely to operate in a variety of people and situations. Let us return to the experiment by Fredrickson and colleagues. They found that the women in their study, but not the men, performed worse on the math test when they were wearing swimsuits. They argued that this gender difference was due to women’s greater tendency to objectify themselves—to think about themselves from the perspective of an outside observer—which diverts their attention away from other tasks. They argued, furthermore, that this process of self-objectification and its effect on attention is likely to operate in a variety of women and situations—even if none of them ever finds herself taking a math test in her swimsuit.

Construct Validity

In addition to the generalizability of the results of an experiment, another element to scrutinize in a study is the quality of the experiment’s manipulations or the construct validity. The research question that Darley and Latané started with is “does helping behavior become diffused?” They hypothesized that participants in a lab would be less likely to help when they believed there were more potential helpers besides themselves. This conversion from research question to experiment design is called operationalization (see Chapter 4 for more information about the operational definition). Darley and Latané operationalized the independent variable of diffusion of responsibility by increasing the number of potential helpers. In evaluating this design, we would say that the construct validity was very high because the experiment’s manipulations very clearly speak to the research question; there was a crisis, a way for the participant to help, and increasing the number of other students involved in the discussion, they provided a way to test diffusion.

What if the number of conditions in Darley and Latané’s study changed? Consider if there were only two conditions: one student involved in the discussion or two. Even though we may see a decrease in helping by adding another person, it may not be a clear demonstration of diffusion of responsibility, just merely the presence of others. We might think it was a form of Bandura’s concept of social inhibition. The construct validity would be lower. However, had there been five conditions, perhaps we would see the decrease continue with more people in the discussion or perhaps it would plateau after a certain number of people. In that situation, we may develop a more nuanced understanding of the phenomenon. But by adding still more conditions, the construct validity may not get higher. When designing your own experiment, consider how well the research question is operationalized your study.

Statistical Validity

Statistical validity concerns the proper statistical treatment of data and the soundness of the researchers’ statistical conclusions. There are many different types of inferential statistics tests (e.g., t-tests, ANOVA, regression, correlation) and statistical validity concerns the use of the proper type of test to analyze the data. When considering the proper type of test, researchers must consider the scale of measure their dependent variable was measured on and the design of their study. Further, many inferential statistics tests carry certain assumptions (e.g., the data are normally distributed) and statistical validity is threatened when these assumptions are not met but the statistics are used nonetheless.

One common critique of experiments is that a study did not have enough participants. The main reason for this criticism is that it is difficult to generalize about a population from a small sample. At the outset, it seems as though this critique is about external validity but there are studies where small sample sizes are not a problem (subsequent chapters will discuss how small samples, even of only one person, are still very illuminating for psychological research). Therefore, small sample sizes are actually a critique of statistical validity. The statistical validity speaks to whether the statistics conducted in the study are sound and support the conclusions that are made.

The proper statistical analysis should be conducted on the data to determine whether the difference or relationship that was predicted was indeed found. Interestingly, the likelihood of detecting an effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable depends on not just whether a relationship really exists between these variables, but also the number of conditions and the size of the sample. This is why it is important to conduct a power analysis when designing a study, which is a calculation that informs you of the number of participants you need to recruit to detect an effect of a specific size.

Prioritizing Validities

These four big validities--internal, external, construct, and statistical--are useful to keep in mind when both reading about other experiments and designing your own. However, researchers must prioritize and often it is not possible to have high validity in all four areas. In Cialdini’s study on towel usage in hotels, the external validity was high but the statistical validity was more modest. This discrepancy does not invalidate the study but it shows where there may be room for improvement for future follow-up studies (Goldstein, Cialdini, & Griskevicius, 2008)[22]. Morling (2014) points out that many psychology studies have high internal and construct validity but sometimes sacrifice external validity.

When the order in which the items are presented affects people’s responses.