25 Experimentation and Validity

Learning Objectives

- Explain what internal validity is and why experiments are considered to be high in internal validity.

- Explain what external validity is and evaluate studies in terms of their external validity.

- Explain the concepts of construct and statistical validity.

Four Big Validities

When we read about psychology experiments with a critical view, one question to ask is “is this study valid (accurate)?” However, that question is not as straightforward as it seems because, in psychology, there are many different kinds of validities. Researchers have focused on four validities to help assess whether an experiment is sound (Judd & Kenny, 1981; Morling, 2014)[1][2]: internal validity, external validity, construct validity, and statistical validity. We will explore each validity in depth.

Internal Validity

Two variables being statistically related does not necessarily mean that one causes the other. In your psychology education, you have probably heard the term, “Correlation does not imply causation.” For example, if it were the case that people who exercise regularly are happier than people who do not exercise regularly, this implication would not necessarily mean that exercising increases people’s happiness. It could mean instead that greater happiness causes people to exercise or that something like better physical health causes people to exercise and be happier.

The purpose of an experiment, however, is to show that two variables are statistically related and to do so in a way that supports the conclusion that the independent variable caused any observed differences in the dependent variable. The logic is based on this assumption: If the researcher creates two or more highly similar conditions and then manipulates the independent variable to produce just one difference between them, then any later difference between the conditions must have been caused by the independent variable. For example, because the only difference between Darley and Latané’s conditions was the number of students that participants believed to be involved in the discussion, this difference in belief must have been responsible for differences in helping between the conditions.

An empirical study is said to be high in internal validity if the way it was conducted supports the conclusion that the independent variable caused any observed differences in the dependent variable. Thus experiments are high in internal validity because the way they are conducted—with the manipulation of the independent variable and the control of extraneous variables (such as through the use of random assignment to minimize confounds)—provides strong support for causal conclusions. In contrast, non-experimental research designs (e.g., correlational designs), in which variables are measured but are not manipulated by an experimenter, are low in internal validity.

External Validity

At the same time, the way that experiments are conducted sometimes leads to a different kind of criticism. Specifically, the need to manipulate the independent variable and control extraneous variables means that experiments are often conducted under conditions that seem artificial (Bauman, McGraw, Bartels, & Warren, 2014)[3]. In many psychology experiments, the participants are all undergraduate students and come to a classroom or laboratory to fill out a series of paper-and-pencil questionnaires or to perform a carefully designed computerized task. Consider, for example, an experiment in which researcher Barbara Fredrickson and her colleagues had undergraduate students come to a laboratory on campus and complete a math test while wearing a swimsuit (Fredrickson, Roberts, Noll, Quinn, & Twenge, 1998)[4]. At first, this manipulation might seem silly. When will undergraduate students ever have to complete math tests in their swimsuits outside of this experiment?

The issue we are confronting is that of external validity. An empirical study is high in external validity if the way it was conducted supports generalizing the results to people and situations beyond those actually studied. As a general rule, studies are higher in external validity when the participants and the situation studied are similar to those that the researchers want to generalize to and participants encounter every day, often described as mundane realism. Imagine, for example, that a group of researchers is interested in how shoppers in large grocery stores are affected by whether breakfast cereal is packaged in yellow or purple boxes. Their study would be high in external validity and have high mundane realism if they studied the decisions of ordinary people doing their weekly shopping in a real grocery store. If the shoppers bought much more cereal in purple boxes, the researchers would be fairly confident that this increase would be true for other shoppers in other stores. Their study would be relatively low in external validity, however, if they studied a sample of undergraduate students in a laboratory at a selective university who merely judged the appeal of various colors presented on a computer screen; however, this study would have high psychological realism where the same mental process is used in both the laboratory and in the real world. If the students judged purple to be more appealing than yellow, the researchers would not be very confident that this preference is relevant to grocery shoppers’ cereal-buying decisions because of low external validity but they could be confident that the visual processing of colors has high psychological realism.

We should be careful, however, not to draw the blanket conclusion that experiments are low in external validity. One reason is that experiments need not seem artificial. Consider that Darley and Latané’s experiment provided a reasonably good simulation of a real emergency situation. Or consider field experiments that are conducted entirely outside the laboratory. In one such experiment, Robert Cialdini and his colleagues studied whether hotel guests choose to reuse their towels for a second day as opposed to having them washed as a way of conserving water and energy (Cialdini, 2005)[5]. These researchers manipulated the message on a card left in a large sample of hotel rooms. One version of the message emphasized showing respect for the environment, another emphasized that the hotel would donate a portion of their savings to an environmental cause, and a third emphasized that most hotel guests choose to reuse their towels. The result was that guests who received the message that most hotel guests choose to reuse their towels, reused their own towels substantially more often than guests receiving either of the other two messages. Given the way they conducted their study, it seems very likely that their result would hold true for other guests in other hotels.

A second reason not to draw the blanket conclusion that experiments are low in external validity is that they are often conducted to learn about psychological processes that are likely to operate in a variety of people and situations. Let us return to the experiment by Fredrickson and colleagues. They found that the women in their study, but not the men, performed worse on the math test when they were wearing swimsuits. They argued that this gender difference was due to women’s greater tendency to objectify themselves—to think about themselves from the perspective of an outside observer—which diverts their attention away from other tasks. They argued, furthermore, that this process of self-objectification and its effect on attention is likely to operate in a variety of women and situations—even if none of them ever finds herself taking a math test in her swimsuit.

Construct Validity

In addition to the generalizability of the results of an experiment, another element to scrutinize in a study is the quality of the experiment’s manipulations or the construct validity. The research question that Darley and Latané started with is “does helping behavior become diffused?” They hypothesized that participants in a lab would be less likely to help when they believed there were more potential helpers besides themselves. This conversion from research question to experiment design is called operationalization (see Chapter 4 for more information about the operational definition). Darley and Latané operationalized the independent variable of diffusion of responsibility by increasing the number of potential helpers. In evaluating this design, we would say that the construct validity was very high because the experiment’s manipulations very clearly speak to the research question; there was a crisis, a way for the participant to help, and increasing the number of other students involved in the discussion, they provided a way to test diffusion.

What if the number of conditions in Darley and Latané’s study changed? Consider if there were only two conditions: one student involved in the discussion or two. Even though we may see a decrease in helping by adding another person, it may not be a clear demonstration of diffusion of responsibility, just merely the presence of others. We might think it was a form of Bandura’s concept of social inhibition. The construct validity would be lower. However, had there been five conditions, perhaps we would see the decrease continue with more people in the discussion or perhaps it would plateau after a certain number of people. In that situation, we may develop a more nuanced understanding of the phenomenon. But by adding still more conditions, the construct validity may not get higher. When designing your own experiment, consider how well the research question is operationalized your study.

Statistical Validity

Statistical validity concerns the proper statistical treatment of data and the soundness of the researchers’ statistical conclusions. There are many different types of inferential statistics tests (e.g., t-tests, ANOVA, regression, correlation) and statistical validity concerns the use of the proper type of test to analyze the data. When considering the proper type of test, researchers must consider the scale of measure their dependent variable was measured on and the design of their study. Further, many inferential statistics tests carry certain assumptions (e.g., the data are normally distributed) and statistical validity is threatened when these assumptions are not met but the statistics are used nonetheless.

One common critique of experiments is that a study did not have enough participants. The main reason for this criticism is that it is difficult to generalize about a population from a small sample. At the outset, it seems as though this critique is about external validity but there are studies where small sample sizes are not a problem (subsequent chapters will discuss how small samples, even of only one person, are still very illuminating for psychological research). Therefore, small sample sizes are actually a critique of statistical validity. The statistical validity speaks to whether the statistics conducted in the study are sound and support the conclusions that are made.

The proper statistical analysis should be conducted on the data to determine whether the difference or relationship that was predicted was indeed found. Interestingly, the likelihood of detecting an effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable depends on not just whether a relationship really exists between these variables, but also the number of conditions and the size of the sample. This is why it is important to conduct a power analysis when designing a study, which is a calculation that informs you of the number of participants you need to recruit to detect an effect of a specific size.

Prioritizing Validities

These four big validities–internal, external, construct, and statistical–are useful to keep in mind when both reading about other experiments and designing your own. However, researchers must prioritize and often it is not possible to have high validity in all four areas. In Cialdini’s study on towel usage in hotels, the external validity was high but the statistical validity was more modest. This discrepancy does not invalidate the study but it shows where there may be room for improvement for future follow-up studies (Goldstein, Cialdini, & Griskevicius, 2008)[6]. Morling (2014) points out that many psychology studies have high internal and construct validity but sometimes sacrifice external validity.

- Judd, C.M. & Kenny, D.A. (1981). Estimating the effects of social interventions. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press. ↵

- Morling, B. (2014, April). Teach your students to be better consumers. APS Observer. Retrieved from http://www.psychologicalscience.org/index.php/publications/observer/2014/april-14/teach-your-students-to-be-better-consumers.html ↵

- Bauman, C.W., McGraw, A.P., Bartels, D.M., & Warren, C. (2014). Revisiting external validity: Concerns about trolley problems and other sacrificial dilemmas in moral psychology. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 8/9, 536-554. ↵

- Fredrickson, B. L., Roberts, T.-A., Noll, S. M., Quinn, D. M., & Twenge, J. M. (1998). The swimsuit becomes you: Sex differences in self-objectification, restrained eating, and math performance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75, 269–284. ↵

- Cialdini, R. (2005, April). Don’t throw in the towel: Use social influence research. APS Observer. Retrieved from http://www.psychologicalscience.org/index.php/publications/observer/2005/april-05/dont-throw-in-the-towel-use-social-influence-research.html ↵

- Goldstein, N. J., Cialdini, R. B., & Griskevicius, V. (2008). A room with a viewpoint: Using social norms to motivate environmental conservation in hotels. Journal of Consumer Research, 35, 472–482. ↵

Refers to the degree to which we can confidently infer a causal relationship between variables.

Refers to the degree to which we can generalize the findings to other circumstances or settings, like the real-world environment.

When the participants and the situation studied are similar to those that the researchers want to generalize to and participants encounter every day.

Where the same mental process is used in both the laboratory and in the real world.

Learning Objectives

- Describe useful strategies to employ when searching for literature

- Identify how to narrow down search results to the most relevant sources

One of the drawbacks (or joys, depending on your perspective) of being a researcher in the 21st century is that we can do much of our work without ever leaving the comfort of our recliners. This is certainly true of familiarizing yourself with the literature. Most libraries offer incredible online search options and access to important databases of academic journal articles.

A literature search usually follows these steps:

- Building search queries

- Finding the right database

- Skimming the abstracts of articles

- Looking at authors and journal names

- Examining references

- Searching for meta-analyses and systematic reviews

Step 1: Building a search query with keywords

What do you type when you are searching for something on Google? Are you a question-asker? Do you type in full sentences or just a few keywords? What you type into a database or search engine like Google is called a query. Well-constructed queries get you to the information you need faster, while unclear queries will force you to sift through dozens of irrelevant articles before you find the ones you want.

The words you use in your search query will determine the results you get. Unfortunately, different studies often use different words to mean the same thing. A study may describe its topic as substance abuse, rather than addiction. Think of different keywords that are relevant to your topic area and write them down. Often in social work research, there is a bit of jargon to learn in crafting your search queries. For example, if you wanted to learn more about people of low-income households who do not have access to a bank account, it may be helpful to include the jargon term "unbanked" in your search query. If you wanted to learn about children who take on parental roles in families, you may need to include “parentification” as part of your search query. As undergraduate researchers, you are not expected to know these terms ahead of time. Instead, start with the keywords you already know. Once you read more about your topic, start including new keywords that will return the most relevant search results for you.

Google is a “natural language” search engine, which means it tries to use its knowledge of how people to talk to better understand your query. Google’s academic database, Google Scholar, incorporates that same approach. However, other databases that are important for social work research—such as Academic Search Complete, PSYCinfo, and PubMed—will not return useful results if you ask a question, type a sentence, or use a phrase as your search query. Unlike Google Scholar, these databases are best used by typing in keywords. Instead of typing “the effects of cocaine addiction on the quality of parenting,” you might type in “cocaine AND parenting” or “addiction AND child development.” Note: you would not actually use the quotation marks in your search query for these examples.

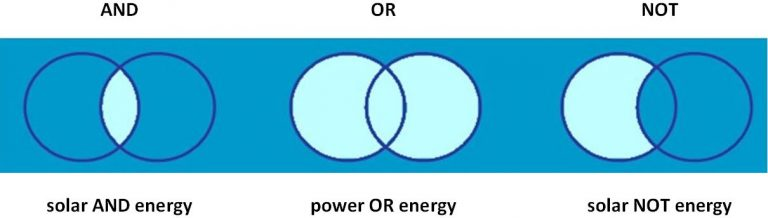

These operators (AND, OR, NOT) are part of what is called Boolean searching. Boolean searching works like a simple computer program. Your search query is made up of words connected by operators. Searching for “cocaine AND parenting” returns articles that mention both cocaine and parenting. There are lots of articles on cocaine and lots of articles on parenting, but fewer articles that discuss both topics together. In this way, the AND operator reduces the number of results you will get from your search query because both terms must be present. The NOT operator also reduces the number of results you get from your query. For example, perhaps you wanted to exclude issues related to pregnancy. Searching for “cocaine AND parenting NOT pregnancy” would exclude articles that mentioned pregnancy from your results. Conversely, the OR operator would increase the number of results you get from your query. For example, searching for “cocaine OR parenting” would return not only articles that mentioned both words but also those that mentioned only one of your two search terms. This relationship is visualized in Figure 2.1 below.

As my students have said in the past, probably the most frustrating part about literature searching is looking at the number of search results for your query. How could anyone be expected to look at hundreds of thousands of articles on a topic? Don’t worry. You don’t have to read all those articles to know enough about your topic area to produce a good research study. A good search query should bring you to at least a few relevant articles to your topic, which is more than enough to get you started. However, an excellent search query can narrow down your results to a much smaller number of articles, all of which are specifically focused on your topic area. Here are some tips for reducing the number of articles in your topic area:

- Use quotation marks to indicate exact phrases, like “mental health” or “substance abuse.”

- Search for your keywords in the ABSTRACT. A lot of your results may be from articles about irrelevant topics simply that mention your search term once. If your topic isn’t in the abstract, chances are the article isn’t relevant. You can be even more restrictive and search for your keywords in the TITLE. Academic databases provide these options in their advanced search tools.

- Use multiple keywords in the same query. Simply adding “addiction” onto a search for “substance abuse” will narrow down your results considerably.

- Use a SUBJECT heading like “substance abuse” to get results from authors who have tagged their articles as addressing the topic of substance abuse. Subject headings are likely to not have all the articles on a topic but are a good place to start.

- Narrow down the years of your search. Unless you are gathering historical information about a topic, you are unlikely to find articles older than 10-15 years to be useful. They are less useful because they no longer tell you the current knowledge on a topic. All databases have options to narrow your results down by year.

- Talk to a librarian. They are professional knowledge-gatherers, and there is often a librarian assigned to your department. Their job is to help you find what you need to know.

Step 2: Finding the right database

The four biggest databases you will probably use for finding academic journal articles relevant to social work are: Google Scholar, Academic Search Complete, PSYCinfo, and PubMed. Each has distinct advantages and disadvantages.

Because Google Scholar is a natural language search engine, you are more likely to get what you want without having to fuss with wording. It can be linked via Library Links to your university login, allowing you to access journal articles with one click on the Google Scholar page. Google Scholar also allows you to save articles in folders and provides a (somewhat correct) APA citation for each article. Google Scholar will automatically display not only journal articles, but also books, government and foundation reports, and gray literature, so you need to make sure that the source you are using is reputable. Look for the advanced search feature to narrow down your results further.

Academic Search Complete is available through your school’s library, usually under page titled databases. It is similar to Google Scholar in its breadth, as it contains a number of smaller databases from a variety of social science disciplines (including Social Work Abstracts). You have to use Boolean searching techniques, and there are a number of advanced search features to further narrow down your results.

PSYCinfo and PubMed focus on specific disciplines. PSYCinfo indexes articles on psychology, and PubMed indexes articles related to medical science. Because these databases are more narrowly targeted, you are more likely to get the specific psychological or medical knowledge you desire. If you were to use a more general search engine like Google Scholar, you may get more irrelevant results. Finally, it is worth mentioning that many university libraries have a meta-search engine which searches all the databases to which they have access.

Step 3: Skimming abstracts and downloading articles

Once you’ve settled on your search query and database, you should start to see articles that might be relevant to your topic. Rather than read every article, skim through the abstract to judge whether this article is relevant to your specific topic. If you like the article, make sure to download the full text PDF to your computer so you can read it later. Part of the tuition and fees your university charges you goes to paying major publishers of academic journals for the privilege of accessing their articles. Because access fees are incredibly costly, your school likely does not pay for access to all the journals in the world. While you are in school, you should never have to pay for access to an academic journal article. Instead, if your school does not subscribe to a journal you need to read, try using inter-library loan to get the article. On your university library’s homepage, there is likely a link to inter-library loan. Just enter the information for your article (e.g. author, publication year, title), and a librarian will work with librarians at other schools to get you the PDF of the article that you need. After you leave school, getting a PDF of an article becomes more challenging. However, you can always ask an author for a copy of their article. They will usually be happy to hear someone is interested in reading and using their work.

What do you do with all of those PDFs? I usually keep mine in folders on my cloud storage drive, arranged by topic. For those who are more ambitious, you may want to use a reference manager like Mendeley or RefWorks, which can help keep your sources and notes organized. At the very least, take notes on each article and think about how it might be of use in your study.

Step 4: Searching for author and journal names

As you scroll through the list of articles in your search results, you should begin to notice that certain authors appear more than once. If you find an author that has written multiple articles on your topic, consider searching the AUTHOR field for that particular author. You can also search the web for that author’s Curriculum Vitae or CV (an academic resume) that will list their publications. Many authors maintain personal websites or host their CV on their university department’s webpage. Just type in their name and “CV” into a search engine. For example, you may find Michael Sherraden’s name often if your search terms are about assets and poverty. You can find his CV on the Washington University of St. Louis website.

You can also narrow down your results by journal name. As you are scrolling, you should also notice that many of the articles you’ve skimmed come from the same journals. Searching with that journal name in the JOURNAL field will allow you to narrow down your results to just that journal. For example, if you are searching for articles related to values and ethics in social work, you might want to search within the Journal of Social Work Values and Ethics. You can also navigate to the journal’s webpage and browse the abstracts of the latest issues.

Step 5: Examining references

As you begin to read your articles, you’ll notice that the authors cite additional articles that are likely relevant to your topic area. This is called archival searching. Unfortunately, this process will only allow you to see relevant articles from before the publication date. That is, the reference section of an article from 2014 will only have references from pre-2014. You can use Google Scholar’s “cited by” feature to do a future-looking archival search. Look up an article on Google Scholar and click the “cited by” link. This is a list of all the articles that cite the article you just read. Google Scholar even allows you to search within the “cited by” articles to narrow down ones that are most relevant to your topic area. For a brief discussion about archival searching check out this article by Hammond & Brown (2008): http://www.infotoday.com/cilmag/may08/Hammond_Brown.shtml. [2]

Step 6: Searching for systematic reviews and other sources

Another way to save time in literature searching is to look for articles that synthesize the results of other articles. Systematic reviews provide a summary of the existing literature on a topic. If you find one on your topic, you will be able to read one person’s summary of the literature and go deeper by reading their references. Similarly, meta-analyses and meta-syntheses have long reference lists that are useful for finding additional sources on a topic. They use data from each article to run their own quantitative or qualitative data analysis. In this way, meta-analyses and meta-syntheses provide a more comprehensive overview of a topic. To find these kinds of articles, include the term “meta-analysis,” “meta-synthesis,” or “systematic review” to your search terms. Another way to find systematic reviews is through the Cochrane Collaboration or Campbell Collaboration. These institutions are dedicated to producing systematic reviews for the purposes of evidence-based practice.

Putting it all together

Familiarizing yourself with research that has already been conducted on your topic is one of the first stages of conducting a research project and is crucial for coming up with a good research design. But where to start? How to start? Earlier in this chapter you learned about some of the most common databases that house information about published social work research. As you search for literature, you may have to be fairly broad in your search for articles. Let’s walk through an example.

Dr. Blackstone, one of the original authors of this textbook, relates an example from her research methods class: On a college campus nearby, much to the chagrin of a group of student smokers, smoking was recently banned. These students were so upset by the idea that they would no longer be allowed to smoke on university grounds that they staged several smoke-outs during which they gathered in populated areas around campus and enjoyed a puff or two together.

A student in her research methods class wanted to understand what motivated this group of students to engage in activism centered on what she perceived to be, in this age of smoke-free facilities, a relatively deviant act. Were the protesters otherwise politically active? How much effort and coordination had it taken to organize the smoke-outs? The student researcher began her research by attempting to familiarize herself with the literature on her topic, yet her search in Academic Search Complete for “college student activist smoke-outs,” yielded no results. Concluding there was no prior research on her topic, she informed her professor that she would not be able to write the required literature review since there was no literature for her to review. How do you suppose her professor responded to this news? What went wrong with this student’s search for literature?

In her first attempt, the student had been too narrow in her search for articles. But did that mean she was off the hook for completing a literature review? Absolutely not. Instead, she went back to Academic Search Complete and searched again using different combinations of search terms. Rather than searching for “college student activist smoke-outs” she tried searching for "college student activism," among other sets of terms. This time, her search yielded many related articles. Of course, they were not focused on pro-smoking activist efforts, but they were focused on her population of interest, college students, and on her broad topic of interest, activism. Her professor suggested that reading articles on college student activism might illuminate what other researchers have found in terms of motivational factors that influence college students to become involved in activism. Her professor also suggested she could switch up her search terms and look for research on activism about other sorts of deviant activities, such as marijuana use or veganism. In other words, she needed to be broader in her search for articles.

While this student found success by broadening her search for articles, her reading of those articles needed to be narrower than her search. Once she identified a set of articles to review by searching broadly, it was time to remind herself of her specific research focus: college student activist smoke-outs. Keeping in mind her particular research interest while reviewing the literature gave her the chance to think about how the theories and findings covered in prior studies might or might not apply to her particular point of focus. For example, theories on what motivates activists to get involved might tell her something about the likely reasons the students she planned to study got involved. At the same time, those theories might not cover all the particulars of student participation in smoke-outs. Thinking about the different theories then gave the student the opportunity to focus her research plans and develop a few hypotheses about her anticipated findings.

Key Takeaways

- When identifying and reading relevant literature, be broad in your search for articles but be narrow in your reading of articles.

- Conducting a literature search involves the skillful use of keywords to find relevant articles.

- It is important to narrow down the number of articles in your search results to only those articles that are most relevant to your inquiry.

Glossary

Query- search terms used in a database to find sources

Image Attributions

Magnifying glass google by Simon CC-0

Librarian at the Card Files at Senior High School in New Ulm Minnesota by David Rees CC-0

No smoking by OpenIcons CC-0

Concerns the proper statistical treatment of data and the soundness of the researchers’ statistical conclusions.