5 Experimental and Clinical Psychologists

Learning Objectives

- Define the clinical practice of psychology and distinguish it from experimental psychology.

- Explain how science is relevant to clinical practice.

- Define the concept of an empirically supported treatment and give some examples.

Who Conducts Scientific Research in Psychology?

Experimental Psychologists

Scientific research in psychology is generally conducted by people with doctoral degrees (usually the doctor of philosophy [Ph.D.]) and master’s degrees in psychology and related fields, often supported by research assistants with bachelor’s degrees or other relevant training. Some of them work for government agencies (e.g., doing research on the impact of public policies), national associations (e.g., the American Psychological Association), non-profit organizations (e.g., National Alliance on Mental Illness), or in the private sector (e.g., in product marketing and development; organizational behavior). However, the majority of them are college and university faculty, who often collaborate with their graduate and undergraduate students. Although some researchers are trained and licensed as clinicians for mental health work—especially those who conduct research in clinical psychology—the majority are not. Instead, they have expertise in one or more of the many other subfields of psychology: behavioral neuroscience, cognitive psychology, developmental psychology, personality psychology, social psychology, and so on. Doctoral-level researchers might be employed to conduct research full-time or, like many college and university faculty members, to conduct research in addition to teaching classes and serving their institution and community in other ways.

Of course, people also conduct research in psychology because they enjoy the intellectual and technical challenges involved and the satisfaction of contributing to scientific knowledge of human behavior. You might find that you enjoy the process too. If so, your college or university might offer opportunities to get involved in ongoing research as either a research assistant or a participant. Of course, you might find that you do not enjoy the process of conducting scientific research in psychology. But at least you will have a better understanding of where scientific knowledge in psychology comes from, an appreciation of its strengths and limitations, and an awareness of how it can be applied to solve practical problems in psychology and everyday life.

Scientific Psychology Blogs

A fun and easy way to follow current scientific research in psychology is to read any of the many excellent blogs devoted to summarizing and commenting on new findings. Among them are the following:

Research Digest, http://digest.bps.org.uk/

Talk Psych, http://www.talkpsych.com/

Brain Blogger, http://brainblogger.com/

Mind Hacks, http://mindhacks.com/

PsyBlog, http://www.spring.org.uk

You can also browse to http://www.researchblogging.org, select psychology as your topic, and read entries from a wide variety of blogs.

Clinical Psychologists

Psychology is the scientific study of behavior and mental processes. But it is also the application of scientific research to “help people, organizations, and communities function better” (American Psychological Association, 2011)[1]. By far the most common and widely known application is the clinical practice of psychology—the diagnosis and treatment of psychological disorders and related problems. Let us use the term clinical practice broadly to refer to the activities of clinical and counseling psychologists, school psychologists, marriage and family therapists, licensed clinical social workers, and others who work with people individually or in small groups to identify and help address their psychological problems. It is important to consider the relationship between scientific research and clinical practice because many students are especially interested in clinical practice, perhaps even as a career.

The main point is that psychological disorders and other behavioral problems are part of the natural world. This means that questions about their nature, causes, and consequences are empirically testable and therefore subject to scientific study. As with other questions about human behavior, we cannot rely on our intuition or common sense for detailed and accurate answers. Consider, for example, that dozens of popular books and thousands of websites claim that adult children of alcoholics have a distinct personality profile, including low self-esteem, feelings of powerlessness, and difficulties with intimacy. Although this sounds plausible, scientific research has demonstrated that adult children of alcoholics are no more likely to have these problems than anybody else (Lilienfeld et al., 2010)[2]. Similarly, questions about whether a particular psychotherapy is effective are empirically testable questions that can be answered by scientific research. If a new psychotherapy is an effective treatment for depression, then systematic observation should reveal that depressed people who receive this psychotherapy improve more than a similar group of depressed people who do not receive this psychotherapy (or who receive some alternative treatment). Treatments that have been shown to work in this way are called empirically supported treatments.

Empirically Supported Treatments

An empirically supported treatment is one that has been studied scientifically and shown to result in greater improvement than no treatment, a placebo, or some alternative treatment. These include many forms of psychotherapy, which can be as effective as standard drug therapies. Among the forms of psychotherapy with strong empirical support are the following:

- Acceptance and committment therapy (ACT). for depression, mixed anxiety disorders, psychosis, chronic pain, and obsessive-compulsive disorder.

- Behavioral couples therapy. For alcohol use disorders.

- Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). For many disorders including eating disorders, depression, anxiety disorders, etc.

- Exposure therapy. For post-traumatic stress disorder and phobias.

- Exposure therapy with response prevention. For obsessive-compulsive disorder.

- Family-based treatment. For eating disorders.

For a more complete list, see the following website, which is maintained by Division 12 of the American Psychological Association, the Society for Clinical Psychology: http://www.div12.org/psychological-treatments

Many in the clinical psychology community have argued that their field has not paid enough attention to scientific research—for example, by failing to use empirically supported treatments—and have suggested a variety of changes in the way clinicians are trained and treatments are evaluated and put into practice. Others believe that these claims are exaggerated and the suggested changes are unnecessary (Norcross, Beutler, & Levant, 2005)[3]. On both sides of the debate, however, there is agreement that a scientific approach to clinical psychology is essential if the goal is to diagnose and treat psychological problems based on detailed and accurate knowledge about those problems and the most effective treatments for them. So not only is it important for scientific research in clinical psychology to continue, but it is also important for clinicians who never conduct a scientific study themselves to be scientifically literate so that they can read and evaluate new research and make treatment decisions based on the best available evidence.

- American Psychological Association. (2011). About APA. Retrieved from http://www.apa.org/about ↵

- Lilienfeld, S. O., Lynn, S. J., Ruscio, J., & Beyerstein, B. L. (2010). 50 great myths of popular psychology. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell. ↵

- Norcross, J. C., Beutler, L. E., & Levant, R. F. (Eds.). (2005). Evidence-based practices in mental health: Debate and dialogue on the fundamental questions. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. ↵

Learning Objectives

- Describe the components of a literature review

- Recognize commons errors in literature reviews

Pick up nearly any book on research methods and you will find a description of a literature review. At a basic level, the term implies a survey of factual or nonfiction books, articles, and other documents published on a particular subject. Definitions may be similar across the disciplines, with new types and definitions continuing to emerge. Generally speaking, a literature review is a:

- “comprehensive background of the literature within the interested topic area” (O’Gorman & MacIntosh, 2015, p. 31). [1]

- “critical component of the research process that provides an in-depth analysis of recently published research findings in specifically identified areas of interest” (Houser, 2018, p. 109). [2]

- “written document that presents a logically argued case founded on a comprehensive understanding of the current state of knowledge about a topic of study” (Machi & McEvoy, 2012, p. 4). [3]

Literature reviews are indispensable for academic research. “A substantive, thorough, sophisticated literature review is a precondition for doing substantive, thorough, sophisticated research…A researcher cannot perform significant research without first understanding the literature in the field” (Boote & Beile, 2005, p. 3). [4] In the literature review, a researcher shows she is familiar with a body of knowledge and thereby establishes her credibility with a reader. The literature review shows how previous research is linked to the author’s project by summarizing and synthesizing what is known while identifying gaps in the knowledge base, facilitating theory development, closing areas where enough research already exists, and uncovering areas where more research is needed. (Webster & Watson, 2002, p. xiii). [5] Literature reviews are often necessary for real world social work practice. Grant proposals, advocacy briefs, and evidence-based practice rely on a review of the literature to accomplish practice goals.

A literature review is a compilation of the most significant previously published research on your topic. Unlike an annotated bibliography or a research paper you may have written in other classes, your literature review will outline, evaluate, and synthesize relevant research and relate those sources to your own research question. It is much more than a summary of all the related literature. A good literature review lays the solidifies the importance of the problem your study aims to address, defines the main ideas of your research question, and demonstrates their interrelationships.

Literature review basics

All literature reviews, whether they focus on qualitative or quantitative data, will at some point:

- Introduce the topic and define its key terms.

- Establish the importance of the topic.

- Provide an overview of the important literature on the concepts in the research question and other related concepts.

- Identify gaps in the literature or controversies.

- Point out consistent finding across studies.

- Arrive at a synthesis that organizes what is known about a topic, rather than just summarizing.

- Discuss possible implications and directions for future research.

There are many different types of literature reviews, including those that focus solely on methodology, those that are more conceptual, and those that are more exploratory. Regardless of the type of literature review or how many sources it contains, strong literature reviews have similar characteristics. Your literature review is, at its most fundamental level, an original work based on an extensive critical examination and synthesis of the relevant literature on a topic. As a study of the research on a particular topic, it is arranged by key themes or findings, which should lead up to or link to the research question.

A literature review is a mandatory part of any research project. It demonstrates that you can systematically explore the research in your topic area, read and analyze the literature on the topic, use it to inform your own work, and gather enough knowledge about the topic to conduct a research project. Literature reviews should be reasonably complete, and not restricted to a few journals, a few years, or a specific methodology or research design. A well-conducted literature review should indicate to you whether your initial research questions have already been addressed in the literature, whether there are newer or more interesting research questions available, and whether the original research questions should be modified or changed in light of findings of the literature review. The review can also provide potential answers to your research question, help identify theories that have previously been used to address similar questions, as well as provide evidence to inform policy or decision-making (Bhattacherjee, 2012). [6]

In addition, literature reviews are beneficial to you both as a researcher and as a social work scholar. By reading what others have argued and found in their work, you become familiar with how people talk about and understand your topic. During the process, you will refine your writing skills and your understanding of the topic you have chosen. The literature review also impacts the question you want to answer. As you learn more about your topic, you will clarify and redefine the research question guiding your inquiry. By completing a literature review, you ensure that you are neither repeating a study that has been done numerous times in the past, not repeating mistakes of past researchers. The contribution your research study will have depends on what others have found before you. Try to place the study you wish to do in the context of previous research and ask, “Is this contributing something new?” and “Am I addressing a gap in knowledge or controversy in the literature?”

In summary, you should conduct a literature review to:

- Locate gaps in the literature of your discipline

- Avoid “reinventing the wheel,” by repeating past studies or mistakes

- Carry on the unfinished work of other scholars

- Identify other people working in the same field

- Increase the breadth and depth of knowledge in your subject area

- Read the seminal works in your field

- Provide intellectual context for your own work

- Acknowledge opposing viewpoints

- Put your work in perspective

- Demonstrate you can find and understand previous work in the area

Common literature review errors

Literature reviews are more than a summary of the publications you find on a topic. As you have seen in this brief introduction, literature reviews are a very specific type of research, analysis, and writing. We will explore these topics more in the next chapters. As you begin your literature review, here are some common errors to avoid:

- Accepting another researcher’s finding as valid without evaluating methodology and data

- Ignoring contrary findings and alternative interpretations

- Using findings that are not clearly related to your own study or using findings that are too general

- Dedicating insufficient time to literature searching

- Simply reporting isolated statistical results, rather than synthesizing the results

- Relying too heavily on secondary sources

- Overusing quotations from sources

- Failing to justify an argument by using specific facts or theories from the literature at hand

For a quick review of some of the pitfalls and challenges a new researcher faces when they begin work, see “Get Ready: Academic Writing, General Pitfalls and (oh yes) Getting Started!”.

Key Takeaways

- Literature reviews are the first step in any research project, as they help you learn about the topic you chose to study.

- You must do more than summarize sources for a literature review. You must have something to say about them and demonstrate you understand their content.

Glossary

Literature review- a survey of factual or nonfiction books, articles, and other documents published on a particular subject

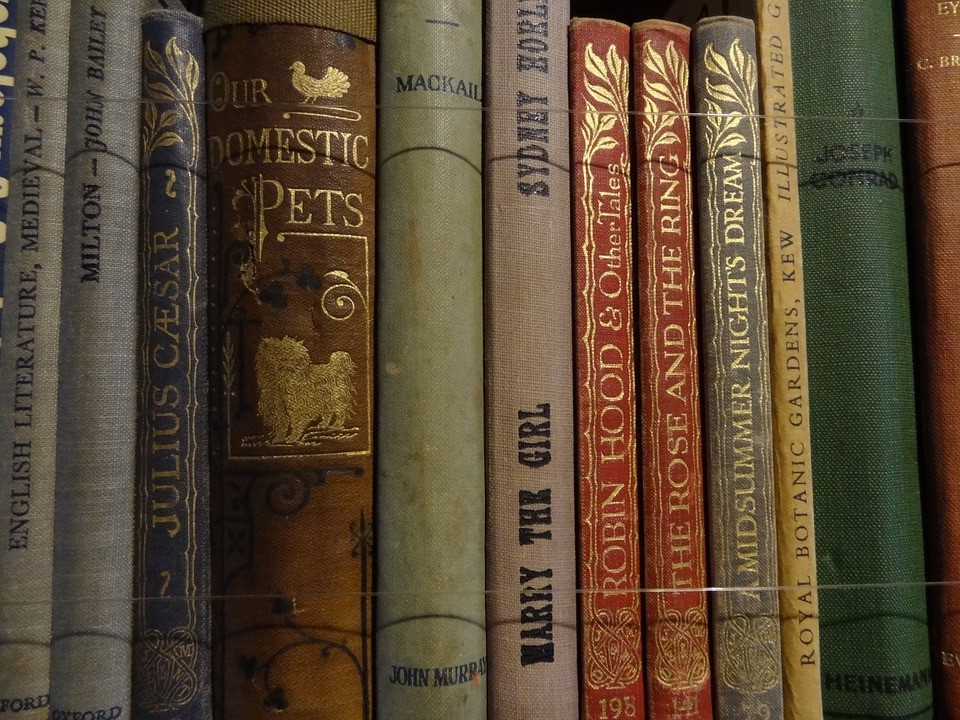

Image attributions

Book library by MVA CC-0

Learning Objectives

- List several ways in which qualitative research differs from quantitative research in psychology.

- Describe the strengths and weaknesses of qualitative research in psychology compared with quantitative research.

- Give examples of qualitative research in psychology.

What Is Qualitative Research?

This textbook is primarily about quantitative research, in part because most studies conducted in psychology are quantitative in nature. Quantitative researchers typically start with a focused research question or hypothesis, collect a small amount of numerical data from a large number of individuals, describe the resulting data using statistical techniques, and draw general conclusions about some large population. Although this method is by far the most common approach to conducting empirical research in psychology, there is an important alternative called qualitative research. Qualitative research originated in the disciplines of anthropology and sociology but is now used to study psychological topics as well. Qualitative researchers generally begin with a less focused research question, collect large amounts of relatively “unfiltered” data from a relatively small number of individuals, and describe their data using nonstatistical techniques, such as grounded theory, thematic analysis, critical discourse analysis, or interpretative phenomenological analysis. They are usually less concerned with drawing general conclusions about human behavior than with understanding in detail the experience of their research participants.

Consider, for example, a study by researcher Per Lindqvist and his colleagues, who wanted to learn how the families of teenage suicide victims cope with their loss (Lindqvist, Johansson, & Karlsson, 2008)[7]. They did not have a specific research question or hypothesis, such as, What percentage of family members join suicide support groups? Instead, they wanted to understand the variety of reactions that families had, with a focus on what it is like from their perspectives. To address this question, they interviewed the families of 10 teenage suicide victims in their homes in rural Sweden. The interviews were relatively unstructured, beginning with a general request for the families to talk about the victim and ending with an invitation to talk about anything else that they wanted to tell the interviewer. One of the most important themes that emerged from these interviews was that even as life returned to “normal,” the families continued to struggle with the question of why their loved one committed suicide. This struggle appeared to be especially difficult for families in which the suicide was most unexpected.

The Purpose of Qualitative Research

Again, this textbook is primarily about quantitative research in psychology. The strength of quantitative research is its ability to provide precise answers to specific research questions and to draw general conclusions about human behavior. This method is how we know that people have a strong tendency to obey authority figures, for example, and that female undergraduate students are not substantially more talkative than male undergraduate students. But while quantitative research is good at providing precise answers to specific research questions, it is not nearly as good at generating novel and interesting research questions. Likewise, while quantitative research is good at drawing general conclusions about human behavior, it is not nearly as good at providing detailed descriptions of the behavior of particular groups in particular situations. And quantitative research is not very good at communicating what it is actually like to be a member of a particular group in a particular situation.

But the relative weaknesses of quantitative research are the relative strengths of qualitative research. Qualitative research can help researchers to generate new and interesting research questions and hypotheses. The research of Lindqvist and colleagues, for example, suggests that there may be a general relationship between how unexpected a suicide is and how consumed the family is with trying to understand why the teen committed suicide. This relationship can now be explored using quantitative research. But it is unclear whether this question would have arisen at all without the researchers sitting down with the families and listening to what they themselves wanted to say about their experience. Qualitative research can also provide rich and detailed descriptions of human behavior in the real-world contexts in which it occurs. Among qualitative researchers, this depth is often referred to as “thick description” (Geertz, 1973)[8]. Similarly, qualitative research can convey a sense of what it is actually like to be a member of a particular group or in a particular situation—what qualitative researchers often refer to as the “lived experience” of the research participants. Lindqvist and colleagues, for example, describe how all the families spontaneously offered to show the interviewer the victim’s bedroom or the place where the suicide occurred—revealing the importance of these physical locations to the families. It seems unlikely that a quantitative study would have discovered this detail.

Table 6.3 Some contrasts between qualitative and quantitative research

| Qualitative | Quantitative |

|

1. In-depth information about relatively few people

|

1. Less depth information with larger samples

|

|

2. Conclusions are based on interpretations drawn by the investigator

|

2. Conclusions are based on statistical analyses

|

|

3. Global and exploratory

|

3. Specific and focused

|

Data Collection and Analysis in Qualitative Research

Data collection approaches in qualitative research are quite varied and can involve naturalistic observation, participant observation, archival data, artwork, and many other things. But one of the most common approaches, especially for psychological research, is to conduct interviews. Interviews in qualitative research can be unstructured—consisting of a small number of general questions or prompts that allow participants to talk about what is of interest to them—or structured, where there is a strict script that the interviewer does not deviate from. Most interviews are in between the two and are called semi-structured interviews, where the researcher has a few consistent questions and can follow up by asking more detailed questions about the topics that come up. Such interviews can be lengthy and detailed, but they are usually conducted with a relatively small sample. The unstructured interview was the approach used by Lindqvist and colleagues in their research on the families of suicide victims because the researchers were aware that how much was disclosed about such a sensitive topic should be led by the families, not by the researchers.

Another approach used in qualitative research involves small groups of people who participate together in interviews focused on a particular topic or issue, known as focus groups. The interaction among participants in a focus group can sometimes bring out more information than can be learned in a one-on-one interview. The use of focus groups has become a standard technique in business and industry among those who want to understand consumer tastes and preferences. The content of all focus group interviews is usually recorded and transcribed to facilitate later analyses. However, we know from social psychology that group dynamics are often at play in any group, including focus groups, and it is useful to be aware of those possibilities. For example, the desire to be liked by others can lead participants to provide inaccurate answers that they believe will be perceived favorably by the other participants. The same may be said for personality characteristics. For example, highly extraverted participants can sometimes dominate discussions within focus groups.

Data Analysis in Qualitative Research

Although quantitative and qualitative research generally differ along several important dimensions (e.g., the specificity of the research question, the type of data collected), it is the method of data analysis that distinguishes them more clearly than anything else. To illustrate this idea, imagine a team of researchers that conducts a series of unstructured interviews with people recovering from alcohol use disorder to learn about the role of their religious faith in their recovery. Although this project sounds like qualitative research, imagine further that once they collect the data, they code the data in terms of how often each participant mentions God (or a “higher power”), and they then use descriptive and inferential statistics to find out whether those who mention God more often are more successful in abstaining from alcohol. Now it sounds like quantitative research. In other words, the quantitative-qualitative distinction depends more on what researchers do with the data they have collected than with why or how they collected the data.

But what does qualitative data analysis look like? Just as there are many ways to collect data in qualitative research, there are many ways to analyze data. Here we focus on one general approach called grounded theory (Glaser & Strauss, 1967)[9]. This approach was developed within the field of sociology in the 1960s and has gradually gained popularity in psychology. Remember that in quantitative research, it is typical for the researcher to start with a theory, derive a hypothesis from that theory, and then collect data to test that specific hypothesis. In qualitative research using grounded theory, researchers start with the data and develop a theory or an interpretation that is “grounded in” those data. They do this analysis in stages. First, they identify ideas that are repeated throughout the data. Then they organize these ideas into a smaller number of broader themes. Finally, they write a theoretical narrative—an interpretation of the data in terms of the themes that they have identified. This theoretical narrative focuses on the subjective experience of the participants and is usually supported by many direct quotations from the participants themselves.

As an example, consider a study by researchers Laura Abrams and Laura Curran, who used the grounded theory approach to study the experience of postpartum depression symptoms among low-income mothers (Abrams & Curran, 2009)[10]. Their data were the result of unstructured interviews with 19 participants. Table 6.4 shows the five broad themes the researchers identified and the more specific repeating ideas that made up each of those themes. In their research report, they provide numerous quotations from their participants, such as this one from “Destiny:”

Well, just recently my apartment was broken into and the fact that his Medicaid for some reason was cancelled so a lot of things was happening within the last two weeks all at one time. So that in itself I don’t want to say almost drove me mad but it put me in a funk.…Like I really was depressed. (p. 357)

Their theoretical narrative focused on the participants’ experience of their symptoms, not as an abstract “affective disorder” but as closely tied to the daily struggle of raising children alone under often difficult circumstances.

| Theme | Repeating ideas |

| Ambivalence | “I wasn’t prepared for this baby,” “I didn’t want to have any more children.” |

| Caregiving overload | “Please stop crying,” “I need a break,” “I can’t do this anymore.” |

| Juggling | “No time to breathe,” “Everyone depends on me,” “Navigating the maze.” |

| Mothering alone | “I really don’t have any help,” “My baby has no father.” |

| Real-life worry | “I don’t have any money,” “Will my baby be OK?” “It’s not safe here.” |

The Quantitative-Qualitative “Debate”

Given their differences, it may come as no surprise that quantitative and qualitative research in psychology and related fields do not coexist in complete harmony. Some quantitative researchers criticize qualitative methods on the grounds that they lack objectivity, are difficult to evaluate in terms of reliability and validity, and do not allow generalization to people or situations other than those actually studied. At the same time, some qualitative researchers criticize quantitative methods on the grounds that they overlook the richness of human behavior and experience and instead answer simple questions about easily quantifiable variables.

In general, however, qualitative researchers are well aware of the issues of objectivity, reliability, validity, and generalizability. In fact, they have developed a number of frameworks for addressing these issues (which are beyond the scope of our discussion). And in general, quantitative researchers are well aware of the issue of oversimplification. They do not believe that all human behavior and experience can be adequately described in terms of a small number of variables and the statistical relationships among them. Instead, they use simplification as a strategy for uncovering general principles of human behavior.

Many researchers from both the quantitative and qualitative camps now agree that the two approaches can and should be combined into what has come to be called mixed-methods research (Todd, Nerlich, McKeown, & Clarke, 2004)[11]. (In fact, the studies by Lindqvist and colleagues and by Abrams and Curran both combined quantitative and qualitative approaches.) One approach to combining quantitative and qualitative research is to use qualitative research for hypothesis generation and quantitative research for hypothesis testing. Again, while a qualitative study might suggest that families who experience an unexpected suicide have more difficulty resolving the question of why, a well-designed quantitative study could test a hypothesis by measuring these specific variables in a large sample. A second approach to combining quantitative and qualitative research is referred to as triangulation. The idea is to use both quantitative and qualitative methods simultaneously to study the same general questions and to compare the results. If the results of the quantitative and qualitative methods converge on the same general conclusion, they reinforce and enrich each other. If the results diverge, then they suggest an interesting new question: Why do the results diverge and how can they be reconciled?

Using qualitative research can often help clarify quantitative results via triangulation. Trenor, Yu, Waight, Zerda, and Sha (2008)[12] investigated the experience of female engineering students at a university. In the first phase, female engineering students were asked to complete a survey, where they rated a number of their perceptions, including their sense of belonging. Their results were compared across the student ethnicities, and statistically, the various ethnic groups showed no differences in their ratings of their sense of belonging. One might look at that result and conclude that ethnicity does not have anything to do with one's sense of belonging. However, in the second phase, the authors also conducted interviews with the students, and in those interviews, many minority students reported how the diversity of cultures at the university enhanced their sense of belonging. Without the qualitative component, we might have drawn the wrong conclusion about the quantitative results.

This example shows how qualitative and quantitative research work together to help us understand human behavior. Some researchers have characterized qualitative research as best for identifying behaviors or the phenomenon whereas quantitative research is best for understanding meaning or identifying the mechanism. However, Bryman (2012)[13] argues for breaking down the divide between these arbitrarily different ways of investigating the same questions.