7.3 What is Learning?

Introduction

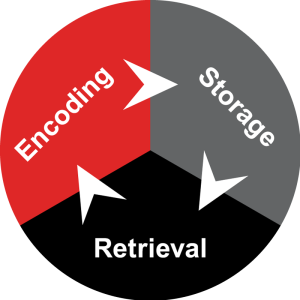

We go through three basic steps when we are learning new things: we encode, store, and retrieve that information.

Encoding (Putting Information In)

Encoding is how we first perceive information through our senses - sight, hearing, taste, touch and smell. Since we are all different, it means we will all have different ways of encoding or perceiving information.

If you were asked to learn the 7 Job Skills for the Future, your brain may store this information in the form of the circular image, or your brain may encode this information by listening to the voice of the person from the video a few times.

Both make an impression on our minds through our sense of vision and hearing. We may be able to learn them better if we write them down or talk about them with others or develop an acronym like CR SIGNS (complex problem solving, resilience, social intelligence, implementation, global citizenship, novel and adaptive thinking and self-directed learning) or by a combination of any of these examples.

Storage (Memory)

Our brains encode, or label, this content to store it in our short-term memory in case we want to think about it again. So understanding how your brain receives and stores information will be important to you being able to retrieve it when you take a test or complete a hands on task in the workplace.

Retrieval

If the information is important and we have frequent exposure to it, the brain will store it for us in case we need to use it in the future in our aptly named long-term memory. Later, the brain will allow us to recall or retrieve that image, feeling, or information so we can do something with it. This is what we call remembering.

Understanding how your brain encodes information will help you find the best ways to ensure you store it in a way you can retrieve it when required. Specific strategies for encoding, storing for easy retrieving for test taking will be covered in future chapters when we look at memory, studying, and test taking.

Activity

In this activity you will try an experiment by combining learning styles to see if it is something that works for you. The experiment will test the example of combining reading/writing and aural learning styles for better memorization.

To begin, you will start with a short segment of numbers. You will read the numbers only one time without saying them aloud. When you are finished, wait 10 seconds and try to remember the numbers in sequence by writing them down.

Click to Show

After you have finished you will repeat the experiment with a new set of numbers, but this time you will read them aloud, wait 10 seconds, and then see how easy they are to remember. During this part of the experiment you are free to say the numbers in any way you like. For example, the number 8734 could be read as eight-seven-three-four, eighty-seven thirty-four, or any combination you would like.

Click to Show

Did you find that there was a difference in your ability to memorize a short sequence of numbers for 10 seconds? Even if you were able to remember both, was the example that combined learning styles easier? What about if you had to wait for a full minute before attempting to rewrite the numbers? Would that make a difference?

Learning is Cumulative

If a new skill or knowledge is added to things we have already learned, we may see things in a new way expanding how we think in a way that cannot be reversed. A simple example might be that you know how and why you need to indent a new paragraph in your writing. However, when you learn how to format a document on your computer to do this for you, your learning expands to include this new way to accomplish the task. In essence, it can be said that every time we learn something new we are no longer the same.

All Learning Is Not the Same

The first, fundamental point to understand about learning is that there are several types of learning. Different kinds of knowledge are learned in different ways. Each of these different types of learning can require different processes that may take place in completely different parts of our brain.

For example, memorization is a form of learning that does not always require deeper understanding. You can memorize the equation for Einstein's theory of special relativity ([latex]E=mc^2[/latex]) but that is a very different type of learning than, say, being able to apply the equation correctly in a complex physics problem.

In the table below, the left column contains one of the main levels of learning, categorized by what the learning allows you to do. To the right of each category are the “skill acquired” and a set of real-world examples of what those skills might be as applied to a specific topic. This set of categories is called Bloom’s Taxonomy, and it is often used as a guide for educators when they are determining what students should learn within a course.

| Category of Learning | Skill acquired | Example: Seven Job Skills for the Future |

|---|---|---|

| Create | Produce new or original work | Create a plan for improvement for developing the skill you identified. Monitor and evaluate plan as you execute so you can measure results. |

| Evaluate | Justify or support an idea or decision | Decide which skill you will develop based on your analysis. |

| Analyze | Draw connections | Analyze what skills are required in your current job that you may not be strong in, to determine how developing one or more skills will help you succeed. |

| Apply | Use information in new ways | Apply your understanding of your environment and skills to identify where developing your skills in these 7 areas would have been beneficial and what areas you are skilled at already. |

| Understand/ Comprehend | Explain ideas or concepts | Explain what each one means. |

| Remember | Recall facts and basic concepts | Recite the 7 Job Skills for the Future. |

Know Your Purpose

When you engage in any learning activity, take the time to identify the purpose of the lesson or, what you will do with the knowledge once you have attained it. Considering your purpose for even a brief moment before you start anything, allows your brain to retrieve what it already knows, which will help you encode and store new information to store, which reinforces your learning, making it easier to retrieve the new, expanded information from your memory.

Knowing your purpose engages the learning process, which can be seen more like a cycle, and not a linear process as shown above.

Considering your purpose before you begin to read, listen, talk, or write can help a great deal when it comes to making decisions on how to go about learning the information in a way that will work for you.

- If you are asked to read a paragraph to summarize the main idea you would read it very differently than if you were to read a paragraph to identify spelling errors.

- Using flashcards to help memorize definitions does not really help you if you need to analyze a specific business, apply those terms to evaluate it's success and create an action plan for the business to improve.

- Memorizing math formulas may not be the best way to study for a math test. Instead, practicing problem-solving with the actual formulas is a much better approach. The key is to make certain the learning activity fits your needs.

Workplace Applications

In the workplace we see how this applies as well:

- Reading and understanding the muscles of the shoulder is very different than being able to understand how the shoulder moves

- Understanding that you need to image a dislocated shoulder is very different from being able to accurately position the patient to get the best view of the dislocation for the radiologist to diagnose

- Knowing the muscles of the shoulder does not mean you can manipulate it correctly without harming a patient

In the next section, you will explore how your attitude, motivation and learning preference impact your learning.

Applying Your Knowledge

Applying Your Knowledge

"2.2 What is Learning?" from Fanshawe SOAR by Kristen Cavanagh is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.