8.3 When Conversations Become “Crucial”

According to Patterson et al., authors of Crucial Conversations, a conversation becomes “crucial” when the following three conditions are met (Patterson et al., 2012):

There is something significant on the line—be it a project’s success, a career opportunity, or a personal relationship. The potential outcome of the conversation carries weight, and failing to address the issue effectively could lead to major consequences.

These differences may arise from varying experiences, beliefs, or interpretations of the situation. Because the subject matter is often important to everyone involved, clashing perspectives can make the conversation more tense or complex.

Participants feel passionate about the topic or perceive a threat to their values, self-esteem, or goals. Intense emotional undercurrents can escalate a disagreement quickly or cause people to shut down, making it harder to maintain an open, constructive dialogue.

Response to Crucial Conversations

Under these conditions, communication and constructive dialogue often break down, and people usually resort to one of two unproductive behaviours:

Silence (Flight Response)

Silence can be understood as the “flight” in the body’s fight or flight response (see alarm phase from Chapter 5). Here, an individual withdraws from active participation to protect themselves from a perceived threat. Rather than engage in direct confrontation, they erect a metaphorical wall to avoid further discomfort, criticism, or tension. Such tactics may feel safe in the moment, but they stall progress and leave the conflict unresolved.

Silence can manifest in several ways, including:

- Masking: Hiding true feelings through vague comments.

- Avoiding: Steering clear of the real issue by changing the subject instead of addressing it.

- Withdrawing: Physically or emotionally pulling away from the interaction.

- Quietness: Responding with minimal or no verbal feedback, offering only nods or short phrases.

- Sarcasm: Using cynical or mocking remarks to deflect tension.

Violence (Fight Response)

On the opposite end of the spectrum lies violence, or the “fight” response. This response does not mean physical violence; rather, the individual seeks to regain control of the conversation using forceful or controlling tactics that disrupt open dialogue and erode mutual respect.

Individuals pursuing this path might adopt the following strategies:

- Trying to Take Control: Cutting others off, refusing to listen, or monopolizing the dialogue.

- Labelling Others: Assigning negative stereotypes or tags to discount someone’s perspective.

- Attacking: Verbally harming another person’s ideas, character, or intentions.

- Name-Calling & Yelling: Raising their voice to intimidate or humiliate.

- Hurling Personal Insults & Incredulity: Expressing disbelief in a way that demeans the other speaker.

Pulling Yourself Out of Silence or Violence

The first step toward effective communication in a crucial conversation is recognizing when you (or others) have shifted into silence or violence. This requires a high amount of self-awareness and the ability to pause in the moment and reflect on what you are feeling and thinking in the moment (concepts discussed in Chapter 6). Ask yourself:

- “What is really important here?”

- “What do I truly want from this conversation?”

Centering on your genuine goals, such as finding a resolution or maintaining a relationship, can help recalibrate your approach. Recalling your objectives and focusing on the end result helps resist the urge to succumb to unproductive fight-or-flight behaviours.

Discerning Fact, Interpretation and Feeling

Another common challenge in heated conversations is failing to distinguish facts from interpretations:

- Facts are typically objective, verifiable, and supported by evidence (e.g., direct quotes, observable actions, scientific research, documented dates and events). They remain true regardless of your personal interpretation or emotional state.

- Interpretations (or subjective stories) reflect your personal opinions, beliefs, biases, or assumptions. They may accompany an emotional response or assumption about someone’s intent.

- Feelings can be described as internal truths. They are not objective or verifiable in the same way facts are; however, they remain real and valid experiences. As discussed in Chapter 6, statements like “I feel hurt” or “I feel anxious” reflect an emotional state rather than an interpretation (or thought). Because feelings reflect a person’s lived experience, they cannot and should not be refuted in the same way interpretations can. Instead, they should be acknowledged as meaningful insights into a person’s inner world, whether it’s your own or someone else’s.

Activity

Text Description

- Kevin Hart is a very funny man. Fact or Interpretation?

- The capital of Canada is Ottawa. Fact or Interpretation?

- AJ speaks loudly in the class. Fact or Interpretation?

- AJ said, “Everything on the lecture slides is fair game for your test.” Fact or Interpretation?

- Donald Trump is an arrogant person and a liar. Fact or Interpretation?

- The Pope is a very humble and kind person. Fact or Interpretation?

- In 1776, the United States declared its independence from Great Britain. Fact or Interpretation?

- My mom yelled at me for not cleaning up my room. Fact or Interpretation?

- Tim Hortons serves the best coffee in Canada. Fact or Interpretation?

- The rights and freedoms of minority groups living in Canada are under attack. Fact or Interpretation?

Correct Answers:

- Interpretation: Humour is subjective; what’s funny to one person may not be to another.

- Fact: This is a verifiable geographical fact.

- Interpretation: “Loudly” is an interpretation unless it can be measured (e.g., decibel level).

- Fact: A direct quote is a fact (assuming it was accurately recorded).

- Interpretation: “Arrogant” is an opinion; “liar” is an accusation that would need specific, verifiable examples to be factual.

- Interpretation: “Humble” and “kind” are subjective qualities open to interpretation.

- Fact: A documented historical event.

- Interpretation: “Yelled” might be factual if referring to volume, but the reason (“for not cleaning”) is an interpretation unless explicitly stated by her.

- Interpretation: “Best” is subjective, as taste preferences vary.

- Interpretation: While there may be legal debates or policies affecting rights, “under attack” is an interpretation that implies intent and severity.

Problems arise when interpretations are treated as though they are indisputable facts. This confusion often leads to emotional arguments and conflict escalation. Grounding discussions in observable, measurable data can reduce misunderstandings and foster a more constructive dialogue.

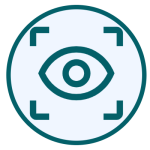

It is helpful to ground statements in observable facts before sharing how you interpreted them. Consider the difference between these two statements:

Image Description

- Example #1: “It’s clear that you don’t care about me or our relationship”

- Example #2: “You have not returned any of my texts or phone calls for the past three days. Because of this, it seems like you don’t really care about our relationship”

The first sentence is rooted in interpretation, not fact. It assumes the other person’s intent and emotions, which may or may not be true. This phrasing is likely to trigger defensiveness rather than meaningful dialogue and resolution). The second sentence acknowledges an interpretation but frames it as a personal perception rather than an accusation. This allows space for discussion and clarification rather than immediate conflict.

Other Workplace Conflict Examples

| Interpretation only – assumes intent | Fact + Interpretation |

|---|---|

| “You never listen to my ideas in meetings.” | “In the last three meetings, I’ve shared ideas, but you haven’t responded or acknowledged them. It makes me feel like my input isn’t valued.” |

| “You don’t care about our friendship anymore.” | “We used to hang out every weekend, but we haven’t made any plans in over a month. It makes me wonder if our friendship is as important to you as it is to me.” |

By consciously recognizing this pattern (Fact → Interpretation → Story), you can improve your critical thinking, emotional intelligence, and communication skills, leading to more rational and productive conversations and the pursuit of higher-level wellness.

Freeing the Other Side from Silence or Violence

Even if you manage to maintain composure and use facts to your advantage, your conversation partner(s) may still respond with silence or violence. Here are three key strategies that may help restore safety and trust in the dialogue:

Offer a specific, genuine apology for your contribution to the tension. An insincere or vague apology (e.g., “I’m sorry if you felt that way”) can be counterproductive. Instead, clearly acknowledge your behaviour or words that led to the conflict.

Identify a shared goal that both parties care about. This might include a successful project outcome or a valued relationship. Focusing on common ground reduces defensiveness and fosters collaboration.

Contrasting statements clarify what you are not trying to do, followed by what you are trying to accomplish. This can dispel suspicion about hidden motives.

“Confronting Professor X” Scenario

“Confronting Professor X” Scenario

Let’s go back to our original scenario and help the Professor out with a contrasting statement using this formula:

“I don’t want X; all I want is Y.”

X = What the other person might wrongly assume (e.g., control, criticism, a fight)

Y = Mutual purpose – something that both parties care about (e.g., understanding, teamwork, a solution)

You: “I don’t think that’s fair. You can’t expect us to write down everything you say!”

Professor X: “I don’t expect you to write down everything I say. I do want to ensure there is a clear, consistent standard for all students so they can succeed.”