9.1 Understanding Team Design Characteristics

Learning Objectives

- Distinguish between groups and teams.

- List the factors leading to the rise in the use of teams.

- Explain how tasks and roles affect teams.

- Identify different types of teams.

- Identify team design considerations.

Effective teams give companies a significant competitive advantage. In a high-functioning team, the sum is truly greater than the parts. Team members not only benefit from each other’s diverse experiences and perspectives but also stimulate each other’s creativity. Plus, for many people, working in a team can be more fun than working alone.

Differences Between Groups and Teams

Organizations consist of groups of people. What exactly is the difference between a group and a team? A group is a collection of individuals. Within an organization, groups might consist of project-related groups such as a product group or division, or they can encompass an entire store or branch of a company. The performance of a group consists of the inputs of the group minus any process losses, such as the quality of a product, ramp-up time to production, or the sales for a given month. Process loss is any aspect of group interaction that inhibits group functioning.

Why do we say group instead of team? A collection of people is not a team, though they may learn to function in that way. A team is a cohesive coalition of people working together to achieve mutual goals. Being on a team does not equate to a total suppression of personal agendas, but it does require a commitment to the vision and involves each individual working toward accomplishing the team’s objective. Teams differ from other types of groups in that members are focused on a joint goal or product, such as a presentation, discussing a topic, writing a report, creating a new design or prototype, or winning a team Olympic medal. Moreover, teams also tend to be defined by their relatively smaller size. For example, according to one definition, “A team is a small number of people with complementary skills who are committed to a common purpose, performance goals, and approach for which they are mutually accountable” (Katzenbach & Smith, 1993).

The purpose of assembling a team is to accomplish larger, more complex goals than what would be possible for an individual working alone or even the simple sum of several individuals working independently. Teamwork is also needed in cases in which multiple skills are tapped or where buy-in is required from several individuals. Teams can, but do not always, provide improved performance. Working together to further a team agenda seems to increase mutual cooperation between what are often competing factions. The aim and purpose of a team is to perform, get results, and achieve victory in the workplace. The best managers are those who can gather together a group of individuals and mold them into an effective team.

The key properties of a true team include collaborative action in which, along with a common goal, teams have collaborative tasks. Conversely, in a group, individuals are responsible only for their own area. They also share the rewards of strong team performance with their compensation based on shared outcomes. Compensation of individuals must be based primarily on a shared outcome, not individual performance. Members are also willing to sacrifice for the common good, in which individuals give up scarce resources for the common good instead of competing for those resources. For example, in soccer and basketball teams, the individuals actively help each other, forgo their own chance to score by passing the ball, and win or lose collectively as a team.

Team Tasks

Teams differ in terms of the tasks they are trying to accomplish. Richard Hackman identified three major classes of tasks: production tasks, idea-generation tasks, and problem-solving tasks (Hackman, 1976). Production tasks include actually making something, such as a building, product, or marketing plan.Idea-generation tasks deal with creative tasks, such as brainstorming a new direction or creating a new process. Problem-solving tasks refer to coming up with plans for actions and making decisions. For example, a team may be charged with coming up with a new marketing slogan, which is an idea-generation task, while another team might be asked to manage an entire line of products, including making decisions about products to produce, managing the production of the product lines, marketing them, and staffing their division. The second team has all three types of tasks to accomplish at different points in time.

Another key to understanding how tasks are related to teams is to understand their level of task interdependence. Task interdependence refers to the degree to which team members are dependent on one another to get information, support, or materials from other team members to be effective. Research shows that self-managing teams are most effective when their tasks are highly interdependent (Langfred, 2005; Liden, Wayne, & Bradway, 1997). There are three types of task interdependence. Pooled interdependence exists when team members may work independently and simply combine their efforts to create the team’s output. For example, when students meet to divide the section of a research paper and one person simply puts all the sections together to create one paper, the team is using the pooled interdependence model. However, they might decide that it makes more sense to start with one person writing the introduction of their research paper, then the second person reads what was written by the first person and, drawing from this section, writes about the findings within the paper. Using the findings section, the third person writes the conclusions. If one person’s output becomes another person’s input, the team would be experiencing sequential interdependence. And finally, if the student team decided that in order to create a top-notch research paper, they should work together on each phase of the research paper so that their best ideas would be captured at each stage, they would be undertaking reciprocal interdependence. Another important type of interdependence that is not specific to the task itself is outcome interdependence, in which the rewards that an individual receives depend on the performance of others.

Team Roles

Studies show that individuals who are more aware of team roles and the behaviour required for each role perform better than individuals who do not. This fact remains true for both student project teams as well as work teams, even after accounting for intelligence and personality (Mumford et al., 2008). Early research found that teams tend to have two categories of roles, consisting of those related to the tasks at hand and those related to the team’s functioning. For example, teams that focus only on production at all costs may be successful in the short run, but if they pay no attention to how team members feel about working 70 hours a week, they are likely to experience high turnover.

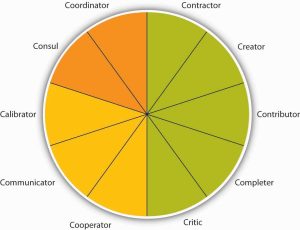

Teams are based on many roles being carried out, as summarized by the Team Role Typology. These 10 roles include task roles (contractor, creator, contributor, completer, and critic), social roles (calibrator, communicator, and cooperator), and boundary-spanning roles (consul and coordinator). These 10 roles include task roles (green), social roles (yellow), and boundary-spanning roles (orange) (Mumford et. al., 2008).

B Team leadership is effective when leaders are able to adapt the roles they are contributing or asking others to contribute to fit what the team needs, given its stage and the tasks at hand (Kozlowski et al., 1996; Kozlowski et al., 1996). Ineffective leaders might always engage in the same task role behaviours, when what they really need is to focus on social roles, put disagreements aside, and get back to work. While these behaviours can be effective from time to time, if the team doesn’t modify its role behaviours as things change, they most likely will not be effective.

Task Roles

Five roles make up the task portion of the typology. The contractor role includes behaviours that serve to organize the team’s work, including creating team timelines, production schedules, and task sequencing. The creator role deals more with changes in the team’s task process structure. For example, reframing the team goals and looking at the context of goals would fall under this role. The contributor role is important because it brings information and expertise to the team. This role is characterized by sharing knowledge and training with those who have less expertise to strengthen the team. Research shows that teams with highly intelligent members and evenly distributed workloads are more effective than those with uneven workloads (Ellis et al., 2003). The completer role is also important, as it transforms ideas into action. Behaviours associated with this role include following up on tasks, such as gathering needed background information or summarizing the team’s ideas into reports. Finally, the critic role includes “devil’s advocate” behaviours that go against the assumptions being made by the team.

Social Roles

Social roles serve to keep the team operating effectively. When the social roles are filled, team members feel more cohesive, and the group is less prone to suffer process losses or biases such as social loafing, groupthink, or a lack of participation from all members. Three roles fall under the umbrella of social roles. The cooperator role includes supporting those with expertise toward the team’s goals. This is a proactive role. The communicator role includes behaviours that are targeted at collaboration, such as practicing good listening skills and appropriately using humour to diffuse tense situations. Having a good communicator helps the team feel more open to sharing ideas. The calibrator role is an important one that serves to keep the team on track in terms of suggesting any needed changes to the team’s process. This role includes initiating discussions about potential team problems, such as power struggles or other tensions. Similarly, this role may involve settling disagreements or pointing out what is working and what is not in terms of team process.

Boundary-Spanning Roles

The final two goals are related to activities outside the team that help to connect the team to the larger organization (Anacona, 1990; Anacona, 1992; Druskat & Wheeler, 2003). Teams that engage in a greater level of boundary-spanning behaviours increase their team effectiveness (Marrone, Tesluk, & Carson, 2007). The consul role includes gathering information from the larger organization and informing those within the organization about team activities, goals, and successes. Often, the consul role is filled by team managers or leaders. The coordinator role includes interfacing with others within the organization so that the team’s efforts are in line with other individuals and teams within the organization.

Types of Teams

There are several types of temporary teams. In fact, one-third of all teams in the United States are temporary in nature (Gordon, 1992). An example of a temporary team is a task force that is asked to address a specific issue or problem until it is resolved. Other teams may be temporary or ongoing, such as product development teams. In addition, matrix organizations have cross-functional teams in which individuals from different parts of the organization staff the team, which may be temporary or long-standing in nature.

Virtual teams are teams in which members are not located in the same physical place. They may be in different cities, states, or even different countries. Some virtual teams are formed by necessity, such as to take advantage of lower labour costs in different countries, with upwards of 8.4 million individuals working virtually in at least one team (Ahuja & Galvin, 2003). As of 2023, estimates suggest that 14 million people work online (Kässi et. al., 2021). Often, virtual teams are formed to take advantage of distributed expertise or time—the needed experts may be living in different cities. A company that sells products around the world, for example, may need technologists who can solve customer problems at any hour of the day or night. It may be difficult to find the calibre of people needed who would be willing to work at 2:00 a.m. on a Saturday, for example.

Despite potential benefits, virtual teams present special management challenges. Managers often think that they have to see team members working in order to believe that work is being done. Because this kind of oversight is impossible in virtual team situations, it is important to devise evaluation schemes that focus on deliverables. Are team members delivering what they said they would? In self-managed teams, are team members producing the results that the team decided to measure itself on?

Another special challenge of virtual teams is building trust. Will team members deliver results just as they would in face-to-face teams? Can members trust each other to do what they said they would do? Companies often invest in bringing a virtual team together at least once so members can get to know each other and build trust (Kirkman et al., 2002). In manager-led virtual teams, managers should be held accountable for their team’s results and evaluated on their ability as a team leader.

Finally, communication is especially important in virtual teams, be it through e-mail, test messages, phone calls, conference calls, or project management tools that help organize work. If individuals in a virtual team are not fully engaged and tend to avoid conflict, team performance can suffer (Montoya-Weiss, Massey, & Song, 2001). A wiki is an Internet-based method for many people to collaborate and contribute to a document or discussion. Essentially, the document remains available for team members to access and amend at any time. The most famous example is Wikipedia, which is gaining traction as a way to structure project work globally and get information into the hands of those who need it. Empowered organizations put information into everyone’s hands (Kirkman & Rosen, 2000). Research shows that empowered teams are more effective than those that are not empowered (Mathieu, Gilson, & Ruddy, 2006).

Top management teams are appointed by the chief executive officer (CEO) and, ideally, reflect the skills and areas that the CEO considers vital for the company. There are no formal rules about top management team design or structure. The top team often includes representatives from functional areas, such as finance, human resources, and marketing, or key geographic areas, such as Europe, Asia, and North America. Depending on the company, other areas may be represented, such as legal counsel or the company’s chief technologist. Typical top management team member titles include chief operating officer (COO), chief financial officer (CFO), chief marketing officer (CMO), or chief technology officer (CTO). Because CEOs spend an increasing amount of time outside their companies (e.g., with suppliers, customers, and regulators), the role of the COO has taken on a much higher level of internal operating responsibilities. In most American companies, the CEO also serves as chairman of the board and can have the additional title of president. Companies have top teams to help set the company’s vision and strategic direction. Top teams make decisions on new markets, expansions, acquisitions, or divestitures. The top team is also important for its symbolic role: How the top team behaves dictates the organization’s culture and priorities by allocating resources and by modelling behaviours that will likely be emulated lower down in the organization. Importantly, the top team is most effective when team composition is diverse—functionally and demographically when it can truly operate as a team, not just as a group of individual executives (Carpenter, Geletkanycz, & Sanders, 2004). There is a similar arrangement at private golf clubs, with an added component of a board of directors, which is elected by the club and assists in the vision of the organization.

Team Leadership and Autonomy

Teams also vary in terms of how they are led. Traditional manager-led teams are teams in which the manager serves as the team leader. The manager assigns work to other team members. These types of teams are the most natural to form, with managers having the power to hire and fire team members and being held accountable for the team’s results.

Self-managed teams are a new form of team that rose in popularity with the Total Quality Movement in the 1980s. Unlike manager-led teams, these teams manage themselves and do not report directly to a supervisor. Instead, team members select their own leader, and they may even take turns in the leadership role. Self-managed teams also have the power to select new team members. As a whole, the team shares responsibility for a significant task, such as the assembly of an entire car. The task is ongoing rather than a temporary task such as a charity fund drive for a given year.

Organizations began to use self-managed teams as a way to reduce hierarchy by allowing team members to complete tasks and solve problems on their own. The benefits of self-managed teams extend much further. Research has shown that employees in self-managed teams have higher job satisfaction, increased self-esteem, and grow more on the job. The benefits to the organization include increased productivity, increased flexibility, and lower turnover. Self-managed teams can be found at all levels of the organization, and they bring particular benefits to lower-level employees by giving them a sense of ownership of their jobs that they may not otherwise have. The increased satisfaction can also reduce absenteeism, because employees do not want to let their team members down.

Typical team goals are improving quality, reducing costs, and meeting deadlines. Teams also have a “stretch” goal—a goal that is difficult to reach but important to the business unit. Many teams also have special project goals.

Self-managed teams are empowered teams, which means that they have the responsibility as well as the authority to achieve their goals. Team members have the power to control tasks and processes and to make decisions. Research shows that self-managed teams may be at a higher risk of suffering from negative outcomes due to conflict, so it is important that they are supported with training to help them deal with conflict effectively (Alper, Tjosvold, & Law, 2000; Langfred, 2007). Self-managed teams may still have a leader who helps them coordinate with the larger organization (Morgeson, 2005).

| Traditionally managed teams | Self-managed teams | Self-directed team |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Team leadership is a major determinant of how autonomous a team can be.

Designing Effective Teams

Designing an effective team means making decisions about team composition (who should be on the team), team size (the optimal number of people on the team), and team diversity (should team members be of similar background, such as all engineers, or of different backgrounds). Answering these questions will depend, to a large extent, on the type of task that the team will be performing. Teams can be charged with a variety of tasks, from problem-solving to generating creative and innovative ideas to managing the daily operations of a manufacturing plant. In the turf department, teams could be tasked to find ways to complete daily jobs effectively and efficiently.

Who Are the Best Individuals for the Team?

A key consideration when forming a team is to ensure that all the team members are qualified for the roles they will fill for the team. This process often entails understanding the knowledge, skills, and abilities (KSAs) of team members as well as the personality traits needed before starting the selection process (Humphrey et al., 2007). When talking to potential team members, be sure to communicate the job requirements and norms of the team. To the degree that this is not possible, such as when already existing groups are utilized, think of ways to train the team members as much as possible to help ensure success. In addition to task knowledge, research has shown that individuals who understand the concepts covered in this chapter and in this book, such as conflict resolution, motivation, planning, and leadership, actually perform better on their jobs.

How Large Should My Team Be?

The ideal size for a team depends on the task at hand. Groups larger than 10 members tend to be harder to coordinate and often break into subteams to accomplish the work at hand. Interestingly, research has shown that regardless of team size, the most active team member speaks 43% of the time. The difference is that the team member who participates the least in a 3-person team is still active 23% of the time versus only 3% in a 10-person team (McGrath, 1984; Solomon, 1960). When deciding team size, a good rule of thumb is a size of two to 20 members. Research shows that groups with more than 20 members have less cooperation (Gratton & Erickson, 2007).

The majority of teams have 10 members or fewer, because the larger the team, the harder it is to coordinate and interact as a team. With fewer individuals, team members are more able to work through differences and agree on a common plan of action. They have a clearer understanding of others’ roles and greater accountability to fulfill their roles (remember social loafing?). Some tasks, however, require larger team sizes because of the need for diverse skills or because of the complexity of the task. In those cases, the best solution is to create subteams in which one member from each subteam is a member of a larger coordinating team. The relationship between team size and performance seems to greatly depend on the level of task interdependence, with some studies finding larger teams outproducing smaller teams and other studies finding just the opposite (Campion, Medsker, & Higgs, 1993; Magjuka & Baldwin, 1991; Vinokur-Kaplan, 1995). The bottom line is that team size should be matched to the goals of the team.

How Diverse Should My Team Be?

Team composition and team diversity often go hand in hand. Teams whose members have complementary skills are often more successful because members can see each other’s blind spots. One team member’s strengths can compensate for another’s weaknesses (Jackson, Joshi, & Erhardt, 2003; van Knippenberg, De Dreu, & Homan, 2004). For example, consider the challenge that companies face when trying to forecast future sales of a given product. Workers who are educated as forecasters have the analytic skills needed for forecasting, but these workers often lack critical information about customers. Salespeople, in contrast, regularly communicate with customers, which means they’re in the know about upcoming customer decisions. But salespeople often lack the analytic skills, discipline, or desire to enter this knowledge into spreadsheets and software that will help a company forecast future sales. Putting forecasters and salespeople together on a team tasked with determining the most accurate product forecast each quarter makes the best use of each member’s skills and expertise.

Diversity in team composition can help teams come up with more creative and effective solutions. Research shows that teams that believe in the value of diversity perform better than teams that do not (Homan et al., 2007). The more diverse a team is in terms of expertise, gender, age, and background, the greater the group’s ability to avoid the problems of groupthink (Surowiecki, 2005). For example, different educational levels for team members were related to more creativity in R&D teams and faster time to market for new products (Eisenhardt & Tabrizi, 1995; Shin & Zhou, 2007). Members will be more inclined to make different kinds of mistakes, which means that they’ll be able to catch and correct those mistakes.

Exercises

- Think of the last team you were in. Did the task you were asked to do affect the team? Why or why not?

- Which of the 10 work roles do you normally take in a team? How difficult or easy do you think it would be for you to take on a different role?

- Have you ever worked in a virtual team? If so, what were the challenges and advantages of working virtually?

- How large do you think teams should be and why?

“9.3: Understanding Team Design Characteristics” from Organizational Behavior by LibreTexts is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.