7.0 What Is Stress?

Learning Objectives

- Define the General Adaptation Syndrome.

- Explain what stressors are.

- Discuss the outcomes of stress.

- Describe the individual differences in experienced stress.

Gravity. Mass. Magnetism. These words come from the physical sciences. And so does the term stress. In its original form, the word stress relates to the amount of force applied to a given area. A steel bar stacked with bricks is being stressed in ways that can be measured using mathematical formulas. In human terms, psychiatrist Peter Panzarino notes, “Stress is simply a fact of nature—forces from the outside world affecting the individual” (Panzarino, 2008). The professional, personal, and environmental pressures of modern life exert their forces on us every day. Some of these pressures are good. Others can wear us down over time.

Stress is defined by the physiological or psychological response to internal or external stressors(American Psychological Association, 2018). Stress is an inevitable feature of life. It is the force that gets us out of bed in the morning, motivates us at the gym, and inspires us to work.

As you will see in the sections below, stress is a given factor in our lives. We may not be able to avoid stress completely, but we can change how we respond to stress, which is a major benefit. Our ability to recognize, manage, and maximize our response to stress can turn an emotional or physical problem into a resource.

According to Statistics Canada, “just over 4.1 million people indicated that they experienced high or very high levels of work-related stress, representing 21.2% of all employed people. The most common causes of work-related stress included a heavy workload, which affected 23.7% of employed people, as well as balancing work and personal life (15.7% of employed people). Women (22.7%) were more likely than men (19.7%) to experience high or very high levels of work-related stress” (Statistics Canada, 2023).

The Stress Process

Our basic human functions, breathing, blinking, heartbeat, digestion, and other unconscious actions, are controlled by our lower brains. Just outside this portion of the brain is the semiconscious limbic system, which plays a large part in human emotions. Within this system is an area known as the amygdala. The amygdala is responsible for, among other things, stimulating fear responses. Unfortunately, the amygdala cannot distinguish between meeting a 10:00 a.m. marketing deadline and escaping a burning building.

Human brains respond to outside threats to our safety with a message to our bodies to engage in a “fight-or-flight” response (Cannon, 1915). Our bodies prepare for these scenarios with an increased heart rate, shallow breathing, and wide-eyed focus. Even digestion and other functions are stopped in preparation for the fight-or-flight response. While these traits allowed our ancestors to flee the scene of their impending doom or engage in a physical battle for survival, most crises at work are not as dramatic as this.

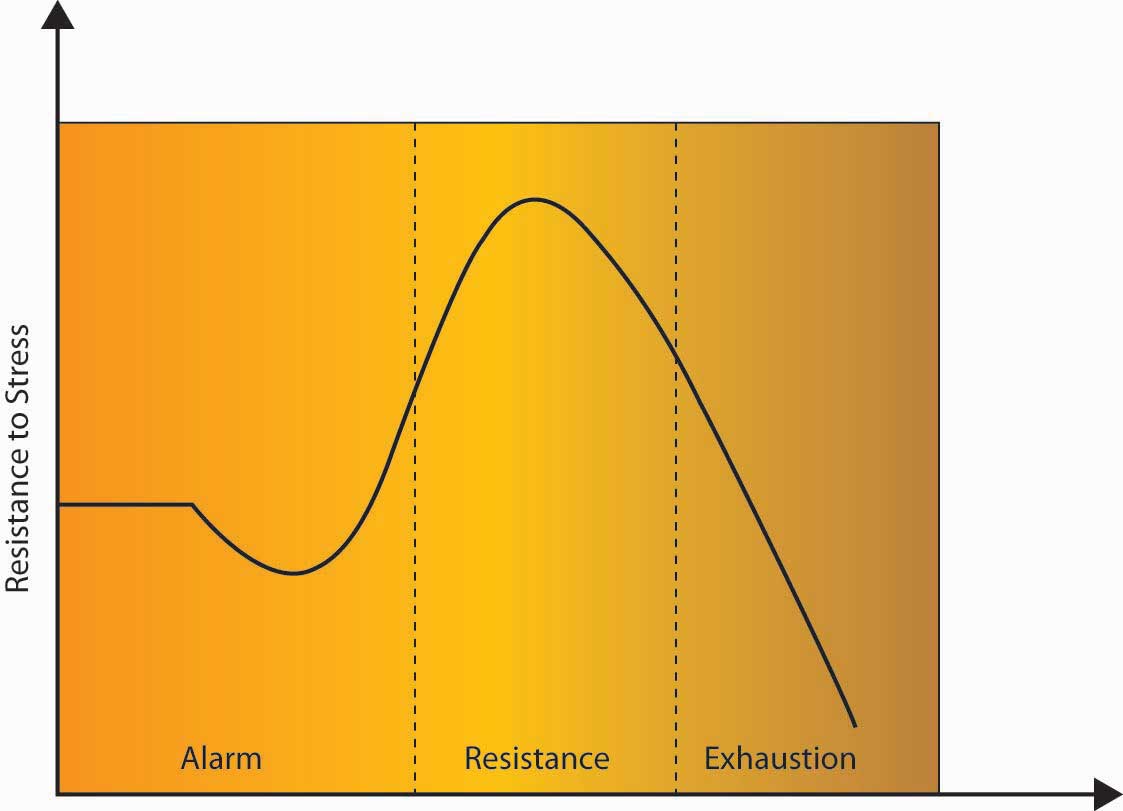

Hans Selye, one of the founders of the American Institute of Stress, spent his life examining the human body’s response to stress. As an endocrinologist who studied the effects of adrenaline and other hormones on the body, Selye believed that unmanaged stress could create physical diseases such as ulcers and high blood pressure, and psychological illnesses such as depression. He hypothesized that stress played a general role in disease by exhausting the body’s immune system and termed this the General Adaptation Syndrome (GAS) (Selye, 1946; Selye, 1976).

In the alarm phase of stress, an outside stressor jolts the individual, insisting that something must be done. It may help to think of this as the fight-or-flight moment in the individual’s experience. If the response is sufficient, the body will return to its resting state after having successfully dealt with the source of stress.

In the resistance phase, the body begins to release cortisol and draws on reserves of fats and sugars to find a way to adjust to the demands of stress. This reaction works well for short periods of time, but it is only a temporary fix. Individuals forced to endure the stress of cold and hunger may find a way to adjust to lower temperatures and less food. While it is possible for the body to “adapt” to such stresses, the situation cannot continue. The body is drawing on its reserves, like a hospital using backup generators after a power failure. It can continue to function by shutting down unnecessary items like large overhead lights, elevators, televisions, and most computers, but it cannot proceed in that state forever.

In the exhaustion phase, the body has depleted its stores of sugars and fats, and the prolonged release of cortisol has caused the stressor to significantly weaken the individual. Disease results from the body’s weakened state, leading to death in the most extreme cases. This eventual depletion is why we’re more likely to reach for foods rich in fat or sugar, caffeine, or other quick fixes that give us energy when we are stressed. Selye referred to stress that led to disease as distress and stress that was enjoyable or healing as eustress.

Workplace Stressors

Stressors are events or contexts that cause a stress reaction by elevating levels of adrenaline and forcing a physical or mental response. The key to remember about stressors is that they aren’t necessarily a bad thing. The saying “the straw that broke the camel’s back” applies to stressors. Having a few stressors in our lives may not be a problem, but because stress is cumulative, having many stressors day after day can cause a buildup that becomes a problem. The American Psychological Association surveys American adults about their stresses annually. Topping the list of stressful issues are money, work, and housing (American Psychological Association, 2007). But in essence, we could say that all three issues come back to the workplace. How much we earn determines the kind of housing we can afford, and when job security is questionable, home life is generally affected as well.

Understanding what can potentially cause stress can help avoid negative consequences. Now we will examine the major stressors in the workplace. A major category of workplace stressors is role demands. In other words, some jobs and some work contexts are more potentially stressful than others.

Role Demands

Role ambiguity refers to vagueness in relation to what our responsibilities are. If you have started a new job and felt unclear about what you were expected to do, you have experienced role ambiguity. Having high role ambiguity is related to higher emotional exhaustion, more thoughts of leaving an organization, and lowered job attitudes and performance (Fisher & Gittelson, 1983; Jackson & Shuler, 1985; Örtqvist & Wincent, 2006). Role conflict refers to facing contradictory demands at work. For example, your manager may want you to increase customer satisfaction and cut costs, while you feel that satisfying customers inevitably increases costs. In this case, you are experiencing role conflict because satisfying one demand makes it unlikely to satisfy the other. Role overload is defined as having insufficient time and resources to complete a job. When an organization downsizes, the remaining employees will have to complete the tasks that were previously performed by the laid-off workers, which often leads to role overload. Like role ambiguity, both role conflict and role overload have been shown to hurt performance and lower job attitudes; however, research shows that role ambiguity is the strongest predictor of poor performance (Gilboa et al., 2008; Tubre & Collins, 2000). Research on new employees also shows that role ambiguity is a key aspect of their adjustment, and that when role ambiguity is high, new employees struggle to fit into the new organization (Bauer et al., 2007).

Information Overload

Messages reach us in countless ways every day. Some are societal advertisements that we may hear or see in the course of our day. Others are professional emails, memos, voice mails, and conversations from our colleagues. Others are personal messages and conversations from our loved ones and friends. Add these together, and it’s easy to see how we may be receiving more information than we can take in. This state of imbalance is known as information overload, which can be defined as “occurring when the information processing demands on an individual’s time to perform interactions and internal calculations exceed the supply or capacity of time available for such processing” (Schick, Gordon, & Haka, 1990).

Work–Family Conflict

Work–family conflict occurs when the demands from work and family are negatively affecting one another (Netemeyer, Boles, & McMurrian, 1996). Specifically, work and family demands on a person may be incompatible with each other, such that work interferes with family life and family demands interfere with work life. This stressor has steadily increased in prevalence, as work has become more demanding and technology has allowed employees to work from home and be connected to the job around the clock. Moreover, the fact that more households have dual-earning families in which both adults work means household and childcare duties are no longer the sole responsibility of a stay-at-home parent. This trend only compounds stress from the workplace by leading to the spillover of family responsibilities (such as a sick child or elderly parent) to work life. Research shows that individuals who have stress in one area of their life tend to have greater stress in other parts of their lives, which can create a situation of escalating stressors (Allen et al., 2000; Ford, Heinen, & Langkamer, 2007; Frone, Russell, & Cooper, 1992; Hammer, Bauer, & Grandey, 2003).

Work–family conflict has been shown to be related to lower job and life satisfaction. Interestingly, it seems that work–family conflict is slightly more problematic for women than men (Kossek & Ozeki, 1998). Organizations that are able to help their employees achieve greater work–life balance are seen as more attractive than those that do not (Barnett & Hall, 2001; Greenhaus & Powell, 2006). Organizations can help employees maintain work–life balance by using organizational practices such as flexibility in scheduling, as well as individual practices such as having supervisors who are supportive and considerate of employees’ family life (Thomas & Ganster, 1995).

Life Changes

Stress can result from positive and negative life changes. The Holmes-Rahe scale ascribes different stress values to life events ranging from the death of one’s spouse to receiving a ticket for a minor traffic violation. The values are based on incidences of illness and death in the 12 months after each event. On the Holmes-Rahe scale, the death of a spouse receives a stress rating of 100, getting married is seen as a midway stressful event, with a rating of 50, and losing one’s job is rated as 47. These numbers are relative values that allow us to understand the impact of different life events on our stress levels and their ability to impact our health and well-being (Fontana, 1989). Again, because stressors are cumulative, higher scores on the stress inventory mean you are more prone to suffering negative consequences of stress than someone with a lower score.

OB Toolbox: How Stressed Are You?

Read each of the events listed below. Give yourself the number of points next to any event that has occurred in your life in the last 2 years. There are no right or wrong answers. The aim is just to identify which of these events you have experienced.

Table: Sample Items: Life Events Stress Inventory

| Life event | Stress points | Life event | Stress points |

|---|---|---|---|

| Death of spouse | 100 | Foreclosure of a mortgage or a loan | 30 |

| Divorce | 73 | Change in responsibilities at work | 29 |

| Marital separation | 65 | Son or daughter leaving home | 29 |

| Jail term | 63 | Trouble with in-laws | 29 |

| Death of a close family member | 63 | Outstanding personal achievement | 28 |

| Personal injury or illness | 53 | Begin or end school | 26 |

| Marriage | 50 | Change in living location/condition | 25 |

| Fired or laid off at work | 47 | Trouble with the supervisor | 23 |

| Marital reconciliation | 45 | Change in work hours or conditions | 20 |

| Retirement | 45 | Change in schools | 20 |

| Pregnancy | 40 | Change in social activities | 18 |

| Change in financial state | 38 | Change in eating habits | 15 |

| Death of a close friend | 37 | Vacation | 13 |

| Change to a different line of work | 36 | Minor violations of the law | 11 |

Scoring:

- If you scored fewer than 150 stress points, you have a 30% chance of developing a stress-related illness in the near future.

- If you scored between 150 and 299 stress points, you have a 50% chance of developing a stress-related illness in the near future.

- If you scored over 300 stress points, you have an 80% chance of developing a stress-related illness in the near future.

The happy events in this list, such as getting married or an outstanding personal achievement, illustrate how eustress, or “good stress,” can also tax a body as much as the stressors that constitute the traditionally negative category of distress. (The prefix eu- in the word eustress means “good” or “well,” much like the eu- in euphoria.) Stressors can also occur in trends. For example, during 2007, nearly 1.3 million U.S. housing properties were subject to foreclosure activity, up 79% from 2006.

(Holmes, & Rahe, 1967).

“7.2: What Is Stress?” from Organizational Behavior by LibreTexts is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 International License, except where otherwise noted. Modifications. Some content removed. Added current stats.