20 Surviving off the Land

André-François Bourbeau and Manu Tranquard

Surviving off the land? A review of actual practices in Canada reveals that the teaching of wilderness survival is generally done in a haphazard manner, erroneously based on miscellaneous information deemed to be “cool” by outdoor enthusiasts in search of adventure. Unfortunately, this is far from an ideal approach to prepare for a real unexpected emergency for those who frequent remote outdoor environments for sports, work, or leisure.

In this article, the authors discuss the teaching of wilderness survival in order to meet the real needs of an outdoor emergency. The intent is to provide a best-practices outline to help survival instructors adapt their teaching accordingly, to go beyond the “surviving off the land” paradigm.

Introduction

Several previous studies have shown the importance of the outdoor adventure industry in Canada and the numbers of people who partake in outdoor related activities in remote environments for sports, work, or leisure (Tourisme Québec, 2007; KPMG, 2010; MELS, 2017; Tranquard, 2021a). Other studies have analyzed the amount of serious or fatal incidents which occur in Canada (Curran-Sills et al., 2013). The sheer numbers involved demonstrate the need for a systemic approach to prepare outdoor leaders and enthusiasts for potential life-threatening outdoor incidents.

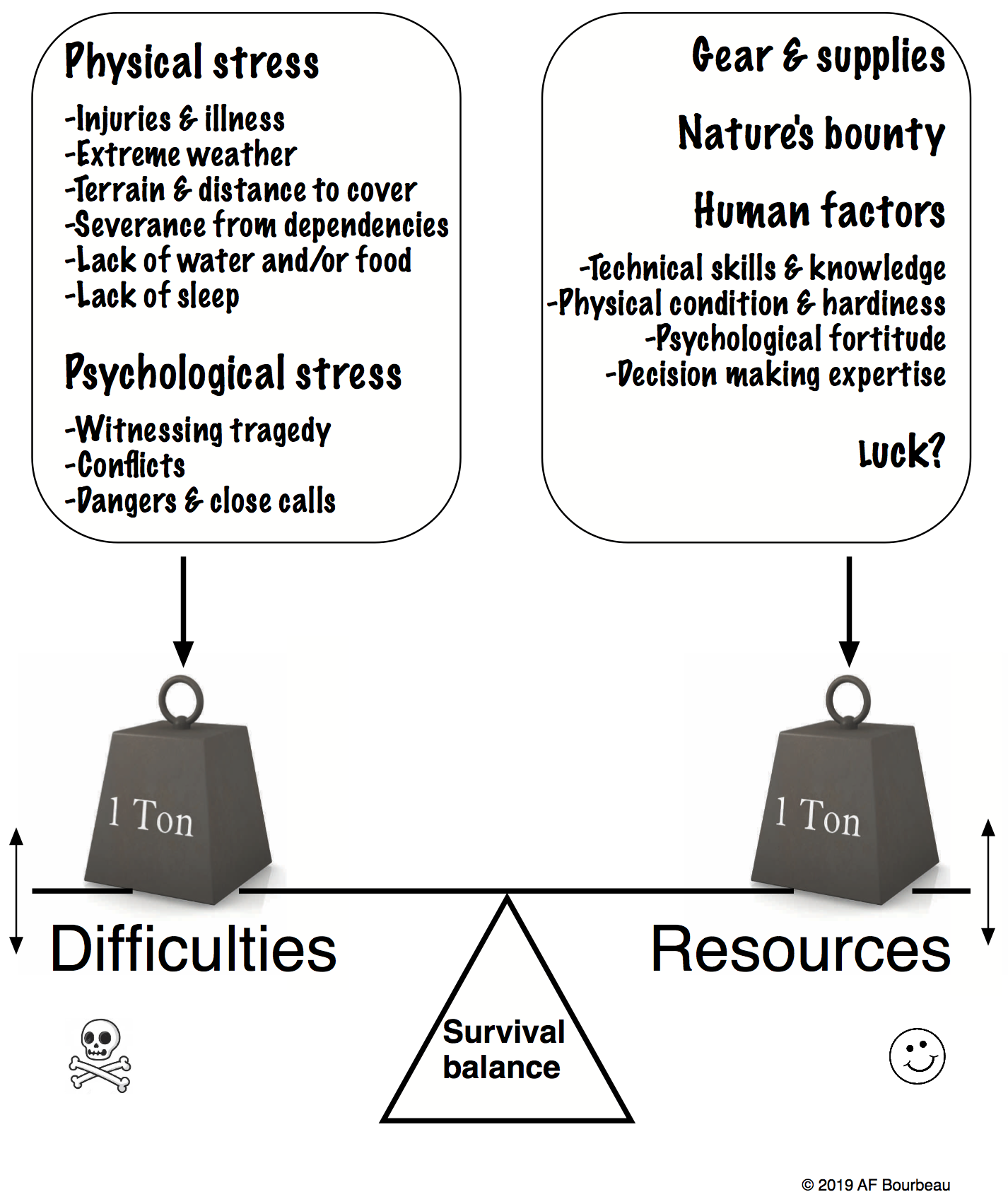

Bourbeau (2019) has argued that nothing can be changed in the outcome of a survival situation once it is upon you. Either you can deal with it and survive, or you can’t. In other words, you will face your predicament with the tools you are already in possession of: your actual physical fitness, psychological fortitude, decision-making capabilities, and outdoor skills. United States Army Survival Instructor Lutyens (2019) came up with a similar idea independently, called the survival balance, which weighs the difficulties of a given situation against the resources available to face them. Difficulties can be physical and/or psychological, whereas resources are measured as the sum of gear available, nature’s bounty, human factors, and perhaps luck, as shown in Figure 1.

This suggests that the primary goal of a wilderness survival teaching program should be to ensure that the balance can never fall on the wrong side. There are two ways to accomplish this: controlling the difficulties and gear available (risk management), or improving the strength of the human factors. Note that both of these approaches are preventive. Once in a predicament, it is too late, the survival balance then determines the outcome!

Risk management solutions

The purpose of risk management for the outdoors is therefore to verify ahead of time that during an outdoor activity, the difficulties encountered will not be greater than what the group can deal with while considering the gear and supplies they carry for the specific environment in which the trip evolves. In other words, it must be verified that the level of difficulty of a trip corresponds to the strength of the leaders and participants.

Quebec’s widely used risk management manual (AEQ, ACQ, LERPA, 2002) suggests a novel approach to ensuring this correspondence between trip difficulty and strength of group. In essence, outdoor activities are divided into four categories:

- Beginner (one hour from hospital, mostly day trips or overnight trips)

- Intermediate (one day from hospital, usually two to four day trips in semi-remote environments)

- Advanced (several days from hospital, any lengthy expeditions in remote environments where risks can usually be controlled)

- Expert (in very remote settings, while racing or attempting records, where risks are difficult to control, for example ocean crossings or climbing major peaks)

Once the difficulty of the trip is ascertained, safety becomes a matter of ensuring that the participants and leaders match the difficulty level, both in general outdoor competencies (camping), and also in the specific activity involved (canoeing). For participants in each category level, this means:

- Beginner (no experience necessary)

- Intermediate (several beginner experiences as background)

- Advanced (several intermediate experiences as background)

- Expert (several advanced experiences as background)

For leaders, this means having acted as leader several times in the previous category and having acted as assistant leader in the given category before acting as leader. The second most useful risk management tool (AEQ, ACQ, LERPA, 2002) is to file a trip plan which includes viable solutions for the following five pessimistic scenarios:

- Delay of 4 hours per day

- A participant is separated from the group

- The most important piece of gear is destroyed (usually means of transport or shelter)

- The leader becomes unconscious and needs emergency evacuation

- A participant needs evacuation for a non-life-threatening cause

Finding solutions to these scenarios obliges the leaders and participants of the trip to question the adequacy of their personal competencies, choice of gear, route selection, and the availability of “trip angels,” someone who can truly help if need be. These two major risk management tools, 1) ensuring match-up between trip difficulty and group competencies, as well as 2) filing an adequate trip plan, especially if validated by one or two other experienced outdoor leaders, will go a long way towards ensuring that the survival balance stays on the positive side.

In the opinion of the authors, the first concern of survival training should be to emphasize these two main risk management practices, including evaluating the participants’ strengths and weaknesses (Tranquard & Bourbeau, 2014). In this way, it will be less likely that individuals get in over their heads.

As previously stated, other than risk management, the only other way of positively affecting the survival balance in a preventive way is to use the survival program to improve the strength of the human factors, of which there are four (Bourbeau, 2019, Tranquard & Bourbeau, 2014):

- Technical outdoor skills and knowledge

- Physical condition and hardiness

- Psychological fortitude

- Decision-making expertise

Obviously, a short-term survival course cannot affect the survival balance all that much! Making a significant difference in any of the four factors is a long and ongoing process. The survival program should therefore endeavour to instill in the students the will to continue to improve in each of the four aspects, whilst at the same time, insisting on prevention through risk management. Since a wilderness emergency cannot be predicted, and the most dangerous aspect of a survival situation in Canada is to fend off cold, it is important to add “the habit of carrying a means of starting a fire in one’s pockets” and other such prevention habits to the risk management tools (to enhance availability of survival gear during an unexpected predicament). Let us now examine the most important course content for each of the four human factors which affect the survival balance.

Technical outdoor skills and knowledge

Most survival books and programs deal almost exclusively with this technical skills factor which deals with “surviving off the land,” the exciting part which attracts readers and students. Usually, there are sections on first aid, shelter, fire, water procurement, food sources (edible plants, hunting, trapping, fishing), protection from insects, signalling, orientation, and navigation (Angier, 2014; Bourbeau, 2011a; Brown, 1983; Davenport, 1998; Défense nationale, 1992; Fry, 1981; Olsen, 1997).

Learning the intricacies of all of these subjects can easily be a life-time endeavour! In a short survival program, the difficulty lies in choosing which of these subjects are the most important and merit a spot in the limited teaching and experimenting moments available. In the opinion of the authors, the elements which should be emphasized, those which are easy to learn and make the most difference to the real Canadian need in an unexpected emergency are confronting cold (Berry et al., 2008; Tipton, 2006) and facilitating rescue (Protecteur du citoyen, 2013). As for first aid, it should be suggested as a separate entity since instruction is commonly available. Note that food and water are included here because they help avert cold.

- How to start and maintain a fire and use it to stay warm with the use of a rear wall

- Bourbeau’s “Park bench” technique, a raised bed of poles to lie on

- The “Scarecrow” technique, which consists of stuffing clothing with dry material to improve insulation

- The importance of a makeshift hat

- The flat “Sponge roof” technique which absorbs rain vs the slanted “Shingles roof” technique which sheds rain

- The “Snow tomb” technique, a simple trench covered with evergreen branches and snow for fireless winter survival

- Frostbite prevention and quick solutions

- Bourbeau’s “Slush” technique, how to suck water from snow slush melted on a flat stick

- Drinking potentially bad water vs dehydration

- Common edible wild fruit (vaccinium, amelanchier), cattails (typha) and rock tripe (umbilicaria) as food

- Using green branches with fire for signalling

- Tracing an SOS inside a rectangle and/or using a V for signalling

Physical condition and hardiness

Although it is obvious that being fat and out-of-shape or otherwise physically disabled will make any survival ordeal that much more perilous, hardly any survival courses or documentation include these notions in their teachings. Nevertheless, the simple fact is that physical condition and hardiness are certainly at least as important to surviving a wilderness emergency as technical skills and knowledge. For example, when a snowmobile breaks down 30 km from help at minus 30 degrees, the marathon runner has a better chance of surviving than the very old and weak former boy scout, despite the latter’s skills.

The dilemma here is that physical fitness is perceived as an independent area of study, far removed from wilderness survival teaching priorities. Nevertheless, the authors suggest that, at the very least, physical fitness should be evaluated during a survival program in order to make students aware of their limitations, which encourages further risk management.

Also, the survival program should encourage further action by suggesting physical fitness and endurance training. Finally, it might be a good idea for survival programs, especially longer ones, to include increasingly physically demanding activities (like walking to another location) in order to kick-start the re-establishment of physical activities in the student’s lifestyle.

Psychological fortitude

The importance of psychological fortitude as a determining component of survival outcomes has been largely documented (Leach, 1994, 2004; Tranquard, 2017, 2021a). For example, motherly instinct is a powerful motivator, whereas a serious depression suggests the opposite. Unfortunately, survival literature rarely includes concrete ways of increasing such fortitude in students (Leach, 2022). The problem is compounded by ethics – it is not possible to torture students to teach them what it would be like to be tortured! The authors have spent substantial time considering this topic and have come up with the following ideas which can be safely included in survival curriculums (Bourbeau, 2011b, Tranquard & Bourbeau, 2014).

- Reading or relating facts concerning real survival ordeals and how people have reacted. Understanding how other individuals have lived through intense stress and suffering helps to mentally prepare for similar potential events.

- Participating in simulations in controlled situations with the possibility of immediate escape. This permits individuals to predict their reactions to a real threatening event.

- Suggesting voluntary solitary confinement or solitary trips in nature. This prepares for eventual solo survival ordeals.

- Suggesting resolving phobias or apprehensions or depression or addictions via professional psychological help.

- Participating in activities to improve group dynamics. Team building challenges, conflict resolution simulations, trust falls, group problem-solving, and so on, can be used to prepare for a group survival ordeal.

- Evaluating food aversions. It can be fun as well as instructive to evaluate the willingness of students to eat bizarre foods. For example, offer them a scoop of a mixture of chopped up bananas, chocolate, and baloney flavoured with molasses, mustard, and ketchup. Or have them drink juice stirred with a brand new fly swatter. This type of activity opens discussions relating to adaptation to new situations.

- Encouraging foreign travel. This too encourages adaptation and prepares psychologically for the acceptation of changes inherent during a survival ordeal.

- Completing survival challenges in a safe setting. The confidence gained by problem-solving while completing voluntary survival challenges is deemed helpful while confronting real challenges. 400 such challenges were created to help students develop outdoor skills at the University of Québec’s Outdoor Adventure Program (Bourbeau, 1996).

For example, these challenges vary from easy in level 1 (start a fire with a ferrocerium rod), through more difficult in level 2 (start a fire with paper matches but no striking surface), then advanced in level 3 (start a fire with an empty lighter), to extreme in level 4 (start a fire in the wilderness by using a piece of ice as a magnifying glass). Examples in other categories are

- Make a 2-meter rope from an old T-Shirt which will support your weight

- Make a basket out of natural materials, in which you can carry 1 kilo of rice with only one hand for 500 meters

- Peel 5 potatoes using a knife made by forging a 4-inch nail.

It was observed that solving these types of challenges over time not only helped with problem-solving skill development and dexterity, but also boosted psychological confidence and developed attitudes of prevention.

Decision-making expertise

The fourth human factor which seriously affects the survival balance is decision-making. Indeed, even if there are major strengths in the technical, physical, and psychological competencies, it is all too often bad decision-making which leads to trouble (Costermans, 2001; Flin et al., 1996; Klein et al., 2010; Schmidt & Lee, 2005). Most survival books offer priority based approaches to decision-making. In a similar way, many authors argue as to which task should be prioritized: first aid, fire, shelter, water? Or again, they provide lengthy arguments for and against staying put vs travelling to find a way out. But all too often, the answer is: “it depends!”

In the search for a better way to teach decision-making which is independent of context, the authors developed the SERA model (Bourbeau 2011a; 2013; 2019; 2022) which is based on the four actual “jobs” which need to be addressed while in a survival situation:

- S: Signal so search and rescue teams can find you or attempt self-rescue

- E: Energy needs to be conserved and when possible rejuvenated by water, food, and sleep.

- R: Risks must be avoided to prevent worsening of the situation

- A: Assets need to be cherished, they are precious

In essence, the SERA model consists of examining each and every decision in a survival context in light of its effect on the four SERA factors. In other words, to ascertain if you are improving your situation or making it worse, you always need to consider the effect of a decision on each of the four factors.

For example, suppose your snowmobile runs out of gas at -10 degrees Celsius and you are considering spending the night by building a Quinzee (snow shelter) with the emergency shovel you carry. Before doing so, you analyze this decision based on the 4 SERA factors:

- Signaling: from inside the soundproof shelter, you will no longer hear passing snowmobiles, and you might miss some rescue options (negative);

- Energy: you will expend quite a bit of energy building the shelter (negative), but it will be a few degrees warmer inside (positive);

- Risks: there is a moderate risk of spraining your back while shovelling and a slight risk of the snow collapsing on you (negative);

- Assets: your clothes are currently dry, but will be wet by the time you finish digging the snow house (negative).

The SERA model does not automatically imply that the right decision will always be taken, but at least the right considerations will have been made before executing a decision, which can be the difference between life and death.

Here again, the difficulty lies in finding efficient ways to teach students the decision-making process. One strategy the authors have experimented with is to ask students to show what they would do in the first thirty minutes if ever they were in a survival situation. They typically frantically proceed to gather firewood, make shelters, beds etc. At the end of the exercise, the sweaty students are asked if they would like to see what the instructors would do in the same situation. The instructors then simply pull out a whistle from their pockets, give it three blows, and all of a sudden, an assistant screeches in with an ATV vehicle and a case of beer. Lesson learned. Think SERA.

In the authors’ experience, decision-making is best learned by thinking through or finding solutions to invented scenarios, be they on paper or real-life. For example, if groups of three students are brought 3 km from home base in winter and 4 of their 6 boots are accidentally “burned” while drying them near the campfire, how can they get back to camp? Without the SERA model, they get an idea and immediately begin acting on it. But after thinking it through with the SERA factors in mind, they better see all of their options, starting with calling camp to see if someone can pick them up, sending one person for help with the two boots, saving energy while waiting for rescue, considering frostbitten feet, checking if they are willing to sacrifice gear assets to make emergency footwear, etc.

Summary

The outcome of a survival ordeal depends on the balance between the difficulties presented and the resources available to face them. The first option to maintain a positive balance is to implement two main risk management strategies. The first is to ensure that the level of difficulty of a trip is appropriate for the strength and experience of the group. Quebec’s risk management manual divides outdoor activities into four categories: beginner, intermediate, advanced, and expert. Participants should have a certain level of experience in the previous category before moving up to the next level. Leaders should have acted as leader in the previous category and as assistant leader in the current category before leading a trip. The second important risk management tool is filing a trip plan that includes solutions for five pessimistic scenarios: delay, participant separation, lost gear, unconscious leader, and participant evacuation.

The second option to positively impact the survival balance is to improve the four human factors of technical outdoor skills, physical condition, psychological fortitude, and decision-making expertise, but all of these are a long term process.

The two risk management tools suggested and improving the most quickly modifiable parts of each of the human factors should be the main focuses of a survival program.

Conclusion

Teaching new outdoor skills sometimes creates more of a security problem than it resolves. For example, a person who has never been down a rapid in a canoe will not likely attempt it. By teaching them simple basic strokes and taking them down some minor R-2 rapids just once, the fun they had might then incite them to try more difficult rapids which are beyond their capabilities. In this way, the fact that they took a beginner’s canoeing course has rendered them less safe, not safer. As outdoor leaders, we have to be particularly aware of this phenomenon.

In the wilderness survival world, we must be even more aware of the possibility that our teachings can give a false sense of security to our students. This is why best-practices must ensure that students maintain realistic views of their capabilities. It is not because you have learned to start a fire with a bow drill in a dry and controlled environment that you will be able to light one in a real survival setting with soggy wood during a downpour! And it certainly does not mean that you don’t need to carry a lighter or matches into the woods. It is essential to remember that the survival balance is independent of what has been taught; there will always exist the potential for a situation more dramatic than what the group can handle. The message must be loud and clear: forget about “surviving off the land” as anything other than an interesting pastime. Instead, focus on avoiding predicaments through prevention, prevention, and more prevention.

References

Angier, B. (2014). Comment survivre dans les bois: La référence absolue de l’aventure extrême. Hachette Aventure.

Aventure Écotourisme Québec (AEQ), Association des Camps du Québec (ACQ), Laboratoire d’Expertise et de Recherche en Plein Air (LERPA) (2002). Manuel de Référence pour la Gestion des Risques et de la Crise. Retrieved from https://aeq. aventure-ecotourisme.qc.ca

Berry, P., McBean, G., & Séguin, J. (2008). Vulnérabilités aux dangers naturels et aux conditions météorologiques extrêmes. Dans Santé et changement climatiques: Évaluation des vulnérabilités et de la capacité d’adaptation au Canada, Santé Canada.

Bourbeau, A.F. (1996). 400 Épreuves de coureur des bois. Notes de cours, 4SAP501 Activités traditionnelles, Université du Québec à Chicoutimi.

Bourbeau, A.F. (2011a). Le Surviethon- Vingt-cinq ans plus tard. Les Éditions JCL.

Bourbeau, A.F. (2011b). Développement de l’expertise en survie. Retrieved from http://lerpa.uqac.ca/pdf/expertise_survie.pdf

Bourbeau, A.F. (2013). Wilderness Secrets Revealed. Dundurn Press.

Bourbeau, A.F. (2019). Decision-making model for wilderness survival. Global Bushcraft Symposium Keynote Conference, Foothills Center, Bowden, Alberta. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HiKckM85g6s

Brown, Jr., T. (1983). Tom Brown’s field guide to wilderness survival. Berkley Publishing, 282.

Costermans; J., (2001). Les activités cognitives: raisonnement, décision et résolution de problèmes, Bruxelles, Editions De Boeck Université, 2ème ed., Neurosciences & Cognition.

Curran-Sills G., McDonald, N., Pauerba. P.S. & Crutcher, R. (2013). Embracing the wild: Conceptualizing wilderness medicine in Canada. Canadian Family Physician, 59, 581-584.

Davenport, G. (1998). Wilderness Survival. Stackpole books.

Défense nationale. (1992). Manuel B-GL-382-006/FP-001: Survie (adaptation par les Forces canadiennes du document US Field Manual 21-76).

Flin, R., Slaven, G., & Stewart, K. (1996). Emergency decision making in the offshore oil and gas industry. Human Factors, 38, 262-277.

Fry, A., 1981. Survival in the wilderness—A practical, all-season guide to traditional techniques for hikers, skiers, backpackers, canoeists, travelers in light aircraft, and anyone stranded in the bush. Macmillan of Canada.

Klein, G., Calderwood, R., & Clinton-Cirocco, A. (2010). Rapid decision making on the fire ground: The original study plus a postscript. Journal Of Cognitive Engineering And Decision Making, 4(3), 186-209.

KPMG Services Conseils (2010). Diagnostic – Tourisme nature, Québec, 39.

Leach, J. (1994). Survival psychology. Palgrave Macmillan

Leach, J. (2004). Why people ‘freeze’ in an emergency: Temporal and cognitive constraints on survival responses. Aviation, Space & Environmental Medicine, 75, 539–542.

Leach, J. (2022). Personal communication. Global Bushcraft Symposium, Snowdonia National Park, North Wales, United Kingdom.

Lutyens, T. (2019). Personal communication. Global Bushcraft Symposium, Foothills Center, Bowden, Alberta.

MELS – Ministère de l’Éducation, du Loisir et du Sport. (2017). Avis sur le plein air: Au Québec, on bouge en plein air!

Olsen, L.D. (1997). Outdoor survival skills – 6th Ed. Chicago Review Press.

Protecteur du citoyen, (2013), L’organisation des services d’intervention d’urgence hors du réseau routier: une desserte à optimiser pour sauver des vies, Québec.

Schmidt, R. A. & Lee, T. D. (2005). Motor Control and Learning: A Behavioral Emphasis. Human Kinetics.

Tipton, M. (2006). Human physiology and the thermal environment et Thermal stress and survival In D. Rainford & D. Gradwell (Eds.) Ernsting’s aviation medicine (pp. 189-229), Arnold.

Tourisme Québec. (2007). Le Québec Grande nature – Plan intégré de l’expérience: Diagnostic et orientations, Québec, 24.

Tranquard, M. (2017). La pratique de la recherche scientifique concernant la survie en forêt: principes, méthodes, outils et exemples récents. ACFAS, Université McGill.

Tranquard, M. (2021a). L’intervention plein air au Québec: considérations géographiques, techniques, culturelles et socio-historiques. Nature & Récréation, 10, 28-48.

Tranquard, M., (2021b), Activités professionnelles en milieu naturel au Québec: l’enjeu de la formation en survie en région isolée. In J-M. Adjizian, D. Auger, & R. Roult (Eds.), Plein air: Manuel réflexif et pratique (pp. 131-148), UQTR, Hermann Éditeurs.

Tranquard, M. (2022), La survie en forêt comme champ de recherche scientifique: cadre théorique, méthode d’analyse et résultats récents. Annales des Mines – Responsabilité et environnement, soumis.

Tranquard, M. & Bourbeau, A-F. (2014). Gestion des risques en tourisme d’aventure: proposition d’un outil d’évaluation du potentiel de survie en forêt. Téoros, 33(1), 99-108.