21 Professional Obligations for Risk and Safety

Jeff Jackson

Leaders Creating and Controlling Risk

The outdoor leader has a difficult job. Despite the beautiful places, enjoyable activities, and often wonderful companions, the job also entails hard physical work, long hours, time away, and dealing with all types of weather and people. Beyond that, though, adventure – as the purposeful pursuit of risk – makes adventure guiding a very ambiguous position when it comes to managing risk.

Leaders take their clients into dangerous locations and then protect them when they get there. Leaders are the creators and controllers of risk. They both produce risk and protect against it. This is a highly subjective situation to be in, especially when asked to defend how much risk is enough? The very nature of adventure activities involves subjective decisions regarding how much risk exposure is suitable for a given group, and how much and what kind of safety precautions to apply. This balance between producing risk and protecting from risk will often be viewed unfavourably against the leader when something goes wrong. Why did they allow so much exposure? Why did they not apply more effective safety measures? Because of this ambiguity, there are defined professional obligations when it comes to planning and managing for risk and safety.

For the purposes of this chapter, adventure is defined as the purposeful pursuit of risk. This limits the scope of this piece, as only a narrow slice of outdoor and experiential learning specifically seeks risk as fundamental to their purpose or program. For the wider outdoor learning, outdoor recreation, or experiential education sector, risk may be perceived as negative, and is to be reduced at all levels (Jackson, et al., 2023). In other domains such as adventure tourism, adventure recreation, or adventure education, challenge and risk are essential to realize the desired outcomes.

Risk and Uncertainty

Problematic in this discussion is the root word “risk.” Mainstream interpretation of this word would equate to something similar to “the potential for loss.” This is not without argument, as there are dozens of formal definitions in print, and the word itself traces its history back to Ancient Greek. What is missing from the mainstream interpretation is the flip side of the word; the potential for gain. For fields such as adventure activities, this positive aspect is particularly important to balance the potential for loss against the potential for gain. Rather than wade into this philosophic and semantic debate, this chapter will simply consider risk as uncertainty, without judgment as to positive or negative consequences.

The economist Frank Knight differentiated between risk and uncertainty in his landmark book Risk, Uncertainty, and Profit (1921). Risk can be quantified absolutely with probability, he argued, while uncertainty has no calculable probability (Knight, 1921, I.I.26).

Uncertainty must be taken in a sense radically distinct from the familiar notion of “risk,” from which it has never been properly separated… It will appear that a measurable uncertainty, or “risk” proper, as we shall use the term, is so far different from an unmeasurable one that it is not in effect an uncertainty at all. We shall accordingly restrict the term “uncertainty” to cases of the non-quantitative type.

The adventure guiding, recreation, and education field deals almost exclusively with uncertainty, as the risks, hazards, and potential for loss are overwhelmingly of the non-quantitative type.

Further, this chapter will refer to the adventure ‘leader,’ which includes guides, instructors, teachers, or any other lead role that has a professional obligation to plan and manage risk and the safety of a group.

A secondary assumption for this discussion is that the adventure leader is operating under an organizational umbrella, whether it be a guide service, outfitter, or educational institution. This implies, then, that there are organizational and system influences that interact with the decisions and actions of the leader.

This balance between the ‘right’ amount of risk and the ‘right’ amount of safety becomes the focal point of lawsuits. When asking if the leader performed to an expected standard, implied is the risk present versus the safety applied. One judge in a heli-ski case (Scurfield v. Cariboo Helicopter Skiing Ltd., 1993) explained:

It is not contended that the defendants [i.e. the guides] had a duty to ensure that their guests were kept away from all places where avalanches could occur ─ in the context of helicopter skiing that would be impossible. I think it is correct to say that the duty of care which lay on the defendants was not to expose their guests to risks regarded in the business as unreasonably high, whether from avalanche or any other hazard to which participants in the sport are normally exposed. To enjoy the excitement of skiing in mountain wilderness areas, participants are necessarily exposed both to risks which the careful skier is able to avoid and certain risks also which such skiers may be unable to avoid, including some risk of being caught in an inescapable avalanche.

The tension between creating and controlling risk is a core element of professionally facilitated adventure activities. As such, there are specific professional expectations when it comes to managing risk and safety. These expectations are formed from three sources:

- Peer practice, or an estimated ‘industry standard’ – performing similarly as others would in a similar context, with similar training and client groups.

- Court rulings and judicial opinion – court decisions serve to measure a particular circumstance against specified law or societal expectations.

- Social license – moral or societal expectations that create performance requirements in order to be deemed ‘acceptable,’ or to direct towards the ‘right thing to do.’

Leaders’ Professional Obligations

At a base level, these professional obligations include supervision, care, prudence, risk assessment, safety briefings, and doing the right thing.

First and foremost, the leader supervises. The leader is in charge of the group and the scenario, and it is expected that whatever goes on within that context does so under the eye of or the direction of the leader. As evidence, ‘failure to supervise’ shows up in many related adventure guiding lawsuits (i.e. Stations de la vallée de St-Sauveur Inc. c. M.A., 2010).

Secondly, leaders take care of people. Within the parameters of the activity, trip or environment, the leader’s job is to look out for their clients. In Canada, the leader is more than the one who knows the way; theirs is a greater role that is concerned with the care of people (Jackson & Heshka, 2021).

Third, the leader is expected to perform as other leaders would in that situation. This is the ‘reasonable instructor’ test or ‘reasonable guide’ test discussed in legal liability settings (Ochoa v. Canadian Mountain Holidays Inc., 1995, Roumanis v. Mt. Washington Ski Resort Ltd., 1995). A leader needs to know the typical and expected behaviours that would be endorsed by their peers, and reliably perform to those. To go beyond or outside what most leaders would consider ‘normal’ would require exceptional circumstances, and expose one to claims of failing in their duty as a leader.

Fourth, leaders assess risk and plan for emergencies. Dynamic risk assessment is a continual in-field process, and risk assessment as a planning tool happens every trip and as a part of pre-trip staff briefings. Leaders grow to see the world through a risk assessment lens and are expected to apply suitable safety measures when they sense emergent hazards or escalating risk levels. In the event of a non-normal occurrence, an injury, or some other emergency, it is expected that the leader will have an emergency response plan sufficient to assist with such an event (Isildar v. Rideau Diving Supply, 2008).

Fifth is safety briefings. Leaders are expected to inform their participants of the expected hazards and outline the expectations on the client to assume and manage some aspects of their own safety (Isildar v. Rideau Diving Supply, 2008). Transport Canada Regulations (SOR/2010-91) specify that all ‘guided excursions’ on water are required to include a pre-trip safety briefing, the logic of which can reasonably be extended to all led outdoor activities regardless of domain. This risk communication can extend to pre-trip information or parental consent briefings. It can be argued that modern adventure-based risk management is organized around this communication exchange before and during facilitated activities (Jackson & Heshka, 2021).

Sixth, and lastly, the leader understands that in some aspects their role is defined and prescribed by their supervisor, and in others it is up to the individual leader to do the right thing. The author Robert Kegan called this as being at the same time a “hired hand and master of one’s fate” (1994, p.1). Large aspects of the adventure leader’s role is unsupervised. The leader is on their own to steer the boat, direct their group, or set up a site. No one is looking over their shoulder to ensure they are doing it right. Within those acts, the leader’s organization may prescribe what lines to take down a rapid, what trails are suitable and which are not, and what a suitable site setup looks like. There are myriad opportunities for the leader to take shortcuts or skimp on safety – the odds are it will likely work out okay – but routines are in place to ensure consistent, quality programs that fall within prescribed risk tolerance guidelines. The leader’s role is to perform to these invisible lines, even when no one else is looking. When the rules aren’t clear or a situation emerges that is not covered by normal routines, it is up to the guide to assess the risk, consider the options, and conservatively implement the best option.

Risk Tolerance, the Organization and Leaders

The term “risk tolerance” was introduced to the outdoor sector in the Cloutier (2003) report on the Connaught Creek avalanche, and is defined as the articulated limits on the nature and magnitude of dangers to which an organization will expose its clients, staff, and self (Jackson & Heshka, 2021).

In his book Target Risk (1994), Gerald Wilde explained that all individuals have a desired level of risk in their life ─ some position on the spectrum between absolute safety and absolute danger ─ that they accept, and in fact seek it. He called this “risk homeostasis,” and it helps explain why some climbers expose themselves to avalanches and rock falls, for example, while other equally skilled climbers shy away from such terrain – individuals choose the level of risk they are willing to expose themselves to. In other words, this is pointing toward an individual’s decision-making, risk tolerance, and internal balance between risk and reward.

Risk tolerance has a different tone and gravity when applied to organizations, educational institutions, or commercial guiding operations. When considered in the context of a leader’s duty of care, decisions and tolerance for risk by the leader now directly affect those they are charged with caring for. Every organization has a certain risk tolerance, present in every single decision that is made. If not articulated expressly, then it is buried deeply in the assumptions that underlie the organization’s mission, values, and history. These base-level assumptions may or may not be universally shared throughout the organization (Jackson, 2016).

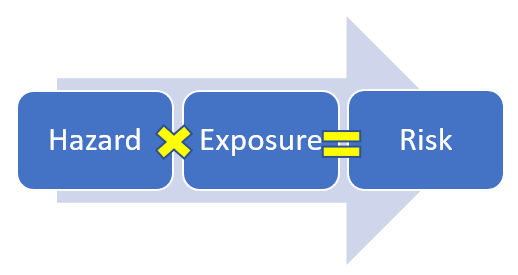

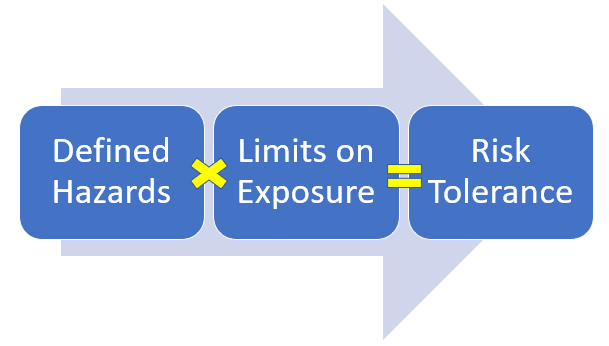

One of the basic models for organizing and understanding risk, shown in Figure 1, proposes that risk is a function of hazards and the exposure allowed to that hazard. If this is so, then it can be the basis for understanding risk tolerance, shown in Figure 2, as a function of defined hazards and the limit on exposure to those hazards.

Inherent in the idea of risk tolerance is choice. An organization is not at the mercy of the environment in which it finds itself – it must choose where it will position itself, choose what strategic direction it will and will not go, choose the hazards it deems beneficial to confront, and choose the terms on which it will expose its clients, staff, and self to particular uncertainty. This can be applied to trip types, program locations, client groups, operational uncertainty, and strategic decisions. Risk tolerance gives an organization’s decision-makers the ability to act, and makes no assumptions about what must or must not happen. Decisions made at this organizational level directly set up adventure leaders and the risk baked into the activities they run on behalf of the organization.

Organizational risk tolerance has substantial ethical implications. Normal accident theory, proposed by Charles Perrow (1999), directly addressed this issue, and argued that risk tolerance is not about corporate culture – those articulated or embedded assumptions – but about power. Risk tolerance is about who gets to decide. Who gets to decide what hazards a program will willingly confront? Who gets to decide the exposure level? Rarely is it the clients. Often, even the leaders don’t get to decide. Adventure tourism in particular is implicitly based on a caveat emptor/buyer beware risk philosophy. Clients deciding on an adventure vacation rarely have the understanding to fully assume the hazards and exposure level an operator has embedded in their trips or activities. Taken to children, schools, and adventure education, the ethical implication grows, and opens a liability can of worms. The organization has the obligation to plan suitable programs and trips with hazards that are within the ability of the leader to manage.

For the leader, organizational risk tolerance can provide clear direction – if that risk tolerance is clearly defined and uniformly applied throughout the organization. This clarity could be found in the form of specific cut-off levels or times, weather warning cancellations, or base-level staffing requirements. If these ‘rules’ are not clear or unevenly applied, interpreting risk tolerance adds a layer of ambiguity to the professional leader’s role. Cognitive effort is required to intuit the numerous indirect cues offered by the organization or by the manager in order to estimate the accepted level of risk. From the manager’s standpoint, and from a systems planning perspective, articulating risk tolerance is the first step in building effective risk management and safety systems.

Risk Planning Obligations

Risk management is about planning ─ the absolute fundamental building block number one of safety-oriented adventure trips, activities, and facilities. Leaders planning for safety, for their trip, their day, and their clients’ experience they will create; managers planning their systems, routines, training, risk assessment, and documentation; the organization planning for sustainability and operating within a specified risk tolerance. This is the ‘blunt’ end of adventure – all the things that go on before a trip ever starts, yet set it up for success.

Safety is individual decisions and actions that limit exposure to any one hazard or risk. For adventure trips, this is the leader’s job. Safety is a front-line activity, assessed and managed on a moment-by-moment basis. Safety, as limiting exposure, is found everywhere in adventure: ensuring clients have their life jackets buckled up; checking the battery on the cell phone before the trip leaves; double-checking anchor knots; moving out of the way of oncoming traffic; mopping up spilled water at an entryway; positioning clients in the proper location while the leader prepares equipment – all day, every day, safety is created by frontline leaders.

Risk management is the systems that are in place to ensure that hazards are minimized, safety is consistently practised, and overall exposure to risk is controlled to levels acceptable to the organization. Risk management is the manager’s job. What we know is that the organizational structures, systems and routines that are in place set the stage for front line workers to do their job effectively (Rasmussen, 1997). Poor planning or poor systems set up employees for poor performance. Poor performance opens the door to unsafe conditions.

Within the organization, analysis of Canadian-led outdoor activity fatalities pointed to several key factors that persist over time (Jackson et al., 2023). Key person dependency, where one person is responsible for risk decisions and program delivery, was found as a common thread, and in the cases reviewed, was combined with a lack of supervision oversight. One individual was running a high-risk program in a vacuum. Overlapping factors of unclear organizational risk tolerance and signs of risk creep were also evident. Risk creep refers to the incremental and unnoticeable increases in risk as programs progress and as staff become comfortable with old risks (Jackson & Heshka, 2021). With these conditions persistent over time, the organization’s risk planning obligation is to account for and mitigate these known risk factors in advance.

Adventure Activities as Complex Social Systems

Some significant disasters in the adventure sector forced practitioners to re-think risk management as more than field-level safety decisions. Adventure researchers in Australia looked to industrial safety theory and offered a significant step forward in risk planning (Carden, Goode, Salmon, 2017). An earlier industrial safety researcher, Jens Rasmussen, envisioned safety as more than the ‘operator’ on the shop floor. In his landmark paper (1997), he theorized that risk management involved several layers of influence: government regulations and laws influence industry regulations; those industry regulations influence organization or company structure, goals, policy and practices; those company goals influence the manager and their directions to staff; staff take their cues from all of the above and incorporate those as variables into their own decision-making and safety actions.

In effect, the adventure leader is on the downstream end of many influences. It is disingenuous to automatically blame the leader when something goes wrong, when in fact the error may have been handed to them from some other higher layer of risk management planning or subtle social influence. Accident theorist James Reason believed that human error is a consequence, and not a cause. Individuals perform to their ability, and (mostly always) believe they are doing the right thing or the best they can (Reason, 2016). The conditions under which guides work may have set them up for failure: impossible time restrictions, difficult conditions (i.e. sending out a group with impending severe weather), assistant guides that are more liability than help, clients with individual needs beyond the ability of the guide; the list can be long. While the highest levels of ‘the system’ are beyond the influence of the leader and (likely) the organization, there is an obligation to recognize the latent errors that existing regulations, lack of regulation, industry practice, and other stakeholders such as certification bodies play in influencing program layout and leader safety decisions in the field.

Conclusion

The outdoor leader is expected to create risk and then control for it. This ambiguous position is open to wide subjective interpretation and has inputs by the individual leader, the supervisor, at the organizational level, and system influences beyond the organization. Peer practice, societal expectations, and court decisions all direct adventure leaders in defining their professional obligations with regard to managing risk and safety. Beyond the leader, there are expectations upon the organization to define its risk tolerance and plan suitable adventure activities that only incorporate those hazards that are manageable by the leader.

References

Carden, T., Goode, N., & Salmon, P. M. (2017). Not as simple as it looks: Led outdoor activities are complex sociotechnical systems. Theoretical Issues in Ergonomics Science, 18(4), 318–337. https://doi.org/10.1080/1463922X.2017.1278806

Cloutier, R. & Bhudak Consultants Ltd. (2003). Review of the Strathcona-Tweedsmuir School outdoor education program. https://www.acmg.ca/pdf/Strathcona%20Tweedsmuir%20School%20Outdoor%20Ed%20Program%20Review.pdf

Isildar v. Rideau Diving Supply, 2008 CanLII 29598 (ON SC). https://canlii.ca/t/1xmgh

Jackson, J., & Heshka, J. (2020). Managing risk: Systems planning for outdoor adventure programs (2nd ed.). Algonquin Thompson Publishing.

Jackson, J., Priest, S., & Ritchie, S. (2023). Outdoor education fatalities in Canada: A comparative case study. Canadian Journal of Educational Administration and Policy, 202, 141–154. https://doi.org/10.7202/1099988ar

Jackson, J. S. (2016). Beyond decision making for outdoor leaders: Expanding the safety behaviour research agenda. Journal of Outdoor Recreation, Education, and Leadership, 8(2), 103–118. https://doi.org/10.18666/JOREL-2016-V8-I2-7692

Kegan, R. (1997). In over our heads: The mental demands of modern life. Harvard University Press.

Knight, F. H. (1921). Risk, uncertainty and profit. Houghton Mifflin.

Ochoa v. Canadian Mountain Holidays Inc., 1995 CanLII 1360 (BC SC). https://canlii.ca/t/1dqk9

Perrow, C. (1999). Normal accidents: Living with high-risk technologies. Princeton University Press.

Rasmussen, J. (1997). Risk management in a dynamic society: A modelling problem. Safety Science, 27(2–3), 183–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0925-7535(97)00052-0

Reason, J. (2016). Managing the risks of organizational accidents (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315543543

Roumanis v. Mt. Washington Ski Resort Ltd., 1995 CanLII 763 (BC SC). https://canlii.ca/t/1dq6d

Scurfield v. Cariboo Helicopter Skiing Ltd., 1993 CanLII 2007 (BC CA). https://canlii.ca/t/1dbl1

Stations de la vallée de St-Sauveur inc. C. M.A., 2010 QCCA 1509 (CanLII). https://canlii.ca/t/2c6sf

Small Vessel Regulations (2023), SOR/2010-91. https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/regulations/SOR-2010-91/index.html