2 Introduction: What Is Outdoor Learning?

Simon Priest

Authors’ note: Spirituality in this chapter refers to comprehending our place in the world–our search for satisfaction or serenity, why we were put here, and what role we were meant to play with others and nature–during our brief time on the planet, with or without religion or transcendence.

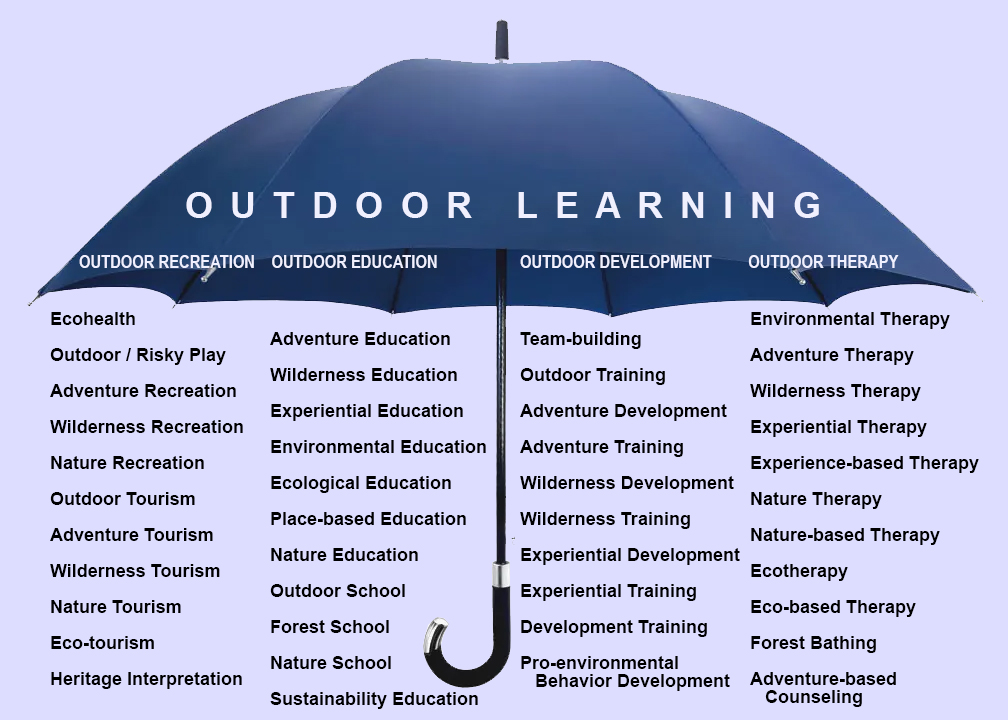

The umbrella term of outdoor learning has been difficult to define due to the wide variety of programs that exist, thrive, and survive under its cover. Figure 1 lists just a few of its synonymous labels. One of the earliest recent definitions came from England: “Outdoor Learning is a broad term that includes: outdoor play in the early years, school grounds projects, environmental education, recreational and adventure activities, personal and social development programmes, expeditions, team building, leadership training, management development, education for sustainability, adventure therapy … and more” (English Outdoor Council, 2018; Greenaway, 2005).

Another British organization, unfortunately, used the words “learning” and “outdoors” to define outdoor learning as “actively inclusive facilitated approaches that predominately use activities and experiences in the outdoors which lead to learning, increased health and wellbeing, and environmental awareness” (Institute for Outdoor Learning, 2021). They later substituted “nature” for “the outdoors” and “change” for “learning.” However, the learning leads to more than just wellness and environmental outcomes.

The National Curriculum of Australia (2020) states that “the development of positive relationships with others and with the environment through interaction with the natural world … are essential for the wellbeing and sustainability of individuals, society and our environment. Outdoor learning engages students in practical and active learning experiences in natural environments and settings, and this typically takes place beyond the school classroom. In these environments, students develop the skills and understandings to move safely and competently while valuing a positive relationship with natural environments and promoting the sustainable use of these environments.”

In the United States, Americans use the term “experiential education” to emphasize the learning methods and innovative teaching/facilitating used extensively with participants in the outdoors. “Experiential education is a teaching philosophy that informs many methodologies in which educators purposefully engage with learners in direct experience and focused reflection in order to increase knowledge, develop skills, clarify values, and develop people’s capacity to contribute to their communities” (Association for Experiential Education, n.d.).

Definitions from the nations above share some common content: experiential, relationships, and nature or natural environments. In this book, the umbrella term of Canadian outdoor learning is defined using these commonalities as “an experiential process … which takes place primarily through exposure to the out-of-doors [where] the emphasis for the subject of learning is placed on … [five] relationships concerning people and natural resources” (Priest, 1986, p. 13). Those five relationships include:

- Intrapersonal – participant relating to oneself (self-esteem, resilience, confidence, etc.);

- Interpersonal – participant relating to others (prosocial skills, trust, communication, etc.);

- Ecosystemic – elements of nature interacting with each other (food chains, web of life, etc.);

- Ekistic – humans and nature interacting reciprocally (pollution of drinking water, etc.); &

- Spiritual – a participant understanding their place or role in the world (Priest & Gass, 2018).

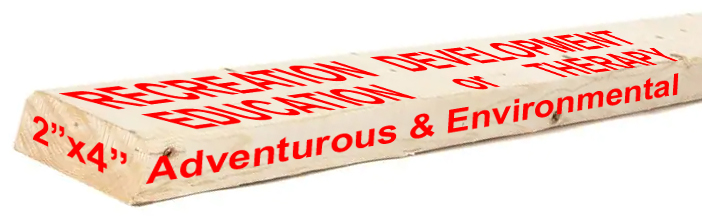

Outdoor learning involves teaching with a two-by-four: two branches of activities and four types of programs. Truly effective outdoor learning utilizes both branches of activities within each of the four program types to teach about and bring about much-needed change associated with all five relationships. In fact, practitioners may have great difficulty having an impact on spiritual relationships without first successfully addressing the other four. Participants who know themselves and how to work with others and who know an ecosystem and how they affect it and how it affects them can decide how they best fit in.

Outdoor learning has two activity sides: adventurous and environmental. Adventurous activities range from games and group problem-solving initiatives, to low and high ropes/challenge courses, to one-day excursions or multi-day expeditions (snowshoeing, skiing, bicycling, hiking, climbing, caving, canoeing, kayaking, sailing, and more). Environmental activities range from sensory immersion in nature, to mindful meditation or contemplation, to scientific or artistic ecological exercises conducted outdoors in natural surroundings (Canadian Outdoor Therapy and Healthcare, n.d.).

Outdoor learning comes in four program types depending on what the lesson is meant to change: feeling, thinking, behaving, or resisting efforts to create positive change as shown in Table 1 below. Outdoor recreation (including tourism) changes the way participants feel through fun, play, enjoyment, and the learning of new activity skills. Outdoor education changes the way participants think by gaining new concepts, reinforcing old ones, and creating an awareness of the need to change behaviours. Outdoor development changes the way participants behave by enhancing positive actions and increasing their functioning. Outdoor therapy changes the way participants resist efforts to transform them positively by reducing negative or maladaptive behaviours in order to ease their dysfunction (Priest, 2021).

|

OUTDOOR… |

RECREATION |

EDUCATION |

DEVELOPMENT |

THERAPY |

|

Intends to change |

Feeling |

Thinking |

Behaving |

Resisting Change |

|

Subject matter or learning focused on |

Having fun, playing, enjoying, learning new activity skills |

Gaining new and old concepts or awareness of need to make changes |

Enhancing positive conduct or actions (grow functioning) |

Reducing negative conduct or actions (ease dysfunction) |

For example, adventurous activities range from guided mountain climbing or sailing with tourists, to schoolyard socialization games and corporate team-building events, to a wilderness expedition for youth with substance abuse or criminal histories. Similarly, the use of environmental activities can progress from ecological interpretation or wildlife identification with a naturalist, through high school sustainability awareness exercises and pro-environmental action inculcated by teachers, to treating stress, anxiety or depression in adults via immersion into natural greenspace with a therapist.

This chapter has provided a very brief introduction to outdoor learning. The following chapters present an overview of outdoor learning in Canada. Subsequent chapters will address various topics that practitioners may find helpful in their outdoor learning work with Canadian participants. Each chapter will define terms as these arise, but in this chapter Canadian outdoor learning is an experiential process that takes place primarily through exposure to nature and the outdoors, where the emphasis is on one or more relationships concerning people and nature.

Adventurous learning develops intrapersonal and interpersonal relationships, while environmental learning develops ecosystems and ekistic relationships. Employed together, these two outdoor learning approaches can develop spiritual relationships. Improving these five relationships can help participants change the way they feel, think, behave, and/or resist positive efforts to change (Priest & Gass, 2018).

Future Directions

This historic definition puts outdoor learning in a nice box that satisfies the policy and procedure makers of our society. However, in the future, we must think outside that box. In many ways Canada is behind other developed nations when examining state-of-the-art practices for outdoor learning, but we do have an advantage in our efforts toward truth and reconciliation with Indigenous Canadians and toward partnerships with nature for change. In a solution-focused manner, we must do more of what is starting to work for us.

While honouring our past work, outdoor learning in Canada is ready for a revolution of new ideas. The ignition for some of those new ideas can be found herein with chapters on indigeneity, decolonization, ecohealth, climate collapse, nature reciprocity, trauma-informed care, racial imbalances, temporary able-bodiedness, and different ways of thinking and acting.

With the plethora of problems related to the Earth’s systems as the result of previous ways of thinking and acting, what we must also begin to “do more of” is include expert voices from all genders, ethnicities, indigeneities, and orientations. Canada is a diverse pluralistic society and outdoor learning must include all of those elements. To this end, we invite and welcome additional contributions to this living textbook and especially gifts from authors who are not simply defined by an older white cis-male identity.

References

Association for Experiential Education. (2024). What is experiential education. https://www.aee.org/what-is-experiential-education

Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority. (2020). Outdoor learning. Australian Curriculum. https://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/resources/curriculum-connections/portfolios/outdoor-learning/

Canadian Outdoor Therapy & Healthcare. (n.d.). Best practices: Activities. Canadian Outdoor Therapy & Healthcare. Retrieved February 11, 2024, from http://coth.ca/prac.html#ACT

English Outdoor Council. (2018). What is outdoor learning? https://www.englishoutdoorcouncil.org/outdoor-learning/what-is-outdoor-learning

Greenaway, R. (2005). What is outdoor learning. https://web.archive.org/web/20231003040318/https://www.outdoor-learning-research.org/Research/What-is-Outdoor-Learning

Institute for Outdoor Learning. (2021). Outdoor learning. https://www.outdoor-learning.org/Portals/0/IOL%20Documents/About%20Outdoor%20Learning/RR1%20-%20Describing%20Outdoor%20Learning%202-8-21.pdf?ver=2021-08-10-133755-690

Priest, S. (1986). Redefining outdoor education: A matter of many relationships. The Journal of Environmental Education, 17(3), 13–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/00958964.1986.9941413

Priest, S. (2021). Adventure therapy in Canada. Academia Letters. https://doi.org/10.20935/AL3831

Priest, S., & Gass, M. A. (2018). Effective leadership in adventure programming (Third Edition). Human Kinetics.